The normalisation of Stage 6 load shedding during the first quarter of 2023 has reinforced a society-wide, bottom-up response to the energy crisis. For those with statist predilections, this is their worst nightmare come true – a market-driven disorderly energy transition.

On the extreme end of this view, this bottom-up energy transition is tantamount to politico-economic Armageddon. For others, it is confirmation that once again the virtues of the market have saved us from a state-induced economic collapse.

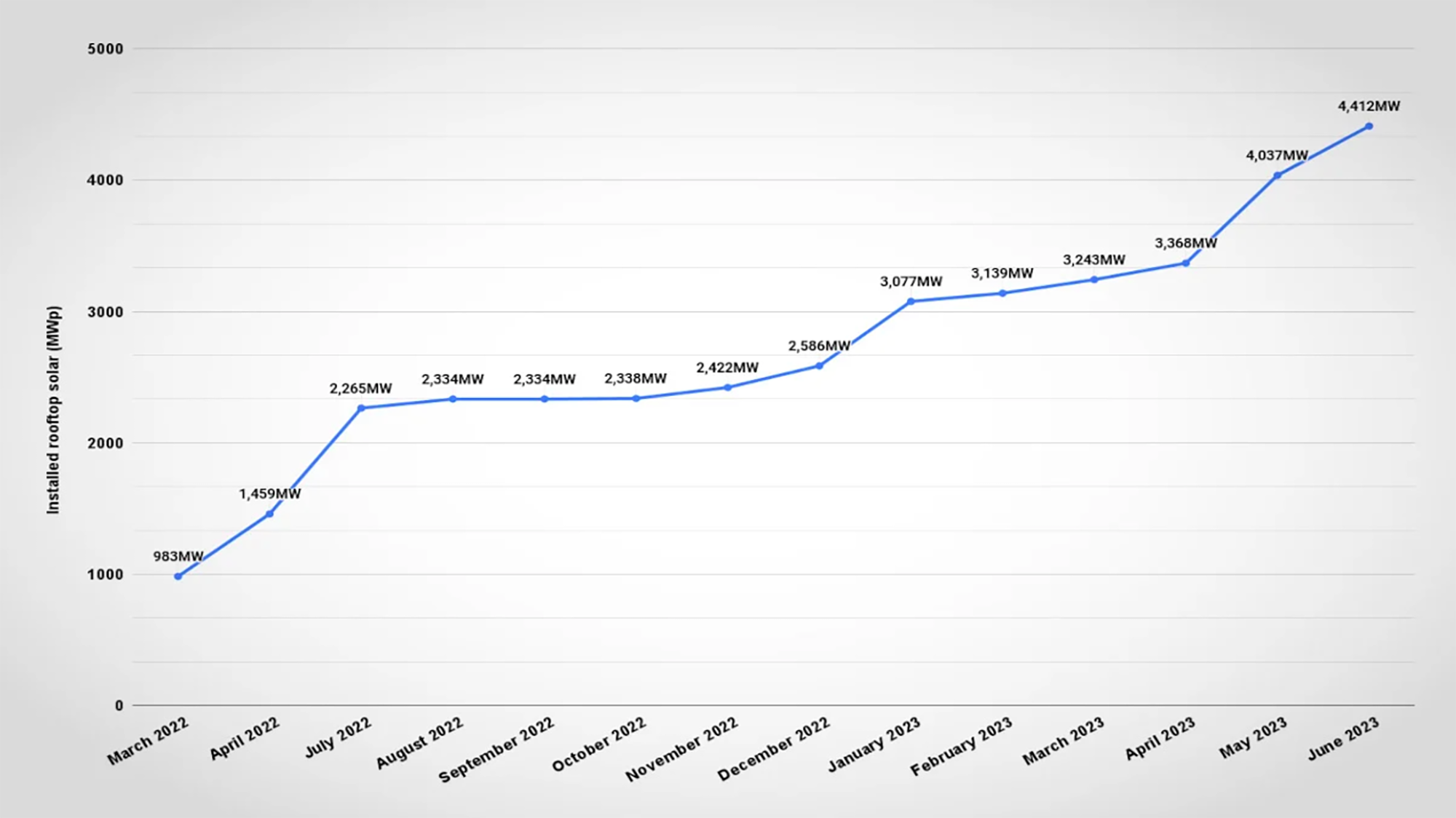

The exact scale of this bottom-up movement is now revealed in numbers recently released by Eskom reflecting the extent of rooftop solar installations across the country.

Solar panels on the roof of a house in Plattekloof, Cape Town, on 19 July 2022. (Photo: Gallo Images / Misha Jordaan)

Solar panels on the roof of a house in Plattekloof, Cape Town, on 19 July 2022. (Photo: Gallo Images / Misha Jordaan)

The Eskom data indicated that 4.4GW of rooftop solar had been installed by June 2023 – four times what it was in March 2022!

While utility-scale solar power costs about R12-billion per GW, rooftop solar is around 60% more expensive, at about R16-billion per GW.

If the entire 4.4GW is attributed to rooftop solar, this means we are looking at a total investment in rooftop solar by South Africa’s households and businesses of at least R65-billion – R54-billion since March 2022. (This excludes, of course, the sunk costs these installations depend on; ie the already existing electrical infrastructures in each household/business unit and its linkages to the distribution grids at street and neighbourhood levels.)

(Graph: Supplied)

(Graph: Supplied)

Installed rooftop solar

To put 4.4GW into perspective, compare this to the 6.2GW of installed renewable energy generation capacity built in terms of the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Procurement Programme (REI4P) since 2011 via the first four so-called bid windows; ie state-managed procurement of renewables via ministerial decrees and processes managed by the Independent Power Producers Office (IPP Office).

The 1.4GW of installed rooftop solar since January 2023 marks a key turning point: businesses and households are responding to the normalisation of Stage 6 load shedding by finding their own solutions.

By June 2023, the total number of load shedding hours for the first half of this year had exceeded that of the whole of 2022.

In February 2023, the minister of finance announced in his Budget speech a major tax incentive of 125% of the cost of a rooftop solar system for businesses and a small benefit for households.

Underlying the trendline from 983MW of rooftop solar in March 2022 to 4,412MW in June 2023 (and upwards since) are the risk calculations of literally thousands of businesses and households.

Whereas previously they took for granted that the state-run national electricity system would meet their energy needs, by 2023 a cultural shift was clearly under way. It reflected the fact that South Africans had given up on the possibility that this state-run energy system would ever get properly fixed.

It was time, they decided, to look after themselves.

For those who could afford it, the solution was obvious – a rooftop solar system comprising a 3kW system (including battery storage, inverter and even a solar hot water system) for the average middle-class household, and anything between 15kW and 10,000kW for small to medium-sized businesses (including farms).

The Jeffreys Bay Wind Farm in the Eastern Cape. (Photo: EPA / Nic Bothma)

The Jeffreys Bay Wind Farm in the Eastern Cape. (Photo: EPA / Nic Bothma)

Many large businesses like mines and even industries like Sasol have made similar big decisions to secure for themselves their own solutions by installing large – 100MW (ie 100,000kW) – systems in areas with reliable solar and wind resources.

Built by IPPs who get paid directly for what they generate by these corporates, these deals are enabled by so-called “wheeling agreements” with Eskom to secure access to the equivalent amount of power generated from the grid at the location where the energy is required.

Known as the “C&I” (commercial and industrial) space, there are upwards of 9GW (9,000MW) of these kinds of installations in the pipeline.

This estimate by the National Electricity Crisis Committee (set up after the breakthrough statement on energy solutions by the President in July 2022) is confirmed by the rising number of such installations that are registered with the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa).

By March 2023, 547 projects with a combined capacity of 2,839MW had registered with Nersa.

It’s all starting to add up

While there is obviously some overlap between the 4.4GW of rooftop solar and the 9GW of C&I projects, it is clear that this is all starting to add up.

Add in the 6.2GW of REI4P-procured capacity that already exists, plus the 2.5GW still to come from bid windows 5 and 6, plus the 10GW for REI4P bid windows 7 and 8 announced earlier this year by the minister of mineral resources and energy, and we are looking at around 30GW of installed renewable energy capacity. South Africa’s total energy system is only 48GW of installed generation capacity.

Although the efficiencies of renewables are only around 25% of the efficiencies of coal-fired power (unless you are comparing them to South Africa’s worst power station, Tutuka, with an EAF of 13%), it is now very clear that renewables are alleviating load shedding by at least two stages.

Add another 10GW of renewables to the grid over the next 18 to 24 months and that could bring rolling blackouts to an end (on condition, that is, that the performance of the coal fleet does not deteriorate).

The primary obstacle in the way of this solution is the limited capacity of the grid to connect more generators, no matter the technology. But that is another story.

Disorderly transition

What matters here is what some are referring to as the disorderly transition.

If Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy, Gwede Mantashe, had his way, renewables would play a small role. Instead, his dream would be another two or three giant coal-fired power stations and a fleet of nuclear plants (most likely Russian-built), all owned by a centralised SOE like Eskom (or the altogether new state-owned energy company he once touted).

But for this centralised dream to materialise, key decisions should have been made way back in the late 1990s/early 2000s, but they weren’t – and as he insists, he cannot be blamed for this.

Given the decade-long lead times for these kinds of mega-projects, coal-fired power and nuclear cannot resolve our immediate crisis. Hence the rise of renewables and the bottom-up societal response we are witnessing now.

Ironically, by resisting state leadership of the renewables solution that can potentially deliver cheap energy to all quicker than any other technology, the government has lost control of a market-driven solution enabled by sophisticated credit solutions created by the banks and turbo-charged by tax incentives.

While more electrons on the grid reduce load shedding, stimulate economic growth and prevent more job losses, it is equally true that the market-driven delivery of renewables will deepen rather than reduce our ever-worsening inequalities.

Mbeki’s apology

In 2008 President Mbeki apologised to the nation for ignoring Eskom’s insistent claims that new coal-fired power stations must be built. What followed was the rush to build two new coal-fired power stations (Medupi and Kusile) using Eskom’s internal capabilities (which were being hollowed out by State Capture) with disastrous consequences. The cost of Medupi and Kusile ballooned from a project cost of R163.2-billion in 2007 (for completion eight years later in 2015) to R450-billion by 2021 (without being fully completed by 2023).

But what are the implications of this bottom up response to worsening load shedding? Is this a disorderly transition? Does it help achieve a just transition? These are the questions we will address at our next public debate co-hosted by Daily Maverick and the Centre for Sustainability Transitions on 25 August.

It is now abundantly clear that the South African energy revolution is under way and unstoppable.

No matter how strongly the next Integrated Resource Plan insists on a so-called “technology mix” that includes coal and nuclear – even if there was someone who would fund coal and nuclear plants in South Africa (which there isn’t) – it would be at least a decade before they came online.

In short, coal and nuclear technologies cannot resolve the short-term energy crisis, nor can we assume that our fleet of power stations can be restored to their former glory (ie a 75% and above energy availability factor). The minister of finance has bluntly stated there is no finance available for this mammoth task.

Koeberg Power station. (Photo: Brenton Geach)

Koeberg Power station. (Photo: Brenton Geach)

Sure, we will most likely be burning coal to generate power for decades to come (which is why Mantashe is correct to insist the future is not entirely about renewables), and Koeberg’s life is being extended.

But new coal or nuclear seems unlikely. Even if the preference is for Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), these nuclear solutions will not be a commercially viable option before the mid-2030s.

In short, the indisputable fact is that renewables are the cheapest and quickest way to end load shedding. They will reinvigorate economic growth and get more electrons on to the grid for the benefit of everyone.

The problem for many in the ruling party is that the government has lost control of these bottom-up solutions. This may be one reason why the Cabinet-approved amendments to the Electricity Regulation Act have not yet appeared on Parliament’s agenda.

Without parliamentary approval, “wheeling” cannot be formalised, municipalities cannot play meaningful roles and the new Transmission System Operator cannot be fully operationalised.

However, numerous sub-national government responses are attempting to harness the developmental potential of renewables, reinforced by ambitious, locally funded corporate and community initiatives – 43 municipalities have promulgated feed-in tariffs. But without the formalisation of “wheeling” arrangements, this potential cannot be realised.

The cost of load shedding in the Western Cape in 2023 has been estimated to be around R12.8-billion by the Western Cape Energy Resilience Programme (WCERP).

Higher load shedding stages have left SMMEs vulnerable, but with even larger companies increasingly unable or unprepared to absorb those costs. According to the WCERP, the Western Cape faces the following challenges:

- Supply and reputational risk on exports and production;

- Negative effects on the tourism industry;

- Food insecurity due to decreasing production capacity leading to higher prices and social unrest;

- Worsening of the current economic recession, job losses, and loss of business and investor confidence;

- Electricity customers moving to own generation, which poses a risk to municipalities that rely on them for revenue; and

- High financial costs required to address immediate electricity constraints.

The Western Cape government has a critical role to play in this shifting and emerging energy landscape by providing enabling solutions.

The WCERP is the overarching plan that details the provincial government’s approach to ending load shedding and has two strategic objectives: 1) To reduce the impacts of load shedding on businesses and citizens in the Western Cape, and 2) To facilitate a lower level of reliance on Eskom in the Western Cape.

To reduce reliance on Eskom, the WCERP describes the reduction targets for the short, medium and long term:

- Short term (by 2025): Reduce off-take between 500MW-750MW;

- Medium term (by 2027): Reduce off-take between 750MW-1,800MW; and

- Long term (by 2035): Reduce off-take between 1,800MW-5.700MW.

Interventions to reduce the impacts of load shedding are as follows:

- Load shedding Relief Programme – such as emergency packs consisting of power packs being distributed to indigent households (and others);

- Provincial Integrated Resource Plan – including several options such as green and alternative energy sources;

- Demand Side Management Programme – the emphasis on the public’s role in reducing strain on the power grid wherever they can, aligned around incentivising and rewarding actions taken to reduce usage;

- New Emergency Generation Programme;

- Network Development Programme; and

- Increased investment in the energy sector – to attract financing for the implementation of the programme, to enable financing mechanisms to unlock implementation at scale and to attract local production.

George municipality’s electricity wheeling project attempts to understand and address the technical challenges that come with wheeling, as well as the policy, legal and regulatory reforms required to enable it.

Starting with one plant supplying four off-takers, this ongoing pilot project allows electricity supply from electricity generators in one area to be accessed by buyers in another, with George municipality charging a fee for the use of its municipal network to do so.

George municipality piloted wheeling services to steer alternative energy sources towards the municipal grid as a cheaper and more reliable alternative to electricity from Eskom.

The municipality approached wheeling as a metering exercise and became the first electricity provider in South Africa to pilot software that automates smart meter billing. The software, Access Energy, is freely licensed and hosted on municipal servers and allows the municipality to create and load its electricity tariffs and then apply them to a bill.

George municipality conducted a cost-of-supply study in 2019 to work out network infrastructure and operational costs. This has fed into how tariffs are constructed and compartmentalised, with energy reflected separately.

The wheeling model currently in use is that of surplus neutral, where Eskom’s charges are fixed, and therefore, where the electrons come from does not matter. This will change when various suppliers with various expenses are included, making smart metering and billing even more important.

Challenges noted from the pilot include the need for a standardised contracting process which would be the next step in taking wheeling forward for municipalities. It was noted in a presentation by the George municipality that wheeling only provides benefits to single customers.

Community-based projects

The Saltuba Community Primary Cooperative in Kwazakhele Township, Gqeberha, is one of several community-based projects spreading across the country.

Comprising 25 households, this cooperative pilot project is situated on municipal land which is zoned as public open space. The aim was to use existing land and infrastructure to generate income and sustainable livelihoods for residents.

Examples include rooftop rainwater harvesting, vegetable gardens on available land, and the sale of energy generated from PV solar panels back to the electricity grid.

Solar PV systems were installed in the form of a “carport” structure. Fifteen PV panels formed a roof specifically designed to show how the panels can be put on the roofs of houses, bigger buildings like schools, or on top of shipping containers. A primary cooperative is formed by residents of the houses around the solar array.

All residents are equal members within the cooperative and distribution of the income made from the sale of electricity is decided democratically. The cooperative provides temporary work in the construction and maintenance of the structures and makes employment decisions.

Major corporate initiatives are under way, with big names like Sibanye-Stillwater, Sasol, African Rainbow Minerals and Ekapa Mining in Kimberley leading the way.

Most of these initiatives will depend on “wheeling” to be fully operationalised.

Sasol and Air Liquide have decided to enter into a 20-year power purchase agreement with a consortium comprising Energy Green Power and Perpetua Holdings.

The consortium will build three 100MW wind farms in the Eastern Cape that will supply directly to the national grid. A wheeling agreement with Eskom will give the off-takers (Sasol/Air Liquide) access to equivalent power generated by the wind farms.

Sibanye-Stillwater has decided to procure 300MW of renewable energy from Red Rocket South Africa. The first phase will be a 100MW wind farm in Matjiesfontein, Western Cape. Energy generated by this project will be purchased by Sibanye-Stillwater, backed by a wheeling agreement with Eskom.

African Rainbow Minerals Platinum has entered into an agreement with Sola Assets to purchase energy from a 100MW solar PV plant that will be built near Lichtenburg, North West. The project will generate energy on to the national grid, coupled with a wheeling agreement with Eskom.

Ekapa Mining, a Kimberley-based diamond production company and the town’s largest employer, has decided to build a 22MW solar and wind plant on its land in the municipal area.

At a capital cost of nearly R500-million, this project will meet all the needs of the diamond production facility. However, during phases 2 and 3 of the project, Ekapa Mining would like to build an additional 100MW of solar and wind capacity to supply directly into the municipal distribution grid of the Sol Plaatje municipality.

This is a significant innovation that provides a model for other mid-sized towns where there is a dominant company that is prepared to provide land and risk capital to build a facility that does not impair the balance sheet of the municipality.

Instead of buying from Eskom, the municipality can buy energy directly into its own distribution grid. The off-taker agreement with the municipality provides the company with the security it needs to debt-finance the expansion of the plant beyond its own requirements.

A general pattern

All these examples of bottom-up action by municipalities, provinces, communities and corporates confirm the general pattern, namely that many different actors have decided to secure for themselves the energy they require.

They have given up on the most significant national infrastructure system that has materially unified all South Africans since 1994 – people who once depended entirely on this system to meet their energy needs.

As it breaks up, so too does the promise of affordable energy for all.

Like the rise of private security, private education and private healthcare in response to inadequate policing, public education and public healthcare, so too are we witnessing the rise of private energy for those who can afford to reduce their dependence on the national publicly owned grid.

This is not a recipe for a just transition. It is in reality a disorderly transition that has emerged in response to the failure of the government’s energy policies and strategies over at least two decades.

Can this bottom-up energy revolution be harnessed by the state in ways that reconcile the goals of a just transition with the widespread actions by households, communities, corporates, and local and provincial governments?

Contrary to those who praise the virtues of the market, it is not too late for the government to reclaim the ability to give direction to these bottom-up initiatives. A key step will be the establishment of the National Transmission Company of South Africa as the new owner and operator of the transmission grid.

Contrary to the social media campaign, this is not tantamount to privatisation. Once it is up and running, it can set the rules of the game, including procurement, pricing, trading and just distributional allocations. Of course, with a pro-market board and technocrat approach, it could make rules that counteract the just transition.

The second step is to create the conditions for mobilising large-scale private sector funding into the national energy system without compromising public value goals. This has started to happen, but blended finance solutions now need to go to scale. The Infrastructure Fund set up by the Development Bank of Southern Africa is a big leap in this direction.

Finally, we need to accept that the old way of doing things is rapidly dying.

The dream of a revived, centralised, state-owned energy generation, transmission and distribution system will never be realised.

The struggle for a just transition needs to take into account the new material realities and adjust accordingly.

This should include campaigns that are not just anti-privatisation, but also concrete proposals for more socially owned renewables and a much greater role for democratically governed, non-corrupt municipalities that – either on their own or in partnership with communities and/or corporates – emerge in future as key players in the new bottom-up energy revolution that is well under way. DM

Professor Mark Swilling is co-director of the Centre for Sustainability Transitions at Stellenbosch University.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=REeWvTRUpMk

Koeberg Power station. (Photo: Brenton Geach)

Koeberg Power station. (Photo: Brenton Geach)