Ferial Haffajee: I’ve spent Women’s Month delving into works by women—books, films, art—and the time I enjoyed most was attending your programme at the Oriental Plaza, which focused on the women of Fordsburg. How did you conceptualise this event?

Firdoze Bulbulia: My journey began with my political awakening in 1980 as a matric student, though it really started during the 1976 uprisings. That was when I began reading banned black resistance literature.

My time at Fuba (Federated Union of Black Arts), where I studied creative writing and dramatic arts, further cemented my interest in performance and storytelling. Influenced by the protest theatre of the eighties, I was fortunate to be part of the first audiences at the Market Theatre.

When conceptualising my PhD topic, I knew I had to weave in the activism of the eighties and the stories of my mother and grandmother, who were seamstresses in white, Jewish-owned factories by day, and clothing designers by night. They crafted glamorous wedding gowns adorned with diamanté, lace, and ribbons for their community.

The production included narratives from the Fordsburg Women’s Group. Fordsburg was a unique suburb — a lifeline and a battleground — that housed many anti-apartheid activists, the Defiance Campaign, and the Red Square. Capturing Fordsburg’s layered identity, with its rich Indian and Malay heritage and the activism of its youth, was central to my project.

I produced a full Fordsburg Women’s Group production, where my mother’s and sisters’ beautiful garments were displayed as a living exhibition alongside clothing from Mama Fatima Hajaig and my collection of protest T-shirts.

Tasleem Bulbulia’s clothes featured as an example of homegrown talent from Fordsburg. The designer has her studio in the industrial district. (Photo: Firdoze Bulbulia)

Tasleem Bulbulia’s clothes featured as an example of homegrown talent from Fordsburg. The designer has her studio in the industrial district. (Photo: Firdoze Bulbulia)

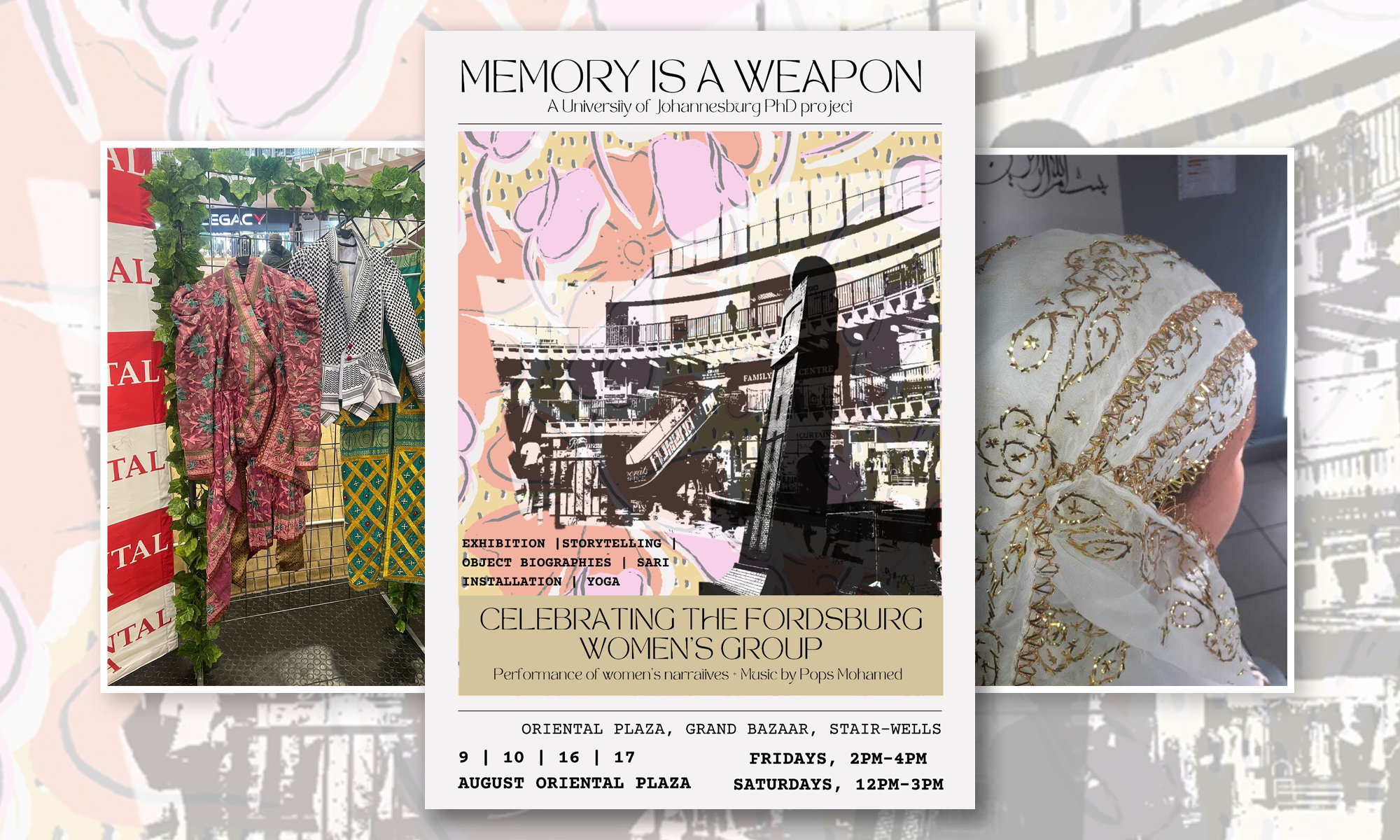

The flyer for the August programme for the women of Fordsburg. The title is taken from a poem by Don Mattera. (Image: Supplied)

The flyer for the August programme for the women of Fordsburg. The title is taken from a poem by Don Mattera. (Image: Supplied)

The performances were interspersed with Pops Mohamed playing the mbira and singing Mayibuye as we spoke about the women’s movement, particularly the Indian women of 1963 who marched to the Union Buildings in white saris against the Group Areas Act.

Incorporating academic literature on Indian indenture and post-memory, we aimed to theorise the intersection of memory and artivism. The result was #MemoryIsAWeapon — a reminder to honour comrades who were killed or went into exile and to keep their stories alive.

FH: As someone who grew up in the area, I remember the Fordsburg Women’s Group as a powerful force during a time of growing oppression. How did these women manage to forge solidarity and community?

FB: As young women, we found solidarity in each other and the Fordsburg Women’s Group. We were a close-knit group of activists who trusted one another.

The Group Areas Act had largely segregated us into Indian and coloured communities, making it easier to recognise each other and to be vigilant about potential spies. The Fordsburg Women’s Group organised community activities — from aerobics and keep-fit classes to extra Maths and English lessons, and health and wellness classes for new mothers and their babies. We also provided food parcels for the Vaal community. This shared purpose was our strength.

FH: Why is it important to preserve memory as a weapon, as poet and journalist Don Mattera so powerfully put it?

FB: It’s crucial that millennials and Gen Z understand our political history.

In the shifting political landscape, knowledge of our past is essential for making informed choices. Without this background, younger generations won’t have a solid foundation. We see figures like Helen Zille, with her iron fist approach, reminiscent of Margaret Thatcher. Without political training, today’s youth might not recognise the importance of memory in guiding their decisions.

In our youth, we believed that “memory is a weapon” because it reminded us of those who were killed or went into exile. We had a responsibility to keep their memories alive, and that responsibility continues today.

FH: The stories of the women from the Oriental Plaza, which you’ve been collecting as oral history, are largely unknown to me, despite having seen these women all my life. Can you share one of these stories?

FB: One story that stands out is that of Mrs Pharboo — Meenakshi and Dhiren’s mother.

She opened Cut-Rite, a men’s clothing store, while her husband ran a tailor shop in Newclare, making wedding suits for the coloured community.

Their home in Jeppe, across from the police station, was a safe house for activists during the worst periods of apartheid. The UDF (United Democratic Front) discussions often took place at her kitchen table, which she still has. Her husband is no longer with us, but they met when he came to work in her father’s clothing factory. The family is highly respected for their unwavering political support to many comrades.

FH: The sari was a prominent symbol throughout your programme. What significance does it hold for you?

FB: For many female Indian activists, the sari was everyday wear. However, it also became a symbol of protest, particularly the white saris worn by the women who marched to the Union Buildings.

The white sari symbolised mourning and resistance.

Activists like Fatima Hajaig, Amina Cachalia, Kamla Naran, and Priscilla Jana wore them as they fought against apartheid. I’m proposing a sari installation at the Oriental Plaza as a lasting tribute to the activism of Indian women. The sari also symbolises “indenture”, connecting us to our heritage and the struggles that came with it.

A wedding headdress intricately embroidered and pinned to brides in the Malay community. A tradition handed down by immigrants from Indonesia and Malaysia. (Photo: Supplied)

A wedding headdress intricately embroidered and pinned to brides in the Malay community. A tradition handed down by immigrants from Indonesia and Malaysia. (Photo: Supplied)

FH: You featured an exposition of wedding dresses and the Medora, which are often overlooked as art forms. Why did you choose to highlight these?

FB: The overarching theme of my work is “we are not invisible”. My wedding gown showcases the beauty and craftsmanship of my mother, grandmother, and sisters—all of whom are clothing designers. I wanted to emphasise their artistry and the sheer magnitude of their creations.

When the Malay banjo player and singers performed Rosa, I brought out my wedding gown because the song is traditionally sung at weddings.

The theatre aspect of my work draws from Bertolt Brecht’s “epic theatre”, a style that aims to provoke rational thought and social change rather than emotional engagement.

I wanted to present reality and beauty in both an epic and glamorous way while also confronting the painful reality of “invisibility” if our narratives are not included in the academic canon.

FH: How did the contemporary Fordsburg community respond to your programme?

FB: The response varied depending on who you consider a contemporary Fordsburger — local or foreign. The Pakistani and Bangladeshi passersby were intrigued, asking questions, while locals stopped, enjoyed the show, and moved on.

The renowned South African musician Pops Mohamed performing at the Oriental Plaza. (Photo: Firdoz Bulbulia)

The renowned South African musician Pops Mohamed performing at the Oriental Plaza. (Photo: Firdoz Bulbulia)

Mrs Pharboo and her daughter Meenakshi Pharboo. The family’s homes were refuge to activists who had to go underground. Their store, which they still own, supported the anti-apartheid cause. (Photo: Supplied)

Mrs Pharboo and her daughter Meenakshi Pharboo. The family’s homes were refuge to activists who had to go underground. Their store, which they still own, supported the anti-apartheid cause. (Photo: Supplied)

The artivist and film-maker Firdoze Bulbulia at the Oriental Plaza (Photo: Supplied)

The artivist and film-maker Firdoze Bulbulia at the Oriental Plaza (Photo: Supplied)

The older locals, however, came back for more and were very supportive. Many thanked me for bringing back the stories, especially the Ratiep show and Indian dance, which resonated deeply.

Female shop owners expressed their gratitude for including their stories — they felt seen and empowered.

Raeesah Jassat, a young woman from Style Fabrics, was humbled and delighted; it gave her the courage to learn more about her family’s history and the ownership of their store. Aneesah from Fashion Centre, who owns an all-female clothing store, was overjoyed that her children would now better understand her worth and accomplishments.

The Mohamed sisters, who shared their concerns about the lack of foot traffic, were pleased that on the days we exhibited, they actually had customers.

The Medora, part of my Malay heritage, is something we often wore as bridesmaids, though we thought it was “old-fashioned” at the time. I wanted to share this art form as part of epic theatre, showing the magnificence of our cultural heritage, especially in a university setting where diversity and inclusion are paramount. DM

Photo: Supplied

Photo: Supplied