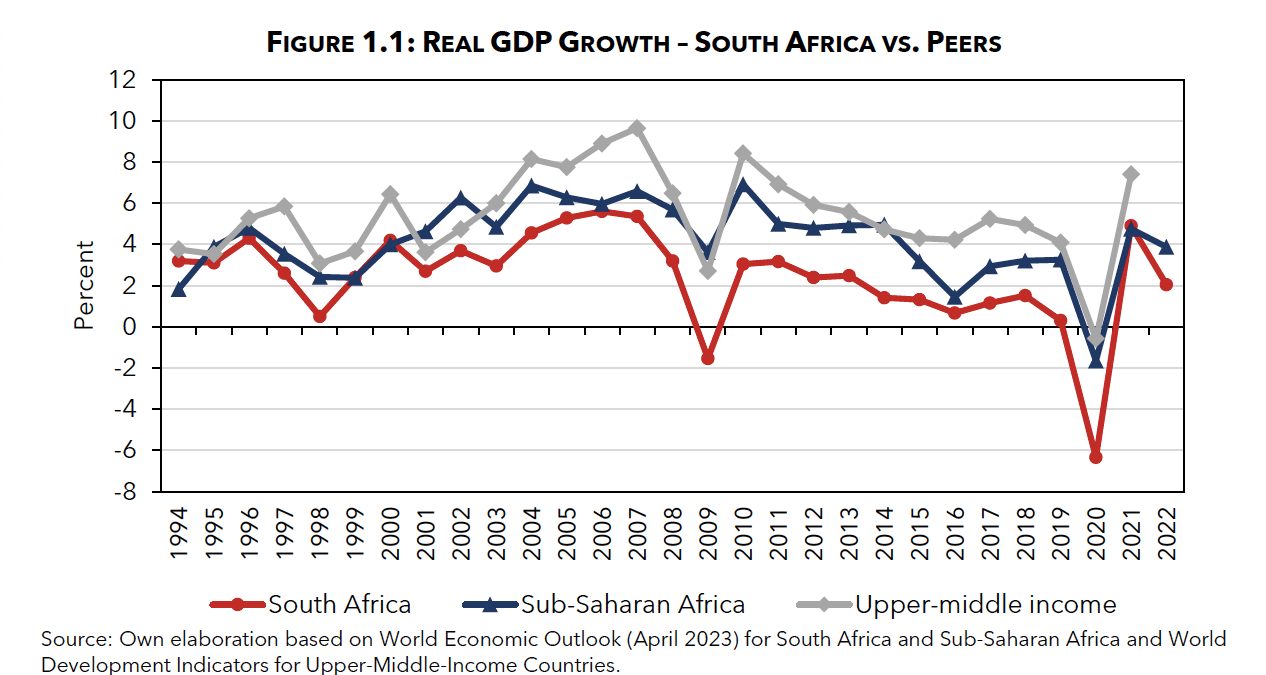

The report, Growth Through Inclusion in South Africa, lead-authored by development economist Ricardo Hausmann, seeks to explain why South Africa’s economy has consistently failed to grow at the same pace as its peers, with horrendous social consequences. (See graph below).

A product of the Growth Lab, an internationally recognised arm of Harvard University, its findings will be high on the radar screen of rating agencies and foreign investors. “... [T]wo issues — collapsing state capability and spatial exclusion — together leave South Africa’s enormous potential in its people, land, assets and capabilities underutilised. Achieving a better economic future will require addressing both constraints,” the report says.

“Unlike a natural disaster, which is followed by a recovery when the disaster recedes, South Africa’s collapse in state capability will continue to erode if systemic causes are left unaddressed.”

State collapse is, of course, not news to a South African audience. But the report takes a deep dive into the issue and its findings, based on two years of intensive applied research, confirm what many South Africans have long surmised.

Bitter pill for ANC

This will make it a bitter pill for many in the governing ANC to swallow. Keeping to that analogy, it is like a top team of doctors offering a similar opinion about the ailments of the body politic that is based on detailed and in some cases original diagnoses.

“The deeper causes of collapse stem in part from ideological gridlock within government, which has prevented critical decisions from being made in time, as has happened repeatedly in both electricity and rail.

“It also stems from a particular ideology that prevents society from contributing to supply societal needs; for example, by limiting private, provincial and municipal power generation,” the report observes.

“It also stems from the mistaken belief that preferential procurement rules could be imposed on complex organisations... at little cost. These rules have instead — in many cases — overburdened critical public organisations.

“South Africa also has a peculiar form of fiscal decentralisation that has overburdened many municipalities that do not have the local capabilities to match the responsibilities.”

The report also takes aim at patronage and cadre deployment, adding its analytical weight to a scourge highlighted by the Zondo Commission and the government’s many critics.

“South Africa has seen a rise in political patronage, which has interacted with the other causes of state collapse. Together, these interacting causes of state collapse have created a vicious cycle where talent becomes harder to attract and retain in government, yet talented public servants are needed to restore and rebuild state capacity.”

This has removed many of the competitive advantages that made South Africa the continent’s most industrialised economy.

“The collapse in state capacity to deliver key inputs has, in effect, squandered the country’s comparative advantage in cheap, coal-fired electricity... but it has great potential to develop new green growth drivers that will help to supply global decarbonisation,” the report notes.

Spatial exclusion

“Spatial exclusion”, rooted in rigid apartheid zoning but exacerbated by subsequent policies, is seen as another major constraint on economic growth.

“Despite three decades of explicit efforts to reverse this spatial exclusion, post-apartheid policies have done little to address spatial inequality of job opportunities.

“Whereas regional divides are not uncommon along the path of economic development, the extent to which South Africa is unequal in space is unique,” the report says.

On this front, the report compares South Africa to Mexico, which has a similar-sized GDP, and asks why both countries have similar formal employment rates but huge differences in informal rates of employment.

What it finds, drawing on a Harvard research paper from 2022, is that relatively, transport costs are the gaping pothole in this road to development.

“... high transport costs (direct costs and time costs) create a wedge in the South African labour market that reduces employment,” the study says. This brings us back to state failure and the collapse of Prasa – another example of a vicious cycle that mostly impacts black South Africans.

“We... find strong evidence that formal jobs are limited because long commutes from low-density areas in and around cities make transportation costs and reservation wages high, while low residential densities prevent the development of a thriving informal economy. Meanwhile, rural former homelands continue to be economies separate and distinct from the rest of the country.”

The report does have some sensible recommendations to address these challenges, including eliminating cadre deployment.

“An example would be broader civil service reform that changes the appointment of civil servants especially for more technical positions into a more merit-based system rather than one that is overly influenced by politics,” the report says, adding that “civil service rotation” across the country should also be explored.

“By recruiting talent nationally and deploying individuals in multi-year appointments across geographies, South Africa may be able to better bridge gaps in capabilities across municipal governments over time. For example, the experience of India in developing a prestigious civil service system — e.g., its Central and State Engineering Service — is illustrative of what such a system can look like.”

Allowing more private sector investment into the energy space – which is being done anyway as businesses and households scramble to mitigate the impact of power outages – is also on its list.

Embracing the potential of the green energy transition is another.

On the spatial divide, the report recommends “a relaxation of overly restrictive building and zoning regulations that greatly limit the development of denser housing.

“Zoning and building regulations are locally determined, but South Africa’s national and provincial policies can incentivise a revolution in urban regulations that would allow city centres to ‘build up’ and become centres of safe, accessible housing.”

For many South Africans, these suggestions are no-brainers.

The importance of this report is that it reaffirms the domestic diagnosis of many of the government’s critics with a trenchant analysis of the situation by one of the world’s leading centres of development and economic thought.

This may be seen as a case of singing to the choir, but, hopefully, some policymakers with political heft will also pay heed to the lyrics. DM