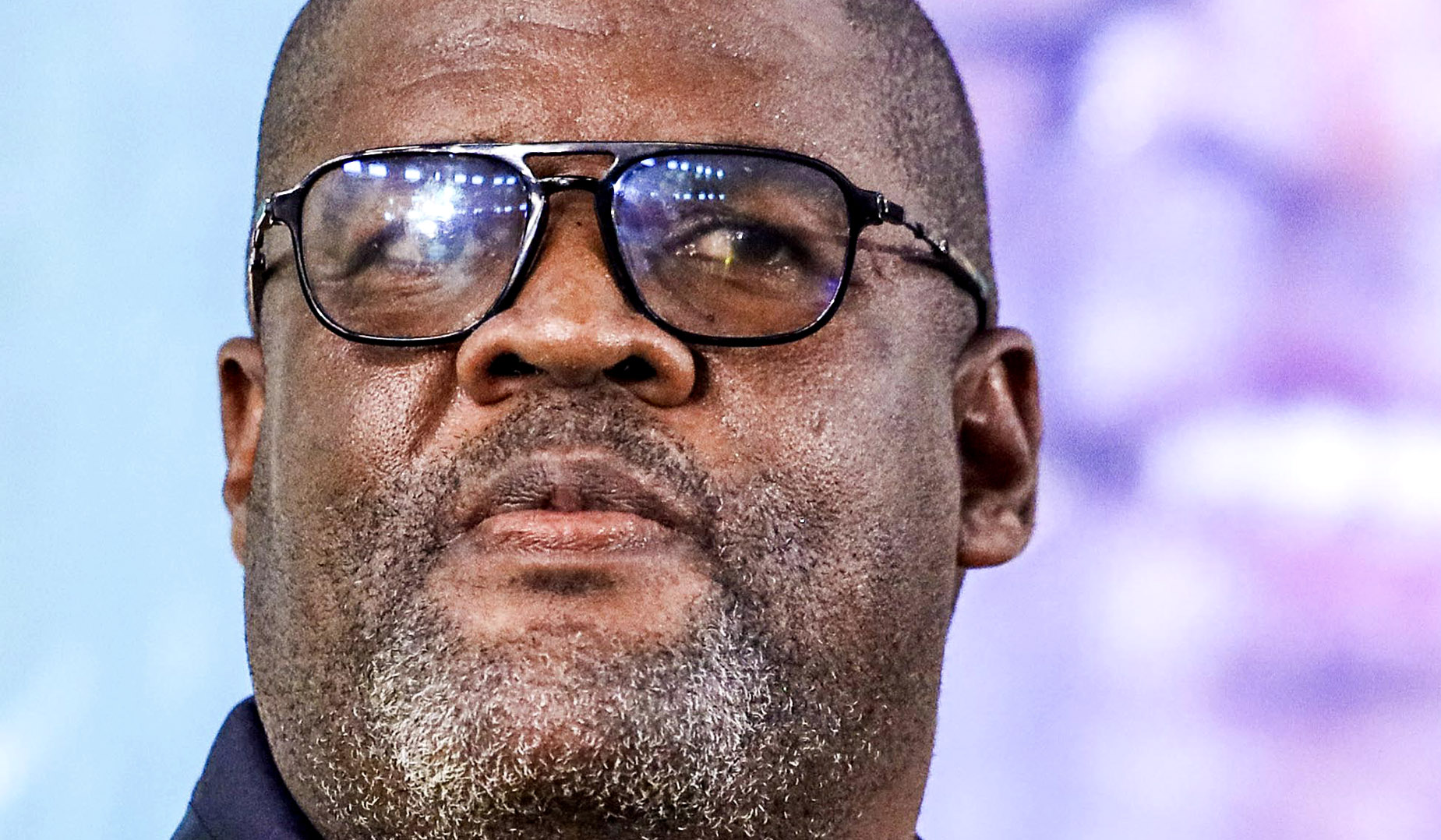

The leader of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) and newly appointed Minister of Land Reform and Rural Development, Mzwanele Nyhontso, has promised to hit the ground running and tackle land dispossession in South Africa, which he has termed the ‘original sin’.

Every stakeholder in the sector will be closely watching his moves and listening to his words, particularly since he comes from the PAC, a party that has defined its historic task as returning the land to the people. This encompasses a hardcore stance of land repossession that goes beyond expropriation without compensation.

Since its formation in 1959, the PAC has viewed the ANC’s stance on land – based on the Freedom Charter – as a compromise.

The Freedom Charter states: “The Land Shall be Shared Among Those Who Work It! Restrictions of land ownership on a racial basis shall be ended, and all the land re-divided amongst those who work it to banish famine and land hunger.”

It came as no surprise when the PAC continued being critical of the “willing buyer, willing seller” principle adopted by the ANC in dealing with land restitution in South Africa post-1994.

The involvement of the PAC in the government of national unity signals a shift in approach towards the land issue.

The minister has already said he will be dealing (hastily?) with the backlog of unresolved restitution issues. He has also promised to focus on rural development as a way to discourage people from migrating from rural areas to cities in search of employment.

Nyhontso wants development and economic rural citizenship to be a key focus of his work. To do this, he will need a lot of players to be involved, the most significant among them being rural residents themselves.

He will need civil society, traditional authorities, developers and his department to work together to craft a new path.

Many challenges lie ahead of him, especially from a policy perspective. For instance, rural development is held back by policy uncertainty as no law deals with land tenure security in rural settings on customary land.

His predecessors have failed to enact permanent legislation. As a result the Interim Protection of Informal Land Rights Act 31 of 1996 (Ipilra), which is a stand-in law, has been renewed every year since 1997.

This law is important as it protects vulnerable community members from ill-intentioned developers. It is inevitable that when developments such as mining ventures and the building of roads and dams happen, the question of decision-making on the land will create conflict between developers and rural citizens.

To avoid these conflicts, which often lead to projects either being cancelled or delayed, leaving rural citizens disillusioned, we need a permanent law that takes over from Ipilra. Such a law needs to keep the key protections in Ipilra, such as the consent requirement, whilst improving certain aspects of the law.

This should be done by understanding citizens’ customary practices to give effect to flexible and current methods of land ownership and land rights security based on the world-view of rural citizens. This may go a long way in creating policy certainty, which is often said to be the deal-breaker in an investment.

It is the state’s responsibility to protect the most vulnerable. And it is in the interests of developers to work around given policies to create wealth. It is as simple as that.

Land redistribution is a mess. The land claims backlog is just the tip of the iceberg.

There is land that has already been claimed and is currently under the authority of legal entities called Communal Property Associations (CPA). Many are dysfunctional because the state has not played its regulatory role. As a result, there is a lack of accountability; no one ensures that elections occur as required, and those elected to leadership positions within the CPA do not leave office after their term ends.

The challenges here seem to point to the government’s failure to consult affected communities when designing instruments that ought to be used by rural citizens.

There are also community trusts which are paraded by the state and developers as shareholding instruments, especially in rural mining communities.

There are just too many problems, as our current research on community trusts on the platinum belt has found, but at the centre of these challenges is that there is no law guiding these trusts.

In fact, the only trust laws that exist were never even designed for communities – there is no reference to community trusts in our laws. This indicates there is still a huge gap in legislation that could help rural citizens manage and govern their properties for their own benefit. This puts rural communities in a precarious position as most end up losing their land rights without getting adequate compensation.

Instead of the state creating land rights protections and policy certainties, it has been usurping the rights of rural citizens to make decisions about their land.

The creation of laws that allow traditional leaders to enter into third-party agreements without the consent of the affected landowners is an example of this.

Instead of activists working towards the return of the land that has been lost, they spend time and resources trying to safeguard the little land that remains in the hands of the victims of colonialism and apartheid.

Minister Nyhontso must ensure that his department is aware of all policies that affect rural land issues if he hopes to move rural citizens’ land struggles forward, develop the rural economy, and put his PAC back on the path of defending the land that is in black hands – while carving a clear plan to deal effectively with the original sin. DM

Ncedo Mngqibisa is a researcher and land activist academic at the Land and Accountability Research Centre, UCT. His research focuses on the security of tenure, land resource management, and the agreements struck between mines and land owners, the forms of consultation claimed and conducted and, the benefit, if any, to ordinary members of these communities. Mngqibisa has substantial ethnographic research experience, and is an experienced development facilitator in land and governance.

This article is more than a year old

South Africa

New Minister of Land Reform Mzwanele Nyhontso has a mammoth policy task ahead

It is the state’s responsibility to protect the most vulnerable. And it is in the interests of developers to work around given policies to create wealth. It is as simple as that.