The catalogue of memories in my mind has been playing on repeat since I first heard the news that Jackie Selebi had died on Friday morning. I’ve vacillated from sadness to relief to annoyance to regret and even vindication as I’ve struggled to find an appropriate response to his death. Judging by the vociferous debates on social media, I suspect that I am not alone in this dilemma and that my reaction mirrors that of the rest of the country.

How do we remember this man who left such a complex legacy – do we demonise and vilify or do we refuse to speak ill of the dead as some cultures dictate, choosing instead to idolise and applaud?

My experiences of Jackie Selebi covered the full spectrum. I witnessed his spectacular fall from grace first hand, from his powerful position on the seventh floor of the Wachthuis building in Pretoria’s CBD to the dock on the fourth floor of the High Court in Johannesburg. A large portion of my career as a journalist has been dedicated to following his actions and over a decade I grew familiar with him.

One of my earliest memories of Selebi as a young reporter is from 2002, when the police foiled a massive drug deal in Kya Sands, seizing 1.2 million mandrax tablets. The Nascom, dressed in his uniform, his epaulets gleaming and his cap on his head, smiled like a Cheshire cat for the news cameras, holding up a clear plastic packet stuffed with pills. He looked every bit the image of the crime fighter. What we didn’t know at the time was that his personal shadowy police unit Palto had been involved in the deal and his friend Glenn Agliotti had played a pivotal role, but Selebi had chosen to ignore that, seizing the opportunity for media acclaim instead.

As National Commissioner, Selebi surrounded himself with fiercely loyal lieutenants who would defend him at all costs. He portrayed an image of unshakeable power and as the first rumblings began to emerge that he may be in the pocket of criminals, those closest to him closed ranks and flat out denied it. They issued statements insisting the allegations that their boss had been caught up in a massive international network of drugs and crime was merely a product of the ongoing battle between the Scorpions and the police. A vendetta, a conspiracy, an agenda, they insisted.

I remember those long months in 2006 and 2007 when the cloud of doubt sat firmly above Selebi’s head. The entire country knew about his friendship with Glenn Agliotti, ‘finish and klaar’, but President Thabo Mbeki refused to act against his friend, saying he had no evidence to substantiate the claims. I remember September 2007, when National Director of Public Prosecutions Vusi Pikoli was suspended from his position by Mbeki; to this day Pikoli maintains it was for his relentless pursuit of Selebi. Warrants of arrest for the police chief had been secured and then suspiciously scrapped. The country knew that Selebi had a case to answer to, but he remained defiant. I remember watching in December of that year, in the mud of Polokwane, when Selebi strolled around the ANC conference looking relaxed in a pair of shorts and his SAPS cap, indifferent to the imminent charges coming his way.

Selebi was proud and in power. He had a laissez faire attitude. ‘Let them come’, he challenged. ‘These hands are clean’, he assured.

And come the Scorpions did, charging the country’s most senior cop and the head of Interpol with corruption. In February 2008, I watched as a bevy of intimidating officers in black leather jackets crowded around the steps of the Randburg Magistrate’s court, manhandling journalists and strong arming their authority. They hid Selebi from view during his first court appearance, but the commissioner popped his head out from behind their bulking frames, to grin at the cameras and give a little wave.

I’ll never forget how Selebi stood in the dock for the first time, and snorted in disgust at the magistrate.

Selebi would go on to spend more than fifty days there, as evidence was led against him. The country heard astonishing testimony of envelopes stuffed with cash being slid across boardroom tables, of shopping sprees to Sandton City and gifts of luxury handbags and of cheque stubs reading ‘Cash Cop’, ‘JS’ and ‘Chief’. Glenn Agliotti, the self styled Mafioso, the ‘Don’, revealed how he had sold access to Selebi for millions, in exchange for protection from the police. But beyond that, we heard alarming evidence of how Selebi’s loyal lieutenants at the SAPS had resorted to dirty tricks to protect him. It was the stuff of shady deals in smoke-filled rooms.

Each morning Selebi would arrive at court with his largely Afrikaans legal team, clutching a square foam pillow, reading ‘Pavarotti in Africa’. The incongruity was obvious to all of us in the public gallery.

During the lunch breaks, he would slowly climb the stairs to the back of the room and make his way down the passage to a hard wooden bench next to a window. Occasionally he would jerk his head in my direction, beckoning me to come and sit with him. He was spitting mad and deeply bitter about the fact that he was being subjected to such a demeaning display, having to stand trial like a criminal. He would click his tongue and his nose would crinkle as he ranted about forensic consultant Paul O’Sullivan’s involvement in the case and how he had been the target of a political conspiracy orchestrated by Pikoli and Bulelani Ngcuka to ensure the survival of the Scorpions. He was adamant that the entire trial was a farce, a plot set against the backdrop of the ugly police vs Scorpions battle. He even suggested that judges and senior politicians had been complicit.

Often he would shape his forefinger and his thumb into a gun and ask ‘Where is the smoking gun?’. He didn’t believe Gerrie Nel and his team had anything that would stick. Selebi promised that he would prove his case, divulging that he had video tapes and audio recordings that would blow the state away. He also promised that the TVs would be rolled in and I would see this for myself. The TV screens were rolled in, converting courtroom 4B into a surreal move theatre, but the evidence wasn’t nearly as explosive as he had promised. He never produced the so-called ‘Spy Tapes’ that he had played a central role in securing – the same spy tapes that had saved Jacob Zuma from a corruption conviction, ensuring his Presidency.

During these lunch breaks he would stroke his mustache and munch on his apple, never eating anything more, saying he did not have an appetite. Before long, his suits became baggier and his frame slighter. His brow increasingly creased and the pall of his skin grayer. The trial was taking its toll and it became obvious that Selebi was not well. Would he be able to take the stand, I wondered?

His legal team was desperate to keep him away from the witness box. So too was his wife Anne. He was too bitter, too angry, too resentful. It was all too personal and he would not be able to keep his composure. They knew he would implode.

But above all, Selebi was stubborn. And arrogant. He insisted on testifying in his own defence and this would prove to be the most fatal flaw in his strategy. The death blow to his case. We watched as the man, once deeply respected and highly regarded, self-destructed before us. He lied over and over again. He presented forged documents to the court. He claimed his wife had shredded receipts. He looked as though he had lost his mind. It was a devastating spectacle to witness.

His lawyers tried to explain it away by saying that he was ill. That he may have early onset Alzheimers but he refused to see a doctor. I had little doubt that he was already sick – this was obvious from his physical appearance. But I didn’t believe that it was illness that caused him to implode on the stand – it was his own hubris that tore him apart.

That will be my most indelible memory of Jackie Selebi - running from the shame of his lies on the witness stand, the uncomfortable awkwardness and embarrassment of it all. Mostly, I will remember the terrible sadness of watching him descend from what he once was to what he had ultimately become.

This is the dilemma that I have faced over the past few days, as I wondered about how should I remember Jackie Selebi. Competing with this image of him in the witness box, is another indelible memory of him sitting at home in Waterkloof on his couch, surrounded by animal print scatter cushions, watching ‘Yanni Live from the Acropolis’ and discussing the merits of 'John Perkins’ Confessions of an Economic Hit Man'. He had agreed to allow me to come and interview him at his house and he had spent an hour expounding on how much he valued the work that he had done at the SAPS and the team that he had worked alongside. He sounded like a leader and a committed cadre. Sure he spent a big chunk of the time raging about the case against him, but primarily he was concerned with getting back to his office to lead the police. This was the Selebi that was once the President of the ANC Youth League, who had been a highly acclaimed diplomat, South Africa’s ambassador to the UN in Geneva, a freedom fighter and a member of the ANC’s NEC. This was the Selebi that had earned the respect and loyalty of his fellow politicians and police officers.

I remember asking him if he would ever bounce back, if there was still more to come from him once the criminal trial had run its course.

‘Eh, it sounds like an obituary,’ he chuckled before adding, ‘That you will see. Lots more’. He insisted that he had ‘no regrets, maybe some mistakes, but no regrets’.

In writing Selebi’s obituary that he had prematurely laughed off, I came across an old column by a fellow former diplomat Isaac Mogotsi, who worked with Selebi when he was the Director General of Foreign Affairs. Mogotsi described his old colleague as ‘a former Soweto teacher, obese, with a penchant for self-deprecating jokes, fierce temper of a provoked African mamba, deep and hearty laughter, intemperate and coarse language of an Odessa sailor, hangman’s decisiveness and determination, a great heart, and a very forgiving disposition, but also too trusting of human beings, whatever their background’.

While Magotsi believed that Selebi was arguably post-apartheid South Africa’s most successful multilateral diplomat, he had some doubts:

‘But even in his exile and diplomatic halcyon days, there was something about Selebi that made him seem like a bad accident waiting to happen, something that made him forever appear like one of those deeply flawed but transformational heroes from Thomas Carlyle’s “On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History”. As Thomas Carlyle would say about his Heroes, “their heroism lay in their creative energy in the face of difficulties, not in their moral perfection”. So it was with Selebi – impetuous, explosive temper, intimidating, his ability to bear long grudges, his propensity to think and make decisions on his feet, his tendency to cultivate a close-knit but exclusionary circle of absolutely trusted confidants, and his flashes of typical school ground bully tactics – all these weaknesses on Selebi’s part were often on display, and were part of his legend since I got to know him in Maputo exile in 1980.’

I realize now why I have had such vacillating emotions in response to Selebi’s death. He was such a complex character and was such different things to so many people. It’s far too simplistic to pigeonhole him into the category of corrupt dirty cop or flawed freedom fighter or heroic patriot.

To his attorney Wynanda Coetzee, he was ‘a very proud and caring person with an extraordinary insight in and understanding of political and social issues, often recounting interesting stories regarding experiences whilst in exile without any bitterness towards apartheid’.

To a member of the Scorpions team that pursued him he was a ‘criminal who sadly allowed criminals to influence him’.

I’m sad that he has died, but even more so about the legacy that he leaves behind. His fall is undoubtedly one of the greatest tragedies of our post-democratic South Africa.

So as the catalogue of memories plays on repeat in my mind, I will remember Selebi with all the complex nuances – the portly waddle, the shame, the disgrace, the hubris, the disgust, the lies, the family loyalty, the passion, the self deprecating humour, the patriotism, the indefatigable insistence of his innocence and the overwhelming evidence of his guilt. DM

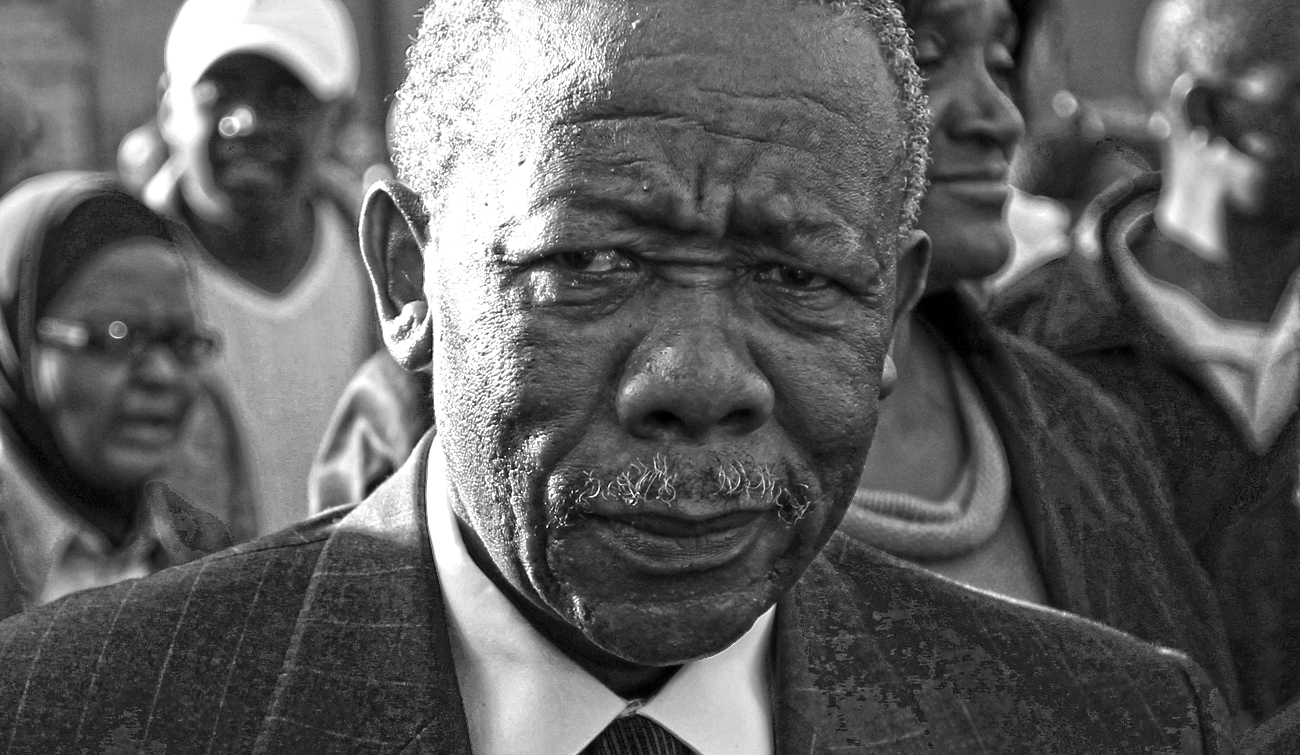

Photo: Jackie Selebi, the former head of South Africa's police force, leaves after his appearance at Johannesburg High Court August 2, 2010. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko.