Over three days in May and June this year, I gave detailed evidence to the Zondo Commission about the hard evidence of State Capture – when, where and how the money flowed to what I call the Gupta enterprise, and how much that has cost the people of South Africa.

That evidence formed part of a report running to just under 500 pages (excluding a 77-page Executive Summary). In total, my report and evidence bundle runs to 7,023 pages, including extensive banking documentation.

I am very aware that this is a lot of complicated-sounding material. But I’m also equally convinced that this material is too important to ignore.

So, over five short instalments, I will be publishing an explainer of the evidence, working through my report from beginning to end, and pointing out some of the more incredible and outrageous stories along the way.

Today, I will set out how much money the state paid in contracts tainted by State Capture involving the Gupta enterprise, and discuss a hitherto unknown R7.8-billion State Capture contract involving T-Systems.

In my second instalment, I’ll explain and enumerate how much the Guptas earned from State Capture, how I calculated this, and discuss those cases that might have slipped under the radar.

In my third instalment, I’ll talk about how the Gupta enterprise laundered their money in South Africa, and how they moved that money abroad.

The fourth instalment will look at how the Gupta enterprise’s money laundering network was used and piggybacked on existing organised criminal networks both locally and abroad.

Finally, the fifth instalment will look at how the Gupta enterprise used the criminal money they earned through State Capture to buy more assets in South Africa – assets that they then used to further loot the state. To explain this, I’ll use the example of how the Guptas purchased Optimum Coal with R1.8-billion worth of criminal money.

Before I do so, however, I want to make something clear: this research was only made possible by a team of dedicated legal and forensic researchers, advocates and deep diggers at the Zondo Commission who have been diligently collecting millions of pages of crucial banking information, following leads and money trails as far as is humanly possible.

For all the concerns about the length of time the Zondo Commission sits, it must be remembered that this process is truly, globally, unique. Nowhere else in the world right now, and possibly ever, can point to anything near the depth of investigations into grand corruption as is being pursued in South Africa.

Paul Edward Holden testifies at the State Capture Inquiry. (Photo: Gallo Images / Papi Morake)

Paul Edward Holden testifies at the State Capture Inquiry. (Photo: Gallo Images / Papi Morake)

The total cost of State Capture involving the Gupta enterprise

R57,064,461,144.82.

That is the total amount of money that the South African government spent on contracts tainted by State Capture involving the Gupta enterprise.

You may have read a different figure a month ago of over R49-billion. That figure, which formed part of my original evidence, excluded a new mega-contract that was tainted by State Capture involving Eskom and the IT supplier T-Systems. I’ll talk about that contract more below.

I calculated this figure simply: I worked with the commission to identify the contracts awarded by the South African government where they were tainted by State Capture and how much was paid against them.

This was quite a wide definition, but the essence is that the contracts involved and benefited the Gupta enterprise in some way, most notably where the Gupta enterprise eventually took a cut. In some cases – in fact, the vast majority of cases – the involvement of the Gupta enterprise was an obvious and clear predictor of some sort of irregularity in the awarding of contracts by the state.

In a small number of cases, however, the involvement of the Gupta enterprise didn’t necessarily mean that the original contract was corrupt or irregular. Instead, in the fulfilment of that contract, money flowing from State Capture was used. One example of this is the R250-million loan given by the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) to enable the Guptas and their partners to buy Shiva Uranium. There is no evidence that the IDC made the loan irregularly. However, in paying back a portion of the loan to the IDC, the Guptas made use of money sourced from other State Capture money flows.

Two further things should be emphasised before I move on.

First, these are State Capture contracts linked to the Gupta enterprise only. They do not include, for example, the horrific looting of the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa and many other cases of grand corruption.

Second, when I say the cost of Gupta-linked State Capture, I mean only the amount of money paid by the state in contracts. I do not calculate the opportunity cost, or the real, long-term and profound social cost of State Capture, that has included denuding the state of its abilities to realise its citizens socioeconomic rights.

But I am very confident that this amount would be orders of magnitude more than the R57-billion figure I quote above.

The five biggest earners

State Capture earned a number of companies, both multinational conglomerates and South African entities, serious money.

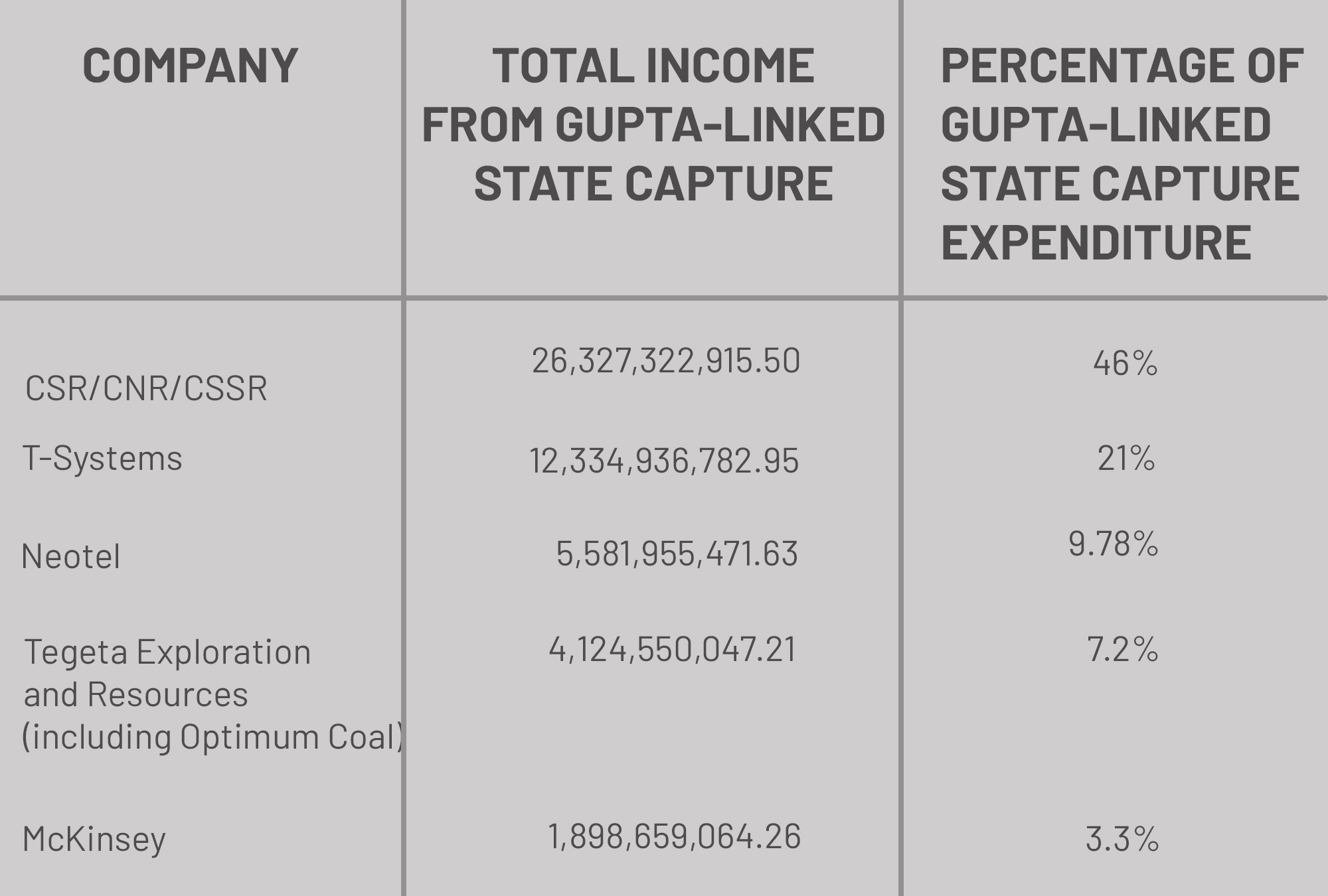

The contractors that received the most amount of money in State Capture related to the Guptas were China South Rail, China North Rail and the company they formed when they merged, China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation (CRRC).

These three companies were awarded contracts to deliver locomotives (and associated services) by Transnet: 95 “20E” electric locomotives, 232 “45D” diesel locomotives, 100 “21E” electric locomotives and 359 “22E” locomotives. In total, these companies were paid R26.32-billion by Transnet – 46% of the total value of all the contracts I identified that were tainted by Gupta State Capture.

In my next piece, I’ll talk about the kickbacks earned by the Guptas from these contracts – over R7-billion.

The second-biggest recipient of Gupta-related State Capture contracts was T-Systems. T-Systems is an enormous multinational conglomerate with headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany. It is a subsidiary of German giant Deutsche Telekom, which is part-owned by the German government. Deutsche Telekom reported total revenue of €101-billion in 2020.

T-Systems was awarded two huge contracts (referred to as Master Services Agreements or MSAs) to supply IT services and equipment rental to Transnet and Eskom; their connections to the Guptas is discussed below. In total, T-Systems was paid R12.3-billion. That’s 21% of the total amount paid by the state in capture contracts linked to the Guptas.

The third-highest earner was Neotel. Neotel was paid R5.581-billion by Transnet in relation to three contracts. That’s 9.78% of the total Gupta-linked State Capture tally.

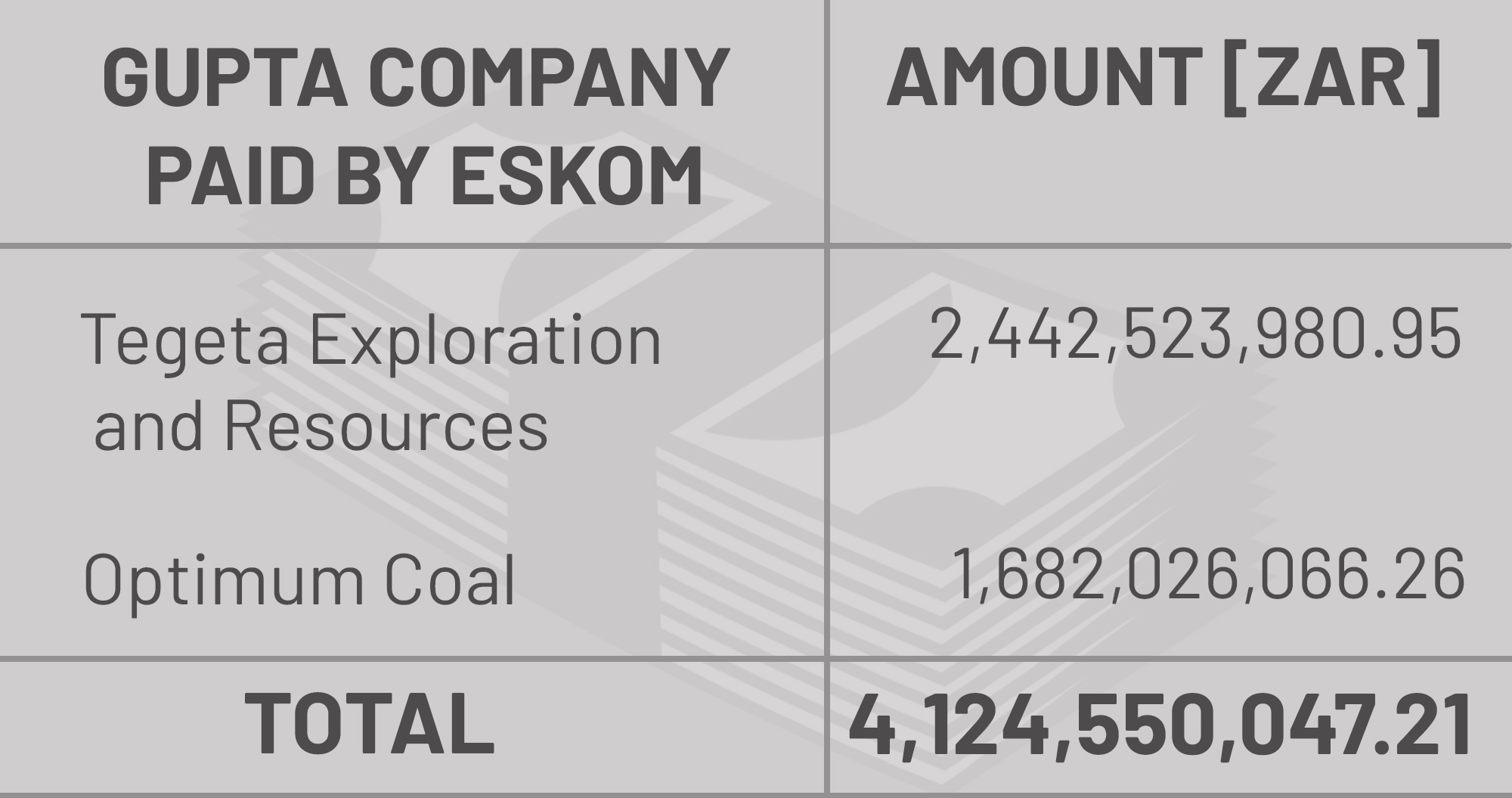

The fourth-highest earner was Tegeta Exploration and Resources (TER), the Gupta enterprise vehicle that held its mining assets. In total, Eskom paid TER R4,124,550,047.21. Of this, R2.4-billion was paid by Eskom directly to TER and the remaining R1.6-billion was paid to Optimum Coal after this asset was bought by the Guptas (using over a R1-billion from Eskom to do so, as I’ll discuss in later entries).

Coming in at fifth place is McKinsey, the multinational management consultancy firm. It earned R1,898,659,064.26 in total from contracts it shared with Regiments and Trillian; R784,287,306 from Transnet and R1,108,164,558.26 from Eskom. McKinsey’s income was 3.3% of all State Capture payments connected to the Gupta enterprise.

The primary sites of State Capture

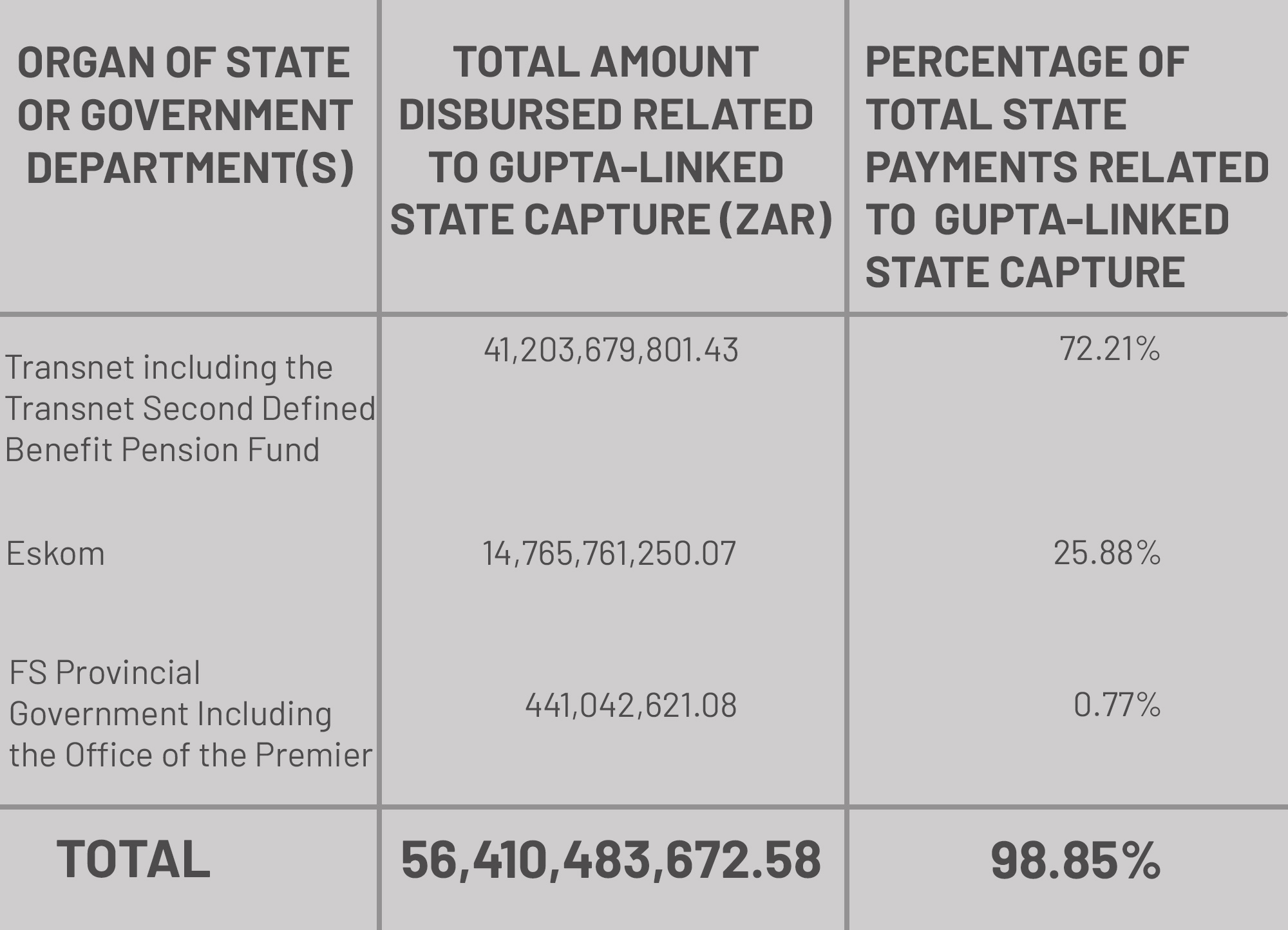

The three primary sites of State Capture, when measured against total State spend, were Transnet, Eskom and the Free State provincial government.

T-Systems and Eskom: A new mega contract tainted by State Capture

When I first presented my report to the Commission, I pointed out that I had seen that T-Systems had been making regular payments to a company called Zestilor starting in 2012, and suggested that the Commission identify the reason. T-Systems had paid R3,051,639.21 to Zestilor between August 2012 and mid-July 2015, 73.9% of Zestilor’s total income in that period.

While small in the grand scheme of things, the payments to Zestilor were particularly interesting because Zestilor was owned by Zeenat Osmany, who is married to Salim Essa, one of the Guptas’ key lieutenants. Essa was paid R501,010.10 by Zestilor between June 2012 and July 2015.

The discovery of the Zestilor payments led to another discovery: T-Systems had earned R7.8-billion through a nearly decade-long contract with Eskom that was closely linked to the Gupta enterprise.

T-Systems had first won the contract to supply IT services to Eskom in December 2009. This contract was supposed to run for five years, starting on 1 January 2010 and ending on 31 December 2015. But the contract never ended. Instead, it was extended, without competition, through a series of “modifications” – the most recent in June 2018 – that transformed a five-year contract to nearly double that length.

The repeated renewal of the contract was particularly strange as Eskom had attempted to cancel T-Systems’ contract and put it up for competitive tender. Letters from Eskom were sent to T-Systems on 26 August 2013 and 29 September 2014 making it clear that Eskom would not extend the contract and would put it out to tender. This never transpired.

On 24 June 2015, T-Systems global compliance monitor completed an internal compliance review. The compliance review was tasked with investigating T-Systems South Africa’s “non-IT consultancy agreements”.

Compliance Report by DocumentsZA

This review reveals that T-Systems opted to “informally” engage with Salim Essa (referred to as S.E) because T-Systems recognised that he “has a strong network to Eskom officials and stakeholders”.

T-Systems chose an “informal” route, rather than making Essa a formal consultant or agent, after it had started a compliance check. The compliance check included getting legal opinion on the “use of S.E. as a sales consultant – specifically the Prevention and Combating of Corruption Act”. The inference is that T-Systems quickly came to realise how problematic it would be to have Essa on-board formally, yet continued to engage with him and his allies “informally”.

Despite this, the compliance review concluded that “the decision to engage S.E. in an informal way and without any contractual basis led to a vast number of legal and compliance risks”.

The compliance report acknowledged that Essa’s “reward” for helping T-Systems with his “informal network” was that he introduced “several local and start-up companies to TSSA [T-Systems South Africa] decision makers and he requested TSSA to provide these companies with the opportunity to be included in the value chain where possible”.

No surprises for guessing who owned the “local and start-up companies” that T-Systems eventually included in its “value chain”. T-Systems made Sechaba Computer Systems its “supplier development partner” for the Transnet and Eskom contracts; the #Guptaleaks show that by 2015 it was controlled by the Guptas. Sechaba would ultimately earn R323-million as T-Systems supplier development partner.

The other “start-up” that made a fortune was Zestilor – the company controlled by Essa’s wife. Zestilor earned R238-million related to these T-Systems contracts. The bulk of this was earned when T-Systems agreed to cede the equipment rental portion of its contract with Transnet to Zestilor. Later, Zestilor would also be paid R75-million from Trillian.

Zestilor’s bank statements show it was largely a front for Sahara. Of R319-million paid to Zestilor in relation to the T-Systems and other contracts, 95% was paid onwards to Sahara Computers. Sahara was thus paid R302-million by Zestilor between May 2015 and September 2017.

The real kicker is how the T-Systems compliance audit ended. Despite the obvious quid pro quo between T-Systems, Essa and Gupta companies, the report concluded that the relationship between T-Systems, Sechaba and Zestilor was a “normal contractual relationship in place without any irregularities. There is no indication of corruption or any other illegal behaviour”.

And so, despite everything that would become known about Essa, Zestilor and Sechaba, T-Systems’ group compliance department gave T-Systems the green light to keep doing what it was doing.

Coming up next

In the next instalment, I will explain how the Gupta enterprise earned at least R16-billion from State Capture – creaming 28% from the total payments made by the state in cases involving the Guptas, and highlight some of the most egregious and lesser-known cases where the family made its mark. DM

Paul Edward Holden testifies at the State Capture Inquiry. (Photo: Gallo Images / Papi Morake)

Paul Edward Holden testifies at the State Capture Inquiry. (Photo: Gallo Images / Papi Morake)