Simon entered a political minefield: he transgressed the United Nations’ call to boycott the apartheid regime, he angered the ANC and other liberation movements and dared to question the thinking behind their political tactics.

This was the project, begun 35 years ago in February, that resulted in the release of Graceland, the album that saved Simon’s flagging career but also brought world acclaim for music from South Africa.

By no means ignorant of the horrors of apartheid, Simon appreciated the reasoning behind the cultural boycott, and had turned down invitations to perform at Sun City in what was then the Bophuthatswana “independent homeland”. Other famous musicians took up the invitation and came to play to white South African audiences who would never otherwise see world-class acts because of the cultural boycott. Many of these were blacklisted, including Queen, Rod Stewart, the Beach Boys, Frank Sinatra, Elton John and, crucially, Linda Ronstadt.

Around the same time, Steven van Zandt, guitarist for Bruce Springsteen, founded Artists United Against Apartheid, producing an album and single, both titled Sun City, to urge artists to support the cultural boycott. It featured Springsteen, Miles Davis, Bob Dylan, Herbie Hancock, Gil Scott-Heron, Ringo Starr, Run DMC, Lou Reed and Peter Gabriel among the 50 or so artists who took part. The single, released in December 1985, was moderately successful in the US but more popular elsewhere.

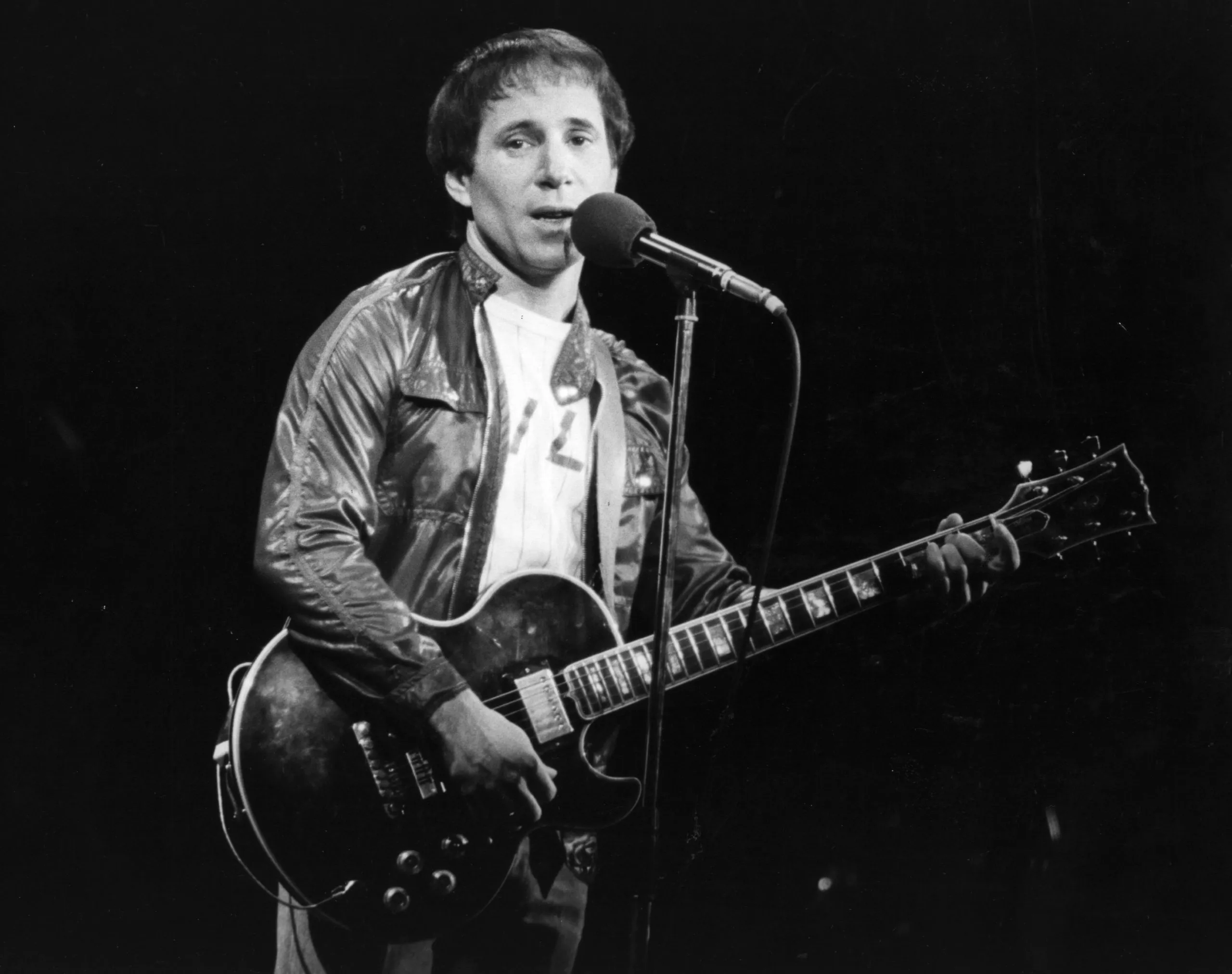

circa 1980: American pop singer and songwriter Paul Simon performing in London, during a series of solo concerts with a backing band and chorus. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

circa 1980: American pop singer and songwriter Paul Simon performing in London, during a series of solo concerts with a backing band and chorus. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Emergence from the depths of despair

Before Simon began the Graceland project he was at an all-time low. His last album, Hearts and Bones, was a commercial failure, the first time in his career that one of his records was ignored by the public and the only one not to go gold in terms of sales.

At 42, he felt he was unable to compete with Michael Jackson, Prince or Madonna, all the rage in the new MTV age. His marriage to actress Carrie Fisher had fallen apart after just a year, and he was deeply perturbed by his many negative experiences.

He spent much time sitting in his car, smoking joints for the first time in more than a decade, listening to music. He found himself listening to one tape in particular, Gumboots: Accordion Jive Hits, Volume II, a bootleg recording given to him by singer and songwriter Heidi Berg.

After making enquiries he got in touch with South African music producer Hilton Rosenthal, who was linked to Juluka and Johnny Clegg. The track Simon found haunting was by the Boyoyo Boys, mbaqanga veterans who had been making music since the early 1970s.

The music did something to Simon, who underwent a slow emergence from his depression, the South African music drawing him into a happier frame of mind and giving him the motivation to do something musically new.

He joined with other musicians in January 1985 to record We Are the World , a single to raise money for the famine-stricken people of Ethiopia, organised by Harry Belafonte and produced by Quincy Jones.

Simon approached Belafonte about his plan to travel to South Africa, and he advised Simon to talk to the ANC about the cultural boycott. According to Simon: “There were people who said I shouldn’t go. South Africa is a supercharged subject surrounded with a tremendous emotional velocity. I knew I would be criticised if I went, even though I wasn’t going to record for the government of Pretoria or to perform for segregated audiences – in fact, I had turned down Sun City twice. I was following my musical instincts in wanting to work with people whose music I greatly admired. Before going I consulted with Quincy Jones and Harry Belafonte, who has close ties with the South African musical community. They both encouraged me to make the trip.”

But he didn’t speak to the ANC and he didn’t tell Belafonte when he made the decision to come to South Africa. He did, though, take this advice from Quincy Jones seriously: “Just be sure everybody gets paid and that everybody likes you.”

Joburg, Soweto, a time of emergency

Simon arrived in Johannesburg with recording engineer Roy Halee and was shocked by the racial tensions in the country. This was in February 1985, about six months after the beginning of the Vaal Triangle uprising in September 1984, which would become the final wave of resistance that prompted the state of emergency in 1986, and which ultimately resulted in the demise of apartheid.

Before Simon left for Johannesburg, Rosenthal had contacted Koloi Lebona, a producer, to bring together the musicians Simon was interested in playing with.

Some of these musicians were eager to play with Simon, but not all of them. The Soul Brothers, supporters of the ANC, passed on the opportunity, having been advised by the ANC to reject Simon’s overtures.

Simon spent a frantic two weeks in South Africa. He jammed with the musicians at a studio, recording hours and hours of music that would eventually be reconfigured into the album. Unlike his previous work, where songs were constructed before he went into the studio, here he improvised, letting the musicians play and listening out for interesting ideas and snippets that could be turned into complete works. Unwittingly, he was laying himself open to the charge of cultural appropriation.

Some musicians addressed Simon as “Sir”, observing the norms of baaskap. And they were anxious to finish by 5pm so they could get back to the townships, in keeping with pass and curfew laws. But they soon relaxed into joyous music-making.

The Lesotho group Tau Ea Matsekha introduced Simon to Forere Motloheloa, who worked on the mines, and the accordion player provided the flourishes that would open the album.

Simon was impressed by the drumming of Vusi Khumalo, which reminded him of the groove on Elvis and Johnny Cash recordings. Bass virtuoso Bakithi Kumalo, who was working as a mechanic, hadn’t heard of Simon when approached by Lebona, but he recognised Mother and Child Reunion when the producer sang the song to him. His bass lines would be a distinguishing feature of the album.

Chikapa “Ray” Phiri played a progression that would become the basis of You Can Call Me Al, the biggest hit from the album. The track Graceland began with a drum track from Khumalo, with Phiri putting a guitar lick to it that surprised Simon. It had a minor chord in it, which South African music didn’t generally use. When he asked Phiri about it, the guitarist said he’d been listening to Simon’s records and frequently came across that type of sequence. Simon was pleased: it meant a coming together of two worlds both listening to each other.

Simon was soon introduced to Ladysmith Black Mambazo, the now renowned isicathamiya group founded in 1960. Its leader, Joseph Shabalala, was very quiet in the studio, even “mysterious”, according to Simon. Shabalala was shocked when Simon hugged him, while Simon was “bewitched” by the Zulu choir’s music, as the world would be later.

The Boyoyo Boys, veterans of the mbaqanga genre, were too nervous to perform at first, and the white engineers said it couldn’t be done, but they were proved wrong.

General MD Shirinda and the Gaza Sisters contributed the Shangaan guitar and the hysterical, almost dissonant yet delightful female vocals to I Know What I Know, one of the quirkier tracks on the album.

Eventually the core group consisted of Bakithi Kumalo, Ray Phiri and drummer Isaac Mtshali. Contributions were made by a string of musicians, including Barney Rachabane and Mike Makhalemele.

The album’s reception – and awards

Simon says he named the album Graceland because it represents a process of healing: “It seemed to be about finding something you could call a state of grace – the healing of a deep wound. And that’s what was going on in South Africa. There was a deep wound, and then an attempt at a healing process.”

In New York he invited contemporary composer Philip Glass to listen to parts of Graceland and advise him. Glass recalled: “I went over to his apartment with my wife, and he played a song, and, as he often does, he started singing the words over the music. I thought it was amazing. I said, ‘Paul, this is a real breakthrough. It’s going to be a masterpiece!’ ”

In May 1986, before the album was released that August, Simon flew the South African musicians to New York, first class, to appear on Saturday Night Live. They performed Diamonds On The Soles Of Her Shoes, and the audience was ecstatic. SNL producer Lorne Michaels enthused: “It was the synthesis of two cultures… and the obvious affection they had for Paul, and that Paul had for them… It was the perfect moment.”

Warner Bros executives, who had written off Simon as a has-been, were bewildered when the album was played to them, although they sent out rumours that they went wild listening to the music. They must have been even more confused by the global public response to the album. It was a massive hit, remaining on the charts for 97 weeks. It won the Grammy for Best Album in 1987 and many other accolades. It sold about 16 million copies, and Simon regards it as the peak of his career.

The music is South African, the lyrics very New York, and Graceland was not planned as part of the album’s theme, but Simon ended up making an album that was a hybrid of disparate elements. Indeed he struggled to create a unity out of the various themes, genres, styles and whatnot, a process that necessitated an interminable process of editing.

Even acclaimed Caribbean poet Derek Walcott, who Simon had met around that time, was impressed, saying: “Mostly, songwriters try to be clever, and that’s not the same as poetry.” According to Robert Hilburn, in his biography, Paul Simon: “However, he [Walcott] felt that much of Simon’s work contained the discipline, grace, and truthfulness of poetry, and he cited the opening lines of Graceland as evidence, describing them as ‘pure poetry, Whitmanesque’.”

The Graceland Tour

Simon toured extensively in 1987 after releasing the album, meeting as much acclaim as hostility.

In early 1987 the UN had placed Simon on its list of those who had violated the cultural boycott. Before the tour began he was given a sort of idiot’s guide to South African politics by Johnny Clegg. He held a press conference and read out a letter he had written to the ANC and the UN Special Committee Against Apartheid. But when the committee described the letter as an apology, Simon became defiant, and he was once again the object of criticism. But he was saved by Alan Boesak and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who weighed in on his side.

Simon roped in Hugh Masekela, who brought in Miriam Makeba, reinforcing the notion that this was not a project that would in any way exacerbate apartheid inequalities, and would instead bring the people of the world to a greater appreciation of the South African situation, and take the country’s culture to a global audience.

There were protests outside many venues, with placards accusing him of stealing music from poor black musicians, typical of colonial extraction. In the US he was confronted by black activists who refused to acknowledge that he could work with the black South Africans as equals. At the Albert Hall in London, too, there were protesters.

The tour ended with a massive concert in Harare, Zimbabwe, where Makeba led a rendition of Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika. Thousands of South Africans had travelled to the country to attend the concert.

Paul Simon performs the album 'Graceland' live on stage during the third day of Hard Rock Calling at Hyde Park on July 15, 2012 in London, England. (Photo by Jim Dyson/Getty Images)

Paul Simon performs the album 'Graceland' live on stage during the third day of Hard Rock Calling at Hyde Park on July 15, 2012 in London, England. (Photo by Jim Dyson/Getty Images)

Yet more controversy

Musicians are always enmeshed in relationships that are productive but which also lend themselves to conflicts about intellectual property, with collaborators often claiming they were not given the credit due to them.

Simon’s collaborations with South African musicians seems relatively free of such resentment, perhaps a rare example of a successful collaboration good for most of those involved.

Phiri appears to be the only musician who complained of being exploited. While Joseph Shabalala, General Shirinda, Forere Motloheloa, Lulu Masilela and Jonhjon Mkhalali of Boyoyo Boys are credited as co-composers of tracks on the album, Phiri is not, even though Simon admitted that You Can Call Me Al was based on the guitarist’s chord progression. So perhaps Phiri was not merely being resentful when he complained that he had not been credited as a writer. Nevertheless, he had this to say some time before making the accusation: “We used Paul as much as Paul used us. There was no abuse. He came at the right time and he was what we needed to bring our music into the mainstream.”

Simon was accused of stealing the music of Los Lobos and also of Good Rockin’ Dopsie and the Twisters, but he later opined that all musicians take from each other, in a process natural to music. Indeed, Simon himself had stolen the idea of a South African album from Heidi Berg, who had given him that tape by the Boyoyo Boys, and she too accused him of stealing an idea which had been hers in the first place.

Linda Ronstadt’s contribution to the song Under African Skies was another cause for controversy. She had played Sun City in 1983, and her inclusion on the album was seen as a further snub to the anti-apartheid movement. Simon defended her, saying she had not been aware of the nature of South African politics when she toured the homeland. For this he was castigated by American critics.

More seriously, he had offended the Azanian People’s Organisation, which was much more militant than the ANC, and placed on their hit list. Strangely, it was Steve van Zandt who dissuaded the Azapo militants from “neutralising” him.

It took Nelson Mandela to rehabilitate Simon in the eyes of some of the liberation movements. In 1992, the revered statesman invited Simon to perform in South Africa, with the backing of the ANC. Simon obliged with a series of concerts, which were organised by promoter Attie van Wyk. But the Azapo militants were stewing at the move, and members of their youth wing tossed grenades into Van Wyk’s offices, destroying the premises.

A reunion and anniversary

A well-researched documentary recorded the 25th anniversary of the album and Simon’s return to South Africa in 2011 to reunite the musicians of Graceland. The documentary, Under African Skies, was first aired in 2012. It charts the history of the project, its controversies and the reunion.

It features an encounter between Simon and Dali Tambo, one of the founders of Artists Against Apartheid, the two conversing about their views of what had happened. Simon sets out his case, followed by Tambo, and the pair argue back and forth about the issues.

The reasoning behind the cultural boycott, as set out by Tambo, was this: artists who came to South Africa were lending legitimacy to the regime, and exceptions could not be made to the boycott call, as this would have become an invitation to apply to the ANC to break the boycott. Simon argues that there was a distinction to be made between those playing with South African artists and those performing in segregated venues.

When Simon pointed to the manner in which the musicians had benefited from the project, Tambo averred that the ambitions of a few musicians could not be deemed more important than the fate of an entire nation.

But they arrived at a kind of peace deal, and at the end of their talk they embraced, and Simon could finally rest easy about all the issues that had simmered for so many years.

Aftermath

Phiri went on to play on Simon’s next project, Rhythm of the Saints, and had been a successful musician even before his Graceland stint, leading one of South Africa’s leading bands, Stimela. His life was marred by various car accidents, in one of which his wife died. He died in July 2017 at the age of 70, after being awarded the Order of Ikhamanga in Silver for his services to music and the arts. Despite his remark that there had been “bad blood” between him and Simon, he concluded that if it had been different, “maybe I wouldn't have been able to handle all that wealth. I sleep at night,

I have my sanity and I enjoy living. The big rock ‘n’ roll machine did not munch me.”

Shabalala considered Simon as a brother, and their collaboration led to Ladysmith Black Mambazo achieving immense acclaim throughout the world. The group went on to win five Grammy Awards, later working with George Clinton and Michael Jackson, among others. He died in February 2020 at the age of 79.

Some of the original band have since passed away – Mtshali in August 2019 and Makhalemele in 2000 – but Rachabane is still blowing his horn.

In February 2018, Simon announced that he would retire from live performances after a final set of concerts in the US and Europe. DM/ML

LONDON, ENGLAND - JULY 15: Paul Simon performs the album 'Graceland' live on stage during the third day of Hard Rock Calling at Hyde Park on July 15, 2012 in London, England. (Photo by Jim Dyson/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JULY 15: Paul Simon performs the album 'Graceland' live on stage during the third day of Hard Rock Calling at Hyde Park on July 15, 2012 in London, England. (Photo by Jim Dyson/Getty Images)