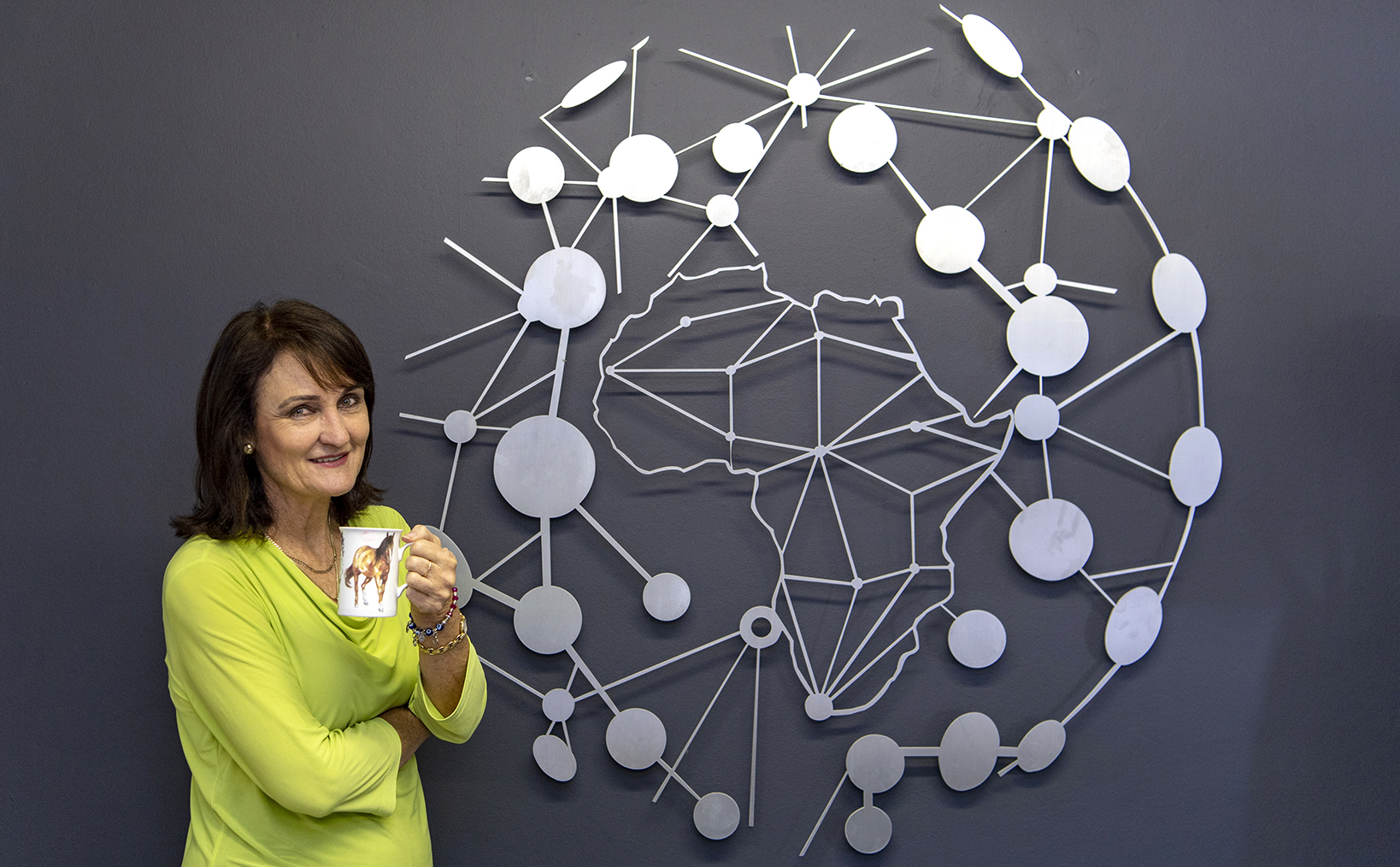

Professor Petro Terblanche, the managing director of the biotechnology company Afrigen was sitting in her office in Montague Gardens, Cape Town on a sunny day in January when she got a visit from the head of her technical team.

After four months of hard work, the team had successfully completed the first step of making an mRNA vaccine for Covid-19. They had got the genetic coding into its carrier — a lipid nanoparticle.

Recalling the day she received this news, Terblanche says, “The analytical data looked so beautiful that I jumped up and down.”

Managing Director of Afrigen, Prof Petro Terblanche. (Photo: Gallo Images / Die Burger/Jaco Marais)

Managing Director of Afrigen, Prof Petro Terblanche. (Photo: Gallo Images / Die Burger/Jaco Marais)

By February, a month later, the next set of results was in. These were from mouse studies that showed that Afrigen’s vaccine candidate elicited an immune response. And with that, the company became the first on the continent to make an mRNA vaccine from scratch. (Spotlight previously reported on the science involved here.)

“I knew then nothing will stop the team,” Terblanche recounts while sitting in that same office with a silver cut-out of the Afrigen logo behind her.

A farm girl at heart

The cutting-edge work that Terblanche is now involved in is a far cry from the farm where she grew up as a child.

On a bookshelf in her office, there is a statue of four horses — each representing a different element: water, earth, fire and air. But she prefers to spend her time with the real animals and on alternate weekends she makes the trip from Cape Town to Pretoria to spend time on her farm with her own herd of more than 60 horses.

“I’m a farm girl at heart. I’ve always been a farm girl,” she says.

Terblanche grew up on her family’s farm in Brits in North West — an hour’s drive from Pretoria.

“I grew up on a very basic, rural farm, but it never felt like I was not cared for or that I didn’t have enough. One pair of shoes for church and one for school was more than enough.”

Professor Petro Terblanche loves horses.

Professor Petro Terblanche loves horses.

(Photo: Supplied / Spotlight)

Between children at the neighbouring farms and her cousins, Terblanche spent her free time hanging out with boys.

“I grew up roughly [among] about six boys and I did everything they did. I rode the cattle, rode horses, and climbed trees. I was barefoot and hated dresses. When they started boxing lessons, I was six years old, and I also joined in.”

Her upbringing fostered a deep love of nature and animals.

“I worked the land, I drove the tractor, and I worked the soil. I really love the earth. When I got to matric, I told my dad that I was staying to farm with him.”

Her dad, however, had other plans and despite her tears over the prospect of leaving, he insisted that she go to university. She followed through but didn’t want to leave her passions behind, so she completed a degree in zoology and botany at the University of Pretoria.

‘Doing something that means something’

For her honours degree research project, Terblanche chose to study the chemical reactions that allowed animals to become nocturnal. That’s when the boredom began to creep in.

“I came down to the lab, and it was one of those days that I had to analyse another 40 mouse livers and I thought, ‘Who the hell cares? I can’t do this any more. I want to do something that means something, I want to do something that has high impact.’ ”

Rather fortuitously, an advert on the wall of the lab caught her eye. They were looking for research officers in the oncology department. Despite having no health sciences background, Terblanche went for the interview and secured a position.

“I started all over again,” she says. “I had to learn from basics. So, the first thing I did was ask for permission to attend medical school.”

Terblanche’s new routine meant her days were split between her research work and squeezing in classes wherever possible, including in the evenings. Within two years she had completed her master’s thesis on lymphoma. Getting the actual degree, however, turned out to be a bit more complicated.

Terblanche laughs as she recalls. “At that time, there was no such thing as a master’s degree in health sciences for medical oncology. They had to give me the degree in zoology, so it’s a complete misnomer. If you look at my thesis, it is a health sciences thesis, but my degree is in zoology.”

Never one for rest, Terblanche immediately dived straight back into studying and went on to get her doctorate in 1987. She’d been working in the oncology department for four years by that point, and it was beginning to take a toll.

“I worked on childhood leukaemias and had many patients dying in my studies,” she says sombrely. “I saw… I saw… I saw death.”

Terblanche remembers sitting down with her father to discuss what her next steps should be. She was planning to remain with the department and continue her work, but he worried that it was making her “very serious”.

“I did become more serious,” she says. “I became very reflective. And then I decided maybe it’s time to change.”

New frontiers of science

Always looking for a new challenge, Terblanche decided to leave oncology and make yet another unprecedented move. She entered a completely new field at the time — air pollution epidemiology — also after seeing an advert. The SA Medical Research Council (SAMRC) was creating a new Institute of Environmental Diseases and was looking for scientists.

She landed the job.

Terblanche also secured a postdoctoral fellowship (a position that allows people to continue training and learning after completing their PhD) at Harvard University in the US. When she returned to South Africa in 1990, Terblanche took on what would become groundbreaking work through the Vaal Triangle Air Pollution study. The research was intended to last 10 years and would look at the impact of industrial air pollution on children’s health.

The study was the first of its kind in many ways. It was the longest research project in South Africa to look at the health impacts of air pollution at the time. It was also the first time Terblanche had taken control of a scientific investigation from beginning to end — from the project design to securing funding, and managing the team that carried it out.

“It was pioneer work,” says Terblanche. “It was the first time in the history of South Africa that we monitored children’s personal exposure and what they were breathing in — both indoors and outdoors.”

Terblanche fondly recalls how proud the 10,000 children involved were to don their monitors, which tracked air pollution levels, once the study officially began. But once the results started to come in, she was in for a huge shock.

“I knew the air pollution in those areas was bad, but I didn’t know how bad.”

A worker in a supply store at Afrigen laboratories, the World Health Organization, Vaccine Hub in Cape Town. (Photo: Rodger Bosch / MPP / Spotlight)

A worker in a supply store at Afrigen laboratories, the World Health Organization, Vaccine Hub in Cape Town. (Photo: Rodger Bosch / MPP / Spotlight)

They found that the pollution levels in Sebokeng, a township near Vereeniging in Gauteng, were higher than those during the Great Smog of 1952 in London, which led to the deaths of up to 12,000 people.

“The exposure levels that people in townships were enduring was horrific.”

By the halfway point of the study, she decided they had enough data to end the project. The decision wasn’t without controversy. Terblanche faced criticism for ending the research early but felt it was the right call.

“I felt we knew enough to influence policy decisions,” she says. “Instead of spending another R5-million to get a few more publications and collect more data, I’d rather use that money on interventions and putting things into action.”

And that’s what she did.

Terblanche and the team dedicated their time to raising awareness about the impact of air pollution on these communities, which ultimately led to changes in South Africa’s legislation on this issue, including the National Environmental Management Act 107 in 1998 and its amendment — the Air Quality Act 39 of 2004.

“I don’t do science for science. I do science for change,” she says.

‘Show me how much you care’

After wrapping up the five-year study, Terblanche became the director of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) from 1995 to 2004 — the first woman appointed to this position.

“I don’t think I’m a good scientist, because I lean more towards people,” Terblanche says. “I’m more of a manager or a leader than a scientist. But scientific knowledge and processes intrigue me. I find myself embedded in the science, but I don’t do it.”

Her time at CSIR opened Terblanche’s eyes to a whole new side of research — and it started with a cactus.

Hoodia gordonii is a cactus-like plant that grows in the Kalahari Desert. It has also been used for centuries by the San people. They would chew on the prickly plant during long hunting trips to help reduce their hunger.

The CSIR began looking into Hoodia in the 1960s and 30 years in, when Terblanche was heading the unit, they isolated and named its active ingredient, P57. Some researchers at the organisation believed at the time that it could be used as an appetite suppressant and marketed as a potential weight-loss drug (hopes that would later be dashed by the drug’s toxicity). One problem, however, was that this work didn’t acknowledge the role the San people played in identifying these properties in the plant.

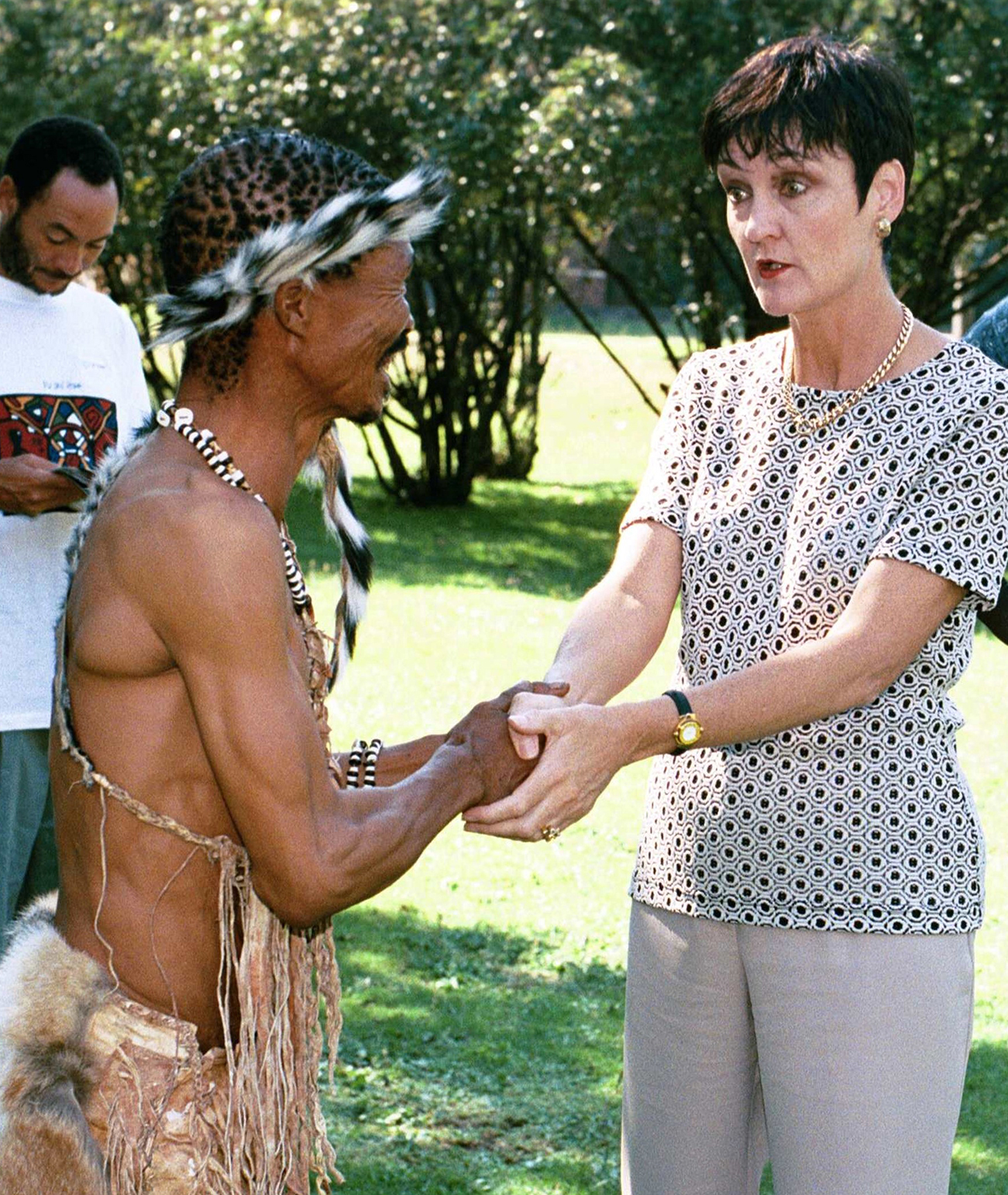

Professor Petro Terblanche during a meeting with Petrus Vaalbooi, the leader of the Khomani San people. (Photo: Supplied / Spotlight)

Professor Petro Terblanche during a meeting with Petrus Vaalbooi, the leader of the Khomani San people. (Photo: Supplied / Spotlight)

“The San people have thousands of years of using these plants and they have learnt the properties by sacrificing lives,” she says, stressing her respect for indigenous knowledge. “Information from the indigenous space was used to trigger this research but there was no structure —there was no real policy on how to recognise that.”

She remembers calling up the CSIR president one evening to discuss if there was a way to fill this policy void. However, the advice relayed back to her she says was: “No. You will not talk to those people.”

Terblanche chose to ignore that instruction and set up a meeting with Petrus Vaalbooi, the leader of the ‡Khomani San people.

“It was one of the most emotional moments of my life,” Terblanche recounts. Vaalbooi arrived at the meeting in traditional San clothing, with a piece of animal hide wrapped around his waist, while Terblanche wore beige trousers with a black and white patterned shirt.

“He greeted me and said something I will never forget. He said, ‘I don’t care how much you know until I know how much you care. You are the doctor, but I want to know whether you care before I talk to you.’ ”

It wasn’t an overnight process and not without controversy. But by 2003, the San people and the CSIR had successfully reached one of the world’s first benefit-sharing agreements. The deal meant that the role of the San people in the knowledge generation was not only explicitly credited, but the community would also get a share of any money made off P57 products.

Terblanche looks back on the experience fondly. “The drug didn’t make it to final approvals because of toxicity, but it was a wonderful journey. It was a very enriching journey for scientists at the CSIR and for myself.”

The culmination of a career

After leaving the CSIR, Terblanche took on several other managerial roles in the SAMRC, the South African Nuclear Energy Corporation, and then Pelchem, a chemical manufacturer in North West.

And then came the big one.

“Three years ago, I was approached to head up this little start-up, Afrigen,” she remembers. Little did she know that a major epidemic was about to hit the world and that the “little start-up” would end up making headlines around the world for developing an mRNA vaccine without the help of the big pharmaceutical companies who first brought mRNA vaccines to market.

“The last 18 months, since the mRNA hub project was launched, was the one job in my life that draws on everything I’ve learnt before. Everything,” she says.

Professor Petro Terblanche during a site visit to Afrigen by World Health Organization director-general, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and Belgian Minister for Development Meryame Kitir. (Photo: WHO / Spotlight)

Professor Petro Terblanche during a site visit to Afrigen by World Health Organization director-general, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and Belgian Minister for Development Meryame Kitir. (Photo: WHO / Spotlight)

Back in her office, there is a gold “Oscar” statue on the shelf that her team awarded her with the epithet of “the nutty professor”. It’s a title that Terblanche gladly accepts.

The work is of course far from over. “If you look at what’s happening now with the mRNA hub — we’re designing and making a vaccine,” she says, “but we’re also driving policy — policies around access, manufacturing, sustainability, intellectual property.”

The vaccine work she’s doing now has also given Terblanche the opportunity to move more into an advocacy role, with her time now being dedicated to ensuring equitable access to vaccines in lower- and middle-income countries.

“Advocacy for me is such an important output of research and of technology,” she says. “It’s a people’s process. It’s not a data process, it’s not a machine. It’s about people. If you asked me today what is it that brings the joy and rewards to any job that you do — it’s the teams that you build around you. It’s the people component.” DM/MC

This article is part of Spotlight’s 2022 Women in Health series that was running throughout August

This article was published by Spotlight — health journalism in the public interest.

Professor Petro Terblanche during a site visit to Afrigen by World Health Organization director-general, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and Belgian Minister for Development Meryame Kitir. (Photo: WHO / Spotlight)

Professor Petro Terblanche during a site visit to Afrigen by World Health Organization director-general, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and Belgian Minister for Development Meryame Kitir. (Photo: WHO / Spotlight)