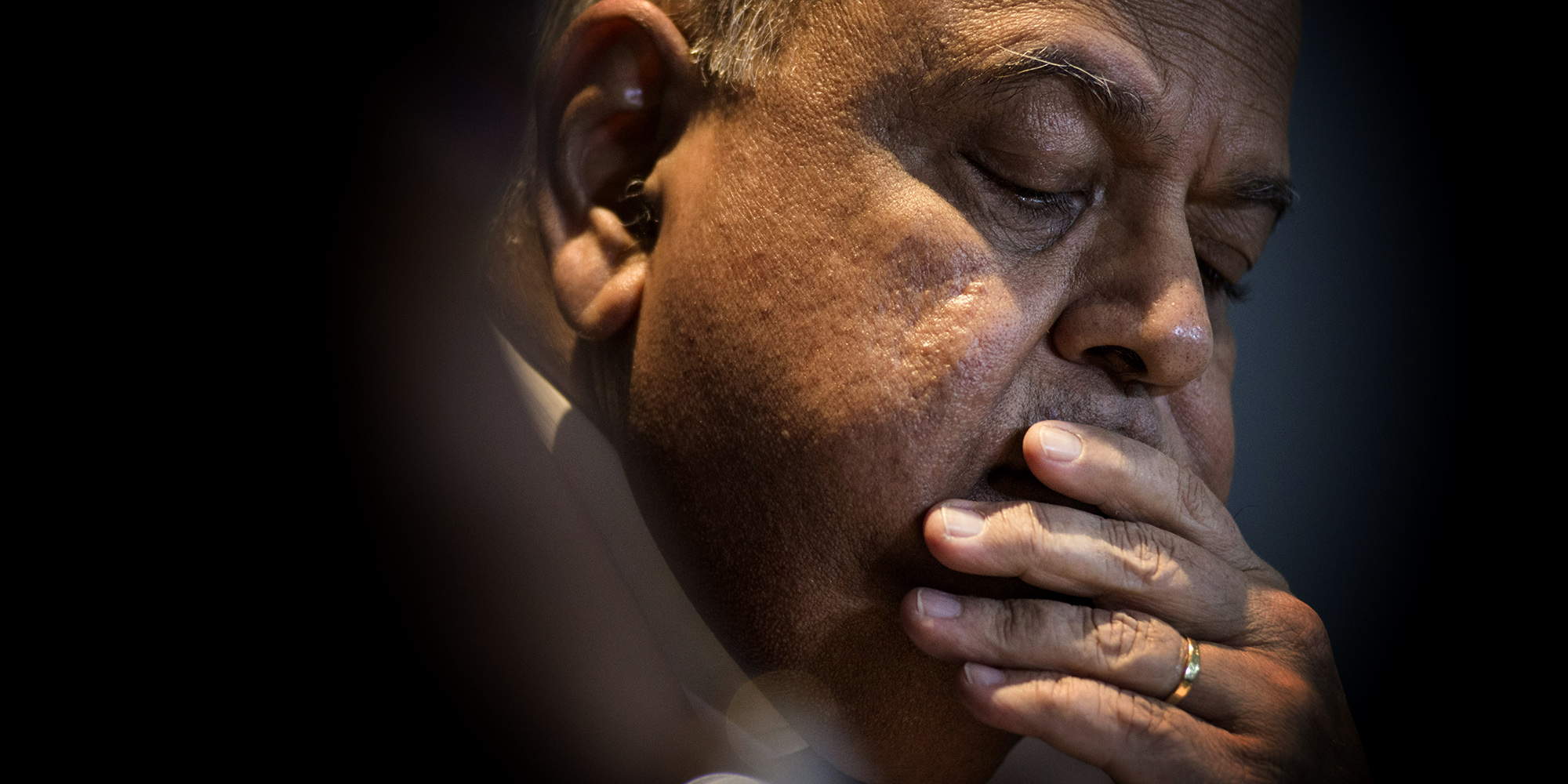

While he was hugely popular with the middle classes as the most visible public symbol of ANC resistance to then president Jacob Zuma, Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan’s image has changed significantly since those dramatic days.

It’s difficult now to remember how important Gordhan was in the fight within the ANC, in the congress movement and in society generally to remove Zuma from power.

After Zuma overreached by removing Nhlanhla Nene as finance minister in December 2015, the rand lost value overnight, shares on the JSE fell off a cliff, and the ANC famously failed to congratulate Nene’s successor Des van Rooyen.

Just hours before markets were due to open in Asia on the Monday morning following Van Rooyen’s appointment, the ANC went into damage-control mode. As it is now understood, Zuma was convinced by ANC leaders that Van Rooyen could not stay in office and there was an urgent search to find someone who could calm the markets.

In the end, it was then Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa who phoned Gordhan to ask him to take the post.

In the months after that, it became obvious that Zuma was persecuting Gordhan. Zuma’s agents in the Hawks and the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) charged Gordhan with fraud (even the NPA head at the time, Shaun Abrahams, realised the charges could not stand up), and tried to limit his movements.

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2016-10-18-analysis-dizzy-days-at-state-capture-central/

When Gordhan was fired in March 2017, there was outrage. The SA Communist Party said it wanted Zuma out of office, Ramaphosa publicly objected to the decision, and then ANC secretary-general Gwede Mantashe said the new Cabinet was a “list that’s been developed somewhere else” in what was widely interpreted to mean the Guptas’ home in Saxonwold.

For the first time since the advent of democracy in South Africa, middle-class people joined protests, to defend their interests and a man they saw as their hero, Pravin Gordhan.

Much has changed since then.

Now, Gordhan is sometimes portrayed as a major cause of the problem and criticised by the right and the left.

While trying to assess how and why this has happened, it should be noted that because of the problems facing SA’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs), anyone who was minister of public enterprises now would be in the centre of a storm.

Weakening of state power

One of the most important dynamics of this has been the trend towards a bigger role for the private sector, with its accompanying weakening of state power.

This was always going to be hugely contentious and led the ANC Youth League to claim that “one day we’ll wake up and hear that South Africans have been sold to another country” by Gordhan.

Gordhan, the ANC and Ramaphosa himself have all denied the party is following a policy of privatisation.

However, for most people, the only metric that matters is how services they rely on SOEs to provide have declined since Gordhan was appointed.

Of this, there can be no doubt.

Eskom recently announced its highest number of days of load shedding yet and its biggest loss.

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2023-10-31-eskom-posts-record-r23-9bn-financial-loss/#:~:text=Eskom%20made%20a%20whopping%20R23,R11.9%2Dbillion%20loss.

Last week, Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana said that Transnet had simply ticked the boxes when it came to implementing a decision to allow private companies to use its railway tracks. The company is failing to move goods to the coast, with the result that SA’s entire economy has lost out.

Meanwhile, Gordhan is claiming important progress at SAA.

He cited as proof of its recovery the fact that it was reinstituting flights to São Paulo. But, as has been pointed out by aviation analyst Phuthego Mojapelo, it is not clear that there is a business case for flying to Brazil, especially directly from Cape Town.

Given SAA’s history of flying uneconomical routes for political reasons (and in one case, Malusi Gigaba’s apparent support for SAA to stop flying a profitable route to India so the Guptas’ friend’s airline could benefit), many will not take political promises at face value.

The laborious Takatso deal

There is still no certainty on why the Takatso deal is taking so long.

It was first announced more than two years ago, and while there have been some issues with shareholders, it still makes no sense that the deal has not been completed.

This will give ammunition to those who believe Gordhan is trying to frustrate the deal, even though there is no public evidence of this.

There is even less transparency with SAA’s low-cost airline, Mango.

The business rescue practitioner in charge of the company, Sipho Sono, has gone to court because Gordhan refused to decide on whether to sell the airline.

When a judge ruled that Gordhan must make a decision, he appealed against the verdict.

To be clear, Gordhan is not appealing against a decision about whether the government must sell the airline. He is appealing against a judgment that he must make a decision.

Sono says that Gordhan “wants to see the business case of the selected investor” before making a decision. Sono won’t share this information because he does not want it to be seen by SAA, a possible competitor of Mango Airlines.

He described Gordhan’s decision to appeal against the ruling as “strange”.

Actions at Eskom

But the word “strange” does not do justice to Gordhan’s actions at Eskom.

While he did condemn Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe’s claim that former Eskom CEO André de Ruyter was trying to undermine the government through load shedding, this support was not enough for De Ruyter to stay in his job.

But, more importantly, he has prevented Eskom’s board from appointing a new CEO.

As News24’s Carol Paton reported in September, the Eskom board sent Gordhan the name of its preferred candidate in May. Three months later (at least), he rejected the candidate, on the grounds that the board should have sent him three names from which to choose.

The consequence of this decision is that Eskom still does not have a CEO. And it was surely the case that his decision to wait so long before rejecting the candidate was based on politics, or the fight for control, which also led to Mpho Makwana’s resignation as Eskom chair.

Gordhan too must have played a role in the resignations of Transnet CEO Portia Derby and other senior executives at the SOE.

Just weeks before their resignation, he told Transnet’s board it had three weeks to create a turnaround plan for the SOE. He also oversaw Derby’s appointment in January 2020.

At the same time, Gordhan may be defying the ANC in how he wants SOEs to be run in the future.

He has published a draft bill that would see SOEs being controlled through a single holding company. However, the ANC decided at its conference last year that SOEs should go back to their line departments, so, for example, Eskom would be under the Energy Ministry.

Again, this is a strange decision, particularly since the holding company model has been so strongly criticised.

Overall SOE chaos

All these moves and the overall SOE chaos have changed the prism through which Gordhan was seen — from the hero who took on a corrupt president, to a minister making strange decisions that have a negative impact on the entire country.

However, it should also be remembered that governance in South Africa is always difficult, and now more so than ever. The political journalist John Matisonn once observed that none of our presidents has been a Cabinet minister. While some were deputy presidents before becoming president (Kgalema Motlanthe did it the other way round), they have never had a ministry to run.

This may be because running a ministry in this environment will alienate certain constituencies and any minister who runs an important Cabinet department during a crisis is directly in the line of fire.

That said, Gordhan must take responsibility for the decisions he has made. While he has a difficult job, the fact is that he is the one who rejected Eskom’s choice for CEO, oversaw Derby’s appointment (and resignation), and made decisions at Mango Airlines that were described as “strange”.

By default, the SOE minister’s mistakes affect every South African. His public image has changed dramatically over the past six years and history’s judgement of his legacy will have to take these post-2017 years into account. DM