The stories in the collection made me pause. They slowed me down. And days later, I was still carrying them with me, not as a collection, but as a conversation that hasn’t quite finished.

Maybe that’s the magic of it: Call and Response doesn’t end. It waits for you to answer back.

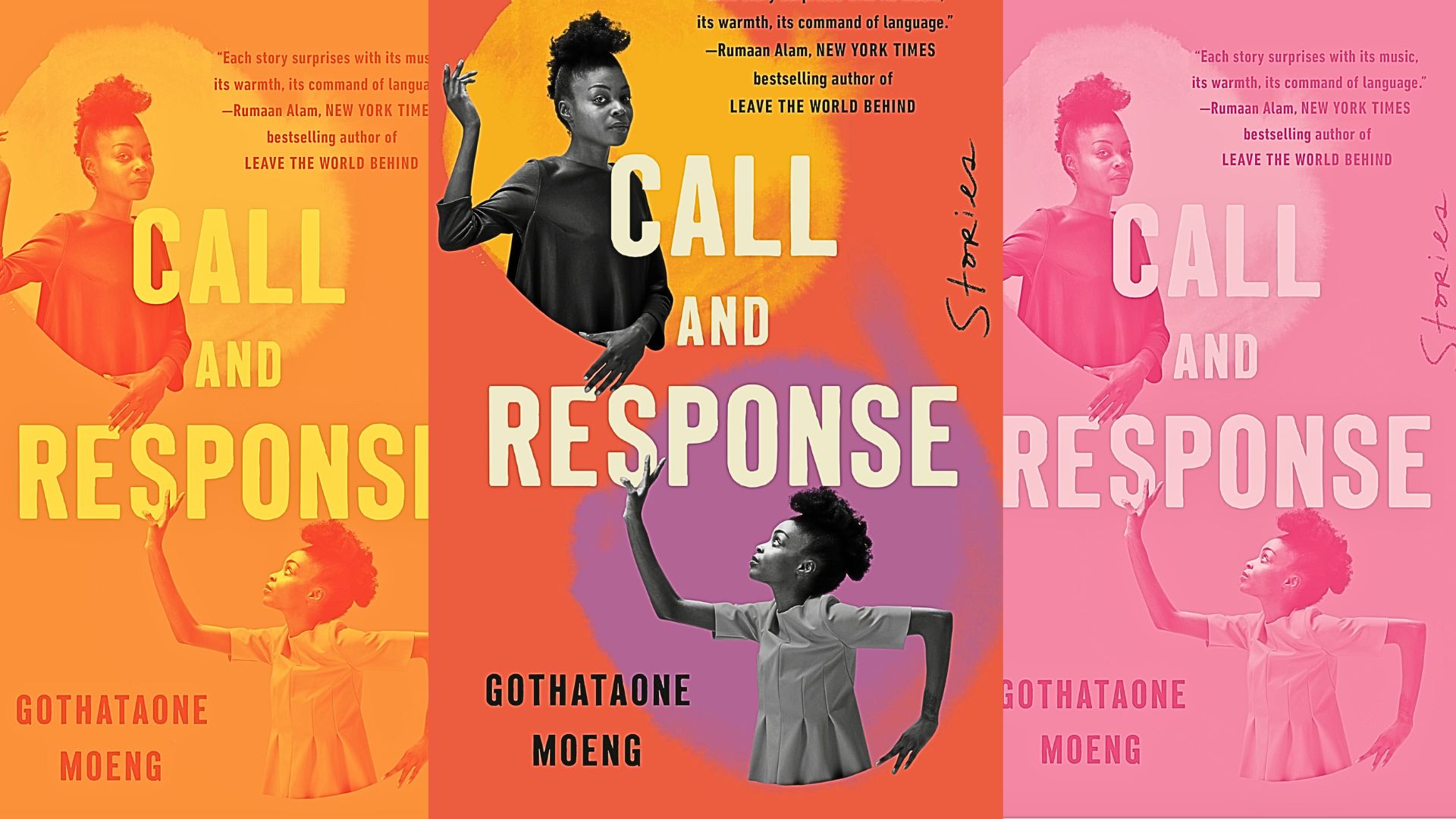

Gothataone Moeng’s debut story collection moves between the quiet rhythms of Serowe, a rural village in Botswana, and the restless energy of its capital, Gaborone.

Across 11 stories, we meet women navigating the tension between tradition and modernity, desire and duty — each caught in the subtle push and pull of expectation and selfhood.

“I write about women who find themselves pulled in two directions — duty and desire,” Moeng told me.

Call and Response resists the trap of resolution in the telling of the stories. Instead, Moeng captures the complexity and simplicity of everyday life — its quiet contradictions, unresolved tensions, and moments that linger not because they flare, but because they settle and stay with you.

Her portrayal of women’s lives is both deeply specific and widely resonant, drawing out themes of love, familial duty, and the quiet negotiations of self-sacrifice.

Not initially a book

“I didn’t set out to write a book,” Moeng shared. “I was just writing individual stories, and then at some point they started speaking to each other.”

That slow accumulation — the rhythm of reflection, and repetition — gives the collection its quiet power. The title itself draws from African storytelling traditions.

Moeng explains: “There’s always a call. A cry. And there’s always someone, or something, that answers. Maybe not always in the way we expect, but it comes.” What began as isolated stories eventually revealed a quiet dialogue between them, a narrative call and response that mirrors the oral storytelling traditions Moeng draws from. Each piece echoes the others, creating a subtle rhythm across the collection where themes resurface, shift, and deepen through repetition and return.

The emotional geography of Serowe

The collection is deeply rooted in place. Whether in Serowe or Gaborone, Botswana is not a backdrop but a living emotional geography.

“Reading Bessie Head gave me permission,” Moeng says, “She gave me permission to write about people from where I’m from. Before that, my stories were imitations. They weren’t really mine.”

That literary awakening is also a political stance. In a world that flattens or erases African interiority, Moeng insists on texture and nuance. Her Botswana isn’t filtered through trauma or metaphor. Instead, it’s embodied in ritual, emotion, contradiction.

“I wanted to write stories that allowed my characters to be ordinary,” she told me.

And yet, in Moeng’s hands, the ordinary becomes luminous, not through drama, but through the steady attention she gives to the inner textures of daily life, the emotional undercurrents we often overlook.

Living in the ‘in-between’

Her characters often live in the in-between — between city and village, memory and modernity, the longing to belong and the need to leave. Moeng doesn’t dramatise these divides. Instead, she lets them unfold gently, stitched into the texture of everyday life.

“There’s this idea that once you go abroad, you’ve somehow ascended,” Moeng said. “But then you come home, and the same expectations are waiting for you. Maybe even more.”

That double consciousness, the weight from both inside and out, flows through many of the stories. It’s a quiet kind of dissonance, where movement doesn’t always mean freedom, and return doesn’t always mean home. Moeng’s gift lies in making that ache feel both deeply personal and widely familiar — as if the reader, too, is straddling something unnamed and unresolved.

In Small Wonders, Moeng sketches the disorientation of a widow wrapped in the deep blue of mourning. She quietly resists her in-laws’ pressure to hold a traditional death ceremony, and at work, she notices the air shift — once-chatty male colleagues grow quiet around her. Eventually, they return to their banter, but she remains invisible. She feels it on the street too. Something else also unfolds: the quiet emergence of all the selves she’s carried — girl, woman, wife, widow — each rising as life requires.

In Botalaote, we follow a teenage girl who gives up her room for a dying aunt she once loved but now barely recognises and partially resents. She’s 15, full of the restless energy of youth, and desperate to be where the laughter is — at the wedding, with her friends, dressed up and glowing. But instead, she’s told to stay home and care for her aunt. No one asks. No one checks. It’s simply understood: the girl becomes the caretaker. She bristles at the burden. Years later, she realises what she had witnessed: how quickly the boundary between youth and decline can blur, and that carries its own wound, one that only makes sense in retrospect

Silence as strategy

Moeng’s stories refuse simplification — they unfold on their own terms, without spectacle or the need for explanation. They are full of what isn’t said.

“The interior lives of ordinary women are worthy of literary attention,” she told me. “The collection is as much about what isn’t said as what is.” Silence here isn’t absence. It’s strategy, memory, defiance. “I didn’t realise how much of my silence was inherited,” she added. Call and Response carries generational echoes, with all that is handed down, withheld, and sometimes undone.

The stories in the collection made me pause. They slowed me down. And days later, I was still carrying them with me — not as a collection, but as a conversation that hasn’t quite finished. Maybe that’s the magic of it: Call and Response doesn’t end. It waits for you to answer back. And here’s the thing that I didn’t expect.

I didn’t expect stories that were quiet, grounded, and unflashy to rearrange something inside me. But they did. They got under my skin in the best kind of way. There’s no neat resolution, no grand flourishes. Just the kind of storytelling that stays with you while you’re doing dishes, or walking the dog, or staring out the window wondering why your chest feels a little fuller. That’s why you should read it. Not because it performs. But because it stays. DM

Joy Watson is a Daily Maverick contributor; she has worked as a researcher and policy advisor to national states as well as in the global policy arena. Currently, she works for the Institute for Security Studies and the Sexual Violence Research Initiative. Her debut novel, The Other Me, was a finalist for the UJ Prize in 2023.