South Africa may have moved beyond apartheid, but not beyond racial polarisation. Virtually every problem we face in this country is touched by our legacy of systemic racism and the psychological trauma it has caused to people of all races. Read an excerpt from The Human Bridge – Racial Healing in South Africa.

***

South Africa has had five constitutions throughout its history. Each marked a new dispensation, three of which intended and successfully institutionalised white supremacy – the legacies of which are with us today. The decisive break from legalised racism came with the introduction of the interim Constitution in 1993, which laid the foundation for the most progressive and celebrated constitution of our time, the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 – The People’s Constitution.

When the People’s Constitution was signed into law on 10 December 1996 in Sharpeville, the people of South Africa committed to healing from the past racial divisions and building a new South Africa based on human dignity, equality, and freedom.

The People’s Constitution is the best tool we have for racial healing.

Racism = Prejudice × Discrimination

A foundational aspect of racial healing is understanding what the people of South Africa need healing from. Is it prejudice? Prejudice is what we understand as negative attitudes, feelings, beliefs, and thoughts that someone holds about a specific group of people. Such people are prejudicial based on prejudgement and not an actual experience, reason, or justification. While prejudice is not specific to racial grouping, racism has and continues to be a type of prejudice experienced in every corner of the globe to justify the superiority of one race over another or many others.

However, racism is more than just prejudice, which is intolerant, hurtful, and ignorant. Racism is also discrimination, which is determinative, systemic, violent and humiliating. In short, discrimination is unequal treatment based on being a member of a specific group. Since discrimination is behavioural, it is always accompanied by power. The power to dispense preferential treatment, to oppress, and to deny the human rights of those deemed less than human.

In South Africa, racial discrimination has been a source of chronic indignity, both in past and living memory – a massive feat to heal from.

Let me explain.

The institution of racism: some lives matter more than others!

The South African constitutions of 1909, 1961 and 1983 all institutionalised racial hierarchy, inequity, and injustice. For more than 80 years, these three constitutions solidified white power and domination, manipulating systems and institutions to discriminate against Black people in all aspects of their lives. I have intentionally capitalised the ‘B’ in Black. I am of the school of thought, like that of the Black Consciousness Movement, that Black is a unifying identity for people of colour who live in a country where racial disparity remains.

The union for whites only

The Constitution of 1909, which also brought about the Union of South Africa in 1910, initiated what can be characterised as the “Original Sin” with the introduction of the Black Land Act of 1913. As the first major piece of segregation legislation, the act saw the government take control of Black occupied land, restricting Black people from owning or occupying land and opening the door for white ownership of 87% of the land, leaving a mere 7% to Black South Africans, which increased to 13% 20 years later.

While the impacts of land dispossession are well documented, take a moment and imagine what dispossession does to a people.

Solomon Plaatje aptly captures the impact: “Awakening on Friday morning, June 20, 1913, the South African native found himself, not actually a slave, but a pariah in the land of his birth.” (Plaatje, 1995:13)

Senior Advocate Tembeka Ngcukaitobi expands: “The wealth of Africans at the time was measured in cattle, and the reduction of hectares you could keep reduced the number of cattle you could graze … They had to be pushed off their land and deprived of cattle to make them dependent on the new economy imposed on them – the wage economy.” (The New Yorker, 2019.)

The Republic of Psychological Damage

Following the Sharpeville Massacre of 1960, the Constitution of 1961 came into effect, establishing South Africa as a republic, as well as consolidating white supremacy under the banner of apartheid. The 1961 Constitution ushered in a slew of detention-related laws geared to break not only the spirit of the growing grassroots anti-apartheid movements but also the resilience of the body and mind.

The 90-day law, as it popularly became known, empowered the police to detain political activists for 90 days without access to legal counsel or visitors. Jabu Ngwenya, who was detained at John Vorster Square in 1981, describes the experience: “I was upstairs in a cell where there was thick glass, bulletproof type of glass where you couldn’t do anything… there was glass on top of the bars all over. So that cell was very isolated. You felt at times as if you’re mad. You will think until no more… And then the smell, you become part of the smell…” (South African History Archive).

Detainees and prisoners would also serve long periods in solitary confinement in places such as the Johannesburg Jail, which is now a heritage site called Constitution Hill.

Apartheid-lite is still separate development

Unlike its predecessors, the 1983 Constitution established the Tricameral Parliament, which allowed for the House of Assembly for white people, the House of Representatives for coloured people, and the House of Delegates for Indian people.

There was no provision for the indigenous Black people of South Africa, except with the introduction of the Constitutional Laws Amendments Act of 1988, which limited the indigenous Black vote to the Cabinet in the homelands and township councils. In other words, the indigenous Black vote was tokenistic — a vote without power.

While the 1983 Constitution is considered to reflect a change in thinking for the governing party, the National Party, the new constitutional order maintained the exclusion of the majority of the population. It confirmed the ethos of racial prejudice and discrimination: some lives matter more than others.

Racial healing and justice: two sides of a coin

Ironically, it was the same racially segregated Tricameral Parliament that brought an end to legalised apartheid and constitutionalism driven by white supremacy by adopting the Interim Constitution of 1993 – South Africa’s first democratic Constitution. A critical feature of the Interim Constitution was the 34 Constitutional Principles, which laid new foundations for all the people of South Africa to be regarded as equally important.

The interim Constitution laid the foundations for the most progressive and celebrated constitution in history, the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 – the People’s Constitution. For the first time, all South Africans became the architects of a plan for their country and future generations. The People’s Constitution is infused with the hopes and dreams of the country South Africa ought to be, and bestows fundamental human rights not based on race, but on the intrinsic value of being human.

When the people of South Africa wrote the People’s Constitution between 1994 and 1996, they made a deliberate choice to build a united and democratic South Africa through healing from a cruel and racist past. The founding values make it crystal clear that:

The Republic of South Africa is… founded on… human dignity, the achievement of equality and the advancements of human rights and freedoms. (Section 1(a) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996)

However, after 30 years in a democratic South Africa, the legacy of nearly 90 years of racial discrimination — not to mention the socioeconomic injustice in the fabric of our society. We remain the most unequal country in the world. Poverty remains Black, cyclical, and generational. In juxtaposition, privilege remains with a white face and is equally cyclical and generational. How do you heal when the causes of your wounds and trauma are part of your daily lived reality?

We radically put the People’s Constitution to work. To do that, the people of South Africa must know, own and protect the Constitution to realise its promise.

The People’s Constitution challenges us to confront our prejudices through deep introspection and engage with the cognitive dissonance of a society terrorised by white supremacy for centuries. The People’s Constitution also challenges us to tackle racial healing from institutionalised discrimination and the intended consequences thereof. Woven in every provision, it makes clear that justice must be demonstrated for racial healing to take place. We see that in the opening page of the People’s Constitution – The Preamble:

We, the people of South Africa; Recognise the injustices of our past;

… We … adopt this Constitution as the supreme law of the Republic so as to –

Heal the divisions of the past and establish a society based on democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights;

… Improve the quality of life of all citizens and free the potential of each person …

Let us live the People’s Constitution by tackling these challenges head on. Let us demonstrate justice, and healing for all humanity. DM

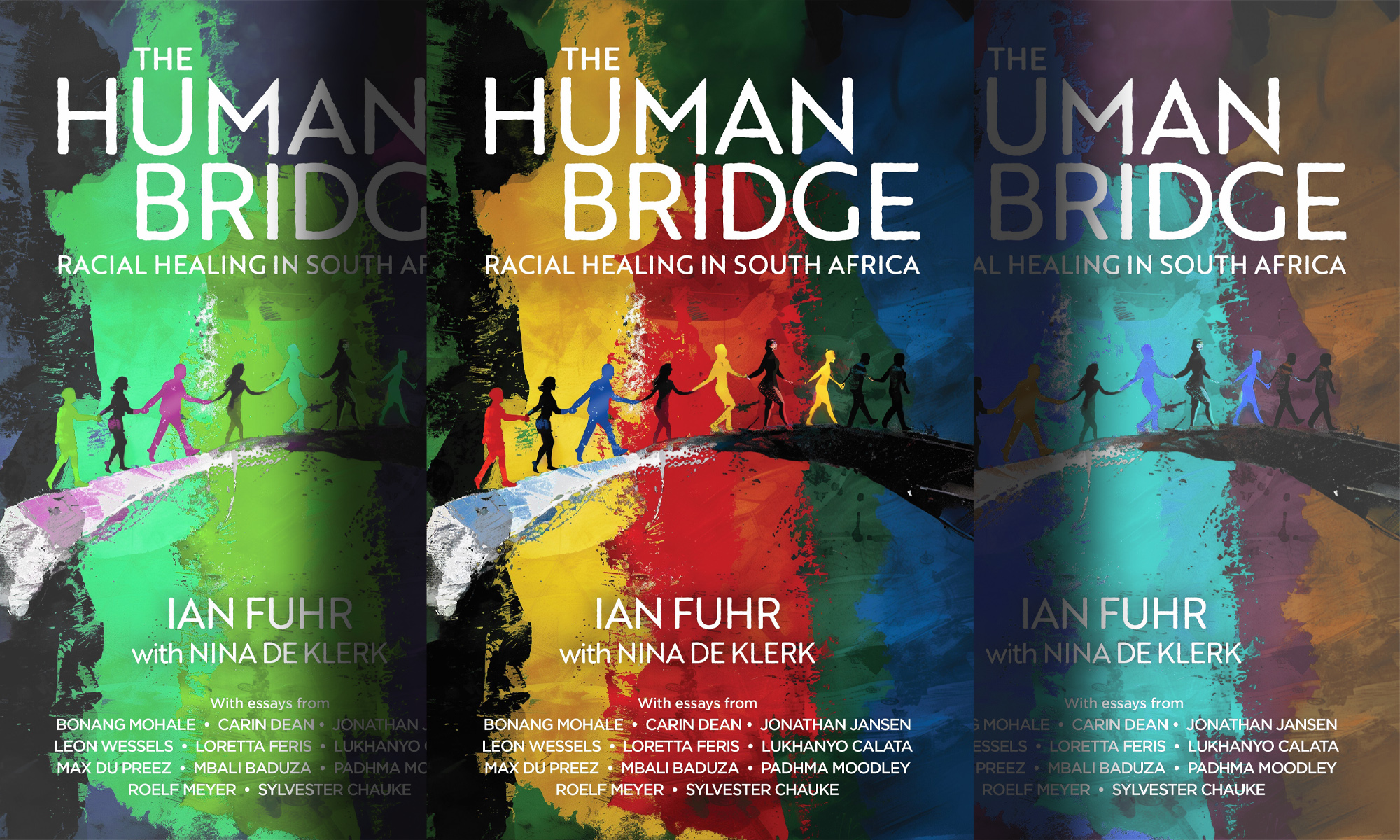

The Human Bridge: Racial Healing in South Africa by Ian Fuhr with Nina de Klerk is published by Tracey McDonald Publishers, and available online and in all good bookstores. Recommended retail price: R350.00