I first met Rashid Vally in 1975, during exploratory research for a film on black township music that was never made due to the Soweto Uprising of 1976, but which marked the beginning of my life as a South African. He was most helpful to the young know-nothing that I was and in later years to the ageing know-nothing I became.

Rashid Vally: During the 1950s my father had a restaurant near here called Azad. There used to be a Wurlitzer jukebox in there and the black customers used to play all that big band American jazz, Glenn Miller, Louis Jordan, and so on. And I used to get a few coins for playing the thing for them. Then my Dad decided to open a store, and he sold music, Indian from the films, for the Diwali festivals, and Muslim religious music. So he came with an LP from one of the plants, and we had a turntable, and he would buy new ones. I started to enjoy the big band stuff, and the black customers would come and say where did you get that lovely stuff and ask if we sold records, so I thought maybe I am sitting on something here.

At the end of the 1950s we introduced 33rpm LPs of jazz at the old Koh-i-Noor at 11 Kort Street, and then the musicians who used to come in to listen said, ‘Hey, why don’t you record us?’ So we started recording music of the coloured langarm dance bands from Fordsburg, Fietas, Vrededorp, for their events. The Merry Mascots and so on. My late father used to hire studios at Troubadour, and I went with him and saw how it was done. I’ve never owned a studio, always hired them. As non-whites we could not have shops in those areas, only down here. When I bought this shop I couldn’t even own it in my own name because of Group Areas and so I got Peter Gallo to “nominate”; that is, front it for me. Then later they let us actually buy here, as it was close enough to Oriental Plaza. We were recording dance music, and Gallo Records were distributing. I used to sell the American records on a bicycle, to the various stores, but to black workers, not whites, who weren’t interested.

I used to go and listen at Dorkay House, the only venue for black musicians to play at that time. And Dollar Brand used to stay at the Planet Hotel in Fordsburg, the only place he could stay. Dollar, he was already Abdullah Ibrahim, walked into the shop one day, and he said I hear you are doing good work, and why don’t you record me? I said could you do the Tintinyana you did with Elvin Jones? He said sure. And the first album was Peace with Nelson Magwaza and Victor Ntoni on bass, in 1971, and then more dance bands. Then we did one with Kippie Moeketsi called Dollar Brand + 3, only released two years later. You couldn’t tell Dollar what to play; sales were not his priority then.

Mannenberg was done in 1974. Dollar called and said he needed money, I’ll play whatever you want for R10,000. So I borrowed the money from my Dad, and we went to Cape Town, and we were in the studio for six days. First I recorded Underground in Africa, with the group name Osviti, and it was Basil Coetzee and Robbie Jansen on tenors, Rashid Kabdee on drums, someone on bass, in 1973. We used the same group for Mannenberg. We did a whole lot of songs, but I was looking for the hit in the mix. Abdullah could sense that, and on the second day, saxophonist Morris Goldberg walked in, and wanted to play. So he was on. Dollar left the grand piano and went over to this old upright, and he found that it had these thumbtacks on the hammers, a piano used for making ad jingles, and Dollar loved the sound. Soon the first strains of Mannenberg began coming out, and he said hey, Basil, Robbie, come here, and then it was cooking. And Morris came on, and they rehearsed for 35 minutes. Then they just recorded it, with the three horns, and Dollar came with the name, after a photograph he took of a Mrs Williams in Manenberg. But when it came out, we didn’t put Morris’s name on it. I admit we were a bit racist against him, and later he asked me about it, and I took the blame and apologised. Such were the times. I took it to Teal Records to make the master, and I used to play it at my shop as a sample and everyone went mad, so I knew this was our hit. We used to play it loud in the street at Kort. I went to Teal Records, and asked them to press the thing, 5,000 copies, and when it came out, jazz but a mix of old and new, it sold the 5,000 copies in a month. Doing my own distribution was tough; finally I went back to Gallo for remastering and distribution, as now they saw the commercial value of it. My brother-in-law designed the sleeve at home. We did all of Abdullah’s covers ourselves.

After Mannenberg we did six or seven albums. They are ageing like wine, but were ahead of their time then. Somehow it got to the United States, and it was released by AudioFidelity as Cape Town Fringe. Once it was heard on radio, black Americans used to write, asking for the song. But it was all politics, and I never saw some money from it. Meantime I booked the studio at Gallo, and we recorded Blues for a Hip King and some others, all on As-Shams label. Dollar also played soprano sax. Then in 1975-6 we recorded Pat Matshikiza on piano, with Kippie on alto and Sandile Shange on guitar, who told me they had an “answer” for Mannenberg. This became the legendary LP Shona. Kippie wanted to do another, and we called it Shikiza Matshikiza. We did one with young Pops Mohamed, who was a self-taught dance band player for the langarm, an album called Black Disco. We worked again with Basil Coetzee, on flute, and then with guitarist Sipho Gumede, and with Dollar again in 1976, on African Herbs, with Dennis Mphale on trumpet, Barney Rachabane on tenor, George Tyamzashe on trombone, Sipho, Kippie. In the studio, Dollar liked to scare all of them silently. Still does. And we did Hal Singer’s Blue Stomping here on tenor and Kippie on sax. Yoooo! People tell me Sun Records is historical, I should reissue (note: in 2023 Zozotown did so on vinyl with As-Shams Archive Vol. 1), but little has changed in this country as far as distribution for independent producers is concerned…

Even so, Koh-i-Noor and, more importantly, Rashid Vally kept going over the years. His legacy as the first, and certainly among the visionary best, of South African black music producers is well assured. DM

* Interview with Rashid Vally, 23 July, 2005.

David B. Coplan, Professor of Anthropology, Emeritus, Wits University and musician. Author of In Township Tonight, among many other works.

Op-eds

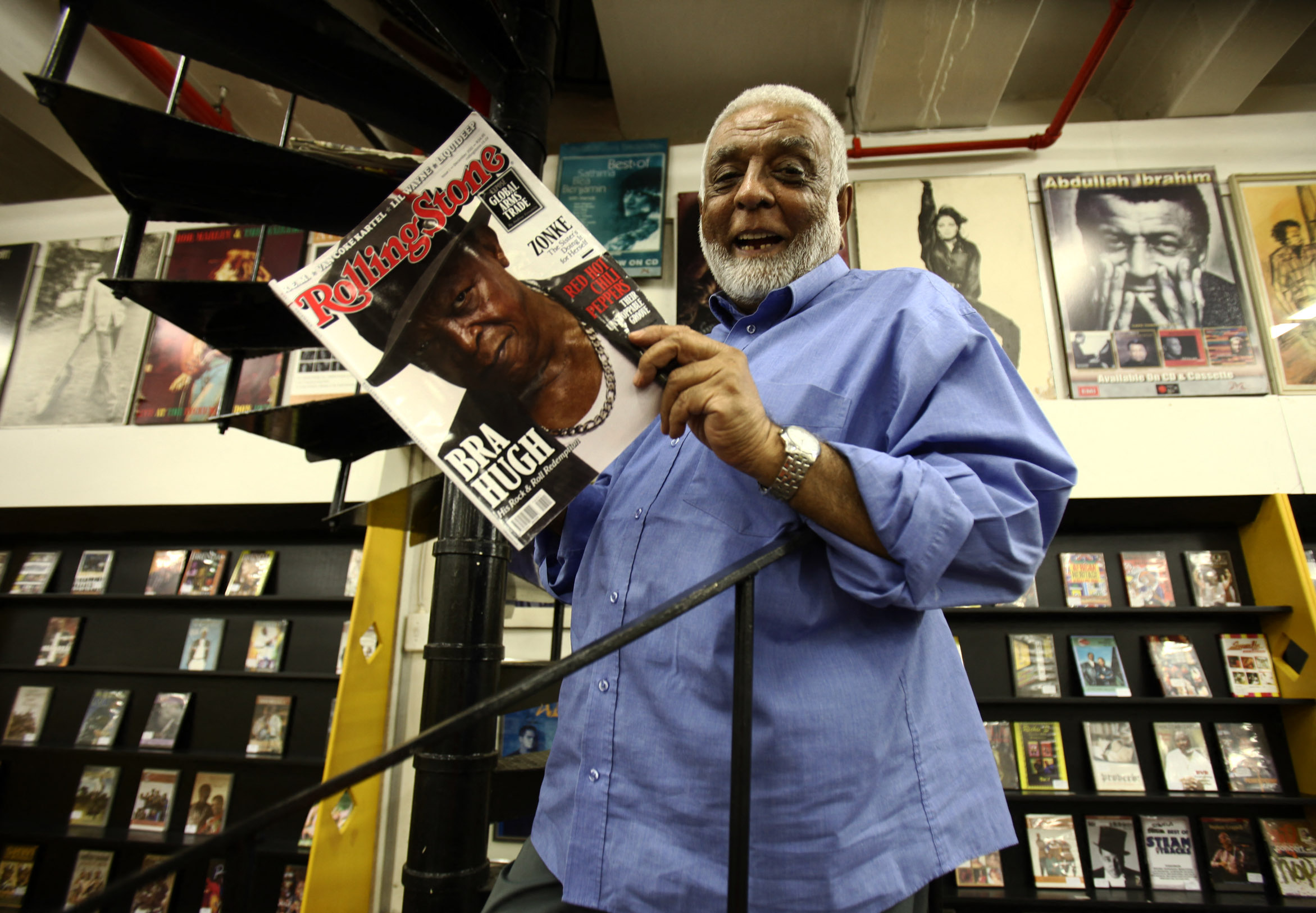

Independent black music production and marketing pioneer Rashid Vally takes his final bow

This week we received the sad announcement of the passing of pioneer independent record producer Rashid Vally, owner of the foundational jazz record label As-Shams and the record store Koh-i-Noor in Fordsburg. He was 85. Tributes from the Johannesburg jazz community have appeared in the media by now, but as I had the pleasure and benefit of knowing Rashid I thought I would share part of a conversation I recorded with him at Koh-i-Noor in July 2005.*