When remembering episodes of violence, whether this is the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, June 16 1976, or Marikana in 2012, we should recognise that there are many others whose deaths are worthy of commemoration.

And remembering these victims of violence should also be a way of committing ourselves to creating a society in which violence is no longer so deeply embedded in the relationships between us.

It is now 11 years since the Marikana massacre, the fatal shooting by police of 34 men on 16 August 2012. Almost all of those killed, and the unknown number who were injured, were mineworkers who were on strike at the Lonmin Marikana mine in North West.

Read more in Daily Maverick: 'Witnessing the shooting of people at Marikana left a massive scar'

In recognition of the scale of this tragedy, and as part of a commitment to redress for the families of the deceased and other victims, there are some who continue to commemorate the Marikana anniversary. Last year a few continued to call for the anniversary to be declared a public holiday. This year, as part of the build-up to the party’s 10th anniversary celebrations, the Economic Freedom Fighters convened a gathering at Marikana.

Last year’s commemoration of the 10th anniversary of the massacre attracted a relatively high level of interest, including coverage in international media. But as August 2012 recedes further into the past there is a sense that the motivation for commemorating Marikana each year is weakening.

As we mark yet another Marikana anniversary it may be worthwhile to explore the question: faced with a surfeit of violence, and a multitude of other intractable social problems, what should we aim to achieve by memorialising Marikana?

Mine workers chating songs abd carrying weapons while gathering outiside Nkaneng informal settlement near the Lonmin mine in Rustenburg north west demanding a wage increase from their employers. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla (Foto24/Gauteng))

Mine workers chating songs abd carrying weapons while gathering outiside Nkaneng informal settlement near the Lonmin mine in Rustenburg north west demanding a wage increase from their employers. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla (Foto24/Gauteng))

Scale of the violence

Each death from violence is attended by deep personal trauma and multiple dimensions of loss suffered by family and others. As an incident of large-scale violence, Marikana was one of the most horrific episodes of violence to have occurred in post-apartheid South Africa.

The number of deaths, and the graphic television and photographic coverage of the incident have served to amplify our awareness of the trauma and loss associated with the death of each one of those killed.

If it is the scale of violence that matters, however, then Marikana’s claim to memorialisation might be seen to have been superseded by the events of July 2021, during which an estimated 354 people died in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. Most of these deaths occurred during three days of mass looting that were triggered by attacks on warehouses, malls and other infrastructure allegedly carried out by loyalists of former president Jacob Zuma.

Read more in Daily Maverick: One year ago, South Africa’s darkest eight days in 19 photos

However no one, other than perhaps the immediate families and friends of those killed, seems to want to memorialise most of those who died in the July 2021 unrest. This is partly related to the fact that many of those who died are assumed to have been implicated in one way or another in the looting or other violence.

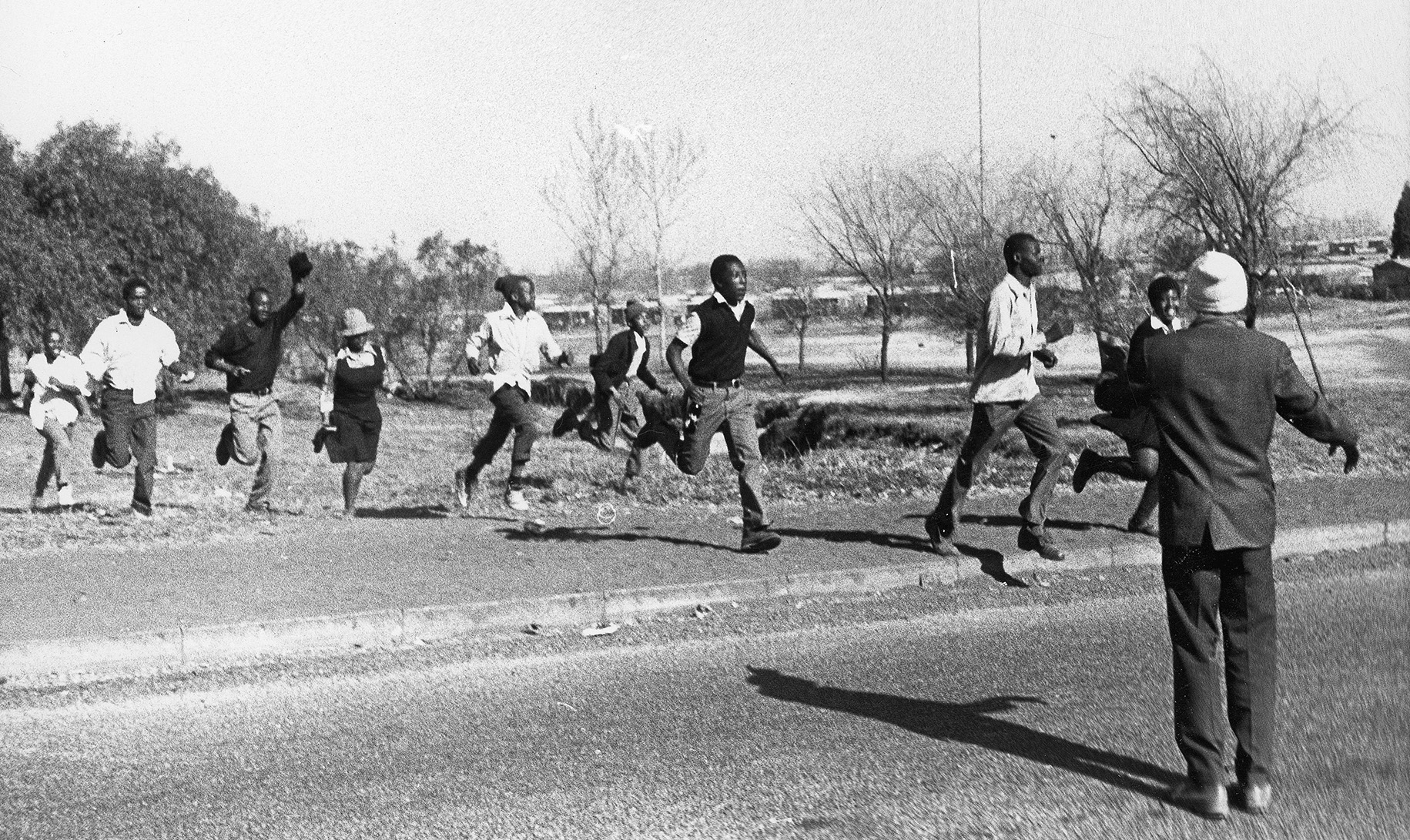

An image taken during the Sharpeville Massacre. (Photo: Supplied)

An image taken during the Sharpeville Massacre. (Photo: Supplied)

In so far as there is any tendency to memorialise the events of July 2021, it has focussed on the troubling story of the “Phoenix massacre” in which roughly 36[1] people were killed, many of them at the hands of Indian vigilantes caught up in a frenzy of violence motivated by racial prejudices and fears that were directed randomly at black African members of the public. Some of the victims were suspected of being connected to the looting that proliferated at the time.

Social and political purpose

Of course, we already memorialise two major episodes of violence from South Africa’s apartheid past. Two public holidays, Human Rights Day on March 21 and Youth Day on June 16th commemorate events that culminated in a fusillade of police bullets against the bodies of black South Africans protesting against apartheid.

Students protesting during the June 1976 uprising in South Africa. The Soweto uprising was a series of demonstrations and protests led by black school children in South Africa under apartheid that began on the morning of 16 June, 1976. (Photo: Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

Students protesting during the June 1976 uprising in South Africa. The Soweto uprising was a series of demonstrations and protests led by black school children in South Africa under apartheid that began on the morning of 16 June, 1976. (Photo: Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

As public holidays, Human Rights Day and Youth Day have an explicitly social and political purpose. In the words of the preamble to the Constitution, they are supposed to be part of what we as a country do to “honour those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land”. As such they are intended to contribute to building social cohesion among South Africans and loyalty and commitment to our democratic state.

They are therefore intended to symbolise a commitment to a new social order in which not only are members of the public protected from arbitrary death at the hands of the state, but also in which we enjoy “social justice and fundamental human rights” and a decent “quality of life”.

Protesters being detained during the June 1976 uprising in South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

Protesters being detained during the June 1976 uprising in South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

A watershed moment

As with those who died in Sharpeville and Soweto, the 34 deaths at Marikana were deaths at the hands of the state. At the time that it occurred, the Marikana massacre was seen by some as a watershed moment which embodied the failure of the post-apartheid state and the “liberation movement” led by the African National Congress to achieve the “better life for all” that had been promised in the elections of 1994.

Marikana seemed to crystalise this failure. Notwithstanding non-racial democracy and the police service that represented it, it was once again the brutalised bodies of 34 black miners that lay scattered in the dust at the two sites where the massacre took place. The massacre, therefore, seemed to reflect the degree to which the post-apartheid political order continued to embody the structural relationships of power of the apartheid era.

Cycles of violence

But there is another dimension to the Marikana tragedy. During the five days prior to the massacre, 10 people were killed at Marikana. Of these, three were also killed by police. The other seven, including two police and two security guards were killed, or are suspected to have been killed, by strikers.

The massively disproportionate violence unleashed by the police armed with R5 automatic rifles on 16 August was ultimately what came to define the episode. But what emerges from engagement with the full Marikana story is not merely a one-sided account of continuing state repression and brutality, or the “toxic collusion” between the state and big business, but a more complex story about violence.

Members of the South African Police Service Forensic Unit Police investigate the scene where striking miners were killed by police in Marikana near Rustenburg, South Africa on 17 August, 2012. (Photo: EPA / STR)

Members of the South African Police Service Forensic Unit Police investigate the scene where striking miners were killed by police in Marikana near Rustenburg, South Africa on 17 August, 2012. (Photo: EPA / STR)

Repeatedly over the early days of the strike, violence by one party led to an escalation in fear, and the “arming up” of the other side, whether this was the spears and pangas of the strikers, or the R5 rifles brought in by the tactical units deployed to bolster police ranks after the fatal clash between strikers and police on 13 August, three days before the massacre.

Looked at in this way, Marikana is not only a story about the persistence of apartheid-era social relationships, but also a story of how violence continues to be embedded in South African society. It is therefore also a story of mutually reinforcing cycles of violence, in which actions by all parties were shaped by fear of their adversaries.

Along with the issue of accountability of the state and business owners, it also raises unanswered questions about the complicity of some of the strikers in violence.

Mgcineni "Mambush" Noki 9in green), one of the leaders of mine workers, at the "Koppie" near Nkaneng informal settlement outside the Lonmin mine in North West. (Photo :Felix Dlangamandla (Foto24/Gauteng))

Mgcineni "Mambush" Noki 9in green), one of the leaders of mine workers, at the "Koppie" near Nkaneng informal settlement outside the Lonmin mine in North West. (Photo :Felix Dlangamandla (Foto24/Gauteng))

Reasons for memorialisation

Current statistics on murder indicate that on average 520 South Africans die in acts of violence every week. Rather than being regarded as worthy of honour or memorialisation, the vast majority of these victims disappear into the continuing flood of innumerable, faceless victims of violence.

This is not to say that there are not some victims who are more worthy of memorialisation than others. But surely it is not only those who have died at the hands of the state, but many others, whose deaths should be more fully memorialised?

Self-sacrifice in a cause that is noble would be one of the criteria that motivates that some deaths are particularly worthy of commemoration. But the pantheon of those whose deaths should be remembered for this reason should now justifiably also include not only those who died for their opposition to apartheid, but also the growing number of whistleblowers and other opponents of corruption who have been murdered.

Potentially it also includes others, like police officers who have died in the line of duty who are rightly formally commemorated by the SAPS each year, or civilians who have given their lives for others in other circumstances. Among the deluge of violent deaths each day and each week, few if any of these are remembered.

A group of miners fleeing scene one, while police are firing live ammunition and teargas. Some can be seen alredy lying on the ground outside nkaneng informal settlement near the Lonmin mine in Rustenburg north west on 16 August, 2012. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla)

A group of miners fleeing scene one, while police are firing live ammunition and teargas. Some can be seen alredy lying on the ground outside nkaneng informal settlement near the Lonmin mine in Rustenburg north west on 16 August, 2012. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla)

Foregrounding violence

Of course, South Africa has other sources of suffering. There is poverty, unemployment, hunger, mental and physical sickness, and corruption. But, even relative to the scale of misery and harm caused by these problems, violence in South Africa is certainly not a lesser concern.

Linked to the scale of violent trauma that this country has faced and continues to face, many of us are in some respects inured to violence and tend to treat most reports of violence with little more than indifference.

Absent ourselves or those close to us being directly victimised, it is only when something about the victim elicits particular sympathy from us, or there is more large-scale violence with a high death toll, that we are able to muster more than a sense of indifferent resignation.

While remembering the victims at Marikana, Soweto or Sharpeville, we should also remember the countless victims of violence who we have not memorialised.

We should remember that there are many other deaths that are worthy of being remembered and people whose memory should be honoured.

And the memory of these incidents should also consciously and purposefully be used towards creating a society in which violence is no longer so deeply embedded in the relationships between us. DM

David Bruce is an independent researcher and consultant to the Institute for Security Studies.

Police open fire on a group of fleeing mine workers. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla (FOTO24/GAUTENG))

Police open fire on a group of fleeing mine workers. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla (FOTO24/GAUTENG))