According to The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), foreign direct investment flows into South Africa in 2020 almost halved to $2.5 billion from $4.6 billion in 2019, which was a 15% decline from around $5.4 billion in 2018.

The cumulative total over the three years amounts to $12.5 billion, which can seem like a really big number in rand terms. But President Cyril Ramaphosa in 2018 set an investment target of $100 billion over five years, and at an investment conference in Sandton in October of that year, no less than $55 billion in investment pledges were made by various titans of industry.

Over half way there! Talk about action, talk about promises kept! From the Karoo to the Limpopo, it was like money was falling from the sky. Investors were besot by South Africa, coming on bended knee, carrying suitcases bulging with cash.

Talk about smoke and mirrors.

UNCTAD monitors this kind of stuff and while its data may not be pinpoint in its accuracy, it releases its global FDI finds annually, and they are a pretty good indicator of wider trends, And by almost any measure, South Africa is a laggard.

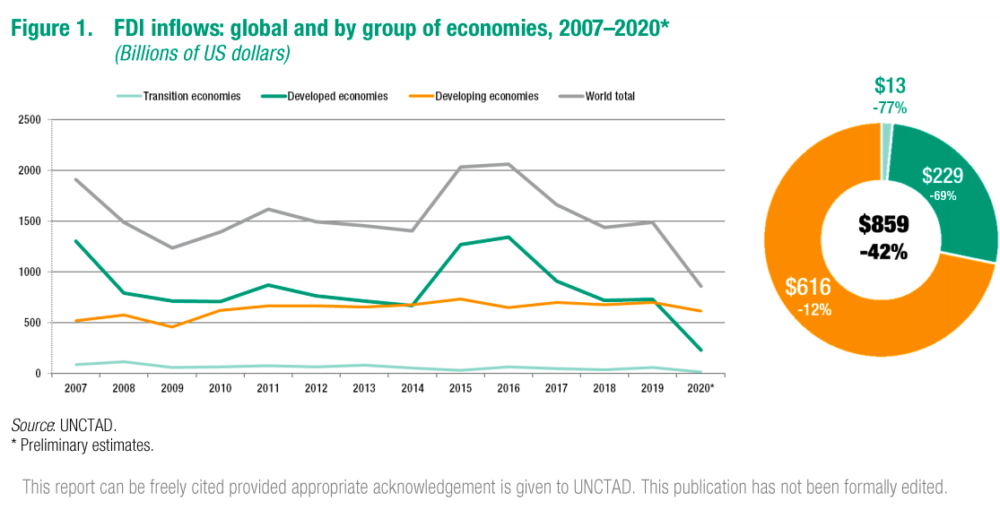

So in 2020, almost everywhere, FDI flows faltered because of the pandemic and the lockdowns to curtail its spread. Globally, the amount of FDI in 2020 fell 42% to $859 billion from $1.5 trillion in 2019. At 69%, the decline was sharpest in developed economies such as Europe and the US.

By contrast in developing economies - South Africa's broad peer group - the decline was far less steep at 12%. Sub-Saharan Africa recorded an 11% fall in FDI in 2020, which all things considered - the crash in oil markets, the global economic contraction, the rise in investor risk aversion - was not a train smash. Then you look at South Africa's 46% plunge, and the image that comes immediately to mind is an economy going off the rails.

UNCTAD also notes that: "The share of developing economies in global FDI (in 2020) reached 72% - the highest share on record." A lot of that has to do with China, which of course completely bucked the trend by notching a modest 4% rise in FDI inflows last year. The wider point here is that the FDI flows that are out there are being channeled into developing economies, and yet South Africa can still only attract a trickle, while a tsunami passes by.

Pretoria is clearly missing the boat.

So what's going on here? On the investment flows, much of the $55 billion pledged in Sandton in the heady days of late 2018 was already in the country or in the pipeline, to be spent over an extended period of time. South Africa also has domestic sources of investment capital, but a low savings rate means it is never enough, which is why foreign capital is so essential.

There are also foreign portfolio flows into the JSE and bond markets, but unlike FDI, this is capital that can slosh in and out with relative ease. FDI is coveted - the platinum standard, as it were - because it is capital that gets spent on physical assets such as the building of factories or mines or labs or shops, anchoring itself into the economy.

This also translates into employment, which is why every FDI announcement typically trumpets the number of jobs it creates, or aims on paper to create.

And South Africa is just really bad at attracting FDI - the facts speak for themselves and the reasons are as clear as a bottle of cane. Eskom is at the top of the list. Factories and mines - you know, the things one expects to find in a modern, industrial economy - require reliable power supplies. Yet from the DMRE to NERSA, new renewable and self-generation projects remain stillborn, crushed under mountains of red tape.

The impression is that such projects will only get the go-ahead when ANC cadres can benefit - that may be unfair, but recent history suggests this is a plausible explanation for the inertia. Also on the mining front, the dysfunctional DMRE cannot even produce a functioning Cadastre, a publicly-available overview of geological data and the mining rights it has awarded. Small wonder South Africa accounts for less than 1% global mining expenditure on exploration. And without exploration, there won't be any new mines built.

This list could go on, of course. Planned investments into new brewing capacity have been killed by the ham-fisted policy of prohibition. South Africa's high rates of violent crime and social unrest dramatically add to security costs and hence the cost of doing business. Tax rates are very high with a very low rate of return.

The state suffers from poor capacity: a foreign investor's first impression of South Africa may well be formed by dealings with Home Affairs, which is by most accounts is a shambolic mess. Crucial infrastructure is falling into a state of disrepair, which is what happens when cities just as Johannesburg are run by cadres with eye on their own bottom line.

Policy goal posts keep changing, and surging government debt levels will continue to sap the value of the rand currency, adding to the layers of uncertainty. It also raises borrowing costs for the private sector as it must go to lenders against the backdrop of a sovereign credit rating on the scrapheap of junk. Productivity levels are generally low and confidence levels are in the gutter.

Attracting FDI does not mean a country has to bend over and kiss the ring of capital in some Trumpian fantasy by shredding all of its regulations and labour laws. In an age of ESGs (environmental, social and governance concerns) and increasing corporate disclosure, few companies want to be associated with things like child labour or a mining project that poisons hundreds of elephants.

But they want a return on their capital and a stable investment environment. South Africa at the moment is not offering either. "$12.5 billion in three years!" This is hardly an inspiring slogan for political rallies. But the fact of the matter is it's a fact. DM/BM

Business Maverick

Smoke and mirrors: UN data shows Ramaphosa's investment drive is barely alive