On a chilly May morning at Bushmans Kloof, the Queenstown-based artist Stephen Townley Bassett was suddenly nudged by his wife, Karen. From the foot of their bed, a pair of dark, curious eyes was staring at the humans, flabbergasted.

The shock was mutual.

Bassett sprang up, shooed the baboon out of the room and shut the window. He knew better than to have left it open. Bassett knows this part of the Cederberg well, knows that its roaming baboons can be brazen. Back in the early 1990s he spent 18 months here working as a field researcher, roaming the mountains on foot, documenting San rock art.

It was a defining period in his adult life, a time of hands-on learning. When he began that assignment for Stellenbosch University’s archaeology department, there were fewer than 20 known rock art sites in the area; by the time he finished there were more than 90.

Three decades later, Bassett was back in his old stomping ground to present a workshop at Bushmans Kloof, now a luxurious retreat centred on some of the original farm buildings from a time before this place was returned to wilderness and stocked with game. To reach it, you drive through Clanwilliam and head east on Pakhuis Pass for 34km, turning into the 7,500ha fenced conservation area with its dirt roads and endless views of empty magnificence.

The terrain at Bushmans Kloof in the northern Cederberg. (Photo: Keith Bain)

The terrain at Bushmans Kloof in the northern Cederberg. (Photo: Keith Bain)

It’s as serene and majestic a place as you could hope to find, like travelling back in time, your eyes lost in an enfolding expanse of craggy rocks and purple mountains looming above valleys of scraggly fynbos.

This entire swath of northern Cederberg is a distinctive landscape of iron-oxide-pigmented sandstone that glints in the sun like the surface of some alien world. Inundated with finger-like rock towers and burnt-orange overhangs that look as though they’ve been sculpted by some fantastic hand, it’s a place that might put you in mind of Moab in Utah, Morocco’s Todra Gorge, or Castle Hill in New Zealand.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Magic season in Cederberg’s high valleys

The beauteous rockland is also inundated with natural shelters, places where the first human inhabitants of the area found protection from the elements and made fires around which to conduct rituals, dance all night, witness shamanic trance rites and paint.

Which is why Bushmans Kloof is also brimming with rock art. There are some 135 known sites where the San painted scenes that to this day continue to baffle and enthral archaeologists. Of these, about 15 are accessible on self-guided hikes or with the expertise of rock art curator Londi Ndzima.

Londi Ndzima at Fallen Rock Shelter, one of the many rock art sites at Bushmans Kloof. (Photo: Keith Bain)

Londi Ndzima at Fallen Rock Shelter, one of the many rock art sites at Bushmans Kloof. (Photo: Keith Bain)

Many years before Ndzima became infatuated with rock paintings, though, Bassett had begun documenting the sites here. His renderings of these artworks hang in the lodge’s bar and lounge and his books featuring millimetre-accurate reproductions of San rock paintings from across the country can be found in the lodge’s heritage centre, a mini-museum dedicated to rock art and the people who created it.

Connecting with the past

Bassett calls himself a forensic artist. He also uses technology accessible via a smartphone in order to include in his reproductions parts of some paintings that have faded completely over time. Called DStretch, the app he uses has applications in various archaeological fields. “It uses algorithms to reconstruct light wavelengths in order to expand the range of the human eye,” Bassett said.

Such technology means that, in his studio, Bassett is able to compile a complete picture of the many successive layers of paintings that have existed across time.

DStretch aside, in all other respects his methods are ultra old school. Having relinquished commercially available paints, he collects ochre-rich rocks, uses charcoal and has experimented widely to create white pigment using crushed bones, ostrich eggshells and the white faeces of raptors.

Stephen Townley Bassett describes shamans going into a trance to bring back images. (Photo: Keith Bain)

Stephen Townley Bassett describes shamans going into a trance to bring back images. (Photo: Keith Bain)

He said he’s tried using the faeces of other predators, but these tend to be full of hair and other undigested material. “Raptor faeces are incredibly strong and they break down into a very, very fine powder.”

His homemade, nature-derived pigments might also include blood, saliva, egg, animal urine and gall.

Bassett’s interest is in the technologies that powered San artists. He operates in the realm of experimental and speculative archaeology, gathering the materials for the tools of his trade by foraging in the wild and occasionally also hunting for animals.

On one expedition, he found a ground squirrel, skinned it, and harvested hair from it. “You get different quality hair from different parts of the animals, so from a springbok you might get softer hair from around the ear or the back, but the tail is much coarser, so I make a fatter brush with that. Feathers make good brushes, but are very fragile.”

He’s used giraffe’s kneecaps as mixing bowls and antelope scapulas as paint palettes. Basically, whatever the landscape provides, he figures out ways to use them.

“That’s the way I am,” he said.

“I’m not an academic. I’m a practical, hands-on kind of guy. I like to actually do it, to figure out whether something works or not by doing it myself. A lot of people speculate about these things, but I want to find out for myself just how practical it really is.”

Stephen Townley Bassett and Londi Ndzima lay out some of the equipment Townley has made to emulate the San paintings created thousands of years ago. Townley uses only foraged and hunted materials. (Photo: Keith Bain)

Stephen Townley Bassett and Londi Ndzima lay out some of the equipment Townley has made to emulate the San paintings created thousands of years ago. Townley uses only foraged and hunted materials. (Photo: Keith Bain)

During a painting workshop on Bushmans Kloof’s open-fronted breakfast terrace, Bassett had us crushing stone-derived powders and mixing these with raw eggs to produce paints that we applied to cardboard using brushes he’d fashioned for us from feathers.

It was a compelling activity, trying to imitate the style and substance of the San artists we’d learnt about, and in the process realise just how intricate their brushstrokes were, how tenderly they shaded.

Bassett said that while he’s primarily interested in San painting technology — the implements, pigments and paints — the long hours spent in the company of the artworks have given him cause to speculate about what might have inspired the artists.

Aside from the practical function of creating pigments that would adhere to rock surfaces, he said there’s reason to imagine that some of the methods were more akin to magic, connected with spiritual beliefs.

Stephen Townley Bassett demonstrates fire making the ancient way. (Photo: Keith Bain)

Stephen Townley Bassett demonstrates fire making the ancient way. (Photo: Keith Bain)

He described, for example, how during trance, the shaman would haemorrhage from the nose, take his blood and, along with sweat from under his arm, rub it on people. “That blood was a link with the eland, which haemorrhaged from the nose when it died. They saw a connection between the eland and the shaman in a trance.”

He said that in this way, by rendering an eland on a rock surface, the artist might have felt some sort of kinship with it — or gained power over it. To test these ideas, Bassett has used his own blood in some of his paintings, “the way the shaman would have used his own blood in order to give a painting a certain potency”.

He said that “even as a 21st-century person” he has gained a certain thrill or satisfaction from putting his own blood into the paint mixture. “I thought, man, this painting is potent, that it added another dimension to the image.”

Not that Bassett presumes to have the answers. “I’m merely the scribe, simply deciphering what’s on the rock,” he said. He talked about attempting to “crack the code” to understand something that can perhaps only be discovered by immersing himself in the practice in an attempt to get inside the headspace of the artists he’s in awe of.

“It might be genetic,” Bassett said of his more extreme Indiana Jones tendencies. “Some of my family have done seriously wacky things.”

Hereditary passion

Bassett said he recalls seeing his first San painting at age 14; he’d been spending time with his adventurous, eccentric uncle, “Ginger” Townley Johnson. Ginger’s own interest in rock art had been passed down from his father who, from as early as 1910, had dedicated considerable time to finding rock paintings in the vicinity of Oudtshoorn.

“Ginger documented hundreds of sites across South Africa,” said Bassett. He kept busy in the Cederberg from the 1950s through to the 1990s, creating records of paintings that are now in university and museum databases.

Bassett’s contact with rock art sites during his teenage forays with his uncle stayed with him. In his early 30s, he finally gave in to his genetically wired eccentricity, abandoned a corporate career and embarked on a kind of maverick pursuit of adventure that eventually saw him relocating to the Eastern Cape to be nearer the country’s rock art heartland.

The rocky outcrops of the Cederberg create shelter from the elements. (Photo: Keith Bain)

The rocky outcrops of the Cederberg create shelter from the elements. (Photo: Keith Bain)

There he embarked on an obsessive project of San art documentation.

For Bassett, the artworks are a way of connecting with people across time. “You have to go back and live like a Stone Age person,” he said. “And for an extended period of time start getting into the minds of these people.”

His approach is a practical, hands-on way of connecting with the San artists, attempting to think and feel as they might have done.

“How many times have I stood in front of a rock painting and thought that in this very place maybe 1,500 years ago there was a chap painting for the first time? As I work, I wonder what was going through the artist’s mind. What was he trying to represent?”

Theories of why these paintings exist abound. At Bushmans Kloof, we discussed these theories over breakfast, lunch and dinner, and during high tea served on one of the terraces. We talked about them on drives across the reserve, on walks to the edge of the lake, and in one of the caves where the people we were discussing had painted.

On the morning after the baboon incident, Bassett and Ndzima had us traipsing across the rocky terrain to reach one of the reserve’s better-known art sites, Fallen Rock Shelter. The tucked-away, open-sided cavern seemed an ideal place to seek protection from the elements, build a fire, tell stories and watch as the shaman went into a trance before returning with visions from the spirit world which would then be translated into paintings.

Stephen Townley Bassett and Londi Ndzima at Fallen Rock Shelter. (Photo: Keith Bain)

Stephen Townley Bassett and Londi Ndzima at Fallen Rock Shelter. (Photo: Keith Bain)

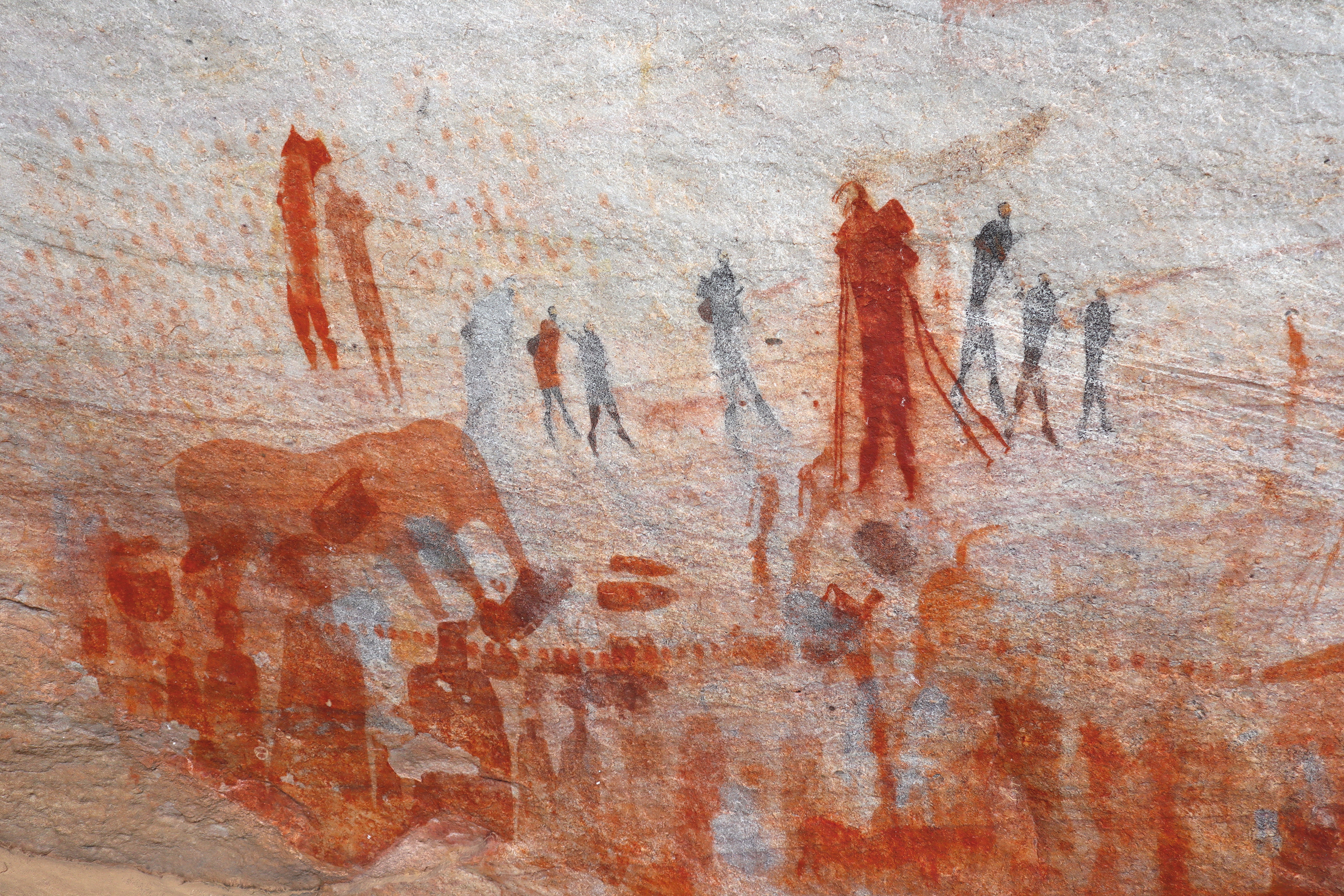

The shelter’s main wall is imbued with a tantalising number of figures, some of them as vivid as if they’d just been painted, others more faded, some very obscure.

Ndzima said the San believed there was another life behind the rock.

“The rock surface was a curtain to a different world. Most paintings were executed by the shaman who would visit the spirit world during a trance induced through dancing ... to the point of dehydration. When the shaman’s spirit returned to his body, he would know precisely which plant to use to heal a sick person.”

Also seen during these altered states, and later painted on the rock wall, were so-called “entoptic visions”, visuals from a place beyond the tangible world.

“They were things seen in the corner of your eye,” said Ndzima. In paintings, they’re sometimes depicted as zigzags or other difficult-to-explain phenomena, maybe strange lines emanating out of human heads or what appear to be rays of energy disappearing into a fissure in the rock.

“Interpretation is difficult because these works emanated from the mind of each individual painter,” said Ndzima. “What was being painted were such unique experiences that only the shaman who travelled to the spirit world really knew.”

Bassett said he is similarly cautious of attempting to explain the paintings definitively, although he says there’s most likely some merit in the idea that these paintings were essentially a portal to another dimension, a means of gaining access to a kind of mirror image of our own world, a heightened reality, perhaps the spirit world that existed on the other side of the rock.

“For the artists, reality didn’t end at the surface,” said Bassett. “There was a world behind the rock as well.” Their paintings, which connect the viewer not only with the rock’s surface but also with the realm beyond the surface, are an expression of that immersive cosmology. DM

You may write a letter to the DM168 editor at heather@dailylmaverick.co.za sharing your views on this story. Letters will be curated, edited and considered for publication in our weekly newspaper on our reader’s views page.

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R35.

Stephen Townley Bassett and Londi Ndzima at Fallen Rock Shelter. (Photo: Keith Bain)

Stephen Townley Bassett and Londi Ndzima at Fallen Rock Shelter. (Photo: Keith Bain)