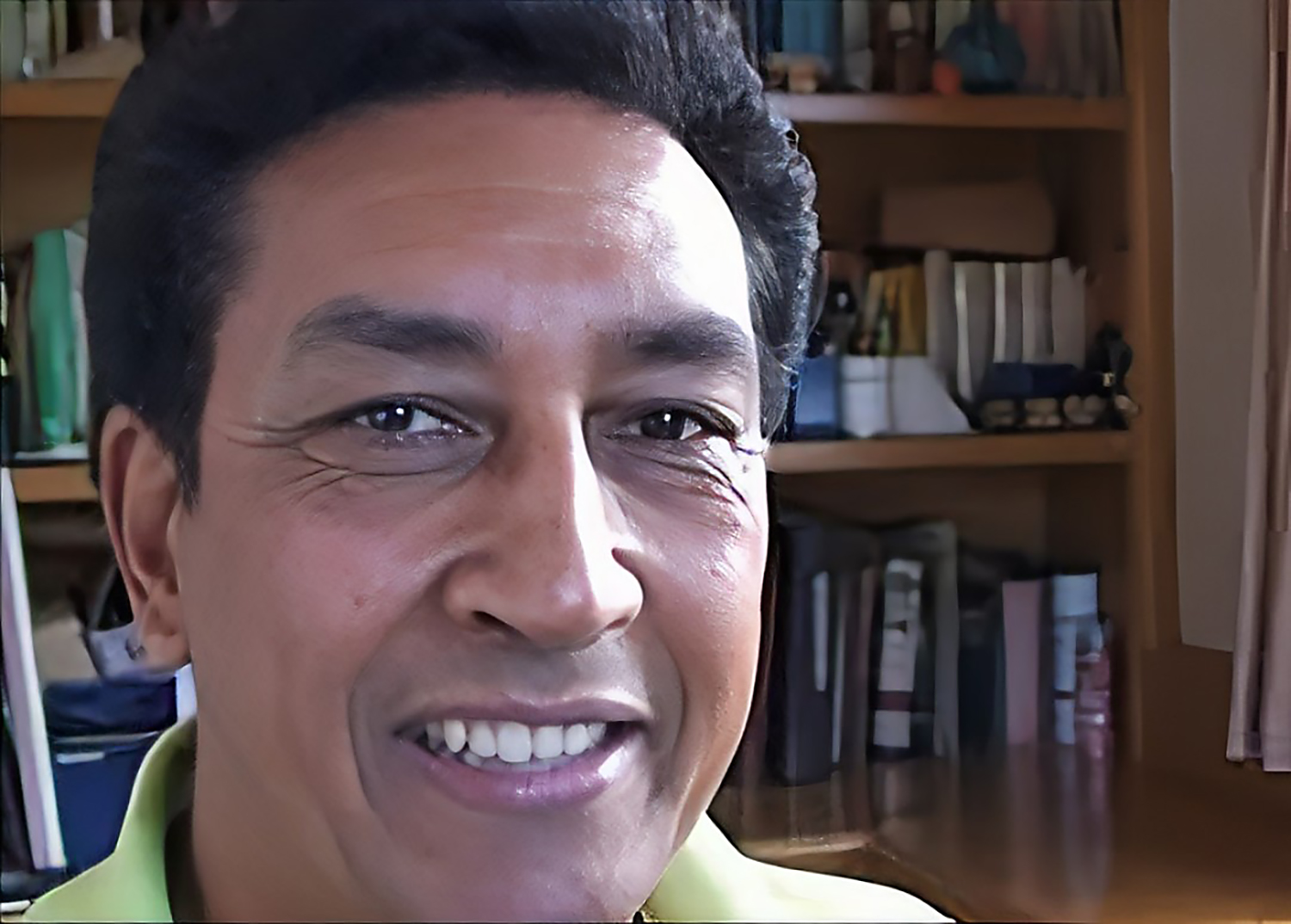

He had a way about him, wise, knowledgeable, with an ironic – at times wicked – sense of humour. His father was Sydney Vernon Petersen, the well-known Riversdale-born educationist and exceptional and searingly melancholic poet of the Afrikaans language, and principal of the remarkable Athlone High School located in Silvertown, Cape Town.

Sydney Jnr was five years my senior and matriculated before I joined Athlone High in 1966. I hadn’t really known him, but over the past decade I saw him on and off. Sydney died recently at the age of 76. I write this as a tribute to a special man from a special family having lived through a special time.

A year ago, Sydney Jnr asked me to prepare a preface to a book he was writing. The draft I read was a record of his life and times in a corner of a Cape Town suburb called Black River.

At first glance it appeared to be a parochial story about a sliver of Cape history. Not so: instead, we learn about how Black River was part of a precolonial history of cattle grazing in a setting stretching under the shadow of the majestic Table Mountain; how it bordered on the great wetlands of what became known as the Mowbray Golf Club, and by the Rondebosch Common bequeathed in perpetuity by Cecil John Rhodes to Cape Town’s citizens.

Black River was the passage between the earliest colonial settlements and the sandy expanses of what became known as the Cape Flats, the place where Cape Town’s people classified as “coloured” ended up living in largely dormitory suburbs.

I recognised so many of Petersen’s Black River references because for about two years – 1963 and 1964 – I lived there as a 10-year-old in-migrant from rural Paarl, first as a boarder with my father’s sister, Hester Kiewitz, followed by my entire family of six to live in Borden Road, about 10 houses down from where the Petersens resided.

Our move to Cape Town was prompted by the application of South Africa’s Group Areas Act of 1950, a cruel piece of legislation that created residential areas along strict racial lines (and where the state defined which “race” one belonged to).

Rural areas were hit first. Our Paarl neighbourhood was declared “white” as early as 1958 because the apartheid government anticipated less resistance there. Urban areas were within their menacing sights for mass evictions down the line in the mid-1960s, District Six and Black River included.

Group areas removals as they affected Black River are at the heart of Sydney Petersen Jnr’s memories. He records the moment his dad received a notice to vacate the family home.

Petersen Senior was a celebrated poet of the Afrikaans language, respected by many locally and internationally. He carried such a measure of respect among Afrikaans intellectuals that he could potentially have caused great embarrassment had the government decided to forcibly remove his family from the neighbourhood.

Sydney Vernon Petersen. (Photo: Supplied)

Sydney Vernon Petersen. (Photo: Supplied)

He took legal advice and stood his ground. In his draft book, Sydney Jnr documented the emotional ups and downs, the existential uncertainty, the social disruption and acute moral discomfort that arose when one retains the right to remain in one’s home while watching everyone else, including close relatives, forced to leave theirs.

Sydney wrote with great admiration about his father – who was also my school principal – and about the generations of students who pursued a classical education at the legendary Athlone High School, which Petersen Snr was asked to lead from its inception, supported by his indomitable wife Mavis (nee Hanmer).

He deliberately chose English as the medium of instruction, and had the school offer mathematics, the sciences and Latin, to equip students for acceptance in the wider world and to challenge them to pursue careers in medicine, law and the sciences that white society saw as their monopoly.

Sydney Jnr himself qualified as an architect and as an educationist. He was privileged to travel at a young age far and wide with his parents, learning how to navigate the big, wide world with confidence, unusual for anyone who lived within the suffocating confines of apartheid South Africa at that time.

Sydney Jnr’s memoir reminded me of many moments, mostly happy, of my childhood in Black River; of how he came to my rescue when my young short legs (I was 10 years old) struggled to reach the pedals of the pump-action organ of the local Chapel of St James, now demolished; of how we manually extracted the pine kernels from the trees in the neighbourhood, so easily obtained in bulk from Woolworths today; of how Christian and Muslim Capetonians lived comfortably in the shared spaces and amenities of the neighbourhood; and how children played in the streets and open spaces (there were no parks, though there could have been had the “whites-only” bowling club in Black River’s Park Road set aside some land for that purpose) with a degree of safety and security unimaginable and unheard of today.

Sydney’s death reminded me of those special times, a shared memory special to the generation that made a meaningful life despite apartheid’s restrictions. May he rest in peace. DM

Wilmot James matriculated from Athlone High School in 1970. Today he is a Professor and Senior Adviser to the Pandemic Center, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, and an Honorary Professor of Public Health at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Sydney Vernon Petersen.(Photo: Supplied)

Sydney Vernon Petersen.(Photo: Supplied)