In December 2021, South Africa’s Department of Basic Education introduced a policy mandating that schools report statutory rape when a learner under 16 becomes pregnant by an older partner.

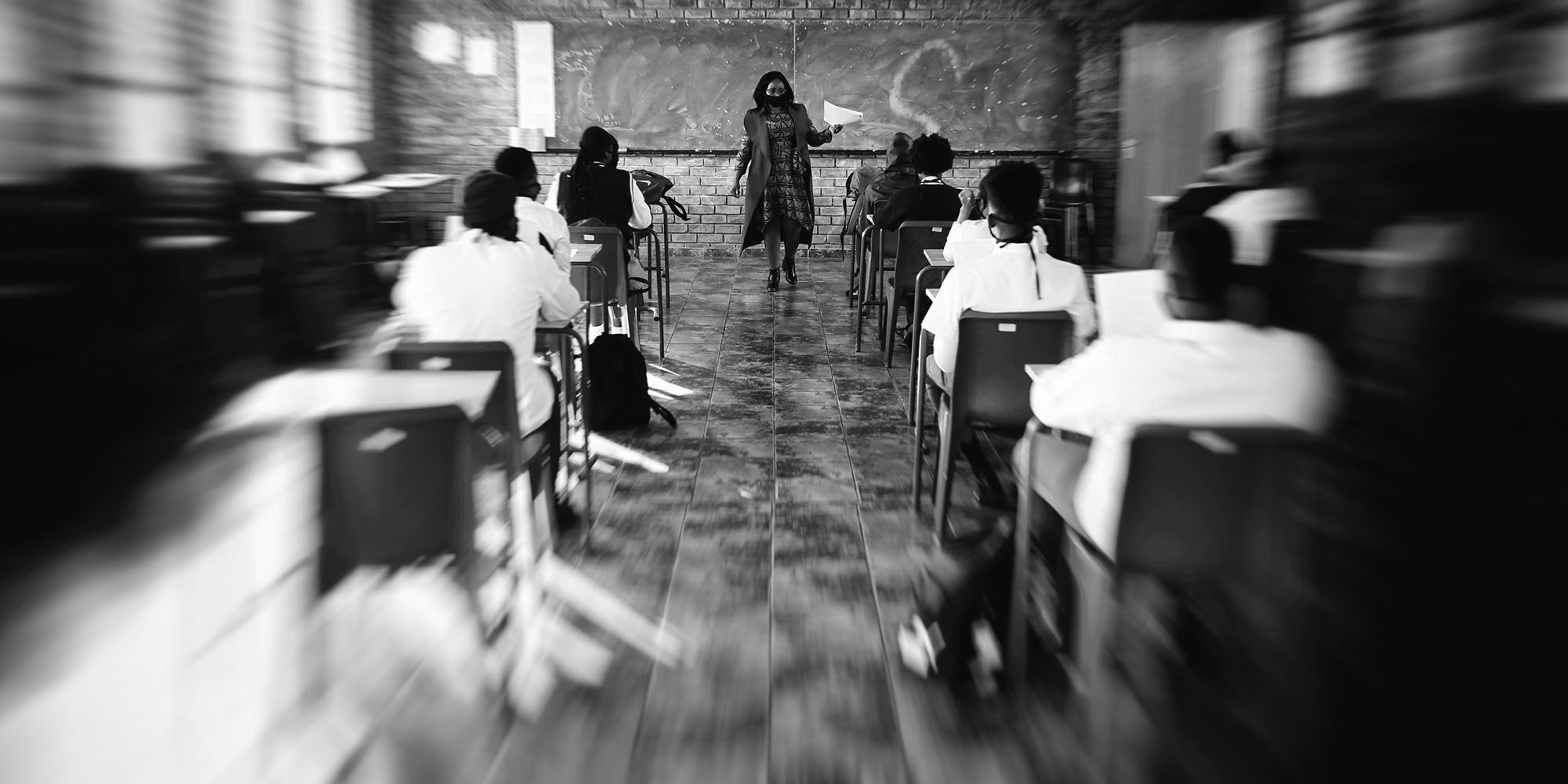

It was a decisive move aimed at protecting children in a country grappling with high rates of teenage pregnancy and sexual violence. Mandatory reporting by teachers is considered crucial in preventing and addressing statutory rape, as educators are often among the first adults to be aware of these situations and have a role in protecting vulnerable children.

Lack of training and awareness

However, recent research suggests that in many rural areas, the law is falling flat. According to the research, the implementation of this policy in rural schools faces significant barriers, revealing a gap between its intent and the reality on the ground.

A key challenge identified is the widespread lack of awareness among educators. Many teachers were unaware of the policy or unclear about their legal obligations and reporting procedures, often citing the absence of formal communication from the department.

This knowledge gap leaves teachers feeling unprepared, further contributing to the difficulties in policy enforcement.

Compounding these challenges is the critical absence of training for policy implementation. Despite the policy’s importance, teachers reported not receiving formal training from school management or government bodies. They expressed frustration at being unprepared to handle the sensitive legal and emotional aspects of statutory rape cases, leaving them feeling powerless to intervene effectively.

Daily Maverick spoke to a teacher who said she was aware of the statutory rape reporting policy introduced in 2021, but admitted she did not know how to implement it properly.

“I don’t recall us receiving formal training or clear communication about our obligations. This uncertainty and the fear that you’ll be picked on by the girl’s family for exposing such things, makes a lot of teachers hesitant to speak up,” said the KwaZulu-Natal based teacher, who asked to remain anonymous.

Cultural clash

According to the research, deep-rooted sociocultural barriers also significantly impede the enforcement of the statutory rape policy in the rural setting studied. Teachers reported community tolerance of these relationships, often linked to economic dependence on the perpetrator. Families may fear that reporting could lead to the arrest and imprisonment of a breadwinner, exacerbating financial vulnerability.

Community members, including parents, sometimes view such relationships as private matters. This creates a challenging environment where teachers fear social ostracism or backlash from families and the community if they report cases, contributing to a culture of silence.

The teacher also shared her internal conflict — that although she did not approve of these relationships, she felt it was not her place to intervene.

“It’s not my place to get involved in relationships that happen outside of school. I can tell them to use condoms, I can warn them that this older man is taking advantage of them, but I can’t physically stop it. It’s not my place, and honestly, I don’t know how,” she said.

The teacher recalled a conversation with a Grade 10 student who was involved with an older man. The student said he regularly bought her mobile data so she could video call him, but she also used that data to study. He gave her a “girlfriend allowance,” which she used to help feed her family. She was in a household of seven, surviving on her mother’s social relief of distress grant and her grandmother’s pension.

Reflecting on this, the teacher said: “How can I tell her to stop this relationship in that instance? I won’t be able to provide for her in a similar manner even if I wanted to”.

However, not all teachers share this hesitancy, with one expressing strong support for reporting and stricter enforcement of policies regarding learner pregnancies.

“These days, everything seems to be acceptable and we’re no longer firm about what’s right and what’s wrong. Behaviours that were once clearly unacceptable are now tolerated; it feels like there are no moral standards any more. What business does a 50-year-old man have with a 16-year-old? If we start accepting it, what message are we sending to the other learners?”

The teacher, who is also based in KwaZulu-Natal, explained that community norms sometimes tolerated these sexual relationships, making it difficult to report such cases without facing a backlash.

“I understand why other teachers are hesitant because many parents consider these relationships private matters and tell you to leave it alone, which adds pressure on us not to intervene. I’ve just grown a thick skin over the years. Maybe it’s because I’ve been in this profession for so long, or because I’m a senior teacher, that there’s a little more respect when I speak to guardians about these relationships,” she said.

Legal coordination gaps lead to inaction

When cases of misconduct arise, they often trigger public outrage and political promises, yet lead to little action, with teachers not always facing the consequences.

Cecile de Villiers, a labour law lecturer at the University of Cape Town, said that a fragmented legal framework in South Africa contributes to a lack of teacher accountability, particularly over sexual misconduct.

This fragmentation led to a lack of coordination between key role players, such as the South African Council for Educators and provincial departments of education, in preventing and addressing misconduct. Although sexual misconduct is a breach of both the code of professional ethics and employment rules, leading to overlapping roles, gaps exist with implications for pupil safety.

Specific obstacles include teachers resigning after misconduct, potentially avoiding reporting obligations and future employment restrictions, teachers charged with sexual misconduct not always being placed on precautionary suspension, disciplinary proceedings taking too long, and internal disciplinary inquiries being unable to make findings on a teacher’s suitability to work with children.

Different laws establish registers such as the National Child Protection Register and the National Register for Sex Offenders, but a lack of coordination means crucial information can be missed.

Bridging the gap between policy and reality

De Villiers suggested amending legislation to include clearly defined obligations and cross-references, making the sex offenders register public and better using the child protection register, addressing the resignation loophole and placing a legislative obligation on authorities to check teachers’ suitability before employment or registration.

To bridge the gap between policy and practice, the study suggests several interventions. These include:

- The need for mandatory, comprehensive training for educators on statutory rape laws and reporting responsibilities.

- Teachers also recommended establishing confidential reporting systems to protect them from potential retaliation.

- Implementing community-wide awareness campaigns to challenge harmful cultural norms, educate the community about the seriousness of statutory rape, and encourage support for teachers enforcing the laws.

- Addressing the underlying socioeconomic factors contributing to learner vulnerability, such as poverty and lack of opportunities.

- A multidisciplinary approach and contextualising policies to the realities of rural teachers for more effective implementation. DM