Perhaps there’s a book sprite that guides us, as we dither undecided at a bookshop, towards books that connect meaning to life. Or perhaps, in an era when “the wild has become the norm”, it is just a reflection of the intersectionality and interconnectedness of everything.

Let me try and illustrate what I mean.

I began 2024 reading Prophet Song, the 2023 Booker prize winner by David Lynch. It’s a harrowing feat of imagination, based on research Lynch had initially done on the civil war in Syria, transplanted to life in Dublin as Ireland slips into authoritarianism and civil war (read my review here).

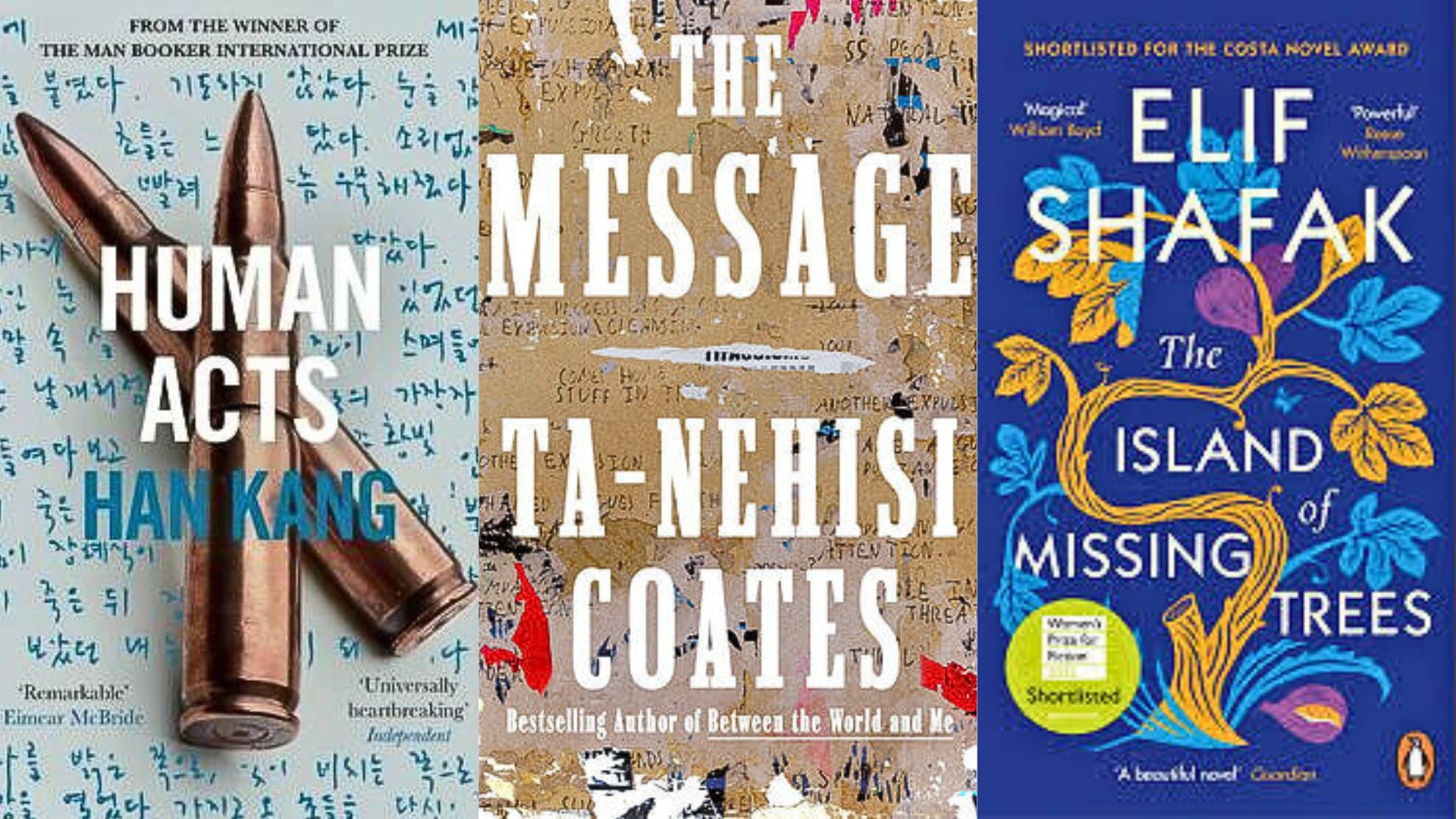

Later in the year, the news that South Korean writer Han Kang had won the Nobel prize for literature led me to several of her books, including her 2016 novel, Human Acts.

Human Acts recreates the massacre of protesting pro-democracy students by the Chun Doo-Hwan dictatorship in the South Korean city of Gwangjou in 1980, the torture of many that followed and the trauma of the survivors.

The novel centres the dead rather than the living. It is a powerful exercise in imagination over forgetting. It felt like being taken into the military hospital converted into prison and torture centre that Lynch describes in Prophet Song, where young protestors are disappeared, tortured, murdered, and from where Eilish Stack retrieves the body of her dead son, Bailey, “a place where no place can be found”.

Lest we need reminding in the time of Trump and Putin, Human Acts and Prophet Song are harrowing, evocative reminders of why the protection of human rights by international law is needed to counter man’s penchant for evil against other men, women and children.

One of Human Acts’ most troubling scenes gives life to the soul of Jeong-dae, a student shot by the police in the massacre. We listen to the thoughts of his unfettered soul as his and other bodies are transported in the back of a truck and then piled on top of each other in the shape of a cross in an army compound before being burnt.

Much later one of the students who survived the torture ruminates:

“Is it true that human beings are fundamentally cruel? Is the experience of cruelty the only thing we share as a species? Is the dignity that we cling to nothing but self-delusion, masking from ourselves this single truth that each one of us is capable of being reduced to an insect, a ravening beast, a lump of meat? To be degraded, damaged, slaughtered — is this the essential fate of humankind, one that history has confirmed as inevitable?”

One wonders.

But, I don’t think so.

How powerful is writing?

“Literature is anguish. Even small children know that.”

Talking of ghosts. Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger is a mesmerising journey through the mirror world. But I didn’t expect that it would find resonance in Ta-Nehisi Coates’ The Message, which I read at the end of 2024.

I felt as if Coates was in conversation with Klein’s anxiety about the power of words and writing in an era that is witnessing the bastardisation of truth by words used to benight rather than enlighten.

At the time I wrote a review of Doppelganger (available here) I had found it paradoxical that Klein, a prolific writer, would problematise the power of words to continue to bring about change in this era of untruth and fake news.

But Coates has no such worries: for him words, and journalism, remain a vital redoubt for those who still seek a fair, equal and sustainable world.

The second chapter of The Message, “Bearing the Flaming Cross”, describes the fall-out after Between the World and Me, Coates’ influential 2015 book, was banned by a school board in Chapin, South Carolina as part of the MAGA war against Critical Race Theory. Coates visited Chapin at the invitation of the teacher who had wanted to prescribe it and addressed the school board. In this context, he writes of writing:

“Writing and rewriting is an attempt to communicate not just a truth, but the ecstasy of a truth. It is not enough for me to convince the reader of my argument; I want them to feel the same private joy that I feel alone.”

Writers, Coates believes, “have the burden of crafting new language and stories that allow people to imagine that new policies are possible”.

“Politics is the art of the possible, but art creates the possible of politics.”

Hear, hear.

Elif Shafak: Man’s war on the environment and himself

Eight years ago I was gifted British Turkish writer Elif Shafak’s novel Forty Rules of Love. I’ve been a fan-boy ever since. I’ve caught up with her literary output. When they were published in 2019 and 2022 respectively I was ready for 10 Minutes 38 Seconds In this Strange World and The Island of Missing Trees.

So, as soon as it hit the shelves in September 2024, I pounced on her latest novel, There are Rivers in the Sky.

It’s a book that pivots on a mischievous raindrop, endlessly recycling across time and people, at a time when water wars and humans’ war on water is reaching a new height.

Shafak’s recent novels celebrate the power and sentience that inheres in nature, trees and water especially.

But, it’s not just man’s war on nature that is a recurring theme in contemporary literature, but the forever wars capitalism makes us wage on each other.

A large part of Shafak’s story is set in ancient and modern Mesopotamia, at a point of historical confluence between seemingly disassociated lives and times. The picture drawn in There Are Rivers in the Sky, particularly the genocide against the Yasidis, fictionalised the historical roots of the hatred of colonial interference and divide and rule that I had come to understand when I read BBC journalist Jeremy Bowen’s passionate history, The Making of the Modern Middle East.

The West has been interfering with and robbing the great classical civilisations and their cultures of the Middle East for a couple of centuries now. The calamitous result of our meddling is there for all to see.

As an aside, thanks to Shafak (whose character Arthur “King of the Sewers and Slums” grows up to be a genius and translates the Cuneiform tablets in the British museum). I made a detour and got myself a copy of the oldest written text in the world: The Epic of Gilgamesh is about 3,000 years old.

Reading it reminded me that humankind’s base set of emotions, and our ability to depict them in literature in a vain attempt to better understand ourselves, has been around since the advent of writing. Since then we’ve just been going in circles …

Everlasting inequality?

I have an eclectic taste for books and the novels I read in 2024 prove the point of 70s rock band 10CC in their song “Life is a Minestrone”.

My mixed masala included The List of Suspicious Things by Jennie Godfrey, Horse by Geraldine Brooks, Irvine Welsh’s latest book, Persuasion, and Graham Green’s classic Brighton Rock.

Once more connections appeared miraculously. I was given Brighton Rock after spending a few weeks in Brighton in October.

Read more: ‘Can you see the real we?’: Natural beauty, suicide and the enduring price of inequality

But unbeknownst to me when I found it in Exclusive Books a few months later, Welsh’s Persuasion is also set in Brighton, about 80 years after Green had made the English seaside resort a landmark in literature as well as life.

For the most part, Persuasion is a fast, cacophonous orgy of violence. But, as is his trademark, within its pages Welsh drops observations and insights that capture the essence of the times we live in.

For example, he comes up with one of the greatest summaries of the neo-liberal era that former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher unleashed and then departed from before seeing the full extent of the damage her dogma had done.

Describing the Brighton Marina, originally intended as a pretentious natural inlet for the rich to moor their yachts in, “as a rash of crass, shabby developments... that sprawling concrete farrago of fast-food chains and bars”, he notes: “If England’s proletariat ever gained some measure of revenge on the bourgeoisie for thirty-five years or neoliberalism, then Brighton Marina is a monument to it.”

Should I have been surprised to find that class and racial inequality, how it debases us, was a common denominator in all these novels? I don’t think so. In literature as in life.

Literature in a time of genocide

The year 2024 was overshadowed (or was it?) by the genocide being committed by the state of Israel against Palestinian people living in Gaza.

Israel’s oppression of the Palestinian people is a subject of Doppelganger, The Message and The Making of the Modern Middle East. It is also the backdrop to Enter Ghost, a novel by Isabella Hamad that made a cameo appearance on my reading list after being recommended by a friend who knows my love of Shakespeare and how the bard intrudes into the most unlikely places.

Omnipresent.

Like God.

Enter Ghost (taking its name from a stage instruction in the original text) is about a group of people who try to put on a production of Hamlet in the West Bank and how it draws together a family fractured by the Nakba. It culminates with a powerful scene of a defiant performance under the eyes of Israeli soldiers in the West Bank, bringing together literature and life, oppression and imagination, freedom and fear in a crucible of conflict and hate.

Finally — staying on the subject of Shakespeare’s afterlife in the post-colonies — one of the year’s greatest “discoveries” for me was the voluminous writing of Indian author Amitav Ghosh, a master crafter of imagination and history. After attending two lectures he gave at Wits University in September 2024 I embarked on Sea of Poppies, the first book in his Ibis Trilogy.

Sea of Poppies is an extraordinary feat of literary imagination, transmogrifying little Ghosh’s own historical research into fiction in order to reveal the disruption and dislocation caused by opium production. Following the lives and journey of Indian indentured labourers (and others) from Ghazipur to Calcutta and then on to Mauritius, it’s a tale of the hypocrisy and betrayals of the colonial elite.

As my imagination hitched a ride on the Ibis, I wondered why we, the people of the South, look so often upward and Westward for great literature when there is so much to be found to the East.

I wrote an MA dissertation in African literature, but Ghosh helped me see how narrow my exposure to post-colonial writing has been. It also made me realise how those of us who live in Africa, still smarting from slavery and colonialism, tend to overlook the damage the Western imperialist project did on other continents and to countries like India and China.

Our oppression was the rule, not the exception.

So, even in fiction (perhaps especially so) it’s hard to escape the deep questions of our time. Inequality, cruelty, injustice, wanton destruction, our loss of compassion. These are the issues that recurred in the novels I read, riffing with the realities I encountered in my day-by-day work as an activist and the non-fiction books I choose to read to improve my practice.

All the world’s a stage

And so, on this trail through writers and writing, I tripped into 2025 with the 2024 Booker Prize winner Samantha Harvey lighting my way. Her little novel Orbital brought all 2024’s themes together.

Looking down from 25 miles up Harvey sees our planet through the perspective of a multinational group of six astronauts on the International Space Station as it circumnavigates the world 16 times in one day.

Despite their distance from earth the six astronauts also circumnavigate a full gamut of human emotions. They contemplate our destructive behaviors with the benefit of high-sight.

When they look at the planet it’s hard to see a place for, or trace of, the small and babbling pantomime of politics on the newsfeed, and it’s as though that pantomime is an insult to the august stage on which it all happens, an assault on its gentleness, or else too insignificant to be bothered with. They might listen to the news and feel instantly tired or impatient. A litany of accusation, angst, anger, slander, scandal that speaks a language both too simple and too complex, a kind of talking in tongues, when compared to the single clear, ringing note that seems to emit from the hanging planet they now see each morning when they open their eyes. The earth shrugs it off with its every rotation.

Except, as Harvey reveals, the earth doesn’t shrug it off.

Looking down the astronauts notice the signs of how our politics “has sculpted and shaped and left evidence of itself everywhere… The planet is shaped by the sheer amazing force of human want, which has changed everything…”

Hear hear, again.

If you want to understand just how much damage we are doing read South African writer Adam Welz’s End of Eden, a book that finds rapture in the wonder of nature, but expresses solastalgia about how we are breaking it down. A call to arms.

Read more: ‘End of Eden: Wild Nature in the Age of Climate Breakdown’

We, the universe’s hollow men, have done outsize and irreversible damage to our only home and everything we share it with. In fact, hard though it might be to contemplate, we are a species whose extinction might be a good thing and benefit a million others.

In my view Orbital is a work of fiction that will come to be seen as much of a stake in the sand of our times as Orwell’s prophetic 1984 was in 1948.

Hope and solidarity

To be or not to be, that has become an existential question.

So, if politics has become so destructive, in the face of so much danger to people and planet, what can people do? As someone committed to a fairer world, I’m always on the lookout for books that offer insight and ideas on social justice struggles and activism, and 2024 offered a significant harvest.

For example, Vincent Bevins’ If We Burn is a interview-based analysis of 10 protest movements that shook the world — but didn’t change it — over the past decade. It begs hard questions about the shortcomings of activism, reminding activists that “failure is an option”.

Read more: Protest movements that shook the world but didn’t change it

As if to answer some of the challenges posed by Bevins, came two other new books: Solidarity: The Past, Present and Future of a World Changing Idea and Practical Radicals: Seven Strategies to Change the World.

Both are written by activists-cum-academics, with decades of experience in campaigns in the US. The former is a sweeping overview of the history, practice and theory of solidarity. It reminds us that a world of dog-eat-dog and dog-eat-planet, is actually not the natural order of human society.

Practical Radicals is more of a text book for activists, an attempt to talk to the moment we are in and distill lessons from success and failure in the past.

Their overarching message is the same: “Today’s movements will have to change — a lot — to rise to this moment in history. Some of these changes will require making uncomfortable and unfamiliar shifts.”

So yes, bleak as the world has suddenly become, in literature and life there is still hope. But “time’s winged chariot is drawing near”. We should all be activists now. And in order to “stay sane in an age of anxiety” (the title of a little post-Covid book by Shafak) all activists should be readers. DM

Mark Heywood is a social justice activist and writer. He recently founded the Justice and Activism Hub (JAH).