‘Go to your fax. I am sending you something that will interest you.” It was David Beresford, the Guardian correspondent in South Africa, calling from London.

The papers that rolled out of the machine did not at first mean anything to me, but on examination they appeared to show South African Police secret payments to Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s Inkatha Freedom Party.

To get the gravity of this, you need to recall the dark context.

It was July 1991, and the negotiations over the ending of apartheid were under severe threat from civil violence, particularly the war between Inkatha and the ANC in what was then called the Natal Midlands.

I was co-editor of the Weekly Mail (now the Mail & Guardian) and we were investigating and occasionally exposing what we called the “third force” – mystery forces with illicit support from within the security forces who were undermining the negotiations with partisan violence.

Their purpose was to weaken the ANC and boost their opponents. It was bloody and ugly, and although we and others were publishing exposés of this activity, the authorities and much of the mainstream media were dismissing it because the evidence was circumstantial and fragmented.

First evidence

What had come off the fax looked like the first documentary evidence of illegal state support for Inkatha. It was dynamite, if verified. It would have a major impact on the negotiations and Inkatha’s position in them.

It was also critical to our newspaper, which was battling to survive.

We were in transition from an alternative struggle newspaper to what we hoped would be a new voice for a new democracy. The censorship laws had been thrown out the window with Mandela’s release and had not been replaced, so we were revelling in our new-found freedom.

Other alternative papers were closing around us as funding ran out, and our own future was precarious. A big exposé would be the key to building a new role and identity and in getting support to survive. This might be the breakthrough we needed.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Over the phone, which was usually bugged, Beresford could not give many details other than he had received the documents from a former security policeman who appeared to be telling the truth. I had worked closely with Beresford for many years and trusted his judgement, but it would be hard to verify this material.

A team of reporters in Joburg, Cape Town and Durban, led by investigative reporter Eddie Koch, worked intensely over 24 hours to check every possible detail. We confirmed the source’s background. We checked that the names mentioned were where the documents said they were and that meetings referred to did in fact take place.

We discovered that Major Louis Botha, who was named as the go-between, was a policeman in close contact with Inkatha. There was a deposit slip for the money. We went to a bank and deposited R50 to confirm that it was an Inkatha account.

Every detail was holding up, so we were gaining in confidence. But still we were nervous. It would be typical of the security police to set us up.

Normal practice would be to put the allegations to the Minister of Police, Adriaan Vlok, for comment, but sometimes the police would then move to suppress or discredit the story. Our solution was to leave it to Beresford to go for comment and for us to publish simultaneously, so that even if they prevented our paper from hitting the streets (as they had done before), the story would be in the Guardian.

We sent it to the printer.

SABC

I had an arrangement with an SABC producer of the current affairs show Focus/Fokus to tip them off when we had a big story. The SABC was grappling with its own transition from being a voice of the apartheid government to trying out some real journalism. The old guard was still very much in control, but trying to demonstrate its independence – so there were some people at least who were keen to work with us. It was a brief window when things could happen that had never happened before at the SABC, and have seldom happened since.

The producer invited us in that night to debate the story with the police and Inkatha. When I got there, Vlok’s spokesperson Craig Kotze was waiting for me. He took one look at the front page I showed him and disappeared to make a phone call. Five minutes later, a dejected producer came to tell me that the decision to run the debate had been overridden.

When the paper hit the streets the next morning, we held our breath. Radio 702 reported it, but most other media paid little attention. If we stood alone on this, we would get chopped down. We were terrified.

Much to our surprise, Kotze issued a statement late in the afternoon confirming our story. We were deeply relieved and suddenly our phones were ringing off the hook with other media wanting in on the story.

The Saturday Star picked up on the SABC’s loss of nerve, leading the paper with an account of how I had been evicted from the studio at the last minute. Late that night, the SABC editor-in-chief himself called to ask me to come in on Sunday to debate with Vlok.

The TV debate

Distrustful of the SABC, I asked our lawyer, David Dison, to come with me. He told me to bring along copies of the documents, but I didn’t want Vlok to see how little we had: it was only a few pages.

I knew he would be off-balance if he did not know how much I had. I grabbed our entire year’s legal file, which was a thick wad of paperwork, and inserted copies of the Inkatha documents into them.

On the way, we decided that when we arrived we would set a series of unreasonable pre-conditions of the kind only ministers could make at the SABC. If they met one or two of those conditions, we would proceed.

We deliberately arrived at the studio at the last minute, and Vlok was already seated. I dumped the heavy file on the desk with a thud that resounded around the room. The minister paled.

Before we start, I said to the producer, I need to sort out some things. We will do this in English, I will be free to ask direct questions to the minister, although it would be pre-recorded, it would be shot as live and broadcast without edit. The editor accepted all the conditions without discussion.

The show began with the SABC presenter asking tame questions. “Tell me, Mr Minister, why you gave money to Inkatha” and “Isn’t it true, Mr Minister, that foreign governments give money to help the ANC?”

Then I butted in, speaking past the presenter, and began to throw questions at Vlok. Why was this secret? Wasn’t it illegal? Why were they supporting one party in the negotiations? What other support were they giving and to whom?

When the presenter tried to come between us, I waved her aside and carried on relentlessly. Vlok, having never been treated like this, was flustered. What could he deny when he didn’t know what evidence I had?

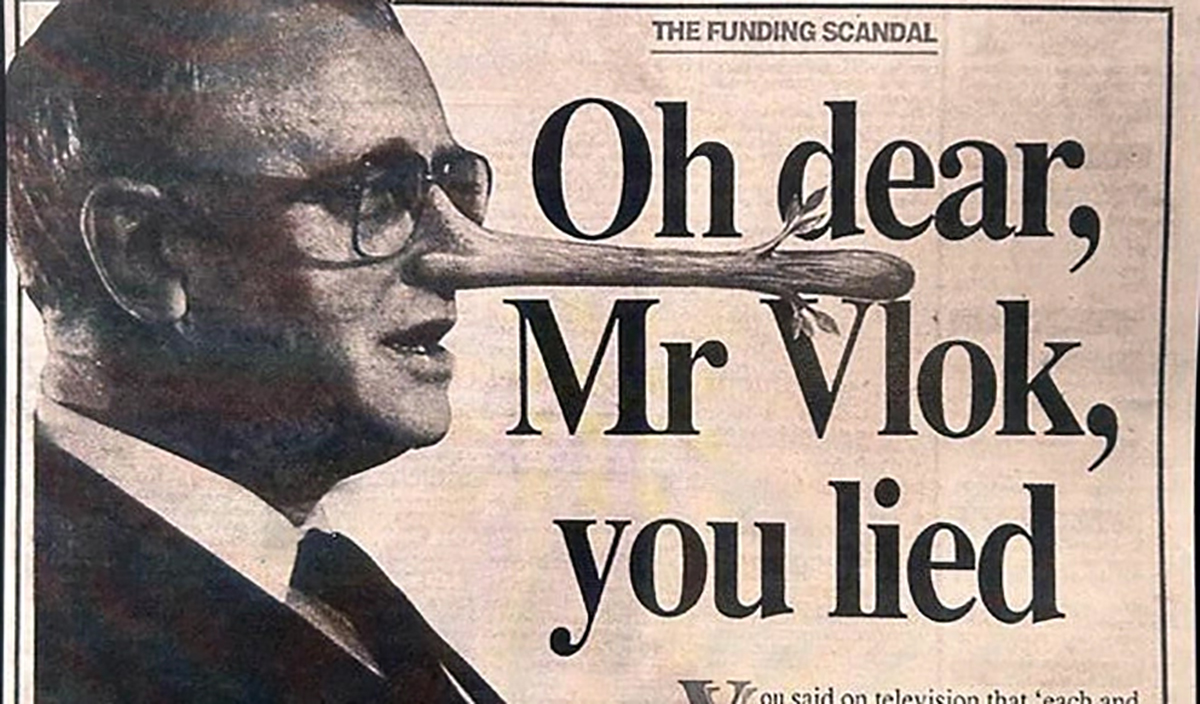

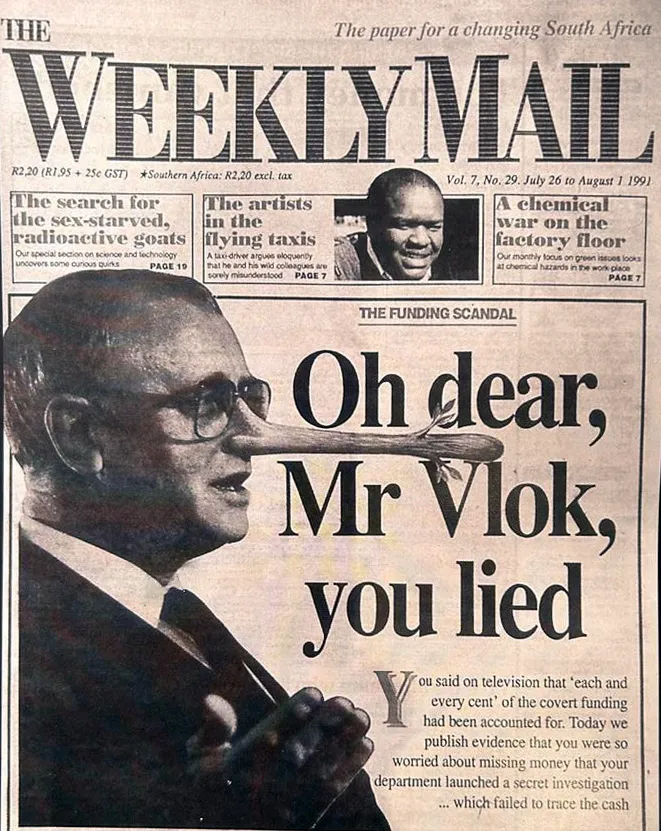

“You’re lying, Mr Vlok,” I said at one point, and pulled some papers from the file to wave in the air. “And I am going to publish the evidence next week.”

When I looked later at the papers I had in my hand, they were from an old court case, entirely irrelevant.

After the allotted 20 minutes, the producer signalled to us to wrap up. But I was at full steam and wasn’t going to let Vlok off the hook. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and I knew they could not cut it. After a few minutes, the editor was frantically drawing his finger across his throat to tell me to cut it, but I kept it going for another 12 minutes.

Finally, I said, one last question. I let a long silence hang in the air. “If we prove you have been lying, Mr Minister, will you resign?”

He stumbled. If it was shown that he had acted improperly, he would resign, he said.

It was over. A few days later, Vlok was demoted to a minor position. DM

Adriaan Vlok died on Sunday, aged 85.

Anton Harber is executive director of the Campaign for Free Expression and Caxton Professor of Journalism at Wits University.