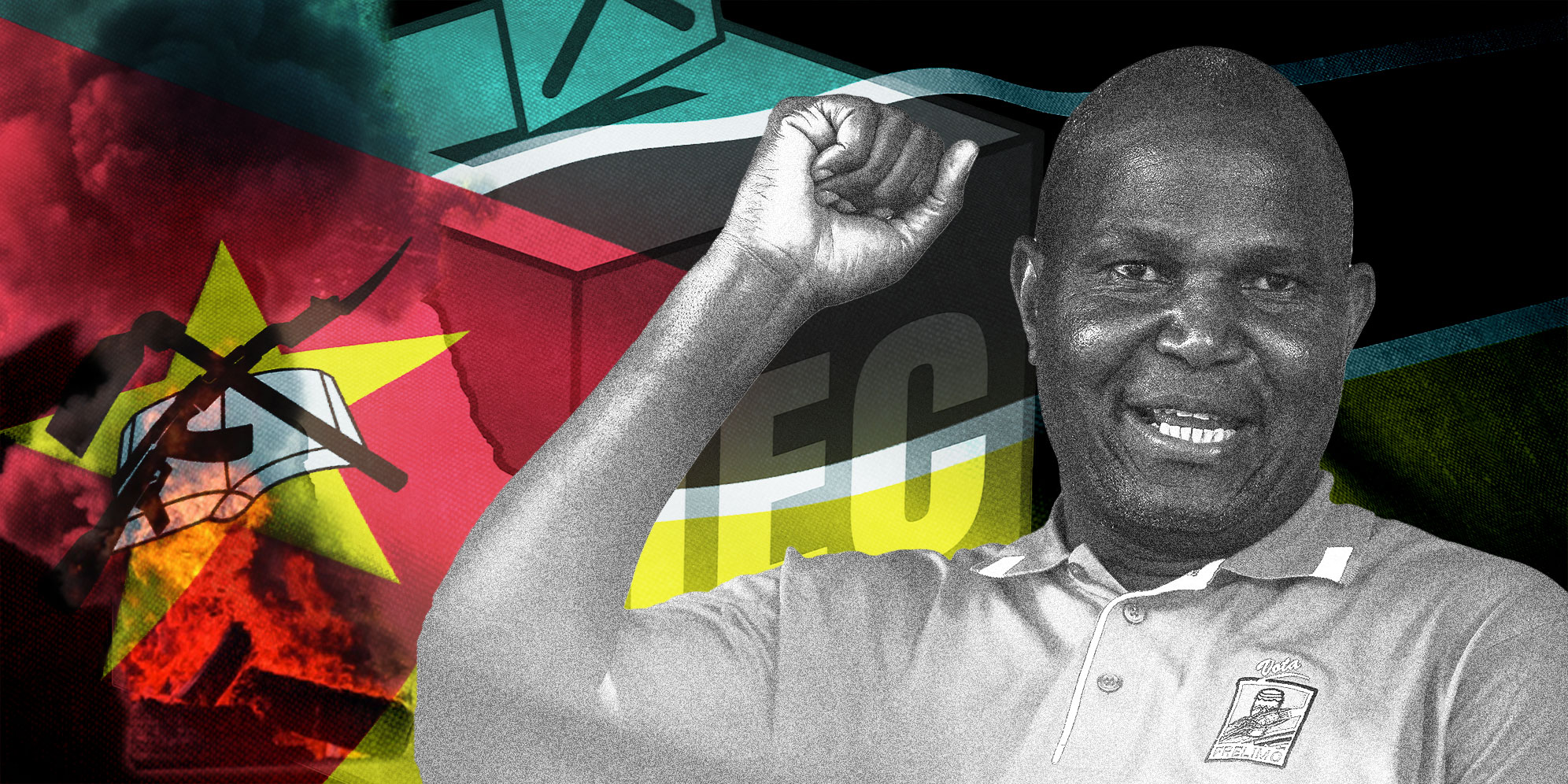

The protests in Mozambique may well be a perfect example of what can happen when citizens no longer trust their institutions.

The country’s Constitutional Council ratified the results of the election, but also changed its outcome, reducing the number of votes won by Frelimo and increasing the share won by opposition parties. But it did not provide a full explanation for this.

This was fatal. It proved to Frelimo’s opponents that the election result did not have legitimacy.

But it was also a result of a more contested political arena – Frelimo faced stronger opposition than at any time since it took power 50 years ago.

Here, where the ANC also faced its strongest opposition in 30 years, a very different outcome emerged.

Because of the strength of our institutions and that our society is transparent, it was obvious the ANC had fallen well below 50%. As a result, it had no choice but to accept the outcome (to its eternal credit) and then take the leading role in forming a national coalition government.

Read more: Quick, simple and crucial — ANC acceptance of electoral power downgrade is a gift to SA democracy

This shows how important institutions like the Electoral Commission can be.

Despite having technical problems on the day of the election, no one has brought credible evidence that could affect the outcome.

And so sure of the facts is its leadership, the commission has refused to allow MK to withdraw its case claiming that millions of votes were not counted. MK has brought no evidence of its claims.

Read more: MK tried to undermine 2024 elections — now it must pay the price in court

It is likely that over time, our institutions, both Chapter Nine institutions and our courts, will become even more important.

This is because if predictions that no political party will get above 50% again (unless our political system changes) are correct, it may be impossible for any political party to win arguments simply through Parliament.

The days when the ANC could force its MPs to defend Jacob Zuma over Nkandla or Cyril Ramaphosa over Phala Phala are now history.

In a situation where no one party, or even a group of parties, can have so much political dominance, the power of independent institutions may now start to grow.

In other words, while political parties can no longer win arguments in society through simple popular support, they will now use the law and processes to try to prevail.

And, because our politics are becoming more contested, the motivation to win attention through doing this will increase.

This means that bodies like the Public Protector, the SA Human Rights Commission, the Electoral Commission and even the Commission for the Promotion and Protection of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities (often known as the CRL) and of course, the courts, may now have more cases to deal with.

With this increased workload will come greater power. They will be making more decisions about more issues.

Also, they may face less political pressure than in the past.

During the State Capture era, Thuli Madonsela faced a very strong ANC and a powerful president. This was when ANC leaders, and a Cabinet minister, claimed that Madonsela might be a CIA agent. They had no evidence of this and none has since been presented. They were simply lying.

Read more: Thuli Madonsela: State Security Agency lied to the nation

It seems unlikely that any leader of any independent institution will be placed under such pressure again – no one has the political power.

And the process of fracturing that is under way in our politics has already led to more instances in which institutions, and the courts, had to make politically important decisions.

For example, in the run-up to last year’s elections, judges had to decide on issues around whether Zuma could be an MP and disputes between the ANC and MK over its logo.

This may just have been the beginning of a process in which our institutions are dragged into politics more often.

Contested appointments

One of the consequences of this is that the process of appointing people to make decisions within these institutions may now become much more contested.

The IEC obviously makes crucial decisions that could potentially affect the outcome of elections, the Public Protector has the power now to issue legally binding remedial action and judges routinely make decisions that have a political impact.

This means that parties may now fight harder to get people they believe support their point of view into these institutions.

But, because of the new nature of our politics, it may now be impossible for any one party to get their appointment through. Instead, parties will have to do deals with one another and find ways to cooperate.

This might mean that several parties might combine to appoint someone who agrees with their viewpoint.

But it may be more likely that instead, parties from different parts of our spectrum simply agree to make weak appointments, to appoint people who they believe will not be too aggressive or inquisitorial.

There is a very real risk here, because this could, in the much longer run, lead to our institutions losing legitimacy.

If they do not continue to enjoy the trust of South Africans and are seen to be weak or simply ineffective, they will lose legitimacy.

The result will be a situation very similar to that of Mozambique. DM