After suffering a mental breakdown and losing his job at a New York advertising agency, a young man returns to Cape Town with his husband, Adrian. It’s 2018 and Cape Town is about to run out of water. This isn’t the homecoming they dreamed of, but the couple is determined to hold on to hope. They are going to start a family by adopting a child.

But as the adoption gets under way, the narrator is forced to confront the childhood spectres he has spent a lifetime avoiding.

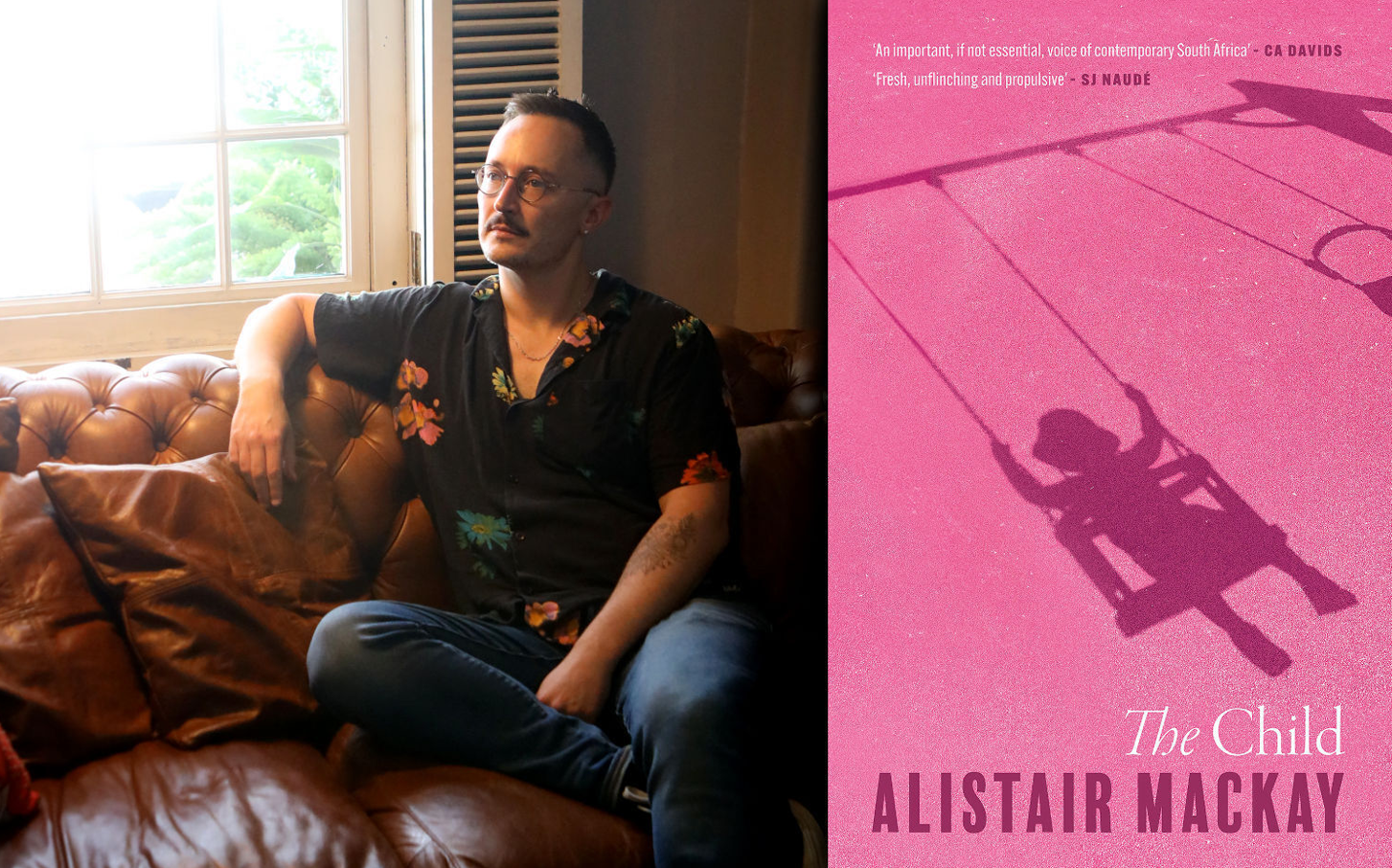

The Child is Alistair Mackay’s second novel. His first, It Doesn’t Have to Be This Way, was selected by Brittle Paper as one of the 100 Notable African Books of 2022, and was longlisted for the 2023 Sunday Times Fiction Prize as well as the 2023 British Science Fiction Association Awards. Read an excerpt.

***

Nadia asks Adrian how we met. He tells her about that birthday brunch many years ago, for a mutual friend. It’s only partially true, and I’m enjoying this: the retention of some privacy against the onslaught of Nadia’s questions. With me, she can see through my half-truths and evasion – she’s an oracle of bullshit. But with Adrian, she hangs on his every word. She likes him, and I’m enjoying this, too – seeing Adrian through her eyes. Adrian tells her about the brunch in detail. The mimosa I spilled on myself (which I had forgotten), the incredibly awkward way that we had to all go around at the table saying what we loved about the birthday boy (which I will never forget; and which is probably the reason neither Adrian nor I see that friend very much any more). He doesn’t tell her that we’d actually met the night before, at three a.m. in his hotel room. That we’d matched on a hook-up app. That he was travelling from Joburg for work and in a phase of saying yes to everything, including letting random strangers come to his hotel room at three a.m. That when we were introduced, at brunch, it was only six hours since I had left his hotel room, but we did need to hear each other’s names because we hadn’t bothered to exchange them the night before. Everyone around us could see immediately that there was something between the two of us, some inside joke.

Adrian is natural and confident as he talks to Nadia. He’s quite funny, and he knows exactly which anecdotes to tell to make us sound cute, and like we’re very much in love, and I think maybe I had forgotten that, too, or it was buried beneath the detritus of everyday life, within me but inaccessible. He’s right. We did know very early on that this was something special, and it’s still here, that flush of warmth when I watch him talk to her, that tingling gratitude that he exists, but I can’t tell Nadia this. Far too soppy.

As I’m watching him, the other thing I notice, which I must not have noticed before, not consciously, anyway, is how confident and charming he’s become. And I realise how much I have come to rely on him for this, and I experience a pang of sadness that he seems to have blossomed as I have fallen apart, as if there is only room in a relationship for one person to occupy each role. Has the strength ebbed from me to him? When I met him, there was sadness in those rich, hazel eyes of his. It was one of the things that attracted me to him most strongly – this deep, unspoken hurt. I wanted to heal it. I wanted to drive out the darkness. Instead, I’ve caught it.

But no, he hasn’t taken anything from me. His strength is not stolen; if anything, he has stepped up to help as the cracks in my imposed self-reliance started to show. We are both so different from the people we were when we met. This isn’t even the same relationship. Photographs would prove we are the modern versions of those people – that we transformed slowly, imperceptibly, that there is some continuity in character – but is it true? I read a beautiful line, once, a meme on social media I think, that all we are is consciousness moving through space and time.

All of this change and yet we haven’t drifted apart. We haven’t drifted at all. It’s a different kind of change – not movement in any direction, but beneath the skin. Or no, like moss growing on a boulder. Soil builds up in the crevices over the years, and plants with roots begin to grow in these pockets of soil, and their rotting leaves create even more soil, and more plants. Look again in ten years and the boulder is still there; there is just more life in the scene. It strikes me that I have never believed in long-term relationships. Even on our wedding day, I thought, this is great, let’s enjoy it while it lasts. You can extend the duration of any relationship with duty and obligation and guilt, but any genuine affection withers and dies. What I didn’t know could happen was reinvention. We’re in, maybe, our third or fourth relationship together, and I think this one’s going to be the closest and deepest one yet.

‘I moved to Cape Town and we moved in together within a year,’ Adrian says. ‘Like a bunch of lesbians.’ Nadia laughs.

Was the sadness I saw in him in the early years the grief that all gay men carry?

Did I project it onto him?

‘Lovely,’ Nadia says. ‘And how would you describe your relationship?’

Adrian lifts his eyebrows at me, but this warmth I’m feeling has made me passive. I don’t want to take this question. I don’t want to upset this feeling.

Adrian tells Nadia a joke. ‘One of my friends,’ he says, ‘on his parents’ thirtieth wedding anniversary, asked his mom what the secret to their marriage was, and she said to him, “We never wanted to get divorced at the same time.”’

It’s a risky joke, and the silence stretches out for the longest split-second before Nadia laughs. But the laugh is throaty. She likes Adrian. It’s all over her body language. He can tell a joke like that.

‘We also have bad timing,’ he says, and he winks at me.

And because he’s made these jokes, and it’s gone well and Nadia seems to accept, finally, that people are imperfect and relationships are messy and difficult and they can be nourishing even if they aren’t exemplary in every way, that even if you irritate each other sometimes, it doesn’t mean you’re all wrong, or that you’ll make bad parents or bad people, I feel the pressure loosen. I can breathe. And I can talk. I tell Nadia about the time Adrian lost his passport in Mozambique and we spent the whole day retracing our steps through Maputo and what started as irritation evolved into an adventure, and he tells her about the first time my mother met him and how she thought he looked like an old boyfriend of hers, and how that nearly made it impossible for me to continue seeing him, and we segue effortlessly into how we resolve conflict and how we might deal with a child who feels traumatised and abandoned by having been given up for adoption, and how we communicate when we’re under pressure and what we’ve learnt about each other since doing Myers–Briggs and Enneagram and listening to James Hollis audiobooks together on road trips, and by the end I’m thinking hey, maybe we’re quite healthy.

Except, the end isn’t the end, because the couples interview is followed by an actual personality test. Standardised, multiple choice. We separate again and spend the next hour filling in a questionnaire that is designed to pick up psychopathy.

But even the hostility of the test is not enough to ruin the closeness I’m feeling with Adrian. We stop off at the promenade on our way home. We buy gelato. He lets me taste his multiple times even though he doesn’t want any of mine. It’s coffee flavoured and he hates coffee ice cream. We walk hand in hand down the promenade like embarrassing teenagers in a world where gay teenagers can do the things that straight teenagers have always been able to do.

‘Why didn’t you just tell her we met on an app?’ I say to him when we reach the giant sculpture of sunglasses looking out to sea. ‘Even straight people do that now; it’s ordinary. She wasn’t going to think it’s sordid.’

‘Depends how many gay men she knows,’ he says. He grins at me. He’s still on a high from this whole experience and the future that it promises. ‘If she’s good friends with any gay men, she’ll think it’s sordid.’

‘Why?’

‘Because she’ll know we have the order reversed. When men and women hook up on an app, they have their date first.’

I lift Adrian’s hand in mine, and I kiss it. His smile is relaxed. He winks at me. ‘They’re looking for wholesomeness at these adoption agencies,’ he says.

‘Anyway,’ I say, ‘Nadia doesn’t have any gay friends.’

‘How do you know?’

‘She has that starstruck quality when she’s looking at you, like she can’t believe how cool you are.’

‘Psssh,’ Adrian says. ‘That doesn’t mean anything. That’s just because I’m adorable.’ DM

The Child by Alistair Mackay is published by Kwela (R335). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!

Daily Maverick’s journalism is funded by the contributions of our Maverick Insider members. If you appreciate our work, then join our membership community. Defending Democracy is an everyday effort. Be part of it. Become a Maverick Insider.