The national furore triggered by the Andre de Ruyter interview and our transition into a new era of higher-stage rolling blackouts have together drowned out the real news of the day — how the Budget Speech has changed the energy ballgame. The one glaring and hardly noticed implication of the Budget Speech is that it brings to an end Eskom as we’ve known it. Eskom’s future will no longer be about generating electricity, it will be about transmission — buying electricity from public and private entities that generate electricity, and selling it to a range of buyers including municipalities who on-sell to others, as well as thousands of businesses and households.

This, the Minister of Finance said, is part of South Africa’s Just Energy Transition strategy: “More broadly, part of addressing the persistent electricity supply shortage must involve implementing a just transition to a low carbon economy. Climate change poses considerable risks and constraints to sustainable economic growth in South Africa.

“We are also working to transform the electricity sector to achieve energy security in the long term.” This statement in the speech, supported by similar strong statements in the Budget Review, is significant and should not be ignored. If the DMRE read the speech, then the much-awaited reforms to the Energy Regulation Act (ERA) should in theory follow suit.

After months of insisting that Eskom can be fixed in 12-18 months and that another bailout is conditional on this happening, none of this bravado was present in Minister Enoch Godongwana’s Budget Speech. No mention of the 75% Energy Availability Factor that the new Eskom Board was mandated to implement. All he referred to was the need to “improve availability of electricity”. Hard to imagine how much weaker this statement could have been.

In fact, when read together with the Budget Review, his message to Eskom is very clear, to paraphrase: “rather than taking over a portion of your debt as promised in the Medium Term Budget Statement last year, we have decided to inject R254-billion into your business that can only be used to pay down your debt over three years, during which you must change your business model”. To pay for this, the debt:GDP ratio will be increased to 73.6%. In short, we will all have to work harder to pay the bill.

Sounds simple enough, but when read together with his announcements of incentives to accelerate the installation of rooftop solar and in anticipation of the forthcoming amendments to the ERA (if DMRE can get its act together), it unleashes a radical reform programme that will change the nature of South Africa’s energy sector forever.

The absence of any confident statements about the possibility of fixing Eskom’s 90 electricity-generating machines located within its 15 power stations suggests that the National Treasury has finally accepted the inevitable — there is little chance that the gradual decline of the Energy Availability Factor from a high of 90% in 2005 to below 50% in 2023 is going to be reversed anytime soon, if ever. In short, the likelihood of fixing the machines as the primary means for ending rolling blackouts is finally seen for what it is, a chimera.

The Budget Speech effectively declared that Government is no longer going to throw good money after bad. As a result, Eskom must sell off power stations that private companies will want to buy and turn around (especially those that are not too old yet), shut down those that need to be shut down in accordance with the 2019 Integrated Resource Plan, and fix what can be fixed within the financial means available (which is not much). Those who dream about restoring Eskom to its former glory as a generation powerhouse capable of ending rolling blackouts will discover that the Budget does not make provision for additional funding of a sufficient scale for this to happen in practice.

Andre de Ruyter may not have succeeded in ending rolling blackouts because he lacked the political support needed to bring the looting and sabotage of Eskom to an end, but he did succeed in setting up the National Transmission Company of South Africa (NTCSA) in line with the 2019 Eskom Roadmap. Although the Board of the NTCSA must still be appointed by the Minister of Public Enterprises so that it can get up and running as soon as possible, all the work has been done to re-allocate Eskom’s transmission assets to NTCSA, together with the related debt. The capital injection of R254-billion will obviate the need to over-burden the NTCSA with too much debt, thus freeing it up to raise the necessary capital to address the tremendous constraints on the grid. As it was put in the Budget Speech, this will enable Eskom “to invest in transmission and distribution infrastructure”. It is this stipulation that reflects most clearly National Treasury’s perspective on Eskom’s future business model. I’ll come back to this.

In July 2022 the President announced a national strategy that seemed viable at the time. Taking up suggestions by the National Planning Commission, two of the initiatives that formed part of this announcement were the following: (a) that Bid Window 6 would be increased from 2.6 GW to 5.2 GW (later reduced by DMRE to 4.2 GW); and (b) that the cap on embedded generation would be scrapped entirely.

In simple terms this refers to the following: (a) that the DMRE’s next call for proposals (i.e. the sixth call since the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Procurement Programme [REI4P] began in 2010) for renewable energy projects delivered by Independent Power Producers (IPPs) would be doubled from 2.6 GW to 5.2 GW because of the urgent need for more power on the grid; and (b) that anyone can now build their own solar or wind generation plant to generate what they need and even sell to others, no matter the size (this is what is referred to as ‘embedded generation’).

Both types of projects, however, need to be connected to the grid. Eskom responded to requests to connect to the grid on a first-come-first-serve basis. Those developers and businesses with ‘embedded generation’ projects were quickest off the mark (because of fewer hoops to jump through) and were allocated the lion’s share of the spare grid capacity. By the time the Bid Window 6 bidders got around to applying for grid capacity, all that was left was sufficient for less than 1 GW of renewables. This is what Minister Mantashe announced at the end of 2022. In short, the twin moves of lifting of the cap on embedded generation and increasing Bid Window 6 to 4.2 GW contradicted each other because of the limitations of the grid. (This could have been anticipated because information about grid limitations has been in the public domain for some time now.)

The grid has been the Cinderella of the energy system for many years. It has been neglected, and therefore there are large sections that need to be rehabilitated and major extensions are needed. Short-term measures will require investments of around R150-billion. Longer-term, to connect 5 GW per annum of renewables plus gas through to 2050 (which is what is needed), R750-billion will be required.

Visit Daily Maverick's home page for more news, analysis and investigations

There are short- and long-term opportunities. There are areas with cables, but insufficient sub-stations — this is where the quick wins lie to create new capacity in the short term. And then there are areas where no grid capacity exists, but where wind and solar resources are abundant, such as the Northern Cape. This is the challenge facing the still-to-be-properly launched NTCSA. At the moment, about 400 km of transmissions lines are constructed each year. During the heyday of South Africa’s last big build programme in the 1970s and 1980s, this build rate rose to 1200 km. To have sufficient grid capacity to connect 5 GW of new generation capacity per annum (which is what is required), the build rate will have to rise to around 2,000 km per annum. We have never achieved this before, and now we have a much more regulated environment compared to the 1970s and 1980s.

The Budget Speech and Budget Review are, therefore, completely correct in their judgement that the key to energy security in South Africa is no longer about managing the generation of electricity in a world where many private sector investors and developers are prepared to do this. Instead, the key lies in a publicly owned NTCSA that has a viable balance sheet and well-developed future planning capabilities to ensure that the supply of electricity matches the demand in the cheapest and most efficient manner. This means investing in and maintaining the grid, and buying and selling electricity at cost-reflective tariffs. Nersa, of course, will have to come to the party — but that might require a leadership that sees the future rather than the past.

Read in Daily Maverick: “25 years in the making – the real reasons we have rolling blackouts according to De Ruyter”

There has been much huffing and puffing about the reference to an international team providing National Treasury with an analysis of what was referred to as ‘Eskom’s operations’. Yes, sure, there have been similar studies done by Eskom itself (that have not seen the light of day) and by DPE. But now that National Treasury has decided on strict conditionalities for a capital injection to pay down the debt, it needs an instrument for implementing this structural adjustment strategy that provides a coherent baseline for determining what can be sold, what can be shut down, and what can realistically be fixed in the short- to medium-term.

Will selling off viable power stations to the private sector resolve the corruption and sabotage? Take Tutuka power station as an example. It is gigantic – 3,500 MW. Its Energy Availability Factor is at 30% (compared to what it should be, i.e. 90%) and it is relatively young. A private sector buy-out (probably at a massive discount given that it is basically dysfunctional in financial and technical terms) would assume a turnaround at considerable cost followed by profits for the next 20 years. The advantage that a private owner would have is that unlike a public-sector owner like Eskom that is politically micro-managed, there is no political interference in business decisions regarding staff size, management competence, security controls and procurement. This, plus a set of steel-lined gut muscles and bullet-proof vests for every manager, might make it possible to turn Tutuka around and re-establish it as a respectable employer of the people of Standerton who will then be able to start paying their municipal fees again.

When it comes to the unleashing of rooftop solar, incentives were announced for residential households and businesses. The incentive for households was for panels only. This has triggered a backlash, but it does make sense. Many households have invested in batteries, battery chargers and inverters already. They place a large burden on the national grid because after the end of rolling blackouts the batteries get charged. It has been estimated that this adds a stage to rolling blackouts. Incentivising these households to buy panels to charge their batteries can ultimately reduce rolling blackouts by a stage. Is R15,000 sufficent? Probably not.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Eskom’s ability to provide power is steadily worsening, CSIR stats show”

But it is the attractive incentive for businesses that could really make a difference. With no cap on size and a rebate of 125% of the cost, this will unleash an accelerated increase in rooftop solar installations that could make a massive difference. Vietnam did something similar in response to their energy supply crisis, and the result was the installation of 9 GW of new capacity in one year (2020)! We should not underestimate the potential of a ‘Vietnam solution’, including the unintended consequences for distribution systems and even an overshoot resulting in too much capacity.

At a recent meeting of the Presidential Climate Commission, I was asked whether it will be possible to end rolling blackouts in two years. The answer is yes, if the following materialises: if the Energy Availability Factor of Eskom’s power stations levels out at 60% (which now seems unlikely — but even 55% might do the trick); if say 6 GW of the 9 GW of embedded generation that is already in the pipeline happens quickly enough (which depends on approvals by regulators and financial institutions); if the rooftop solar revolution underway delivers at least 4 GW; if the REI4P projects deliver another 2.5 GW; if emergency gas generation is somehow brought online for a maximum of five years; if sufficient funds are available for the diesel generators; and if urgent action is taken to create more grid capacity by extending existing or building additional sub-stations where there is existing cable infrastructure. There are, of course, too many ‘ifs’ here, but this is the reality we face. Will 2023 be worse than 2022? All the evidence suggests that this will be the case. But 2024 could see an improvement if the renewable energy and gas projects come online.

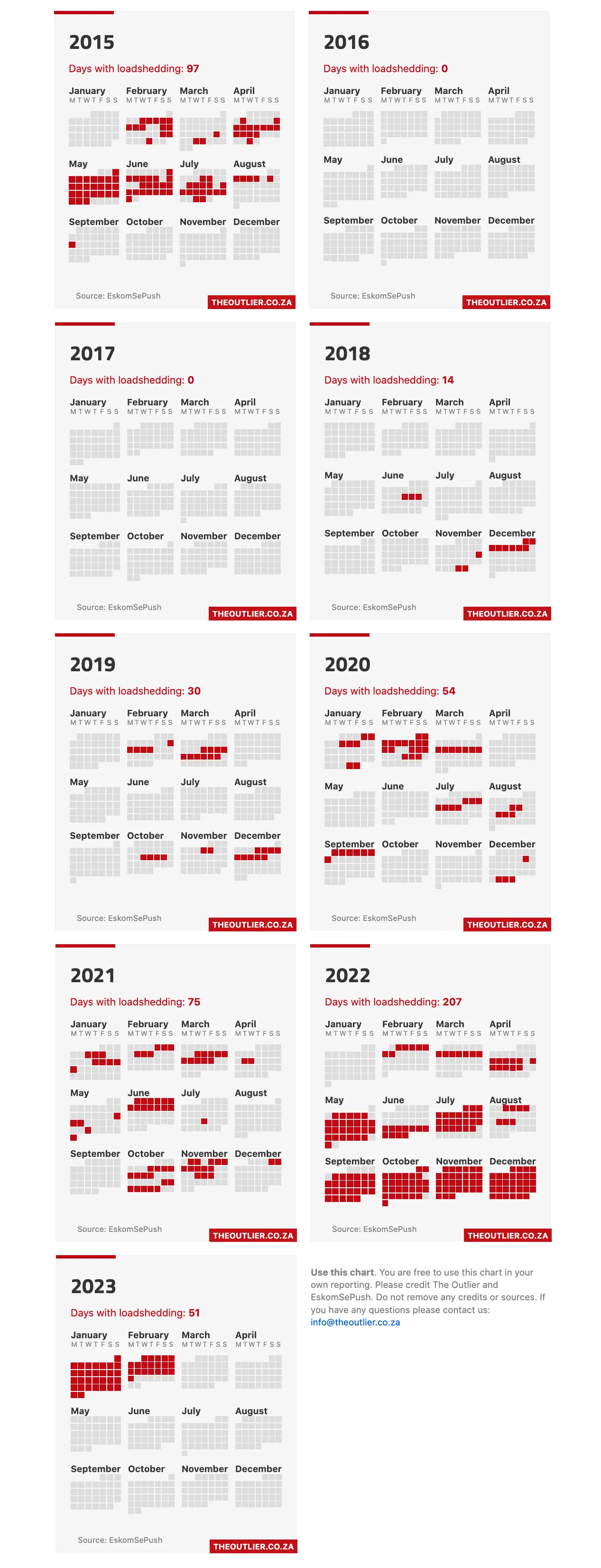

(Source: https://theoutlier.co.za/loadshedding-tracker)

(Source: https://theoutlier.co.za/loadshedding-tracker)

The Minister of Finance started his speech by referring to the energy crisis. Further, he boldly stated: “The lack of reliable electricity supply is the biggest economic constraint”. I am not sure many really understand the significance of this statement, especially those who insist that we cannot afford to transition to the cheapest source of energy available today when they earnestly insist that we need this mythical saviour called ‘baseload’. We have a baseload system now, and it is failing us.

When will we realise that South Africa has to catch up with the rest of the world by dropping this outdated concept that has no technical relevance anymore? What is relevant is the pattern and geographical distribution of demand, and how the energy system is configured to meet this demand via a vast multiplicity of electricity generators connected to a viable smart grid that can flexibly dispatch energy to where it is needed. This is what energy security looks like in the 21st century. And the driver is not attachments to technological solutions devoid of the financial costs, but rather the real cost over the life cycle and what we can afford. Why hang onto expensive technological notions like ‘baseload’ and commercially unproven ‘carbon capture and storage’ when there are proven cheaper more reliable solutions? Why? For what purpose? In whose interests?

Read in Daily Maverick: “How the ANC’s years-long delays on renewables plunged SA into darkness and scuppered plan to end blackouts”

Finally, the Budget Speech needs to be commended for emphasising and defending the now much-maligned Just Energy Transition Partnership. One of the unfortunate consequences of the De Ruyter interview is the way he cast aspersions on the JETP. His comments will influence external donors, which can set us back. There is no evidence that the governance of the $8.5-billion funding package has been diluted. Yes, true, Eskom lost control of it, but that does not mean it is under threat. This much was clarified by Commissioner Joanne Yawitch at the recent publicly broadcast meeting of the Presidential Climate Commission.

Recent revelations about the extent of corruption and sabotage at Eskom as a key driver of rolling blackouts confirm that we face some very dark and dangerous times ahead. But this should not overshadow the fact that the Budget Speech is a game changer when it comes to energy sector reform. Whether the National Treasury view of the future gets translated into practice is a completely different matter altogether. It will need all the help it can get, especially from the National Electricity Crisis Committee and key units in the Presidency such as Operation Vulindlela, the Presidential Climate Commission, the Presidential Economic Advisory Council and, most importantly, the National Planning Commission. There are some very powerful interests lined up to oppose any reforms that threaten organised looting, in particular the Just Energy Transition championed by the President and the Minister of Finance. A titanic battle for the soul of the nation is afoot. We all have a part to play in the good fight ahead. DM

Professor Mark Swilling is Co-Director of the Centre for Sustainability Transitions at Stellenbosch University.

Source: https://theoutlier.co.za/loadshedding-tracker

Source: https://theoutlier.co.za/loadshedding-tracker