The Q1:2025 Quarterly Labour Force Survey, released by Statistics South Africa today, reveals a labour market under profound stress: formal employment is collapsing, youth disengagement is rising, and long-term joblessness is becoming entrenched.

Importantly, the fairly bleak picture painted by the Q1:2025 Quarterly Labour Force Survey has yet to factor in completely the full microeconomic consequences of the battering ram of geopolitics that South Africa has been at the mercy of in the early months of this year; from tariff shocks to aborted Budgets — a cascade of disruptions whose full economic impact is still making its way through the system.

Rising population, declining participation

Consistent with previous demographic and statistical data by Stats SA, the country’s working population is growing consistently, with the current working age population having grown by 130,000 persons quarter-on-quarter, totalling at 41.7 million people.

However, the labour force itself contracted by 54,000 to 25 million within the same period, and overall employment fell by 291,000 people to 16.8 million.

It is important to note that Stats SA defines the “labour force” as both the employed and unemployed seeking work; thus, not only were jobs shed strongly through this period, but also the amount of people seeking employment at all; hinting at a far deeper challenge.

It signals a broader decline in participation — not only are more South Africans unemployed, but more are either choosing or being forced to exit the labour market altogether.

“Employment was only 43,000 higher than the same time last year,” noted Dr Elna Moolman, Standard Bank’s Group Head of South Africa’s Macroeconomic Research in a statement issued today. “These jobs were all created in the informal sector, with a rather steep decline in formal sector employment over this period.”

Read more: 62% white. 73% male. When will SA’s top management jobs move beyond the pale?

Disengagement is the job killer

The number of people not economically active (NEA) rose by 184,000 to 16.7 million. Of these, 177,000 were “other NEA” — those not seeking work for reasons such as illness, study, or caregiving. Discouraged job seekers increased by 7,000 to 3.47 million. The expanded unemployment rate rose by 1.2 percentage points to 43.1%.

Nearly half of all willing workers are without employment, yet the official unemployment rate (32.9%) significantly understates the extent of labour underutilisation.

“I think it’s about the availability of jobs that makes a lot of those discouraged seekers,” said labour attorney Avi Niselow. “The law doesn’t currently do anything to incentivise re-entry into the labour market.”

Formal sector tanks, informal can’t keep up

Formal sector employment declined by 245,000 jobs, with the largest losses being in trade (194,000), construction (119,000), and community and social services (45,000). Informal sector employment grew by only 17,000, led by transport (+67,000), finance (+60,000), and utilities (+35,000). Private household employment declined by 68,000 jobs — down 6.0% in one quarter.

The informal sector is failing to cushion the formal sector collapse. It offers no real buffer to systemic employment erosion.

“When we look at the level of employment relative to the size of the economy, we see that it is at a reasonable level when we compare it to historical trends,” Moolman said. “We now need to grow the economy to justify further employment creation.”

According to Niselow, most informal businesses already operate outside formal compliance and regulation.

“Relaxing regulations isn’t going to make that much of a difference… enforcement is its own kind of story,” he said.

Beyond the numbers, lives on hold

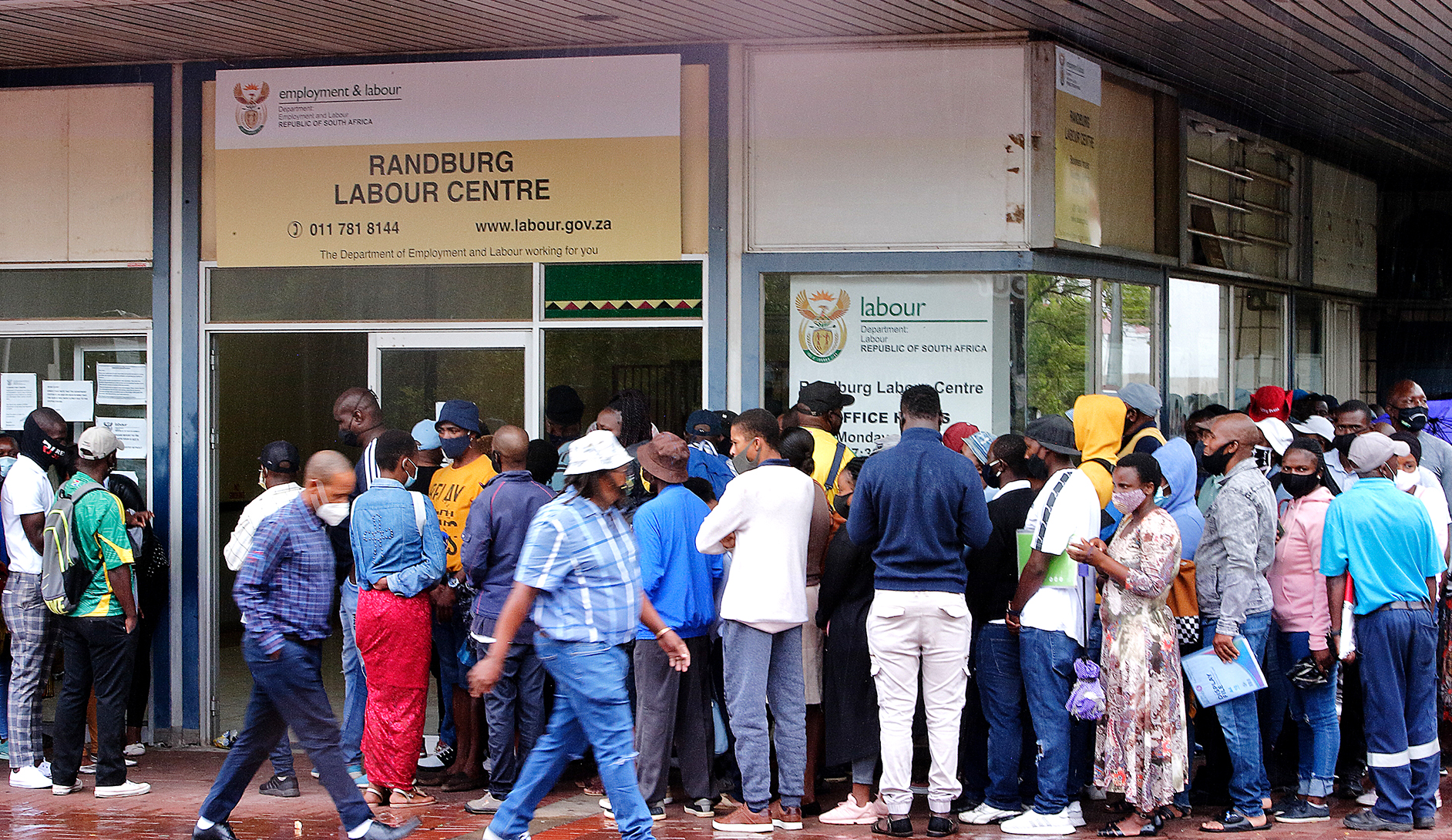

Behind the unemployment numbers lie the daily struggles of those caught in the unemployment trap.

On Monday, 12 May, a day before the QLFS stats were released, Daily Maverick visited the Department of Labour offices in Cape Town, where the human stories behind the statistics unfolded.

Before sunrise, the line outside Cape Town’s Parade Street labour centre snakes around the block. Here, hope is measured in hours spent on the cold pavement, and patience is a currency in short supply. Most of those braving the chill are young, recently unemployed, and desperate for relief from the state’s Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF). For them, waiting in line is not just about claiming money — it’s about survival amid a sluggish job market and a system that often feels indifferent.

Among those in the queue was 24-year-old Tristin Jonathan, who lost his call centre job last October after what he calls an unfair dismissal. He came to claim UIF in November, but it’s been a long wait.

“I feel like I’m walking on eggshells,” he said.

The promised two-week turnaround has stretched into months, with no payout in sight. Meanwhile, Jonathan spends hours online hunting for work, but mostly finds odd jobs — a far cry from the permanent employment he craves. For him, UIF is a lifeline that keeps slipping away and leaving him and his children struggling to get by.

Phelokazi Soyiswaphi, who lost her job when her contract ended in January, told a similar story. She claimed on 27 March, got approval on 3 April, and signed off on 14 April — but the money? Still MIA.

“I’m here today just to get an update… It’s been bad. I was used to having something to rely on,” she said.

Siphesethu Qengwa’s story adds another layer of complexity. The 28-year-old worked at Food Lovers Market for five years before resigning in November to pursue new opportunities. However, losing his ID meant he couldn’t claim UIF right away.

“I wanted to claim UIF so I could start short courses and maybe start a small business… Now I’ve finally got my ID, but surviving has been very hard.” Sometimes, it seems the biggest obstacle isn’t the job market — it’s the paperwork.

Youth lockout intensifies

Unemployed youth (15-34 years) increased by 151,000 to 4.8 million. Youth employment declined by 153,000 to 5.7 million. The Not in Employment, Education or Training (Neet) rate for youth aged 15-34 rose to 45.1% (up 1.3 percentage points year-on-year). Among youth aged 15-24, the Neet rate increased to 37.1%. The Neet rate for women is significantly higher than for men.

Nearly half of South Africa’s youth are not building skills, income, or work experience — a trend that compounds over time and feeds long-term exclusion.

“Employers are very hesitant to take on inexperienced staff members because of the difficulty in subsequently terminating the relationship,” said Niselow, pointing to one of the key legal bottlenecks preventing entry-level hiring.

A total of 76.5% of South Africa’s 8.2 million unemployed people have been jobless for one year or more. This figure stood at 63.6% in 2015 — a 12.9 percentage point increase over the decade.

The longer people remain unemployed, the harder they are to reintegrate. This level of long-term unemployment signals deep labour market scarring. DM