Learning to use numbers is a fairly recent discovery. Still today, the Hadza hunter-gatherers in Tanzania have trouble moving past three (they count “one, two, three, many”). But once we found numbers, we became obsessed with them. Humans are the species that counts.

Pre-numbers were probably notches like those on the Ishango Bone, a 20,000-year-old mammal fibula found in Congo, possibly a counting tool (they add up to 60). Maybe that’s what the scratches were on a piece of ochre found at Blombos Cave in the Southern Cape.

After about 300,000 years of scratching and notching, about 6,000 years ago a corner of our species – the Sumerians – invented a number system. A thousand years later the Egyptians decimalised their way of counting.

Further refinements came from Hindu mathematicians who invented zero and Arabs who replaced the clunky Roman numerals in general use at the time to create the symbols we use today.

In 600 BCE the Greek mathematician Pythagoras was so in love with numbers he declared them to be the building blocks of the universe.

The Ishango Bone, a 20,000-year-old mammal fibula and possibly a counting tool. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

The Ishango Bone, a 20,000-year-old mammal fibula and possibly a counting tool. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

Each step of the way has given rise to a detonation of thought. Numbers permitted better comparison between things and a way to work out how far away stuff was. Just how far, took a while to sink in.

The Greek philosopher Democritus got it right when he proposed that stars were distant suns, scattered across the vastness of space, and said some might even have their own planets. But the idea was considered so bizarre it was parked for another 2,000 years until Galileo’s development of telescopic astronomy in the 17th century. Suddenly we were a very small part of an exceedingly big universe.

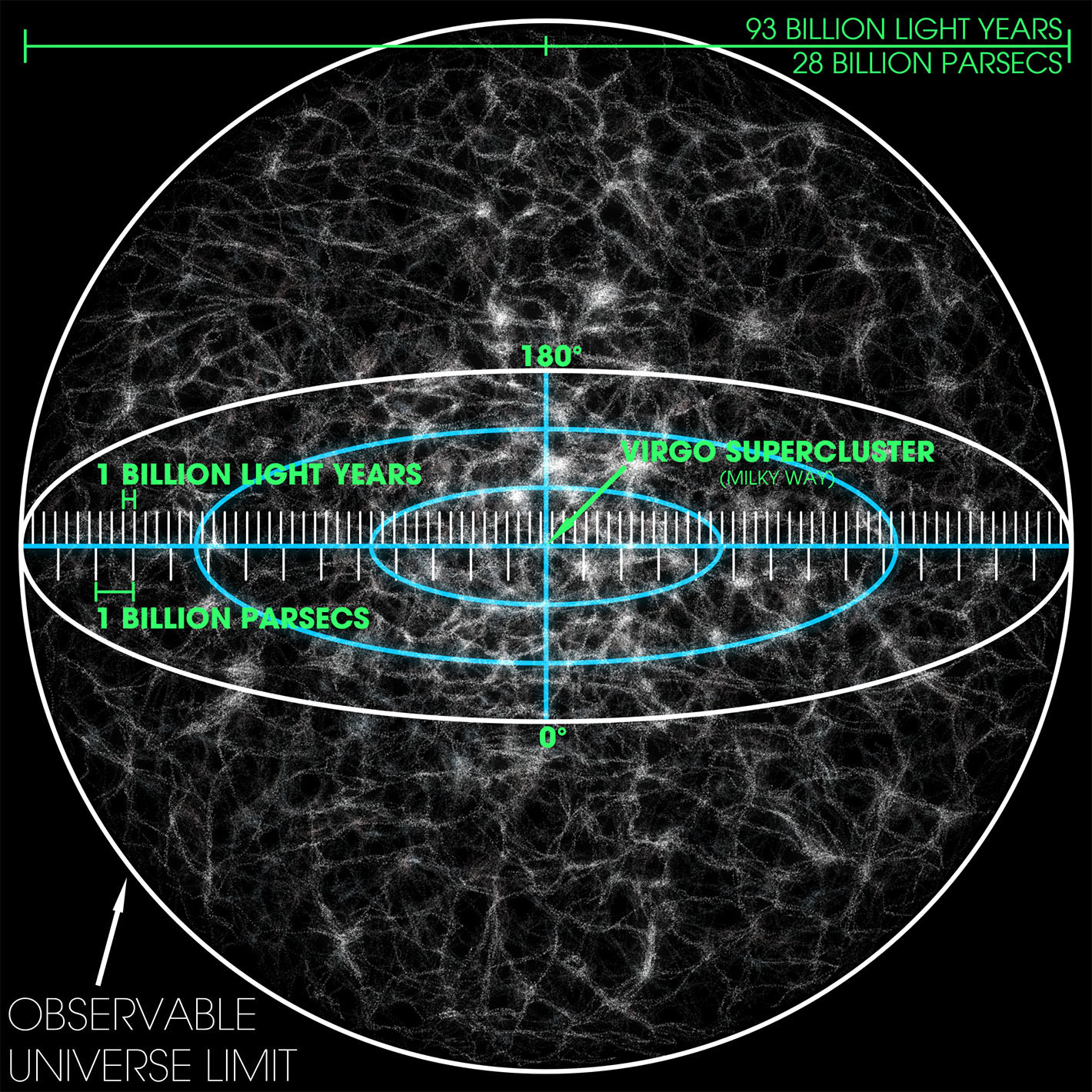

How big? In 1893, at the Harvard College Observatory, Hendrietta Leavitt worked out how to measure the distance of stellar objects. This led to Edwin Hubble being able to estimate the approximate size of the observable universe

The latest estimates are that in our little galaxy, the Milky Way, there are between 100 and 400 billion stars, but that’s just the beginning. Space telescopes tell us there are about a staggering 200 billion galaxies. Together that totals (very approximately) a billion trillion stars.

Those numbers are too overwhelming, so here’s a convenient metaphor. If every star was the size of a pea, you could cover the entire Earth with a 2km-deep layer of peas. And planets? Harder to spot, but we’ve found nearly 5,000 and counting.

Let’s go get down to Earth.

The world’s oldest mechanical calculator, invented by Blaise Pascal. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

The world’s oldest mechanical calculator, invented by Blaise Pascal. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

A Roman abacus. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

A Roman abacus. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

Around 300 BCE the botanist Theophrastus published a book, Historia Plantarum, in which he listed all the plant species known to the Greeks: 500. Aristotle did the same for the rest: 170 species of birds, 116 fish, 20 reptiles and 60 insects.

In its final edition in 1758, the Swede Carl Linnaeus listed 7,700 species of plants and 4,400 species of animals. He was largely responsible for our scientific passion for naming everything.

It’s grown some since then. The latest count is 8.7 million species scientifically listed – but that’s way under the number of species because it excludes bacteria and archaea… and everything else that’s unlisted.

In the 1970s some American scientists spread a large blanket under a massive Amazonian tree and gassed it with poison to see how many bugs would drop out of the canopy. From that single tree nearly 1,000 species landed on the blanket, many unknown.

Another Amazonian researcher, Camila Ritter, found 1,800 species in a single teaspoon of soil, most yet to be described. And then there are an estimated three million funguses.

A precursor to the pocket calculator. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

A precursor to the pocket calculator. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

Computers get a lot done in a small space with only zeroes and ones. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

Computers get a lot done in a small space with only zeroes and ones. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

With more than 100,000 species of microbes on your skin, hair and stomach, you are your own Amazonian wonderland. Bacteria co-habit our own cells and we couldn’t survive without them.

Once you tote up all Earth’s life forms, serious calculations suggest a trillion species – that’s more than the number of stars in the Milky Way. Listing them could take centuries, though climate change could drastically cut their numbers before we get to them.

Our passion for numbers satisfies a deep desire to make sense of the world and our place in it. Whether through the precision of scientific data, the abstraction of mathematical theories, or the comfort of a simple statistic, numbers shape how we understand complexity and measure progress.

They’re tools of empowerment and accountability, symbols of beauty and order and even sources of obsession. Yet, as much as we rely on them, numbers are only as meaningful as the stories we attach to them.

In the end, it is not the numbers themselves but the human imagination and curiosity behind them that truly count. We use them in everything – but they have also put us under their spotlight. Artificial intelligence is just a number system comprising ones and zeroes. Right now it’s watching us very closely to see how we think. DM

Macbook-a lot done in a small space with only zeroes and ones. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

Macbook-a lot done in a small space with only zeroes and ones. (Photo: Wiki Commons)