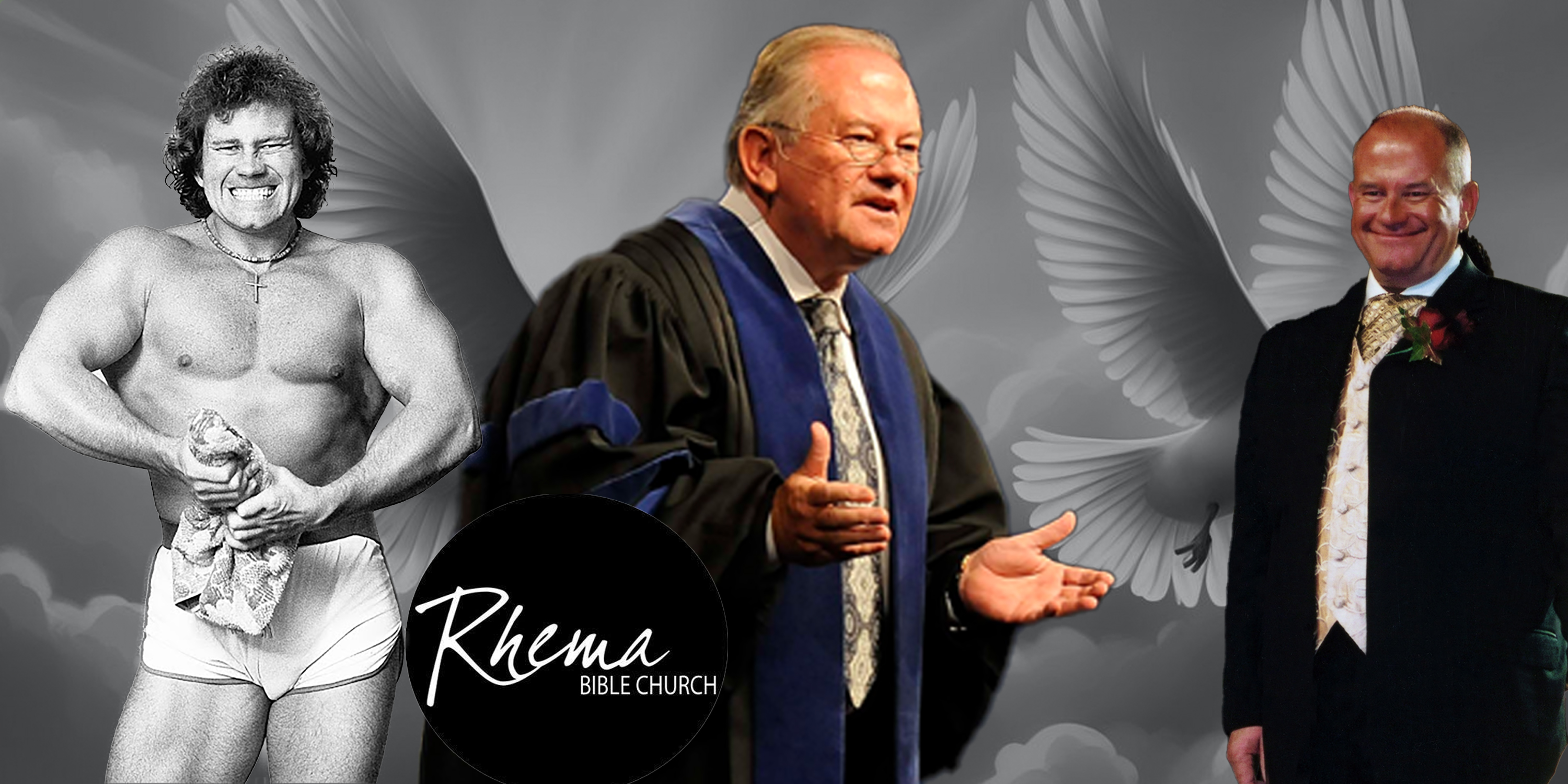

The late pastor Ray McCauley competed in the Mr Universe pageant in London in 1974 and finished in third place behind Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Ray McCauley was a courageous voice in the anti-apartheid Struggle who fought to racially integrate churches.

Ray McCauley was a loving family man whose greatest personal indulgence was a large-screen TV.

The Rhema Bible Church, founded by Ray McCauley, grew to be the largest and most powerful church in southern Africa.

All of the above has been reported as fact – in some form or another – since McCauley “transitioned to heaven”, to quote his son Josh, last week.

Those four statements are not not true. But neither are they true true, it emerges.

Indeed, if you were going to play a round of Two Truths & A Lie, you’d hate to see Ray McCauley coming. In the wake of his death, a wave of hagiography has swept the nation, with glowing tributes from musicians, sports stars, politicians; even Julius Malema, who, if we’re honest, is very rarely moved to express sadness at the death of a white South African man.

But this was no ordinary white South African man. This was Ray McCauley.

***

“He has a very pleasing physique with very good arms and shoulders. His two main problems are his legs and back, which he is presently specialising on.”

Thus ran a breathless feature on the young Raynor McCauley from a mid-1970s bodybuilding magazine, featuring photos of a bouffant-haired McCauley flexing his muscles on the beach.

“Before training with weights he was inclined to be podgy,” the magazine added, doubtless by way of encouragement to its podgy young male readers.

This was the era when McCauley hoisted dumbbells around rather than Bible stacks. It’s the period when he was competing internationally as a bodybuilder, and records show that McCauley did enter the 1974 NABBA (British National Amateur Body-Builders’ Association) Mr Universe competition.

McCauley did indeed come third – in the Tall Class 1 category of the Pro Division, behind Helmut Riedmeier of Germany and Don Ross of USA. There was no Arnold Schwarzenegger to be found there: the Austrian muscle-man was too busy winning the rival title of Mr Olympia in New York that year.

McCauley on 3 May 2010 during an interview in Pretoria. McCauley announced a day of prayer for the success of the Soccer World Cup. (Photo: Gallo Images / Foto24 / Loanna Hoffmann)

McCauley on 3 May 2010 during an interview in Pretoria. McCauley announced a day of prayer for the success of the Soccer World Cup. (Photo: Gallo Images / Foto24 / Loanna Hoffmann)

How did the idea of Schwarzenegger and McCauley going head-to-head in 1974’s Mr Universe become so ingrained in the lore of Pastor Ray that practically every obituary, following his death on 8 October, cited it as fact?

In the 70s bodybuilding magazine feature on McCauley, he further claimed that Schwarzenegger had stayed with him at his home in Johannesburg.

Did he? It’s possible they knew each other from the international bodybuilding circuit. But Schwarzenegger has spoken in public on a number of occasions about coming to South Africa in the 1960s to stay with a different bodybuilder who had moved to South Africa: the legendary Reg Park.

While we’re on the subject, did McCauley win the Mr South Africa title, as numerous obituaries in trustworthy publications have claimed? There’s no record of him on the list of winners from 1966 to 1985. Rhema Bible Church did not respond to Daily Maverick’s request for clarification on this and other points.

Do these details matter? In isolation, not very much. But what they point to, when we widen the frame, is the picture of a man who managed to cultivate an aura of such force that his personal legend outstripped the actual facts of his life by some magnitude.

***

Here’s the other thing about Ray McCauley, though: certain documented aspects of his biography are wild enough.

A 1974 press clipping headlined “The Caravan Death” opens with the following compelling sentence: “Johannesburg bodybuilder, Ray McCauley, yesterday burst into a caravan to find his fiancee unconscious next to a naked dead man”.

This is one of those stories that has to be chalked up to “it must have been a different time” – because in the current era, it would warrant a 14-episode true crime podcast at a minimum.

McCauley and his fiancee had an argument, he told the newspaper. Two days later, she stepped out with another man: Paddy Royles, the show manager of Mother Goose on Ice.

“I’m sure it wasn’t a big romance between her and that man,” McCauley said.

But the journalist recorded that Royles had been warned by his friends that McCauley was a “very jealous boyfriend”.

Tuesday night was the new couple’s second date; by Wednesday evening Royles was dead and McCauley’s fiancee – who ultimately survived – was in critical condition.

“Brixton Murder and Robbery police detectives are baffled by Mr Royles’ mysterious death,” the article read.

The same article reported that McCauley was “amateur Mr Universe, 1973”. Not according to the official results from that year – though Reg Park finished second in the pro category.

***

Some have suggested that it was this incident that pushed McCauley into the arms of the Lord; others, that it was a chance encounter with a born-again Christian at one of McCauley’s bodybuilding gyms in the late 1970s.

Whatever the spark, by 1979 Rhema Bible Church was up and running. Apartheid was still raging, pitting clerics against government authorities in an often brutal, life-endangering struggle.

But Rhema had a unique selling point. McCauley took out adverts in newspapers with the message: “If you’re tired of politics in the pulpit, come to us”.

Peter Storey, former president of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa and a perpetual thorn in the side of the apartheid government, remembers: “[Rhema was] essentially inviting white people who were angry and resentful of the fact that they were getting reminded, Sunday by Sunday, of what apartheid was doing. Anyone ministering at that time will tell you they lost disgruntled members”.

But lo…

“There was a church which wouldn’t talk about what was happening in South Africa, and that was Rhema,” says Storey.

“I used to say to Ray: You guys are the only people who can wave your hands in the air and hide your head in the sand at the same time.”

Storey’s account is backed up by numerous historical accounts of the role played by South African Christian bodies during apartheid. One such book on Evangelical Christianity describes Rhema as appealing to “young, white, and upwardly mobile city-dwellers”.

Wrote Kevin Roy in his 2017 The Story of the Church in South Africa: “There is no doubt that in his early ministry McCauley simply reproduced the doctrines of his teachers”.

Those teachers were American Charismatic Christians, who visited South Africa and invited South Africans to the USA at a time when international academics, sports teams and the like were turning the screws on South Africa as part of the apartheid boycott.

Academic and pastor Nico Horn would later write of McCauley and fellow Charismatic leaders: “As late as November 1989 they encouraged President De Klerk to maintain the ban on political organisations that had not forsaken violence” – a more conservative stance than De Klerk himself actually took.

McCauley et al also lobbied De Klerk to keep capital punishment intact, and to “reform” apartheid laws rather than repealing them. McCauley was also insistent that Nelson Mandela should state openly that he was a Christian rather than a Communist.

But one thing McCauley’s life reveals is an extraordinary ability to sniff the changes in the wind and move with speed accordingly. By November 1990, Pastor Ray would be playing a starring role at the church conference which gave rise to the famous Rustenburg Declaration, in which churches – including Rhema – asked for forgiveness for their complicity with apartheid.

On that occasion, McCauley admitted that black congregants who previously attempted to speak out against apartheid were “ostracised and rebuked”.

But by 2019, the 40th anniversary of Rhema’s founding, the re-shaping of history was complete.

McCauley and then Minister of Sport and Recreation, Fikile Mbalula at the funeral service of Jacob “Baby Jake” on December 13, 2013 in Johannesburg. The former flyweight world champion died on December 7, 2013. His funeral took place at the Rhema Bible Church. (Photo: Gallo Images / City Press / Sifiso Nkosi)

McCauley and then Minister of Sport and Recreation, Fikile Mbalula at the funeral service of Jacob “Baby Jake” on December 13, 2013 in Johannesburg. The former flyweight world champion died on December 7, 2013. His funeral took place at the Rhema Bible Church. (Photo: Gallo Images / City Press / Sifiso Nkosi)

McCauley introduces then Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa during the launch of Rhema Church’s campaign against violence towards women and children on July 30, 2017 in Johannesburg. (Photo: Gallo Images / The Times / Alaister Russell)

McCauley introduces then Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa during the launch of Rhema Church’s campaign against violence towards women and children on July 30, 2017 in Johannesburg. (Photo: Gallo Images / The Times / Alaister Russell)

President Cyril Ramaphosa addressed Rhema’s 40th birthday celebrations at an event at which then leader of the opposition Mmusi Maimane was also present.

“Since January 1979, you have been a constant and reassuring presence: taking a strong stand against apartheid and all forms of social injustice,” Ramaphosa said.

***

Does Jesus want us to be rich?

Mainstream clerics, the likes of former Methodist Bishop Peter Storey, would say no. Unequivocally.

“Jesus said it’s going to be very difficult for rich people to enter the kingdom of heaven. Jesus said: Blessed are the poor,” observes Storey.

“Jesus was crucified for taking on the rich and powerful. He wasn’t rubbing shoulders with them.”

Yet one central promise – that faith in Jesus can bring you material wealth in this lifetime – was absolutely pivotal to the wild success of Rhema once it pivoted to meet the needs of the New South Africa.

Watch a few McCauley sermons, and it’s not hard to see the appeal.

His was an earthy, colloquial preaching style with a decidedly feel-good message: All sins will be forgiven. God loves you unconditionally. Rewards await true believers in both this lifetime and the next.

McCauley borrowed his “prosperity gospel” from his spiritual mentor Kenneth Hagin, founder of the US Rhema church. Towards the end of his life, Hagin grew deeply disenchanted with the manner in which his pastor mentees had exploited this philosophy for personal enrichment, releasing a paper titled The Midas Touch in which he railed against their practices – and clarified that financial prosperity is not a sign of God’s blessings.

Other televangelists followed suit. Benny Hinn reportedly had a crisis of conscience as a result of his ministering in countries like the Philippines, where he could no longer stomach instructing poverty-stricken crowds that if they donated generously to his church they could expect to receive God’s rewards in this life.

But by the early 1990s in South Africa, the prosperity gospel was catching on like wildfire. What better theological message to catch the mood of the time? Real opportunities to financially profit off the transition to democracy, after all, were everywhere.

Rhema became the church of choice for the new black political and corporate elite in Johannesburg. There, CEOs rubbed shoulders with Struggle icons; Nelson Mandela was known to pop in during his presidency. Trevor Noah wrote in his autobiography with fondness of his experience attending the church growing up.

This was religion meets showbiz in the best Neo-Pentecostal tradition. McCauley would perform Billy Graham-style altar calls and people would stream down the aisles, propelled by the Holy Spirit.

“I witnessed thousands of miracles,” war correspondent Paul Moorcraft wrote of his time at Rhema in 1992, elaborating in the language of the time: “Cripples walked and spoke in tongues. The deaf heard; the dumb spoke.”

And everything was hi-tech: from the audiovisual system, to a stage which could expand or retract to accommodate surging crowds, to, eventually, a helipad.

“If you’re going to preach as a pastor that God wants us to be wealthy, it gives you an excuse to be wealthy,” says Storey.

McCauley told the Sunday Times in 2011 that his greatest personal indulgence was a large-screen TV.

A decade earlier, disgruntled congregants had approached the media to question how a man ostensibly living off a R20,000 monthly salary from the church could afford at least two properties with no bond, a 5-series BMW, a Harley Davidson and a Jeep Grand Cherokee.

His spokesperson said at the time: “Pastor Ray owned a couple of gyms before he started the ministry – he wasn’t poor”.

On the church website today, the Ray McCauley Legacy Fund calls on congregants to “partner your faith with your finances”.

Rhema accepts money via “INSTANT EFT, debit/credit card, Snapscan, Zapper, or even Apple Pay!”

***

At the time of his death, business records show that Pastor Ray was the director of two companies: an entity called RMCC Consulting, and a non-profit called Creflo Dollar Ministries.

Creflo Dollar is a controversial US televangelist who once asked his followers to donate money to buy him a $65-million Gulfstream private jet, and who was arrested in 2012 for allegedly assaulting his teenage daughter.

Perhaps, by this stage, McCauley was more comfortable with messy domestic situations than most men of the cloth.

After his divorce from wife Lyndie in 2000, she described her marriage to You Magazine as “emotional torture”, and McCauley as an “angry man” whose alleged abuse included removing her credit cards, threatening her friends and excommunicating a family member who helped her.

He married long-term Rhema congregant Zelda Ireland a year later, telling the Sunday Times at the time: “I’m looking forward to having a companion again. It’s been a long and lonely road”.

It is a sign of the extent to which South Africa was in thrall to Rhema by the 2000s that every twist and turn of McCauley’s personal life became tabloid fodder.

South African pastor and TV evangelist Ray McCauley and his wife Zelda Ireland. (Photo: Media 24 Pty Ltd (magazines / Gallo Images)

South African pastor and TV evangelist Ray McCauley and his wife Zelda Ireland. (Photo: Media 24 Pty Ltd (magazines / Gallo Images)

29 July 2001. South Africa. Pastor Ray McCauley and his wife, Zelda McCauley cutting the cake on their wedding day. (Photo: Joyrene Kramer / Gallo Images)

29 July 2001. South Africa. Pastor Ray McCauley and his wife, Zelda McCauley cutting the cake on their wedding day. (Photo: Joyrene Kramer / Gallo Images)

When Zelda and Ray decided to reconcile after four years of divorce, the Rhema congregation was told to remain behind after the 10am Sunday service for “important announcements”. Board members took the stage while McCauley informed the congregation of the re-marriage and was greeted with a standing ovation – and the whole story was considered significant enough to make national headlines thereafter.

It was unfortunate that his personal life failed to match the strictures of McCauley’s theology, which was adamantly anti-divorce.

But as the UK Independent noted snarkily in 2010, it gave the pastor common ground with another public figure who preached a morality he could not personally quite muster: then-president Jacob Zuma.

“When the openly polygamous president was engulfed in a scandal over fathering children out of wedlock earlier this year, the [association of churches McCauley founded and led] publicly forgave him,” the newspaper observed.

11 August 2009: President Jacob Zuma meets with the National Interfaith Leaders Council (NILC) at the presidential guesthouse in Pretoria. Left is McCauley. (Photo: Gallo Images / Foto24 / Alet Pretorius)

11 August 2009: President Jacob Zuma meets with the National Interfaith Leaders Council (NILC) at the presidential guesthouse in Pretoria. Left is McCauley. (Photo: Gallo Images / Foto24 / Alet Pretorius)

***

When the political tide started to turn against Zuma, McCauley once again shapeshifted: offering up his church as HQ to the campaign to unseat the president he had previously given access to his pulpit. Godless journalists attending Rhema premises for the first time to cover the Defend our Democracy project gawped at the scale, the spectacle, the lavishness of it all.

What, then, is the ultimate legacy of this larger-than-life South African character; the bodybuilder turned Bible-basher?

In the days since his passing, many have come forward to pay heartfelt tribute – with testimonies of how Rhema paid their rent or bought their groceries when they were most in need, and how the preaching of McCauley helped them turn a corner of some kind.

“I don’t think anyone would deny that there were people in Ray’s ministry who may have been transformed in very significant ways, and I honour that,” says Storey.

Storey points, too, to the “remarkable ministries of care” run by Rhema away from the pyrotechnics, the “flash and the fury and the razzmatazz” of the church stage. These included outreach programmes for drug addicts, street kids, alcoholics and many more marginalised groups.

McCauley leaves behind a church which, you’ll have been told many times, is the largest or the most powerful in southern Africa. This is, as with so much related to McCauley, pure hyperbole: Rhema’s congregation is dwarfed by the power of millions by a church like the ZCC.

In footage of his last sermon, given around a month ago, McCauley is seen alternately sitting behind and hunching over a glass pulpit. There was still energy there; still pulpit thumping, still that perpetual optimism that future rewards lie ahead, albeit interspersed with moments of apparent mental confusion.

“Over 20 years, I don’t know the exact time, my wife was telling me today, but it’s like 25, 30 years, I’ve been serving God…40 years, hey?” said McCauley.

“It’s been a wonderful ride, a wonderful experience. And the best is yet to come.” DM

11 August 2009: President Jacob Zuma meets with the National Interfaith Leaders

Council (NILC) at the presidential guesthouse in Pretoria. On his left is Pastor Ray McCauley, from the Rhema church. (Photo: Gallo Images / Foto24 / Alet Pretorius)

11 August 2009: President Jacob Zuma meets with the National Interfaith Leaders

Council (NILC) at the presidential guesthouse in Pretoria. On his left is Pastor Ray McCauley, from the Rhema church. (Photo: Gallo Images / Foto24 / Alet Pretorius)