The internal combustion engine is a dinosaur future generations will probably view with horror. It got us around but damn near wrecked the planet with its emissions. That much was clear to two university friends who had done innovative things with their mechanical engineering degrees after graduation.

Kobus Meiring had been programme manager in the creation of the formidable Rooivalk helicopter gunship, then moved on to manage the SA Large Telescope (SALT) being built in the Karoo. He asked his former Stellenbosch housemate Jian Swiegers to join him.

When the programme moved to its next phase – the Square Kilometre Array Observatory – they decided they needed a change. As Swiegers put it, “You only build one telescope. It’s a very aggressive race against time and exhausting.”

Liftoff

In the can-do attitude with which South Africans are often credited, Meiring suggested they build an electric car.

The pair formed Optimal Energy in 2005 with another SALT engineer, Gerhard Swart, and former helicopter test pilot Mike Lombard.

The Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) provided around R300-million and the Department of Science and Technology’s Innovation Fund added R15-million to build a prototype.

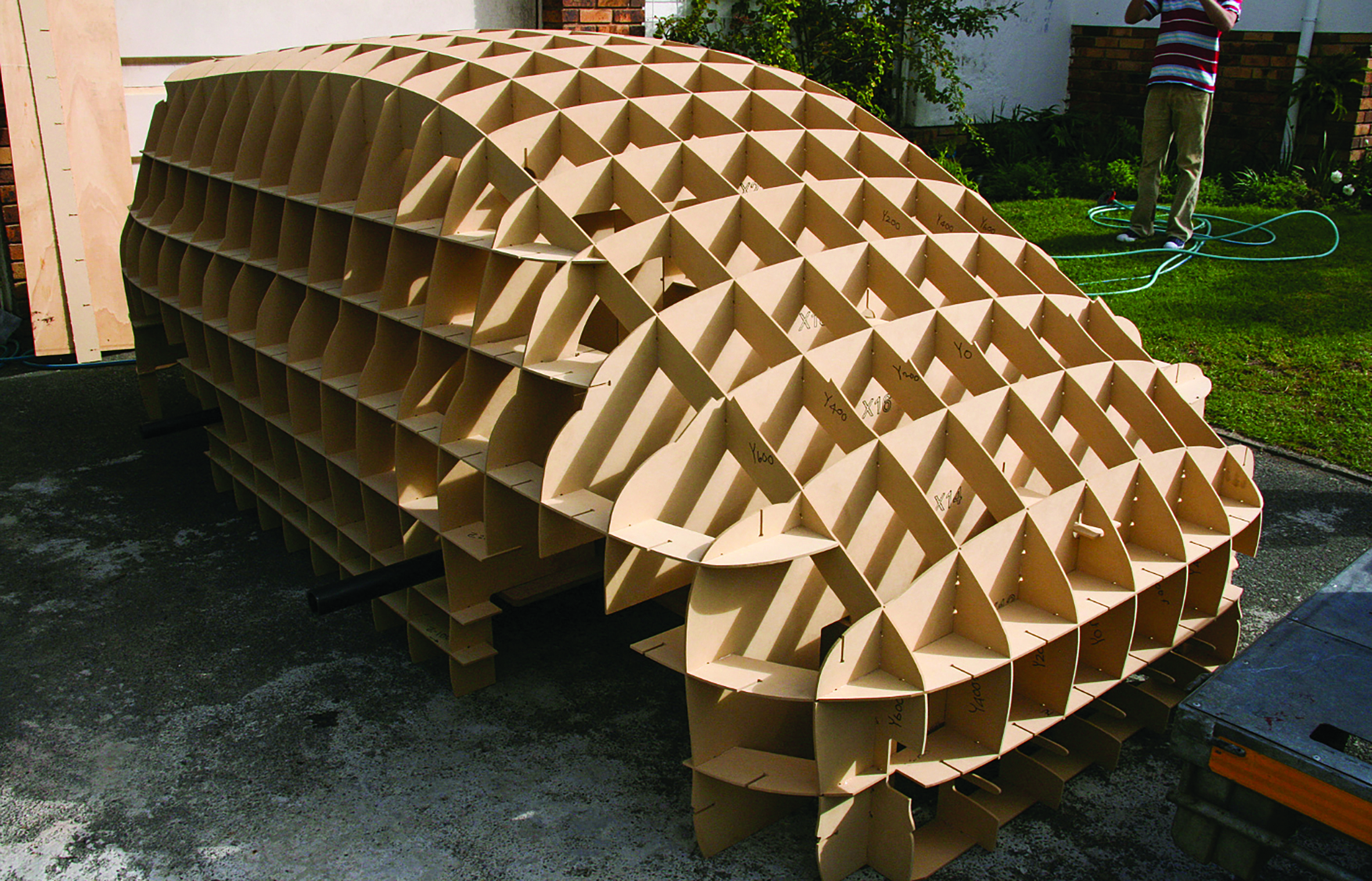

The ‘eggbox’ formation to create the prototype shell. (Photo: Keith Helfet)

The ‘eggbox’ formation to create the prototype shell. (Photo: Keith Helfet)

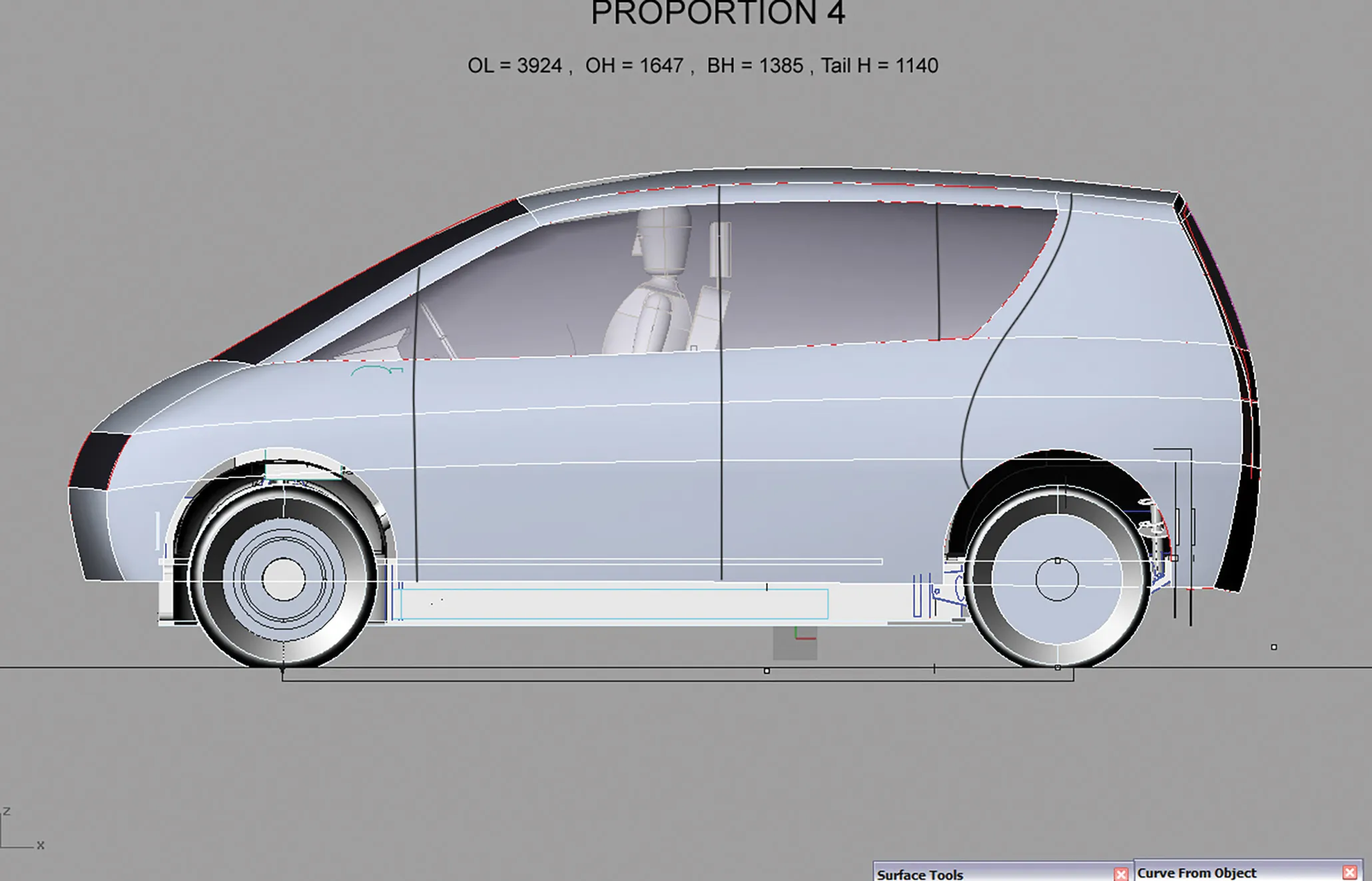

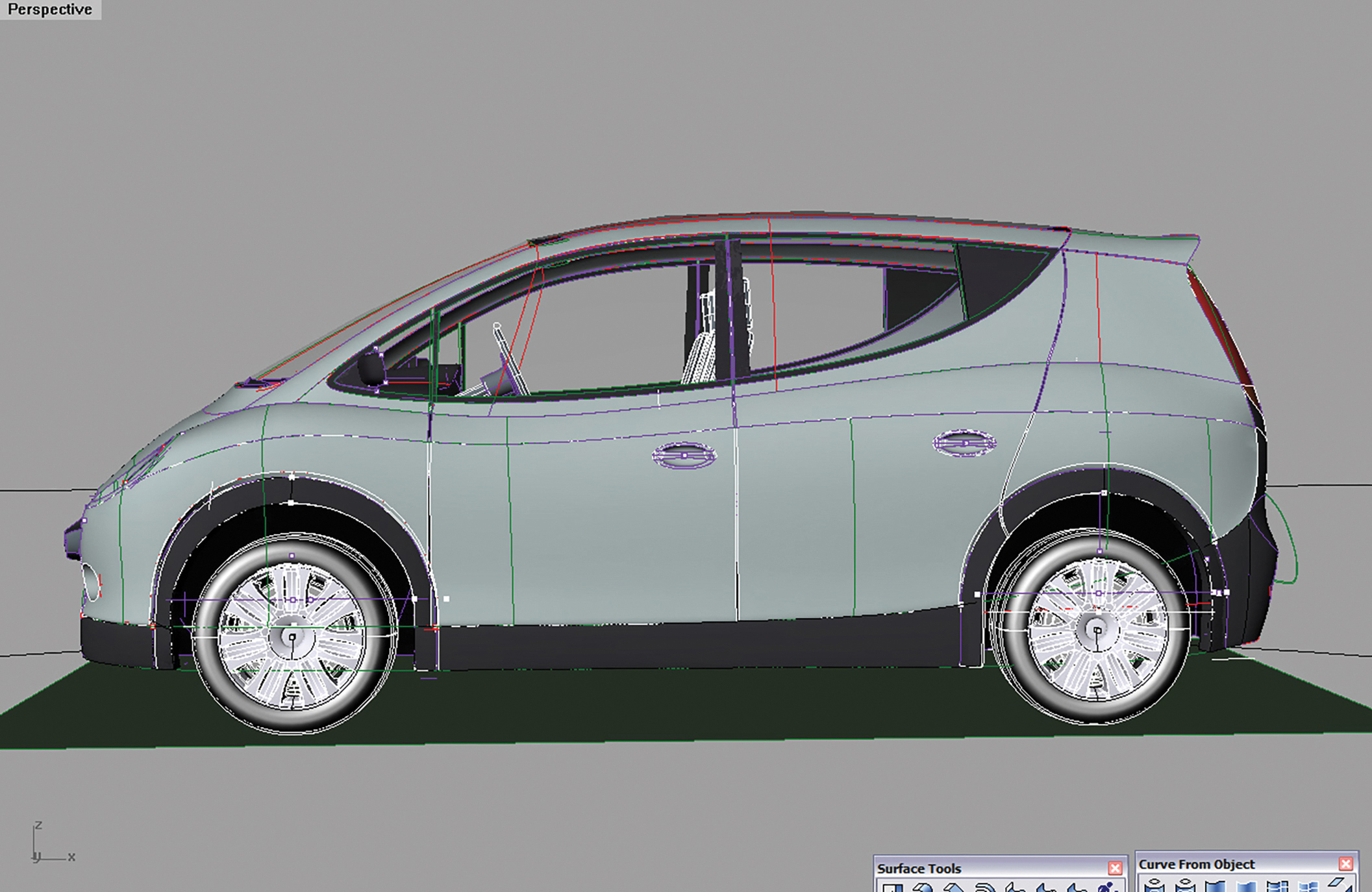

In the planning stage. (Photo: Keith Helfet)

In the planning stage. (Photo: Keith Helfet)

In the planning stage. (Photo: Keith Helfet)

In the planning stage. (Photo: Keith Helfet)

According to Swiegers, they had the good fortune to meet the chief designer for Jaguar, Keith Helfet, who was born in Calvinia, lived in Pinelands and studied at UCT. He had designed the legendary XJ220 Jaguar and other muscle cars.

“He laughed at our initial body design, but said he’d always wanted to do something in South Africa,” said Swiegers.

By October 2008, with a team consisting largely of engineers, they unveiled the Joule in shell form at the Paris Motor Show.

“The South African EV market was limited,” Swiegers explained, “so we had to aim at the budding European market. I think the timing was perfect.”

https://youtu.be/ZYoSUBxBrAk?si=FJDZcO9FSH4gO-5v

At the time, the only major car manufacturer developing a four-door EV for potential mass adoption was Nissan, which was working on the Leaf.

Tesla began production of its first EV – the two-door Roadster sports car – that same year. However, it would take another four years to mass produce its first four-door cars.

But, it appears, the timing wasn’t perfect. The show featured a high number of hybrid and electric vehicles which led a New York Times blogger to ask: “Who killed the non-electric cars?” He called them hideous.

“Only time will tell if any of these arriviste electric carmakers will ever be heard from again.”

Beside other electric vehicles at the Paris Motor Show, the Joule looked like a swan. (Photo: Supplied)

Beside other electric vehicles at the Paris Motor Show, the Joule looked like a swan. (Photo: Supplied)

In design terms, the Joule was a swan among ducklings and created a media buzz, but didn’t attract the hoped-for funding, according to Helfet. It didn’t help that it coincided with a global economic crisis flagged as the worst since the Great Depression in 1930.

The Joule’s cool interior.(Photo: Keith Helfet)

The Joule’s cool interior.(Photo: Keith Helfet)

The Joule was an EV with a Jaguar-style interior. (Photo: Supplied)

The Joule was an EV with a Jaguar-style interior. (Photo: Supplied)

Production began at a hi-tech facility near Port Elizabeth which was tasked with making a car for the forthcoming Geneva International Motor Show and four running prototypes.

The crash

At the time, Optimal Energy said full-scale production of the Joule would begin at the end of 2012, with cars in showrooms by mid-2013. It didn’t happen.

The IDC evidently got jittery. It may have been the global financial situation, a change of IDC staff which reallocated funding priorities, or the realisation that the cost of setting up production from the prototype could jump from R300-million to around R9-billion.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Lights go off on SA electric car project

“The IDC is the government body that’s supposed to invest in exactly this sort of thing,” said Swiegers.

“When they started acting in a not very constructive way, I think there must have been things happening in the background that weren’t ideal. The next step is huge. You need to understand the bigger picture and you need government support to start the motor business.

“You have to understand that you’re not going to make a lot of money early on, you need subsidies, you need support from government.”

The government was unwilling to provide the billions needed for mass production. Without government support, the Joule was dead and Optimal closed its doors in 2012.

The search

The only Joule prototypes produced. (Photo: Keith Helfet)

The only Joule prototypes produced. (Photo: Keith Helfet)

At the time there was a show “shell” and four working Joules.

A dinner-table question by one of the former engineers got our attention: “I wonder what happened to those Joules? Maybe South Africa’s first electric cars are still alive in some dark garage?”

Our Burning Planet decided to track them down.

A lead came from Jian Swiegers.

“They were built in Port Elizabeth. They were eventually donated to Nelson Mandela University by the Department of Trade and Industry.”

Their response to a request for information about the Joule felt protective:

“As starting point could please request that you elaborate on your request by answering the following questions:

- What is the objective of the story?

- Who is the intended target audience?

- What is your timeframe in terms of completing this initiative?

- What type of information are you looking for?”

Answering our response, eNtsa operations manager Nadine Goliath wrote: “The Joule vehicles associated to Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) have been decommissioned. uYilo is a national programme and currently the operational team. To my knowledge there is an automotive museum in Johannesburg that hosts one of the Joules.” She provided a web address.

That led to the James Hall Museum of Transport in Gauteng. Among the many vehicles pictured was a shiny silver Joule. Bingo! Further inquiries proved less exciting. It was the show shell. So back to Port Elizabeth.

Concerted online digging produced a photograph of three perky, colourful Joules which had been taken at NMMU; then a downer: a photo of burned-out garages. In a student demonstration, the Joules had been torched.

Burnt Joules at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. (Photo: Supplied)

Burnt Joules at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. (Photo: Supplied)

Joules before they were burnt at NMMU. (Photo: Supplied)

Joules before they were burnt at NMMU. (Photo: Supplied)

There had been four working prototypes: there was hope. Someone in the emails going back and forth mentioned that a Joule may be with the CSIR in Pretoria.

Christa van der Merwe of the CSIR was more than helpful:

“All of the Joules were donated to uYilo at NMMU. The Technical Innovation Agency funds uYilo. We recently inquired to TIA about the possibility of exploiting the Joule IP to produce vehicles in partnership with other entities. We saw a Joule at uYilo on a site visit two weeks ago.”

The last prototype. (Photo: Supplied)

The last prototype. (Photo: Supplied)

With the email came a photograph of a dull, sad-looking Joule of indeterminable colour. We sent it to Nadine Goliath of eNtsa and said we’d be in Port Elizabeth and would like to see the car. Her reply became even more protective:

“As mentioned, the vehicles associated to Nelson Mandela University have been decommissioned and not available. [Christa] upon her visit to uYilo was on an exploratory visit and images taking were not intended for further distribution and merely for knowledge transfer purposes with CSIR who our institution has an MoU/MoA which there is a clause related to NDA (non-disclosure agreement).”

Our reply was roughly: “Come on Nadine, it’s only an old car we want to look at!” Her reply bordered on bizarre:

“Let there be no allusion, I fully comprehend your frustration around not being allowed to photograph the decommissioned Joules (sic).

“We however have a responsibility to protect the historic importance of this project for South Africa and by allowing photographs going into the cyberspace of decommissioned vehicles will in our view not be fair on those who spend several years developing the Joule electric vehicles.

“As an engineering group we really respect the past and it was for this specific reason vehicles were placed in museums so people can view the final product in the original condition as was displaced internationally. I can only appeal with you to have some understanding from what our position is.”

Then the penny dropped. The university had dropped the ball in protecting the cars. Three had been burnt and the last working Joule was in poor condition and not available to nosy journalists. The “intact” Joule Nadine Goliath offered was not intact at all, but a shell in a museum.

We had finally found the last Joule – but it was in deep trouble.

Was there a solution? We asked Keith Helfet if he had any ideas.

“That’s the most ridiculous, most bureaucratic answer imaginable. We need to save that Joule.”

This is a project begging for a champion to acquire, restore and save the last Joule. Any offers? DM

The last prototype. (Photo: Supplied)

The last prototype. (Photo: Supplied)