When he died in 2014, author Chris van Wyk left behind an impressive literary legacy. The scope of his work was broad – poetry, children’s books, short stories and biographies.

But perhaps he is best remembered for his memoir Shirley, Goodness & Mercy, which chronicles his growing up in Riverlea and introduces us to the colourful characters who helped to shape his life and inform the stories he wrote.

The public persona of this witty and wise raconteur was well known, but behind it was a family man, who liked nothing better than to spend time with his sons Kevin and Karl, his wife and childhood sweetheart Kathy, and the friends and family who were his primary sources of inspiration.

Kevin van Wyk’s astute observations of his father and the strong bond they enjoyed throughout Chris’s life have resulted in a memoir that is as affectionate as it is entertaining.

In taking us into the Van Wyk household, we witness the inner workings of the mind of a storyteller, from the flowering of his father’s activism, wit and wisdom to the sources of his occasional quirky outbursts. Read the excerpt.

***

The two doctors

In less than three years I lost both my parents with virtually no prior warning, and I was left to pick up the pieces of a life without either of them. As tough as that seemed, I’ve always tried to be philosophical about it and still counted myself lucky. I had known my parents for well over 30 years and I had extracted as much from them in that time as I possibly could have done. They were both extraordinary individuals and their union in marriage made for a formidable parenting partnership.

In December 2017 I attended a graduation ceremony at Wits University. Among the many graduates being honoured on that day was my brother Karl, who would have his doctorate in English bestowed upon him after many years of toil.

Karl’s doctorate was a momentous achievement but it was also shrouded in a touch of sadness. This was the first graduation ceremony for either of us that was not attended by at least one of our parents. Our academic successes were as much a recognition of the sacrifice, encouragement and support our parents had given us as it was of our abilities. It was a team effort all round and both Karl and I acknowledged the role they played in our individual success. It was nonetheless an exceptionally proud moment, and I am confident that both my parents left this world knowing how grateful we both were for their unwavering support.

Karl’s doctorate helped him to secure a teaching position at Wits University. He had clearly inherited our father’s love of English literature and his transition into academia seemed a natural one.

Karl and I often spoke about our parents after their deaths, but the conversations were rarely, if ever, sad. The conversations always veered towards the quirky and funny moments we had shared with them. We are also two individuals who have the rest of our lives to live, and we strive to see the memories of our parents more as a means to enrich our futures as opposed to being a reminder of us having lost them at such relatively young ages.

Apart from the occasional reminiscing about our parents, every so often we received an external reminder of them. One such reminder happened in mid-2018. Karl sent me an email with a rather cryptic message: ‘See below.’

The email was an internal Wits newsletter. As I scrolled down the virtual page I couldn’t quite fathom what Karl wanted me to see. There were the usual notices about various academic departments, staff issues, recess dates. And then, almost at the end of the page, I picked up what my brother had wanted me to see: ‘Council approved the recommendation from the Senate that the following candidates be bestowed with honorary doctorates: … Mr Chris van Wyk (Doctor of Humanities – posthumous award)’. One of the foremost tertiary institutions in the country had resolved to bestow upon my father an honorary degree. As I read this my face lit up with excitement and a lump simultaneously formed in my throat.

My father did not tell stories for the recognition or fame. He told stories because of his love of reading and his desire to share and impart that love to others. My father always joked that if he wanted to become rich, he would never have been a writer. That is why so much credit must be given to my mother, who kept the steady income for the family while my father could pursue his creative dreams. His achievement was a team effort but the two most prominent components of that team were not around to savour the moment.

Despite the absence of my parents, this was a proud moment for my entire extended family and word of the honour spread quickly among family and friends. By far the best reaction came from my father’s youngest brother, Russel, who called me when he found out about the news. ‘Isn’t that amazing, Kev? Your father’s dead and he’s getting a doctorate! I’m alive and I can’t even get a matric!’ Russel may not have obtained his matric certificate, but the trademark Van Wyk sense of humour was firmly embedded in his DNA.

On the morning of Wednesday, 27 March 2019, Karl and I walked onto the stage of the Wits Great Hall along with the Chancellor, Ms Dlamini, and a host of other professors and academic staff members. We sat on the elevated stage facing the audience comprising over 200 students from various disciplines in the Faculty of Humanities, who were about to have their Bachelor of Arts degrees bestowed upon them. In the audience was our entourage, comprising Karl’s husband Trevor and his parents, Keith and Lesley, my wife Tazz and her mom, Bonnie, as well as my uncle Gregory.

When proceedings finally got under way, the dean of the Faculty of Humanities took to the podium to provide a brief biography of Chris van Wyk. He concluded with the statement: ‘Madam Chancellor, I have the honour to present the degree of Doctor of Literature, honoris causa, posthumously, to the late Mr Christopher van Wyk.’ The audience broke into polite applause as I stood up to collect the degree certificate from the chancellor. I was then directed to the podium to say a few words.

I concluded my speech with a message to the other graduates that my father would have approved of:

My father believed that people mattered. Our stories and those of our parents and grandparents who came before us are as important and valuable as any other tale. We needn’t be rich or famous to tell our stories. One of the tragedies of South Africa is that apartheid taught many of us that our stories are not important, but this could not be further from the truth. What my father had realised was that people, no matter who they were or where they came from, were proud of their stories and wanted them to be told. These people were not mere onlookers or footnotes in the history of this country but were intricately part of its story.

To the graduates, today marks a seminal moment in each of your lives. In the spirit of my father, I urge you to tell your own stories because those stories will inspire your family, friends and children – to believe in themselves by seeing what others have achieved before them. When my father died in 2014, I felt somewhat robbed. He was busy with so many other writing projects and I have this tangible sense that he was just about to reach the peak of his powers as a storyteller. Regrettably, this was not to be. This moment is also bittersweet for our family because my mother, Kathy, is also not here to celebrate in this success, having lost her own battle with cancer in 2017. She formed an integral part of my father’s career and she would be exceptionally proud of this achievement. Indeed, I would go so far as to suggest that she deserves this degree as much as he does. But their absence will not take away the immense sense of pride my brother Karl and I will carry for the rest of our lives.

Once again, to the management of Wits University, we are indebted to you for bestowing this degree on my father. Without further ado, let me now conclude my speech because, as soon as this ceremony is complete, I’ll take pleasure in updating my father’s Wikipedia page to include this esteemed honour.

Thank you!

I have often wondered what my father would have made of the world as it had evolved in the years after his untimely death. Whether it be politics, sport, science or simply listening to his fellow man, one thing I can be sure of is that it would have infuriated and excited him in equal measure. All those new experiences would have given him fodder for more stories to share with the world.

I have decided to take my father’s advice to tell stories. These are stories I remember which were inspired by my father and the ever-present rock behind his success, Katzo. I may not be able to tell a story quite like him, but one thing is for sure: he left me with the curiosity about life, which I learned from observing him for most of mine. I learned a lot more from him than I imagined, something that has been confirmed for me with each passing day since his death.

I don’t know if I have managed to discharge my mandate of proving that my father was a genius, but I’ll leave you with one last anecdote to conclude my argument.

Many years after my father had died, one of his good friends, Cyril, asked me a question I should have instinctively known the answer to: ‘How many books did your father write?’ I’m embarrassed to admit that I actually didn’t know. I quickly set about listing as many of his books as I could remember, with a little help by browsing my bookshelf and digging into the recesses of my memory. I counted 58 in all, including two that were published posthumously. That is virtually one book published for every year he was alive.

Leaving behind a legacy of 58 books, numerous essays, poetry and short stories is not a bad effort and it made me wonder how to best sum up my father’s legacy. In 2020, as the Covid-19 lockdown held the world hostage for many months, I received a phone call from Flo Bird on behalf of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. The foundation had nominated my father for a special recognition and wanted to erect a plaque outside his childhood home in his honour. On 24 September 2020, South Africa’s National Heritage Day, a small online event was held to celebrate the unveiling of my father’s plaque outside 13 Flinders Street, Riverlea. The challenge for the foundation was to capture the essence of my father’s life in less than 100 words and I think their effort was near perfect.

Chris van Wyk

The Storyteller of Riverlea. DM

Born in Soweto in 1957, Chris spent most of his life in Riverlea, publishing his first volume of poetry at the age of 22. An editor of Staffrider and Ravan Press, his first love was writing, especially for children. His poem ‘In Detention’ conjures up the evils of apartheid repression. His childhood memoir, Shirley, Goodness & Mercy, bubbles with humour and love for his mother, family and friends. A brilliant raconteur and humanist, Chris died prematurely aged 57.

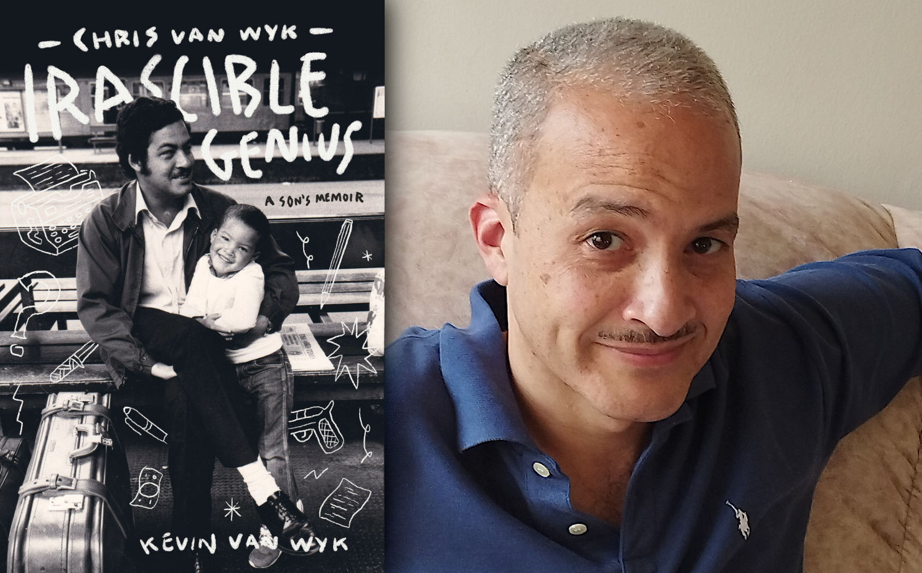

Chris van Wyk – Irascible Genius: A Son’s Memoir by Kevin van Wyk is published by Pan Macmillan South Africa (R360). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!