The space is small, filled with light and the warmth of summer streaming through long windows. On one side, books, notebooks, sketches and paintings are thoughtfully scattered, while photographs and pages seem to converse with each other; it looks like a lively family gathering. And in many ways, it is a family gathering.

On the wall, a text is pinned that reads:

These People Raised Me

These people taught me about the cosmos, about God and the good, giving Earth.

They taught me patience and to observe more than speak.

They taught me what self-discipline looks like.

I learnt curiosity, creativity and resilience can take you far.

These people’s blood runs through my veins.

Their legs are mine, their brown bodies mine too.

The grey sprouting through my black, curly hair is theirs as well.

They taught me Sa Ra Ga Ma.

Drew with me on Sunday afternoons.

They took me to the movies on Saturday mornings and down to the studio to sit for a family snap.

They showed me patience, kindness and manners is how you build character.

Dressing immaculately with freshly pressed shirts, polished, shiny shoes and folded handkerchiefs were a mark of a gentleman.

They raised me to pickle veggies and oil rice, to plant a food garden and make things.

To use my hands and my mind, that creativity is a gift and perseverance a tool.

They raised me to swim in rockpools with anemones and zebrafish,

to eat breyani on the beach on Easter Sunday.

They raised me to climb mango trees, pawpaw trees and to eat the fruit whilst sitting in a loquat tree with my cousins.

They showed me that Diwali was fireworks, new dresses and sweetmeats.

Christmas was cards with kittens, presents, watermelon and litchi feasting on the beach.

They taught me to sit patiently at the Sungum on a Sunday morning whilst my grandfather played his harmonium and to listen to his brother talk about the laws of the universe, about karma and rebirth.

They taught me to move fluidly between my Indian ethnicity and my African nationality,

to embrace my English books as education would one day be my saviour.

They taught me to think for myself and to be vocal when it matters.

These people raised me and this is me.

Kassie Naidoo in front of her exhibition, These People Raised Me. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

Kassie Naidoo in front of her exhibition, These People Raised Me. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

It is the end of February, during the Investec Cape Town Art Fair, and artist Kassie Naidoo is showcasing at Reservoir Gallery, her deeply personal work-in-progress, These People Raised Me, an ode to her ancestors, but much more than that.

Naidoo, a self-proclaimed “creative thinker, tinkerer and artist”, is also the creative force behind the aesthetic of DM168, Daily Maverick’s own newspaper. Naidoo’s experience spans roles as art director in women’s magazines, branding, design, advertising and social impact before she ventured into the world of art.

She explains that These People Raised Me was inspired by a 2016 family gathering in Durban, where one of her aunts handed each of them a copy of their grandfather’s shipslist.

“It’s a record of an Indenture Indian, with his/her indenture number and details like name, age, gender, caste, etc the British kept of every Indian sent to the colonies from 1834 to 1920. For me, it was something physical that connected me to my past,” she says.

In 2022, she took a sabbatical to dive deeper, determined to use the shipslist as a starting point in her quest to discover her true identity, an exploration to weave together the rich tapestry of her African roots and Indian ancestry.

The title, These People Raised Me, started “with a simple question, which had initially formed many years ago when I was in my garden one Joburg summer afternoon.

“How did I do what I did with my life when only a few generations before my grandparents were factory workers, porters, waiters? Over the last two years my process of fumbling my way through research, conversations, memories and photographs, my intuition, sheer luck and being able to bounce my thoughts on friends and family (mostly feels like my ancestors) led me to the working title ‘Thread’”.

Daily Maverick spoke to Naidoo about her creative process.

***

Daily Maverick: Your work beautifully weaves together ancestry, memory and identity. What was the moment or realisation that led you to embark on this project?

Kassie Naidoo: Two things actually – where did my creativity come from and where and why diabetes? I was not looking for the typical nature versus nurture narrative but something deeper, cellular, intuitive. In retrospect, it is how artists work. This was a different approach for me from what I’d done for decades, finding a creative way to solve a marketing or business challenge. It meant stretching…

CN Naidoo or affectionately called Township Thatha by the grandchildren. A factory worker, waiter, cook and entrepreneur out of necessity. A pastry chef, sweet maker and most passionately, a musician in his spare time. He played the harmonium and was the lead singer of his band, called City Orchestra. All their vinyls were destroyed in the days of apartheid as the songs in Telugu were held in suspicion for stirring up emotions and possibly seeding ideas of liberation. Collage, thread and hand-screened on paper. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

CN Naidoo or affectionately called Township Thatha by the grandchildren. A factory worker, waiter, cook and entrepreneur out of necessity. A pastry chef, sweet maker and most passionately, a musician in his spare time. He played the harmonium and was the lead singer of his band, called City Orchestra. All their vinyls were destroyed in the days of apartheid as the songs in Telugu were held in suspicion for stirring up emotions and possibly seeding ideas of liberation. Collage, thread and hand-screened on paper. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

The Strandloper: Naidoo or Town Ava. The hustle was real for my maternal great-grandmother, who raised more than 12 children, which meant doing what it took to put food on the table, from cooking lunch meals for courthouse staff to peddling handmade frames from shells picked up on the beach. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

The Strandloper: Naidoo or Town Ava. The hustle was real for my maternal great-grandmother, who raised more than 12 children, which meant doing what it took to put food on the table, from cooking lunch meals for courthouse staff to peddling handmade frames from shells picked up on the beach. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

DM: In your write-up, you speak of being “raised to move fluidly between your Indian ethnicity and African nationality”. How has this duality shaped your artistic voice?

KN: Durban in the 1970s and 80s meant growing up during apartheid so we were all being raised within entire suburbs of people just like ourselves. My Indian culture and traditions, like Diwali and Eid, Bollywood movies, clothes and community ecosystem gave me a sense of identity and belonging.

Nearly every home had a copy of Zuleikha Mayat’s Indian Delights so nearly all of us had tasted her sweetmeats, curries and samosas through her recipes our mothers and aunts followed, it connected us all.

I belonged not just to my parents but to all who fed me, scolded me or put a plaster on my grazed elbow.

My mother spoke isiZulu, having learnt it as a child from her nanny, Anna, whom she loved dearly, so as a child I heard all the gossip from the neighbouring township of Umlazi carried to my mother by the mielies and nuts makotis my mum enticed to linger longer at our kitchen door with a cup of tea and a chat.

In the evenings, I stood at the far end of our front garden, greeting everyone who walked by, especially the isiZulu and Indian men walking by after a long day’s work, with “Sawubona Baba” and “Namaste Nana”.

I was enthralled by the textures and tailoring of their clothes, elongated earlobes, beading and goat fur bangles, rubber sandals, suits and hats. For me it was this wonderful cultural borrowing and intermingling of cultures through food, music and stories.

‘My paternal grandmother showing my creative process.’ (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

‘My paternal grandmother showing my creative process.’ (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

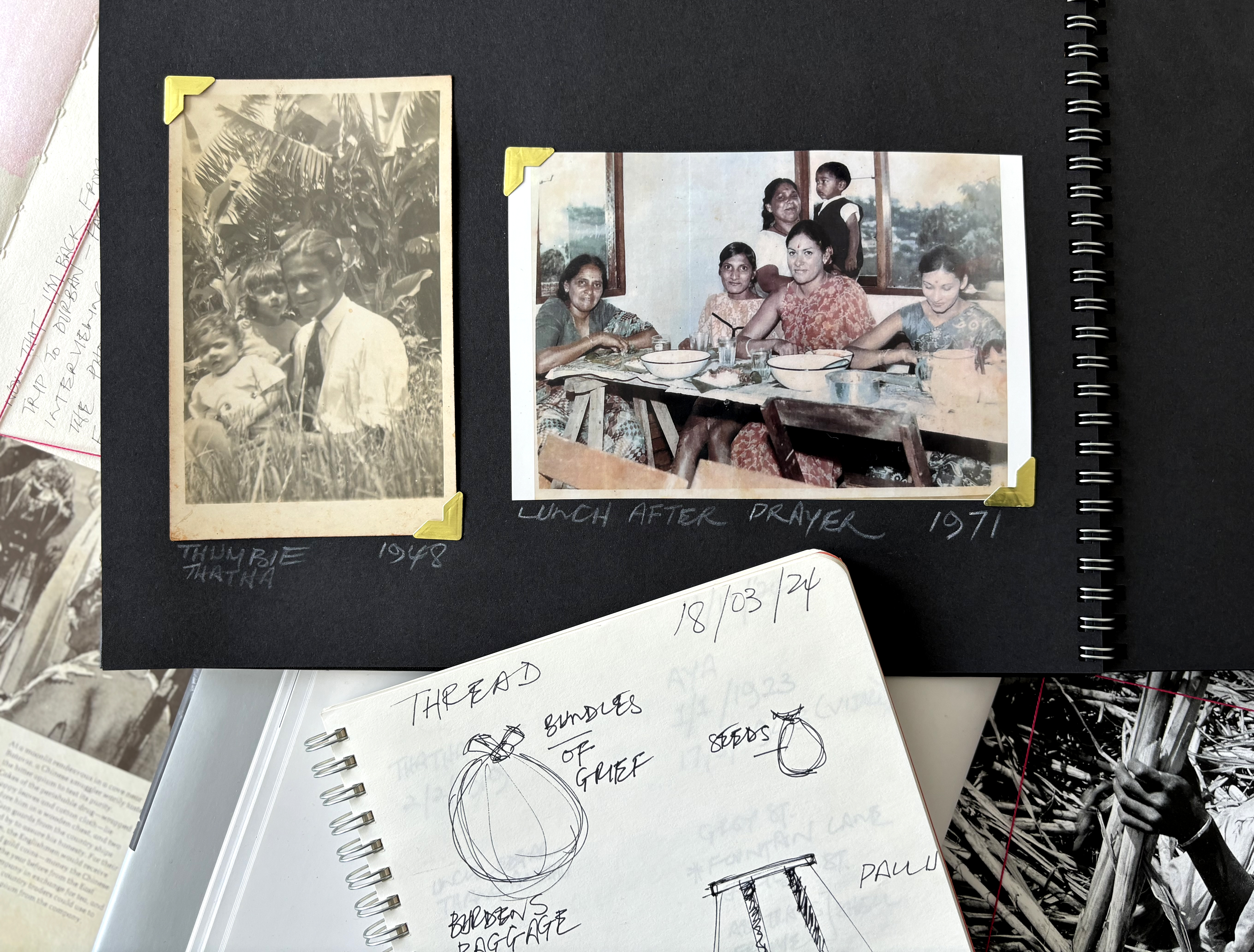

Research process. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

Research process. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

DM: Your work feels like a deeply intimate act of remembrance. What was the most emotional part of creating this project?

KN: When I started my sabbatical, I embarked on a journey of understanding the wider context of how my ancestors got to these shores. I knew that I am a descendant of Indian Indenture, a fourth- or fifth-generation South African of Indian ethnicity, but I had so much to learn about the British empire’s post-slavery solution to cheap labour in global colonies from 1834 to 1920.

More than 1.6 million Indians crossed the oceans to serve out contracts in more than 21 colonies, South Africa being one of them.

I made a realisation that my ancestors had endured invasions, colonisation, famines, dehumanising treatment and apartheid.

The struggles of the South African Indian through my research in Durban’s museums, bookshops and archives led me to ask my living relatives about their stories.

I trolled through photo albums and newspaper cuttings that some had kept, and through piecing together these threads I discovered parts of myself, I recognised myself and started to understand that we are not just blood and bones. We carry within us cellular memory, trauma triggers, inherited genius and personality traits are not just ours but that of the collective too.

A quick pencil and watercolour sketch I did during my research process while paging through a book. I wondered who he was and what may have become of him. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

A quick pencil and watercolour sketch I did during my research process while paging through a book. I wondered who he was and what may have become of him. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

A close-up of my great-grandmother. Looking at her clothes, I assume she was a widow when the photograph was taken, as she is wearing all white. I wanted to add some glamour to her outfit, so I added a lace and sequined skirt. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

A close-up of my great-grandmother. Looking at her clothes, I assume she was a widow when the photograph was taken, as she is wearing all white. I wanted to add some glamour to her outfit, so I added a lace and sequined skirt. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

DM: Ancestry can be both a source of strength and weight. Did working on this project shift the way you see your own place in your family’s lineage?

KN: Absolutely. My internal narrative changed so many times through this process over time. The “Man̄ci Biḍḍa” (good child) piece in particular carries both the strength and weight of what has defined me and my life in ways unknown until I marked on that piece. It was a term of endearment my maternal grandmother used in reference to me. The burden of being good in every decision, action and thought. This was not just an acknowledgment of my inherent goodness but a socialising of my future behaviour. A good child listens and does not defy the social structure of the family and community.

DM: If your ancestors could see this project, what do you hope they would feel or say?

KN: I hope they would feel seen, their stories told, even if only in fragments from fading memories and dusty photographs embellished by imagination and creative licence.

I hope they feel that somehow for future generations I’ve attempted to bring them back, make their existence material. They were once people with dreams, desires, challenges, disappointments and heartbreak, but their descendants also loved and respected them. I exist because of them and I am grateful for having been raised by them.

From Left: Vasun (aunt), Vijarl (aunt), Sushilla (mother) Naidoo, Radha Katharoyan (aunt) and Peggie (maternal cousin). 1982 (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

From Left: Vasun (aunt), Vijarl (aunt), Sushilla (mother) Naidoo, Radha Katharoyan (aunt) and Peggie (maternal cousin). 1982 (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

A close-up of the piece, Man̄ci Biḍḍa, showing the beading, embroidery and hand-painted words on a cotton dhoti with my maternal grandmother’s face printed onto the fabric. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

A close-up of the piece, Man̄ci Biḍḍa, showing the beading, embroidery and hand-painted words on a cotton dhoti with my maternal grandmother’s face printed onto the fabric. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

‘Man̄ci biḍḍa’ was a term of endearment my maternal grandmother used. A Telugu phrase meaning ‘good child’. Did I learn this at my aya’s knee, on her hip or while she combed my waist-length hair? Was it a description or a suggestion? Handpainted, beaded and embroidered onto a cotton ‘dhothi’ in Telugu script. The bottom sari was hand-embroidered by my grandmother about five decades ago, making the installation a collaborative one from beyond. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

‘Man̄ci biḍḍa’ was a term of endearment my maternal grandmother used. A Telugu phrase meaning ‘good child’. Did I learn this at my aya’s knee, on her hip or while she combed my waist-length hair? Was it a description or a suggestion? Handpainted, beaded and embroidered onto a cotton ‘dhothi’ in Telugu script. The bottom sari was hand-embroidered by my grandmother about five decades ago, making the installation a collaborative one from beyond. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

An image transfer of my maternal grandfather (top), his father’s shipslist. Bottom right: My maternal great-grandparents. Bottom left: My grandfather and his band. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

An image transfer of my maternal grandfather (top), his father’s shipslist. Bottom right: My maternal great-grandparents. Bottom left: My grandfather and his band. (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

DM: Which living person do you most admire?

KN: In my family, I’d say my aunts (my mother’s sisters) who shaped a major part of my early life – each one of them has given me gifts. My oldest aunt taught me about being a leader, the second one about being philosophical and kind; my youngest aunt, who I’m still quite close to, that having an open mind, a joyful attitude and listening to great music can keep you forever young.

DM: What is a trait you inherited from your ancestors that you are most proud of?

KN: A stubborn determination to do the right thing when all around me there may be dissenting voices. Sometimes that defiance is silence, other times it roars, sometimes it’s coming forward to lead with grace and integrity.

DM: If you could have a conversation with any historical figure from your ancestry, who would it be and what would you ask them?

KN: I think I would like to sit in a circle on the earth and speak with many of them. I’d love to hear their stories, their moments of weakness, of love and loss, their fears and their deepest secrets. Did they pray for their children and their children’s children? Am I okay and was all that raising from generation to generation bearing fruit? DM

This interview has been edited for clarity and publication.

An image transfer of my maternal grandfather top, his father's shipslist document, bottom right, my maternal great-grandparents. Bottom left: my grandfather and his band members. (Photograph: Courtesy of the artist)

An image transfer of my maternal grandfather top, his father's shipslist document, bottom right, my maternal great-grandparents. Bottom left: my grandfather and his band members. (Photograph: Courtesy of the artist)