Faranaaz Veriava is Head of Education at SECTION27. She previously worked at Idasa and headed the Western Cape office of the South African Human Rights Commission. Veriava was a founder of the Education Law Project at the Centre for Applied Legal Studies at Wits University and also worked as an advocate of the Johannesburg Bar.

On 16 June 1976, 20,000 pupils walked out of their schools in Soweto protesting against the imposition of Afrikaans as the language of instruction in African schools and demanding an equal education. Police responded with teargas and live bullets, leading to the massacre of hundreds of pupils. The protests that began on that day would be the renewed catalyst in the struggle against racial inequality until democracy was won.

Today, so many years later, despite the desegregation of schools, educational inequality, with racial and class bias, persists. Poor, primarily black learners continue to attend under-resourced schools to attain a substandard education. The primary focus for education rights advocacy in public interest organisations such as SECTION27 has therefore been about ensuring equal educational quality for learners attending these schools. This struggle is far from won.

There is however another education struggle that our youth are demanding we pay better attention to. This is the ongoing struggle of black learners attending elite and middle-class private schools and former white public schools. Because public interest organisations cannot always direct scarce resources to addressing the transformation issues at these schools, it is incumbent on parents and educators to do this more proactively.

Black learners attending elite and middle-class private schools and former white public schools experience racism, other forms of discrimination and alienation in myriad and often subtle guises. To survive at these schools, learners must assimilate to archaic cultural norms or risk having their identities and conduct questioned, if not pathologised, in ways that other learners do not experience.

As parents, we recognise this injustice and complain about it amongst each other, but we nevertheless coax our children to conform and assimilate while simultaneously preaching independent thought and pushing for academic excellence. As a parent, I too am guilty of this. This is because we fear the alternative — exile to a substandard public education system in an increasingly competitive and saturated job market. At another, perhaps unconscious level, we feel we must be grateful that our children attend these schools with their sprawling fields and impressive structures that we once could only admire from afar.

In 2015, the Gauteng Department of Education investigated a Curro Holdings School that was reported for racially suspect practices including segregating classrooms by race, hiring all-white teaching staff, and not including African languages as part of the school’s curriculum.

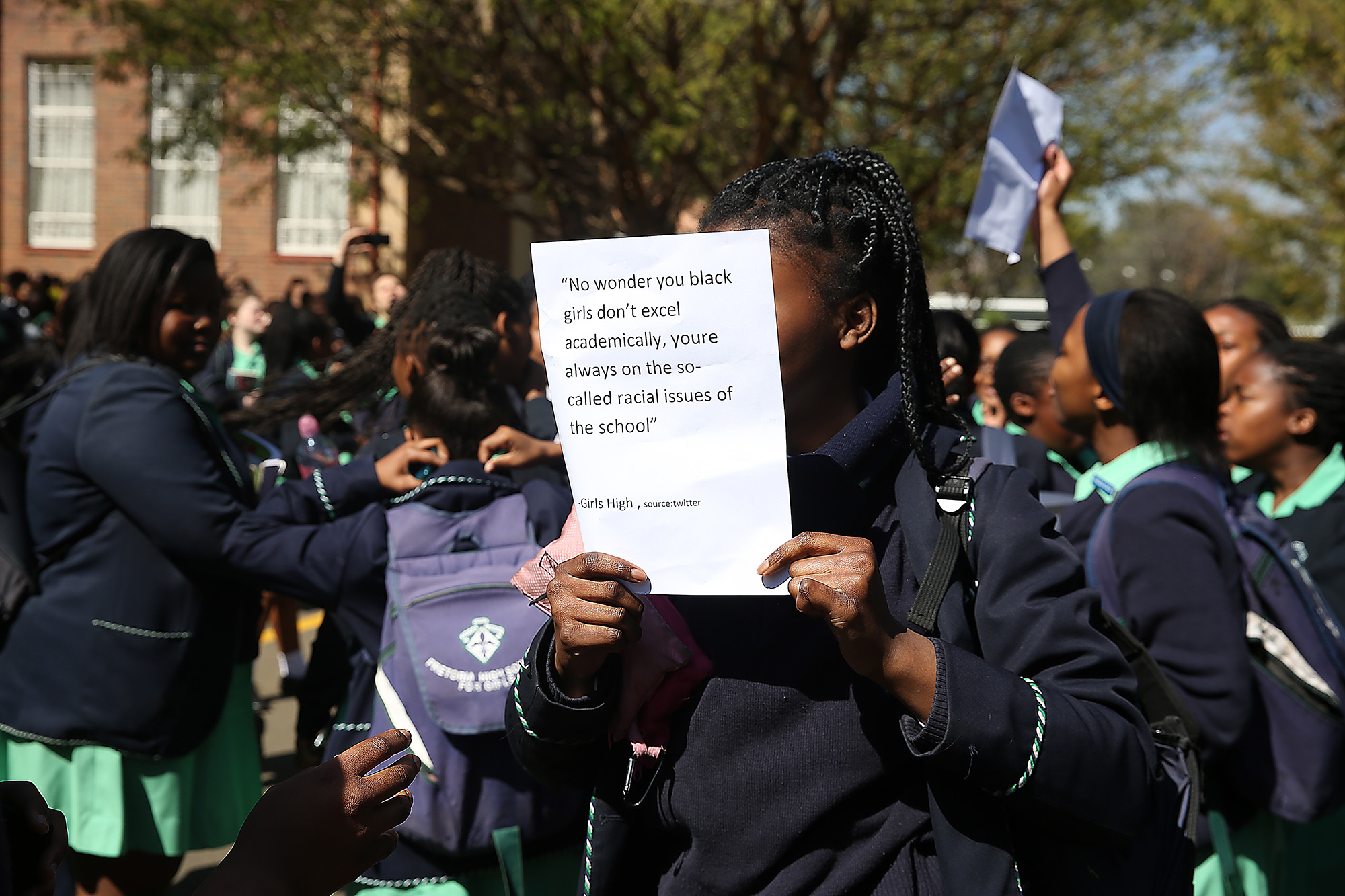

In August 2016, black learners at Pretoria High School for Girls received nationwide attention for protesting against institutional racism at the school. Their main complaint was in respect of the implementation by the school of its Code of Conduct, in particular its policy on hairstyles. Shortly after this, SECTION27 was approached by a group of dynamic young womxn to address a similar complaint at another school. SECTION27 successfully mediated the conflict through a change in the Code of Conduct without much fanfare.

In 2017, St John’s College came under fire for its failure to properly discipline an educator for racist remarks he made towards black, Indian and Greek learners. SECTION27 was approached for advice from a group of parents but chose to remain out of the fray because the parents were well resourced to advocate for themselves.

Last month, Cornwall Hill College in Pretoria publicly apologised to learners and parents for the delay in transforming the school. This apology followed eloquent protests from the learners and an equally impressive display of solidarity from parents including the Governor of the South African Reserve Bank, Lesetja Kganyago. The pupils’ memorandum of concerns was lengthy, documenting the daily experiences of learners subjected to microaggressions with comments about their appearance and hair. It raised concerns about the lack of diversity at all levels of the school including the lack of representation on the board of directors. It also noted the preferential treatment of some sports like rugby over others such as soccer.

These are the most public cases but there are many more instances. There are also the statements and acts of unconscious bias that shame our children and which make them feel “less than”, which they struggle to name or understand. The kinds of statements that tell a child he carries himself, “as if he belongs in a public school” (as if that is something to be ashamed of) or the disparities in punitive sanctions that, on close scrutiny, expose a racial bias. An ongoing complaint from learners challenging transformation in schools is that black learners tend to be punished more severely than their white counterparts. It is interesting that research into corporal punishment practices prior to it being banned reveals that while corporal punishment was used in boys’ schools — both black and white — white girls’ schools were not exposed to corporal punishment, but black girls’ schools were.

Certain private schools, in their own constitutions, declare their commitment to the South African Constitution, but such declarations do not always translate into practice. The Constitution with its vision of equality, non-racialism and non-discrimination, together with an ever-evolving progressive and transformative education jurisprudence, should be the lodestar for transformation charters that many schools are now developing.

In addition to race, private schools and indeed all schools, are prohibited from unfairly discriminating against learners, on a number of other grounds, including gender, sex, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth.

Our developing jurisprudence is addressing discrimination in its many forms as its manifests in an education context. This includes learners demanding accommodation for their religious and cultural practices in schools codes of conduct; learners with disabilities demanding accommodation and equal provisioning; and LGBTQ learners demanding accommodation in respect of uniform requirements.

A transformative education jurisprudence has also addressed authoritarian forms of discipline, requiring schools to move away from corporal punishment towards having respect for the dignity and freedom of pupils.

Most recently, our education jurisprudence tackled head-on the tendency of private schools to contract out of their constitutional obligations.

The high court case Mhlongo v John Wesley School and the Constitutional Case of AB v Pridwin Preparatory School shared the commonality that the private schools in each of these cases attempted to rely on a termination clause in the contracts that allowed private schools to expel learners from the school without due process. The latter judgment notes that: “[I]ndependent schools cannot be enclaves of power immune from constitutional obligations”.

Clear principles have been established in these cases that must be seeped into the institutional fabric of private school practices. These are the best interests of the child principle in terms of section 28(2) and the right to basic education in section 29 of the Constitution and, finally but importantly, the principle that private schools cannot maintain standards inferior to that of comparable public schools. The consequence of these cases and principles that derive from these cases is that learners cannot be suspended or expelled without being afforded the opportunity to be heard prior to a suspension or expulsion. Nor can private schools impose practices that would be clearly unlawful at public schools. This includes the meting out of corporal punishment or suspensions that are longer than that legally permissible at public schools.

In short, schools must go beyond simply stating their commitment to the Constitution. Schools would do well to review their codes of conduct and align their transformation codes in accordance with our education jurisprudence.

We are finally beginning to see educators who resemble wider society trickle into leadership positions at these schools. Black professional parents are also being wooed onto the governing boards of these schools so as to make the governance at these schools more diverse in their governing practices and to ensure transformation. Educators and parents must meet the challenge of transformation at their schools rather than be absorbed into the old norms and practices.

James Baldwin has said, “A child cannot be taught by anyone who despises him [or her].” So, when we witness our children struggle with alienation or when they are brave and push for change, let us stand with them. After all, they are becoming who we want them to be, even when we are afraid for them. DM/MC

Faranaaz Veriava is the head of the Education Rights programme at SECTION27.

South Africa

Time to address the struggles of black learners in private and former white public schools