Tony Heard’s loathing for injustice of any kind combined with unshakeable idealism was based on the belief that South Africa would overcome its post-apartheid challenges and that a nonracial democracy based on fair play would prevail in the long run.

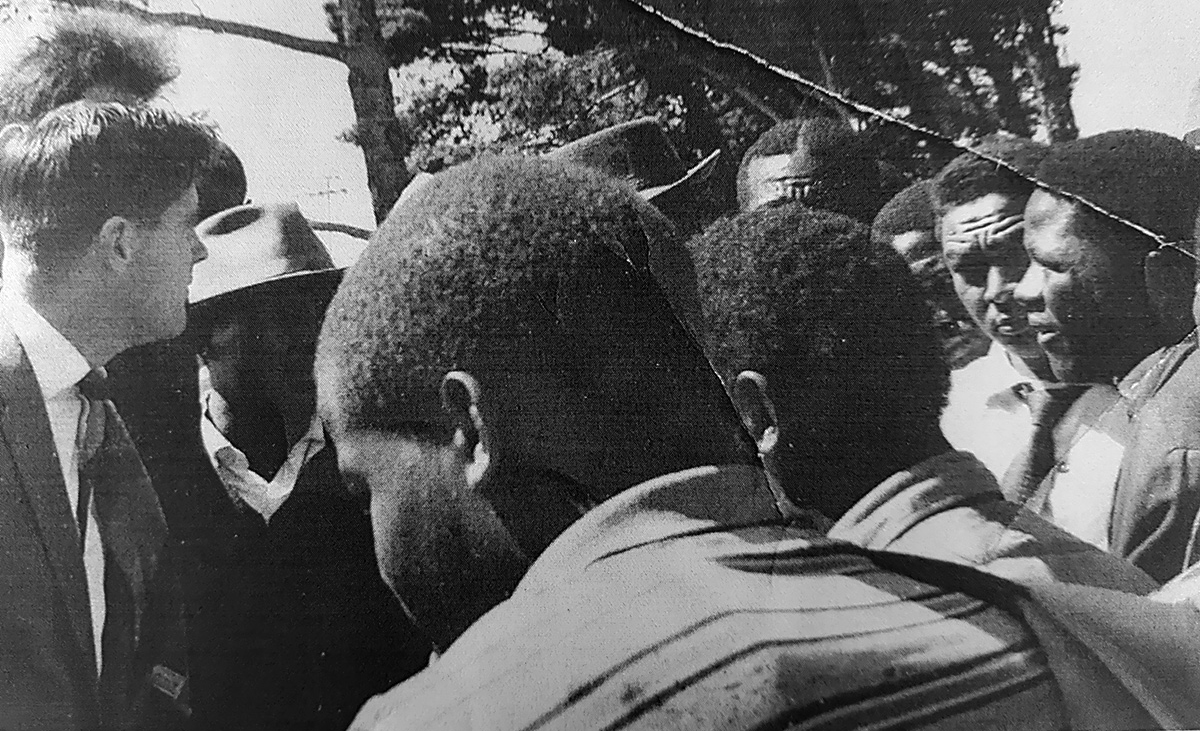

One of the two key drivers in Heard’s life was living through the horror of the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 and witnessing and then reporting on the historic protest march nine days later from Langa township to police headquarters in Cape Town led by Philip Kgosana, a UCT student and regional leader of the Pan Africanist Congress

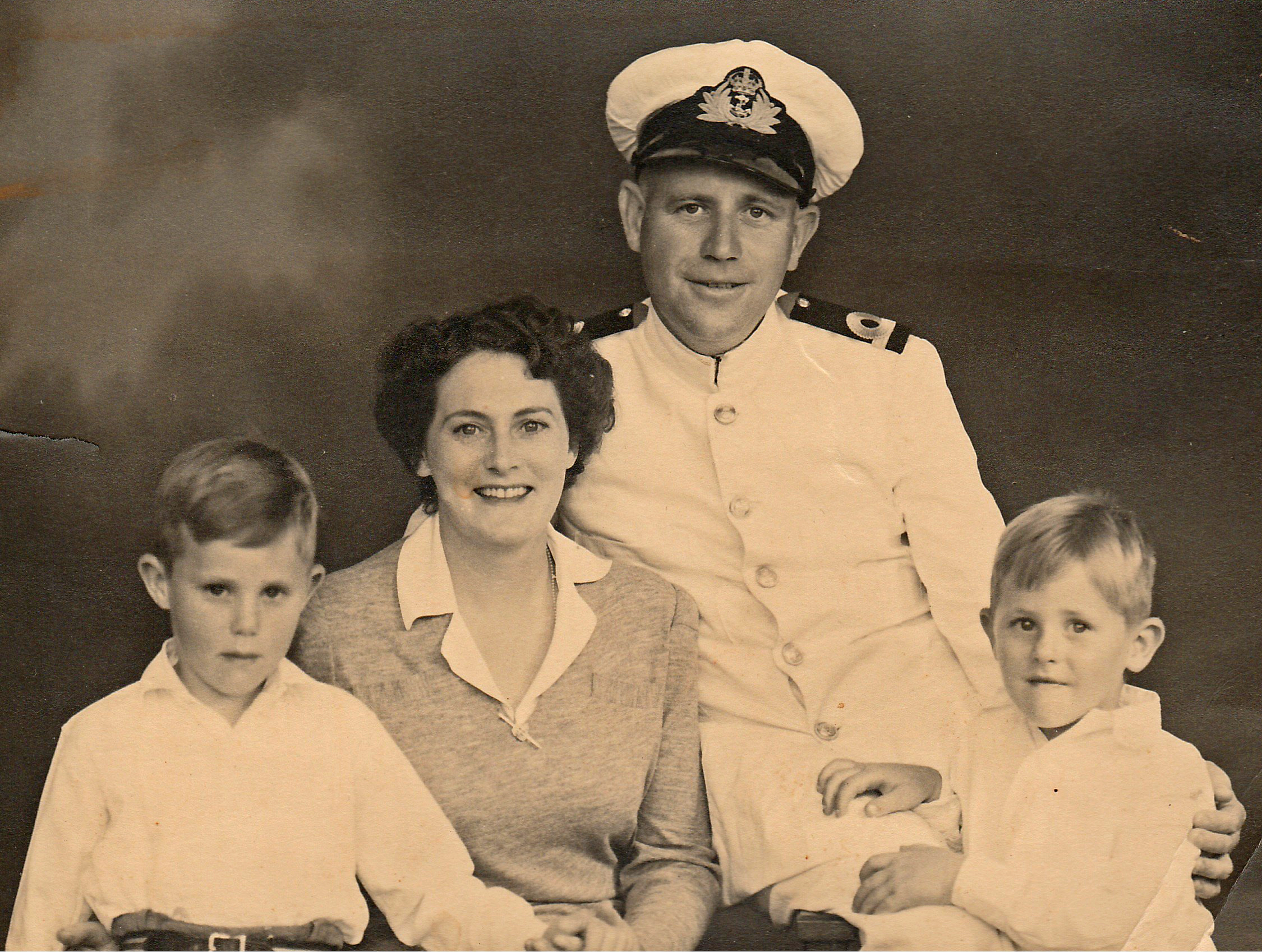

The second was Heard’s lifelong quest to resolve the mystery of his father, George’s disappearance in Cape Town while he was on active service against Nazi sympathisers during the closing days of World War 2. Heard was seven at the time of his father's disappearance.

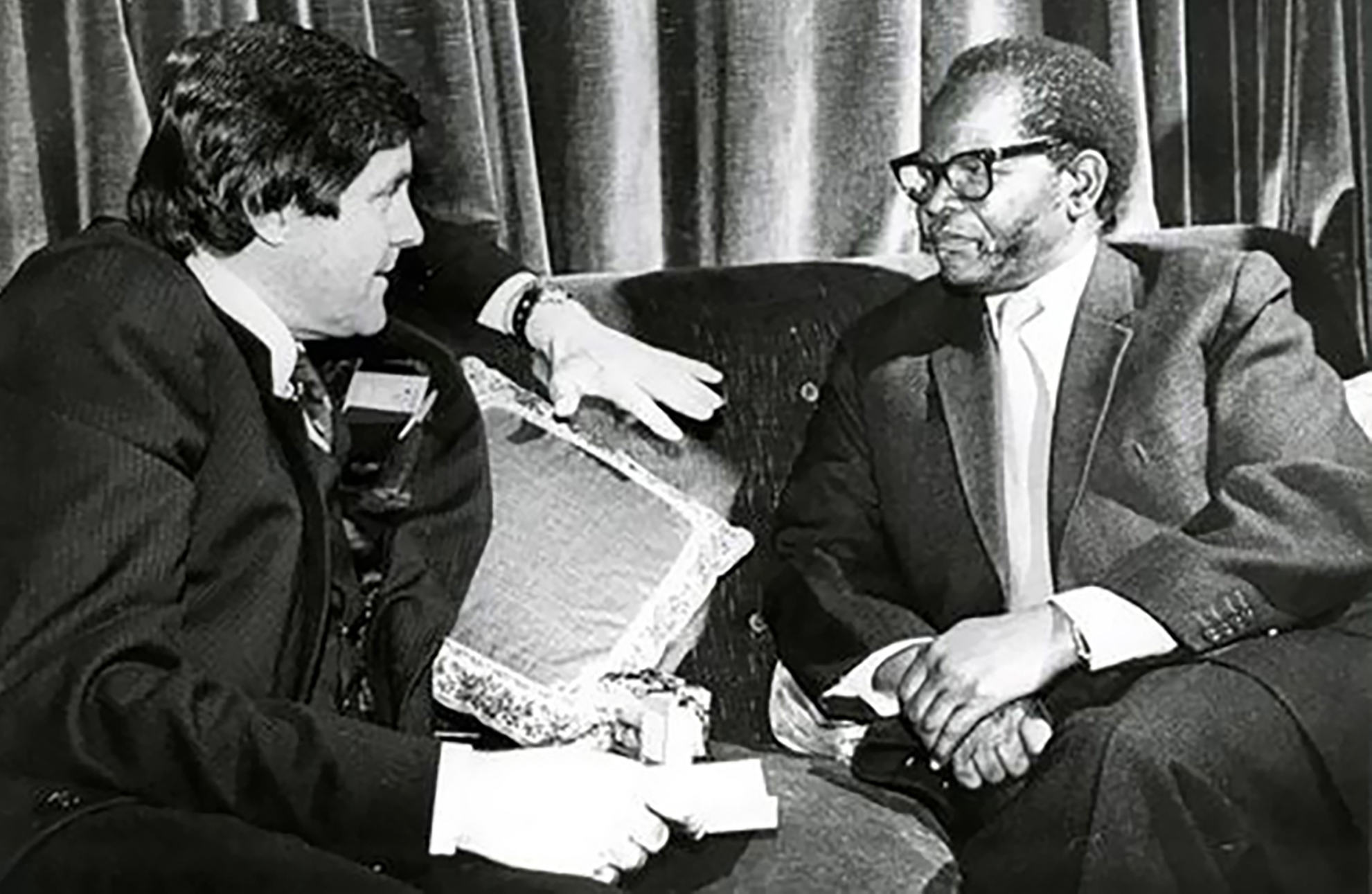

But the defining moment in Heard’s professional life was his decision to travel to London in October 1985 to interview Oliver Tambo, the outlawed leader-in-exile of the banned African National Congress in defiance of the banning laws in South Africa.

I had been writing a column from London as bureau chief for the Morning Newspaper Group.

On several occasions I pointed out to readers in South Africa that I was prevented by South African security laws from quoting what the leaders of the liberation movements were saying in the UK at a time when domestic resistance and international sanctions against South Africa were escalating rapidly.

Heard, who was editor of the Cape Times, was the only editor in the group who consistently published the column while others found it too overtly political.

I mentioned to Heard on one occasion that I was planning to set up an interview with Tambo and would leave it to editors to decide whether to publish.

One day in October 1985 I received a cryptic call from him to say that he was coming to London having taken leave from the newspaper.

We travelled together to the Tambo home in Muswell Hill.

Heard conducted the interview using a small tape recorder; it lasted more than an hour. Tambo answered the questions in soft and measured tones.

After the interview Heard bade me farewell and headed back to Cape Town without letting on what his plans were.

Two days later the 2,500-word interview spread across a whole page was published in the Cape Times on 4 November 1985 under the headline, A Conversation with Oliver Tambo of the ANC.

There was a front page cross-reference: Tambo Urges: Create Climate for Talks.

It was a premeditated act, which took courage born of a strong and independent spirit.

It was the first time in more than 25 years since the banning of the ANC that South Africans were able to read first-hand the reasoned views of a leader stereotyped in the South African media as a blood-thirsty terrorist.

Heard was arrested and released on bail after being charged with contravening the Internal Security Act for quoting a banned person.

Time passed and the case fizzled out with the newspaper company having to pay a nominal fine.

Heard won several press freedom awards including the Golden Pen Award of Freedom from the World Association of Newspapers.

He was dismissed two years later when he refused to accept a financial offer from the media owners to resign.

He felt betrayed by his employers, and the dismissal left a wound that never healed.

It fuelled what was already a strong professional relationship between us and developed into a close friendship spanning four decades.

Our careers had followed similar paths and we were always there for each other, evidenced by the hundreds of thousands of words exchanged in messages and calls over 40 years.

Seminal moment

Tony Heard, pictured far right, with his mother, Vida, father, George, and brother, Raymond. Naval officer Lieutenant George Heard disappeared without a trace from Cape Town in 1945. (Photo: Supplied)

Tony Heard, pictured far right, with his mother, Vida, father, George, and brother, Raymond. Naval officer Lieutenant George Heard disappeared without a trace from Cape Town in 1945. (Photo: Supplied)

On 30 March 1960, Heard had covered the historic anti-pass Langa march led by Philip Kgosana, nine days after mass police shootings at Sharpeville, and Langa had brought the wrath of the world down on prime minister and architect of apartheid Hendrik Verwoerd.

It was a seminal moment in his career and set the course for his future trajectory as editor and later government adviser.

He had learnt the meaning of courage and glimpsed that racial reconciliation was possible by witnessing how two men – Kgosana, who led a peaceful march of 30,000 protesters, and Colonel Ignatius (Terry) Terblanche, who had been given orders to open fire – could reach agreement swiftly to avoid a bloodbath at Caledon Square police station.

“Few knew then that Terblanche had fallen to his knees to pray in the police station just before going out unarmed with a small party of colleagues to parley with Kgosana,” Heard wrote 57 years later in an article in the Daily Maverick marking Kgosana’s death and revisiting the historic significance of that moment.

Tony Heard at the Langa anti-pass march in 1960. (Photo: Supplied)

Tony Heard at the Langa anti-pass march in 1960. (Photo: Supplied)

“Terblanche resolved rather to defy ministerial orders given him over the phone to ‘just shoot’. He risked his career for peace,” Heard recalled.

He had heard the negotiation between the two men first-hand. Kgosana would pull back the crowd on the grounds that he would be promised an interview with the justice minister.

The minister did not honour the pledge to meet Kgosana, despite the student leader leading the crowd peacefully back to Langa.

Six decades later Heard lobbied successfully for the De Waal Drive motorway – which the crowd had used – to be renamed Philip Kgosana Drive.

Heard lobbied until his death for Terblanche to be publicly honoured for his act of courage.

Heard was born in Johannesburg on 20 November 1937 to George, an anti-fascist activist who disappeared without trace in August 1945, and Vida, a journalist.

He was educated at Treverton College in KwaZulu-Natal and Durban Boys High, matriculating in 1954. He graduated from the University of Cape Town with a BA Honours degree in philosophy.

He became a parliamentary reporter in 1958 and later political correspondent.

Heard joined the Financial Mail as Cape editor in 1964, went to London in 1966 as senior correspondent in the SA Morning Newspapers Group office, and returned to South Africa in 1967 to take up the position of leader-page editor of the Cape Times.

He was appointed editor of the Cape Times in 1971. He served until his dismissal in 1987.

Thereafter he worked as an internationally syndicated freelance columnist, with contributions to the Los Angeles Times among other newspapers.

Surfer, beach bum and devoted family man

Tony Heard with two of his daughters, Vicki (back) and Janet. (Photo: Supplied)

Tony Heard with two of his daughters, Vicki (back) and Janet. (Photo: Supplied)

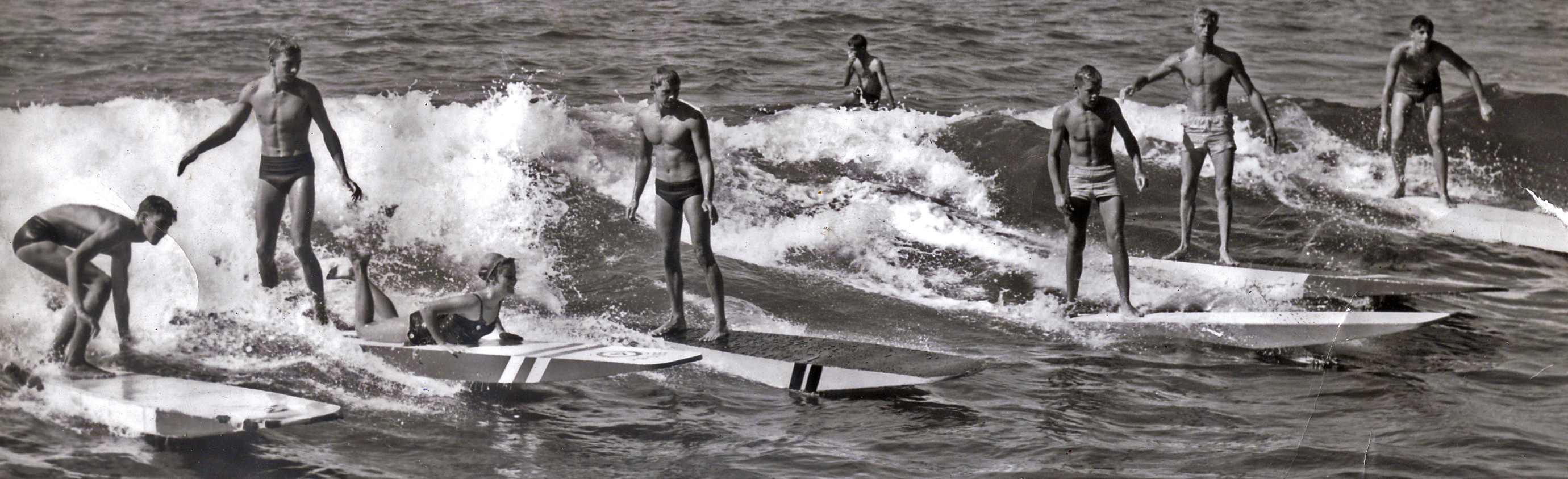

Tony Heard, far right, up and riding on the same wave with some of South Africa’s first surfers in the early 1950s at South Beach in Durban. (Photo: Supplied)

Tony Heard, far right, up and riding on the same wave with some of South Africa’s first surfers in the early 1950s at South Beach in Durban. (Photo: Supplied)

In 2000, he was appointed as special adviser to the Minister in the Presidency of Thabo Mbeki, quitting at the end of January 2010, months after Jacob Zuma became president (in 2009).

Tony had a lifelong relationship with the sea as surfer, swimmer and beach bum with his elder brother Ray in their youth.

He loved his family dearly. He is survived by his beloved life partner Jane, his four children Vicki and Janet from his first marriage to Val (nee Hermanson)

and Pasqua and Dylan from his second marriage to the late Mary Ann Barker, and by his grandchildren Jessica, Tyler and Ella, and brother Raymond.

Heard is the author of two published books: The Cape of Storms: A personal history of the crisis in South Africa (Ravan Press, 1991) and 8000 Days: Mandela, Mbeki and Beyond: The inside story of an editor in the corridors of power (co-published with Missing Ink, 2020). His daughter Janet has been entrusted with the manuscript of what will be his third book, about his quest to find the truth about his father’s disappearance. DM

Tony Heard, far right, up and riding on the same wave with some of South Africa’s first surfers in the early 1950s at South Beach in Durban. (Photo: Supplied)

Tony Heard, far right, up and riding on the same wave with some of South Africa’s first surfers in the early 1950s at South Beach in Durban. (Photo: Supplied)