The tar road to our first stop, Graafwater, is peachy. Then, we take the dirt track to Doring Bay and pass an ominous sign warning us to avoid this stretch when it’s wet.

Sliding around in the deep, sticky muck of the Sandveld might be someone’s idea of a good time, but it’s not for us. After some dramatic near-collisions with cows and farm gates, I remember that our vehicle comes with a diff-lock. Life eases up slightly after that.

An old bakkie approaches, yawing through the mud furrows. I jump out and become a human stop-sign. The guy hits a huge puddle and begins to fishtail in our direction, thankfully coming to a halt one metre before smashing into us. We ask him where the famous explorers’ cave could be.

The genial farmer says we passed the Heerenlogement about two clicks back.

“The sign fell down. It’s just lying there,” he says.

The Heerenlogement Cave sign – easy to miss. (Photo: Julienne du Toit)

The Heerenlogement Cave sign – easy to miss. (Photo: Julienne du Toit)

Open gate entrance to the Heerenlogement Cave. (Image: Chris Marais)

Open gate entrance to the Heerenlogement Cave. (Image: Chris Marais)

The rocky outcrop above the Heerenlogement Cave – the Holiday Inn of its time. (Image: Chris Marais)

The rocky outcrop above the Heerenlogement Cave – the Holiday Inn of its time. (Image: Chris Marais)

The Gentleman’s Lodging

Once you know where to look, it’s easy. The Heerenlogement (Gentleman’s Lodging) is a rocky shelter that most old-time explorers, botanists, missionaries, prospectors, painters and fossil-hunters used as an overnight stop between Cape Town and the Orange River. There was fountain water available, and grazing for their oxen just below.

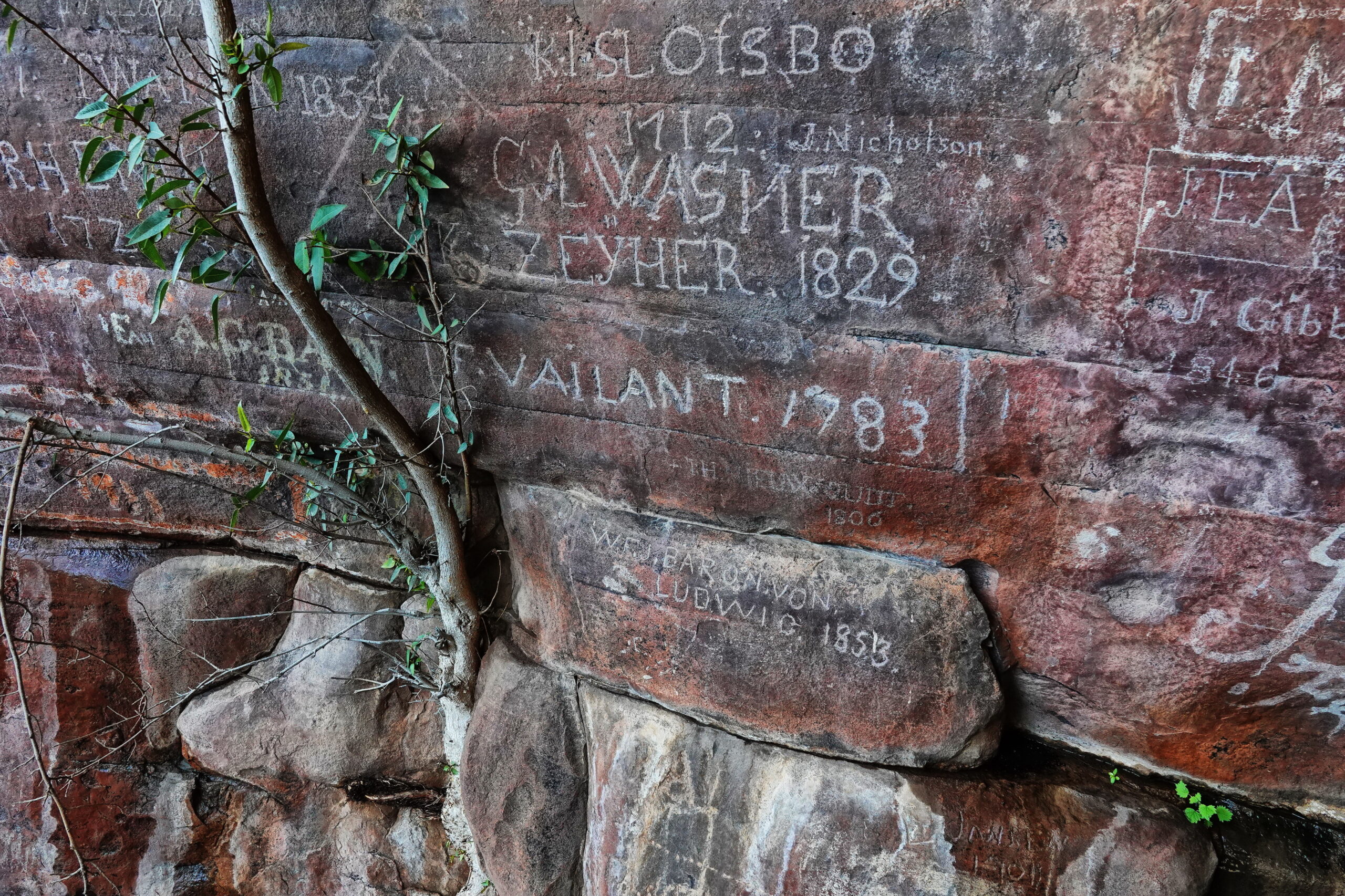

Many of these hardy chaps etched their names and arrival dates on the rock face of the Heerenlogement, so it resembles a venerable guest book with a twist. Travellers rested here as far back as 300 years ago. On this cluttered wall of historic graffiti, you see the initials of James Alexander (of Alexander Bay fame), that of the all-round creative Andrew Geddes Bain, Captain KJ Slotsbo who was on military recce in the north, and his companion Caspar Hemery who carved a little trumpeting elephant next to his name back in 1712.

On the right-hand side of the fig root next to Bain, stands the name of the colourful French adventurer and bird nut Francois le Vaillant. But he didn’t take to the Heerenlogement.

“It filled me with melancholy and discouragement,” he records.

Francois was presumably so depressed by the place that he managed to misspell his name when he scratched it into the wall before departing, possibly in a bit of a huff. Maybe the tricksy Sandveld roads had angered him as well.

The Heerenlogement would have been the Holiday Inn of the Namaqua Copper Highway back in the 17th century, when the colonial Dutch down in Cape Town went mad for the metal and sent waves of explorers and prospectors north in search of the fabled Koperberg.

Early Colonial graffiti in the Heerenlogement Cave, Sandveld, Western Cape. (Image: Julienne du Toit)

Early Colonial graffiti in the Heerenlogement Cave, Sandveld, Western Cape. (Image: Julienne du Toit)

Even the great roadbuilder and explorer Andrew Geddes Bain left his mark at the Heerenlogement. (Image: Chris Marais)

Even the great roadbuilder and explorer Andrew Geddes Bain left his mark at the Heerenlogement. (Image: Chris Marais)

The French explorer and naturalist Francois le Vaillant signed his name (slightly misspelt) after a brief sojourn here. (Image: Chris Marais)

The French explorer and naturalist Francois le Vaillant signed his name (slightly misspelt) after a brief sojourn here. (Image: Chris Marais)

The Fryer family, on their way to a new life in the Calvinia area. (Image: Chris Marais)

The Fryer family, on their way to a new life in the Calvinia area. (Image: Chris Marais)

Copper culture

Known as the “Peacock of Metals”, copper has always been favoured, from ancient days to present times. It’s easily found in its metallic state, it’s malleable, decorative and downright handy. And it plays nicely with a number of other metals.

The Serbs smelted copper 7,000 years ago, the Romans were expert coppersmiths, and the Aztecs traded in copper axes. The Hittites, Cypriots, Babylonians and Egyptians used it as money, while Mesopotamian metalsmiths made practical objects like wine mugs, harpoons and razors, using copper with a dash of tin to produce bronze.

King Solomon understood the value of copper three millennia ago, Greek sculptors developed the amazing lost wax casting technique in the 6th century and made copper pieces that stand to this day, and now copper is essential for the production of components in various industries which include telecoms, renewable energy, household objects like doorknobs, railings and wrenches – more than 80% of all the copper ever mined is still in use somewhere in the world today.

So you can imagine the look of delight on governor Jan van Riebeeck’s face back in 1661 when explorer Pieter van Meerhof tells him:

“Their dress consists of all kinds of beautifully prepared skins, gorgeously ornamented with copper beads. Their locks they thread with copper beads, covering their heads all over. Around their necks they have chains, slung round them 15 or 16 times. Many have round copper plates suspended from these chains. On their arms they have chains of copper and iron beads which go round their bodies 30 or 40 times. Their legs are encased in plaited skins, ornamented with beads… Their only industry is working in copper and iron, from which they make very neat beads and chains.”

Van Meerhof is talking about the Namaqua people he’s encountered on his travels. Twenty years later, a group of Namaqua visit the Cape Town Castle, bearing copper in all kinds of shapes and sizes. Mention is made of a Koperberg – a Copper Mountain.

Van Riebeeck sends his man Olof Bergh up to look for all this copper and, when he comes back empty-handed, dispatches Sergeant Isaac Schrijver with a party of soldiers and miners. He returns with a modest amount of copper, enough to be fashioned into ingots and sent as display samples to the head honchos at the Dutch East India Company.

Simon van der Stel takes a massive caravan of wagons, a couple of artillery pieces and more than 60 assistants up north (talk about overpacking), finds the Koperberg in what is today known as the Springbok-Okiep area and returns with some enthusiasm and plenty of samples. However, the copper quality is deemed to be sub-par and the distances from the sites to the sea just too great. The Company does not see it as good business.

Copper-crazy

By the mid-19th century, however, Northern Namaqualand became the epicentre of one of the world’s most frenetic copper booms. The Dutch East India Company is but an entry in the history books, huge copper deposits have been found all over the area and the game is on.

Companies are formed, the bogus prospectus business is hotter than ever, hopes are up everywhere, from London to Cape Town, Cornish miners are arriving in droves and labour brokers are struggling to keep up with demand.

Coming up trumps is the Namaqua Mining Company (Concordia concession) and an outfit called Phillips & King, with mine sites in Springbokfontein, Spektakel, Okiep and Nababeep. What follows over the decades is a series of copper slumps and booms, with the copper villages shrinking and expanding accordingly. DM

This is a short chapter excerpt from Karoo Roads IV – In Faraway Places (360 pages, black and white photography, R350 including taxes and courier in South Africa) available from September 2024. Anyone interested in pre-ordering a first edition, author-signed copy should please contact Julie at julie@karoospace.co.za for more details.

The Karoo Quartet (Karoo Roads 1 – 4) consists of more than 60 Karoo stories and hundreds of black and white photographs. Priced at R960 (including taxes and courier in South Africa), this Heritage Collection can also be ordered from julie@karoospace.co.za

The Fryer family, on their way to a new life in the Calvinia area. (Image: Chris Marais)

The Fryer family, on their way to a new life in the Calvinia area. (Image: Chris Marais)