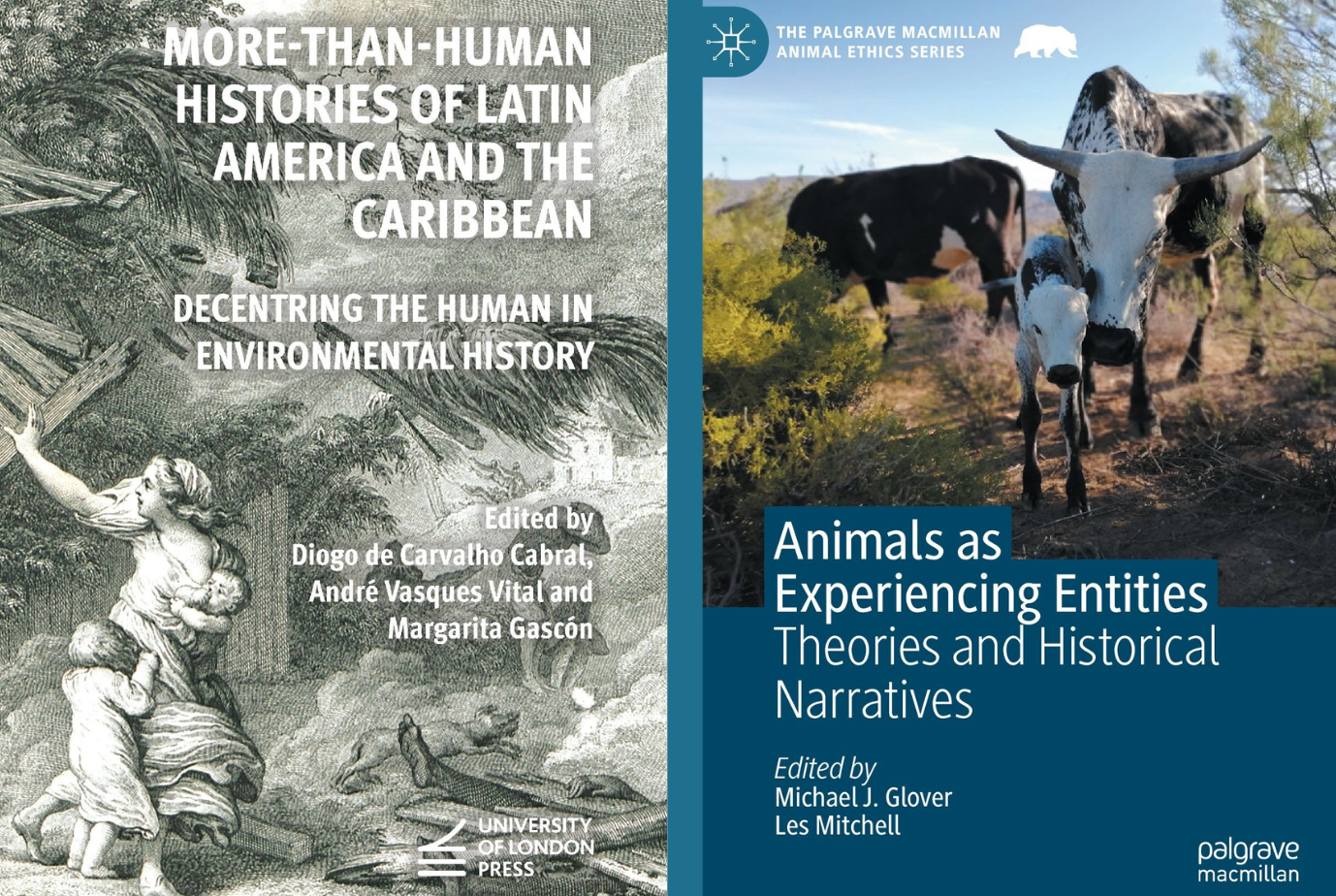

Animals as Experiencing Entities: Theories and Historical Narratives endeavours to move the needle from abstractly recognising animals as subjects to theorising about animals’ experiences and specifically exploring their historical experiences.

Animals – or “non-human animals” as they are largely viewed in this collection of essays edited by Michale J Glover and Les Mitchell – take centre stage in this volume as agents of historical change.

“Animals’ hidden and interior lives, intertwined with humans in myriad ways, comprise narratives which have been suppressed by dominant powers and ideologies at the time of the events and are often still marginalised today. We think decency demands that the animals’ stories be told, and justice requires that we tell them as honestly as possible,” the editors write.

But animals are not the only non-human actors on this expanding stage of environmental history.

More-than-Human Histories Latin America and the Caribbean, edited by Diogo de Carvalho Cabral, André Vasques Vital and Margarita Gascón, includes insects but also climate change, rivers and earthquakes to demonstrate how that region’s history has been forged by forces that were not always human.

Together, the two volumes offer a useful primer for this emerging approach to the study of history.

How earthquakes shook up the Chilean state

In the volume focused on Latin America and the Caribbean, the standout chapter for this reviewer is Magdalena Gil’s “Forjadores de la nación: rethinking the role of earthquakes in Chilean history”.

Gil is superb historian and gifted writer, and from the shifting fault lines that lie below the surface she masterfully charts how a menacing geology gave rise to the state in Chile, one of the most earthquake-prone countries on Earth.

“Most of the time, there is nothing safer than being ‘on the ground’, the earth being our natural domain as a species. We call people ‘grounded’ when we think they are stable, level-headed and reliable. An idea is ‘grounded in theory’ when it has solid theoretical foundations,” Gil notes.

“Yet, in seismic countries, the ground every now and then reminds us that earth is not the stable, inert background against which human action unfolds.”

Gil’s focus is “... on earthquakes’ role in pushing an agenda of state-building on to human actors that were not always in line with this project. By doing so, I don’t aim to give earthquakes human-like historical power, but to provide further evidence that human agency – however we define it –‘cannot be separated from the environments in which that agency emerges’.”

Gil further notes that Chilean commentators have long drawn attention to the country’s “telluric character”, and she unpacks how this has been baked into the historical DNA of the state.

“Earthquakes have forced institutions to develop new capacities and expand their authority, to the point that we cannot truly understand the Chilean state without considering its relationship with earthquakes.”

There is also a link here with secularisation. If earthquakes are “Acts of God”, then humans can’t do much about them. But if they are natural events, then humans can try to understand them to mitigate their impact.

“By 1906, there were very few issues that the Chilean state considered its own responsibility beyond internal security and trade. But earthquakes were quickly becoming a major public concern, precisely because they challenged the continuity of such activities,” Gil writes.

Public policy overlooked

This state of shaky affairs “... forced the state to care about several issues in public policy that were being overlooked, and pushed to develop new capacities in areas such as infrastructure planning and irreparable damage seismology, effectively moving the standard for acceptable state intervention for years to come.”

So earthquakes forced the Chilean state to assume roles that would not have been regarded as its domain if the ground had not moved with such regularity and ferocity.

One clear example on this front is building codes, which Gil observes can be regarded as “a rather extreme form of state power”.

The upshot was that in the wake of the 1939 quake, the building codes mostly withstood the tremors. Fewer than 20% of buildings constructed under the new codes experienced “irreparable damage”, a stark contrast with the 67% of those that made use of the traditional adobe design and material.

This is of more than passing interest because the role of the state – and Chile’s and more broadly Latin America’s seismic left/right divides – have produced more than their fair share of political earthquakes.

In the case of Chile, Gil concludes that “... we see a dialogical process in which the Chilean state has learned to adapt to the telluric forces that visit the territory. As García Marquéz claims, this relationship has helped achieve a certain ‘political maturity’.”

Other essays in this evocative collection probe issues such as human-insect relations in Brazil’s sugar industry, the role that rivers played in the flow of Rio de Janeiro’s 19th-century history, and the effects of climate in New Spain and Guatemala in the late 18th century.

Like any anthology, this one is uneven – Gil’s is the best in this reviewer's view–but they underscore new streams of thought that are carving out fresh insights into history and humanity’s diminished role on its banks.

The animals in our history – and their history

Turning to the other volume reviewed here, the focus is on “non-human animals”, but this reviewer remains comfortable with the term “animal” – a reflection of my own upbringing in a certain period of history and its cultural currents.

Perhaps I am being anthropocentric, but some adjectives are unnecessary. The audience of this book is human – no horse or chimpanzee is going to read or discuss it, so their feelings are not going to be hurt.

Having said that, the turn towards animals in history is useful, exciting and innovative. Another recent example that I have reviewed is Sandra Swart’s excellent and readable “The Lion’s Historian: Africa's Animal Past.”

Animals as Experiencing Entities complements the Latin American volume and Swart’s book in highlighting the directions that animal history is taking. Some of these turns are insightful, though others are problematic.

In the chapter “Critical Animal Historiography, Experiential Subjectivity and Animal Standpoint Theory”, Kai Horsthemke writes that “‘Critical animal historiography’ regards other-than-human animals as subjects of and as both agents and recipients in history, as individuals who impact and who are impacted by historical processes.

“Historiography, the writing of history, has characteristically posited the ahistoricity of animals. In contrast with humans, animals continue to be perceived as the embodiment of the ahistorical ‘other’. For example, ‘cattle’ have been referred to, albeit mistakenly, as the oldest and most important domestic animals. Limited to their role as ‘livestock’ and defined exclusively in terms of their instrumental value within human society, they have no history — and no identity.”

This all draws on a range of historical precedents, including the often Marxist-influenced “New Social History” of the 1960s that sought to widen the historical lens to capture the previously ignored experience of the working class, peasantry, women, children and people of colour.

Environmental history would be one of the branches that sprouted from this trunk, but this also had roots in the French Annales school of thought that examined long-term historical processes that were moulded by factors such as geography, climate and soil.

Historical vacuum

Historians and those in related fields do not work in a historical vacuum, and the essays in Animals as Experiencing Entities are very much a product of current concerns about animal welfare and rights.

This is understandable, but it can also at times undermine the approaches taken.

For example, in the introduction, the editors cite the pioneering animal historian Éric Baratay.

“He argues that the lives of animals need not be a black hole in history. He asserts that we ‘must also abandon the culturally constructed Western notion of animals as passive beings and see them instead as feeling, responding, adapting, and suffering’.”

This is frankly an astonishingly ahistorical assertion. The view that animals – or “non-human animals” if you prefer – feel, respond, adapt and suffer is very much a “culturally constructed Western notion”.

This viewpoint draws heavily on the Enlightenment and the West’s historical intellectual heritage. The great English historian Keith Thomas four decades ago in his ground-breaking book Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England, 1500-1800, charted the growing realisation in the 17th and 18th centuries that animals could feel pain, which gave rise to Europe’s first vegetarian movements.

The 19th century was also illuminated by Charles Darwin’s brilliant insights, which highlighted our kinship to other animals; the related discovery that species could go extinct and that human activities could be a cause; and our unmooring from the natural world, brought about by the twin forces of urbanisation and industrialisation, which in turn gave rise to a penchant for romanticising it.

On this front, in one of the essays Jonathan Saha unpacks the historiography of “great animal massacres”. I found this chapter very informative but it at times also fails to take note of this vital historical background.

For example, one section is devoted to “the great crow massacre of colonial Rangoon”. The British administration employed three gangs of Indian labourers to destroy nests and chicks – on the baseless grounds that crows spread disease – triggering the wrath of Buddhists and fuelling the flames of Burmese nationalism.

Saha says this avian massacre also highlighted the cultural divide between the British administration and the city’s Hindu and Buddhist communities, whose representatives on the municipal committee initially blocked the plan when it was hatched.

A ‘racially coded sign’

“That Asian religious sensibilities could be extended to crows was, for some white commentators, a racially coded sign of the colonised population’s overly sympathetic attitude to animals,” Saha writes.

But many members of the British community would have come from backgrounds that would have been “overly sympathetic” to animals as well.

One of the many things that Keith Thomas drew attention to was the fact that British animal anti-cruelty campaigns preceded those focused on children. The current animal rights and welfare movements have many noble attributes, and such thinking informs much of this collection. But they also have classist and racist roots which have put the welfare of animals above that of the people previously marginalised by history.

I saw an arresting example of this in June when I was in Zambia to report on the aftermath of a botched elephant translocation to Kasungu National Park in Malawi – spearheaded by the NGOs the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) and African Parks – which has transformed the landscape into a hellscape of fear and loathing for some of the world's poorest people.

The Western donors who funded this initiative clearly have a high regard for elephants and their welfare, but this has not been extended to the rural African poor who are being terrorised by the pachyderms.

Returning to the study of history, the addition of species and concepts such as animal agency to race, class and gender does indeed broaden our understanding of the past. But these trends can also reveal the racism and classism of a movement that considers itself to be part of the progressive left.

I would add that the competing trends in the wider conservation movement currently, which call for the sustainable use of wildlife, including hunting, also have pasts tainted by racism and colonialism. But regarding animals wild and domestic as having consumptive uses for humans is hardly a “Western cultural construct”. It is a global phenomenon found in most human cultures throughout history.

This critique aside, some of the essays in this volume have certainly broadened my own understanding of the past.

The chapter “Sensing Life: Intersections of Animal and Sensory Histories” by Andrew Flack and Sandra Swart is a nuanced examination of “... the significant potential of an animal-orientated sensory turn. We want to make the case that it is substantially through the senses — by thinking about what sensory experiences were and what they meant in the context of human-animal relations — that we can draw closer to the lived realities of past animals — and their people.”

The study of history is never static and our view of the past is often a reflection of the present, which in turn can offer a glimpse of the future. The rise of interest in the “non-human” actors in the great drama of history, be they horses or earthquakes, is part of what EH Carr described as “... an unending dialogue between the present and the past”.

This is exciting stuff that is opening new historical paths. And as is always the case with history, it can sometimes cast our own perspectives in an unflattering light. DM