The Reading List: Your career spans more than two decades, starting with Far Horizon and its focus on elephant poaching. How do you believe your storytelling has evolved over these years, especially in the way you address the themes of wildlife conservation and crime?

Tony Park: As a writer, I like to think that I’ve continued to learn over the past 20 years; I’ve been lucky enough to work with some of the best publishers and editors in the business at Pan Macmillan. In that time I’ve also grown from a tourist overawed by my early encounters with wildlife to someone who now lives most of the year in South Africa – I think that’s reflected in my storytelling as well. I think my characters these days better reflect the diversity, challenges and strengths of southern Africa; when it comes to crime and wildlife I’m also trying to get across the message that it’s not just elephants and rhinos that are under threat, and that crime comes in many forms.

TRL: What specifically drew you to focus on pangolin poaching in The Protector, and could you share some of the most impactful moments during your research that shaped the narrative of the novel?

Tony Park: One of the reasons pangolins have not attracted the same publicity as other endangered species is that they are small, secretive, and rarely seen by visitors to Africa on safari. Nonetheless, they are ruthlessly hunted and killed for their scales.

Although made of keratin – the same thing as human fingernails, there’s a belief that they cure various ills and improve lactation for new mothers. A species is being wiped out based on superstition.

I’ve wanted to write a novel about pangolins for several years but the world of pangolin conservation is, for security reasons, quite a closed one. I was lucky that Lauren Tink, a master’s student from Tshwane University, who read my books and was studying pangolins, came to one of my book talks and suggested I revisit the idea. She opened some doors for me, and introduced me to Professor Ray Jansen, South Africa’s pre-eminent pangolin expert and founder and past head of the African Pangolin Working Group. He was incredibly helpful with my research and I’m forever in Lauren’s debt for the introduction.

In 29 years of visiting national parks and reserves around southern and east Africa, I’d never seen a pangolin.

To be granted access to a rehabilitation facility near Phalaborwa was a privilege not afforded to tourists. Just to see these amazing little creatures going about their business, but under the watchful idea of tireless volunteers who spend hours and hours just walking with them, watching over them, was incredibly moving in a very simple way.

When a pangolin encounters danger its defence mechanism is to roll itself into a ball. Yet Professor Jansen and others I met involved in pangolin rescue and rehabilitation told me that pangolins seem to be able to tell the difference between “good” humans and “bad” ones. Pangolins that were dehydrated and malnourished in captivity have been known to “unroll” as soon as their rescuer handles them.

TRL: Considering that pangolins are less well known than other endangered species like rhinos and elephants, what challenges did you face in bringing their plight to the forefront of your readers’ minds?

Tony Park: I had friends from Australia come to visit me in South Africa recently, and one of their friends, who had read some of my books, asked me what my new book was about. When I said “pangolins”, he said: “What’s a pangolin?” That gave me a wake-up call.

It’s hard to describe an animal you’ve only seen once, but the best descriptions in the book come not from me, but from little anecdotes and observations related to me by the experts – academics Ray and Lauren, and a woman involved in pangolin rehabilitation.

TRL: Your novel includes scenes of undercover operations that mirror real efforts to combat poaching. I hear you even witnessed a live undercover bust of pangolin poachers. Could you share your experience, and how it influenced the storyline of The Protector?

Tony Park: I was on my way to the Umoya Khulula wildlife rehabilitation centre in Limpopo, to see a pangolin for the first time in my life, when my contact there told me she would be late because she was about to join a sting operation, to bust suspected pangolin poachers in the Lowveld town of Hoedspruit.

As I came into Hoedspruit I saw a crowd outside the Wimpy and when I pulled in I realised I was witnessing that operation unfolding.

Aside from the high drama of seeing several armed male and female plainclothes operatives revealing themselves, and alleged poachers being handcuffed and laid on the ground, there was immense curiosity from shoppers and passers-by who gathered to watch the aftermath of the operation.

Professor Jansen told me how he sometimes used these very public occasions to show off a rescued pangolin to the crowd, to educate them, and I worked this educative element, as well as the action, into the opening scene of The Protector.

Just as in my novel, the bust resulted in some members of the public becoming quite angry with the alleged poachers, whom they saw as robbing South Africa of its natural heritage.

TRL: How did your collaboration with pangolin expert Jansen and participation in wildlife conservation efforts inform your writing of The Protector?

Tony Park: I always tell aspiring writers that the best way to research is not to trawl the internet, but to look for real people – experts in their field – and to pick their brains. I could not have written this book without Ray or Lauren; if I had, it would not have been nearly as realistic.

It was the experts’ insights into the “character” of pangolins and some very moving moments they recounted to me that I think make the novel more believable.

Apart from the factual information about pangolins, Ray also spoke honestly of the highs and lows of being involved, literally, in the frontline of conservation. He has faced danger on numerous occasions and received death threats. He admitted that the grind and stress of undercover operations in a fight that seemingly has no end takes a heavy toll on those involved. I worked these personal reflections into my fictitious character, Professor Denise “Doc” Rado.

TRL: During your research, you also encountered the tragic assassination of an undercover agent. Did this and the similar real-life dangers faced by those protecting wildlife influence your writing?

Tony Park: It actually happened the other way around. After talking to Ray and Lauren in the early stages of writing I went away and finished the manuscript. Given that I write thrillers I wanted to raise the stakes when it came to danger and the threat to my fictitious characters – a couple of people lose their lives in the fictitious story.

When I sent Ray the draft manuscript for him to check I was shocked to learn that what I thought was me taking dramatic licence was actually a reflection of events that had happened since I’d last spoken to Ray, as a brave undercover agent had been ambushed and assassinated by criminals.

It was a chilling reminder of what Ray had told me – that the international pangolin trade is now under the control of organised crime and the stakes are so high that people are literally prepared to kill to protect their illegal empires.

As tragic as the event was, I hope that people become more aware of the scale of the trade, and the sacrifices good people make in the name of conservation.

TRL: Despite the critical threat to pangolins, they remain relatively obscure creatures. How do you hope your novel will contribute to raising awareness and inspiring action for pangolin conservation?

Tony Park: I think that in South Africa people are, generally, more aware of the illegal trade in wildlife and other endangered species (including plants and abalone) than in other parts of the world. I’d like to help spread Ray Jansen’s message that the pangolin is the most trafficked mammal in the world and that the sole threat to its survival is mankind. If this novel makes someone overseas get online, learn about pangolins and try to help, then it will have been worth it.

TRL: You’ve noted that wildlife trafficking ranks among the top organised crimes worldwide. What insights did your research for The Protector provide into the complexities of combating such a widespread issue?

Tony Park: For a time in the early stages of Covid-19 pangolins were blamed as the cause of the pandemic. This brought increased attention to their plight, but it also forced the trade deeper underground. This has made it harder to combat.

It’s now illegal to trade in pangolin scales, but purveyors of traditional Chinese medicine were given permission to use up their stockpiles. Anecdotally, the stockpiles are not diminishing, with the inference that organised crime is keeping up the supply coming out of Africa and into Asia. Those involved in pangolin conservation in Africa and Asia do not seem to have the profile or resources to apply pressure on governments and law enforcement agencies to do more.

As with the trade in rhino horn, probably the only long-term solution to defeating organised crime is to reduce demand – this, of course, can take years, perhaps even a generation or more. On a plus note, Professor Jansen said the South African Police Service and other conservation agencies in South Africa are doing an excellent job in busting poachers on the frontline.

TRL: After 20 years of storytelling focused largely on African wildlife conservation, what future themes are you passionate about? Are there other overlooked wildlife crises you’re keen to spotlight?

Tony Park: It seems that when I think I’ve covered all of the threats to wildlife and endangered species I learn about a new one.

My 23rd novel will look at the plight of sea turtles, which are threatened by commercial fishing. I’m very concerned about the future of Africa’s lions. There is a big market for lion bones in traditional Asian medicine and this is fed by a loophole that allows the bones of lions killed by hunters in South Africa to be exported legally. There’s pressure to close down the “canned” lion hunting industry in South Africa, and while I’m also against that type of hunting my worry is that if this happens poachers will turn their attention to wild lion populations.

So many species hang in the balance, but, on the positive side, so many people, like Professor Jansen, have stood ready to protect endangered species, even if it means risking their lives. Sadly, there will always be something for me to write about. DM

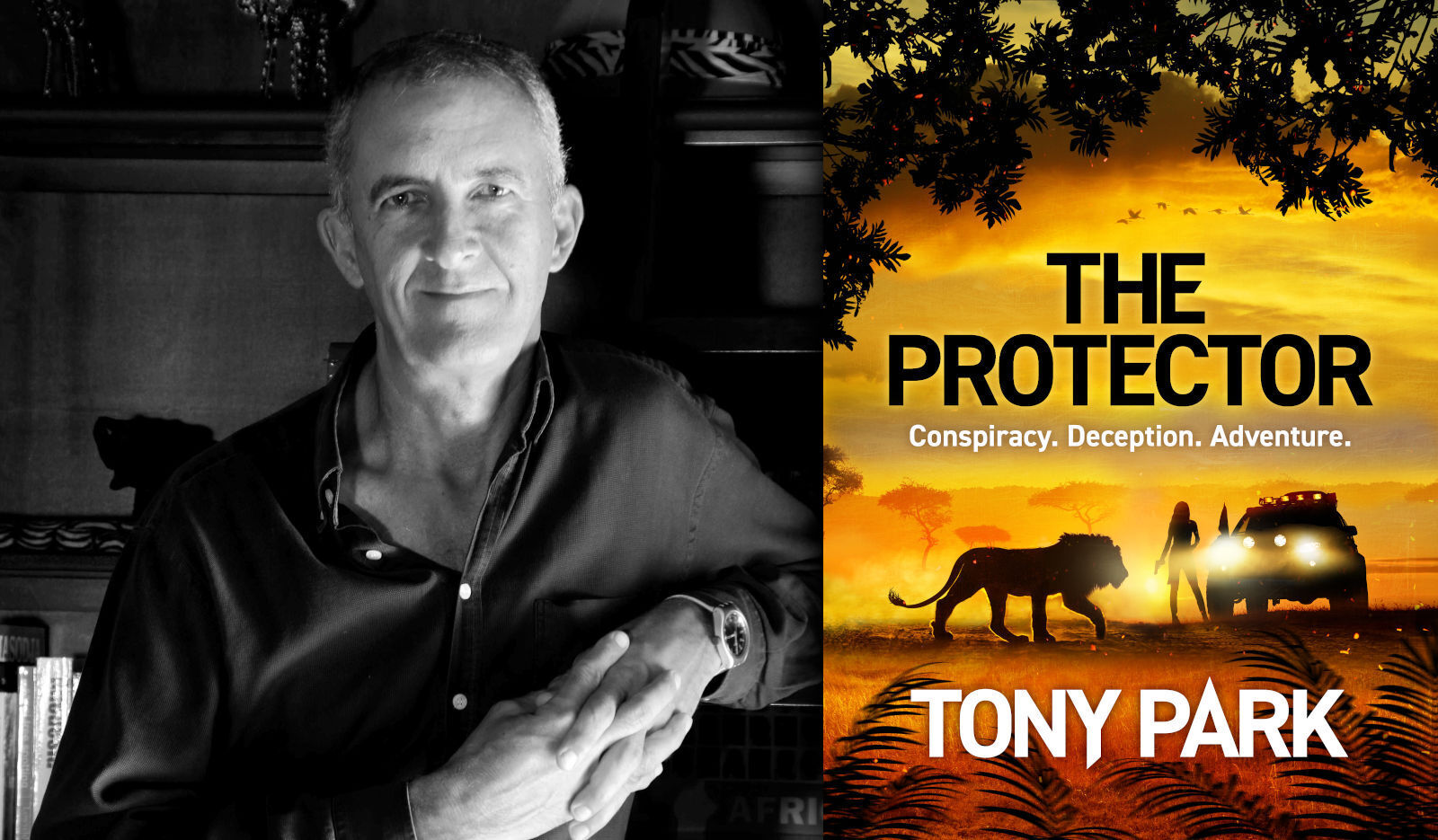

The Protector by Tony Park is published by Pan Macmillan South Africa (R350). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including interviews!

This article is more than a year old

South Africa

Undercover stings and assassinations in the illegal pangolin trade inspire Tony Park’s latest thriller, The Protector

Dubbed “the most trafficked mammal you’ve never heard of”, hundreds of thousands of pangolins are poached in Africa every year. The Reading List interviews Tony Park about his latest novel that delves into this murky world.