South Africa’s healthcare system is in dire need of a comprehensive overhaul to tackle its disease burden. The NHI Bill, signed into law on 15 May 2024, is a crucial topic of debate, aiming to ensure universal access to quality healthcare in line with constitutional mandates.

As a United Nations member committed to universal health coverage (UHC) principles, South Africa faces significant challenges due to its dual-tiered healthcare system. While the National Health Insurance (NHI) is a crucial element, the discussions surrounding healthcare financing and management are intricate and multifaceted, with various viewpoints on its efficacy.

The advent of a new coalition government presents a chance to re-evaluate these complexities. To effectively address structural and historical healthcare challenges, it is vital to consider additional factors and emerging trends in the ongoing healthcare reform discourse.

Expanding healthcare coverage not necessarily tied to social determinants of health approach

UHC covers the entire continuum of essential health services under primary healthcare (PHC), from health promotion to prevention, treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care.

While the concept is meant to be holistic, it is often viewed as a standalone health sector initiative, failing to address the broader determinants of health, such as poverty, gender inequality and education.

The broader determinants of health in South Africa, such as poverty, gender inequality, housing, water and sanitation, and education, are deeply intertwined with the country’s persistent health challenges.

Poverty and socioeconomic disparities translate into stark differences in health status, with the poor bearing a disproportionate burden of communicable diseases, noncommunicable diseases, injuries and HIV/Aids. Gender inequalities, manifested through women’s lower social status and the culture of violence, also have a significant impact on health outcomes, particularly in areas like maternal and child health.

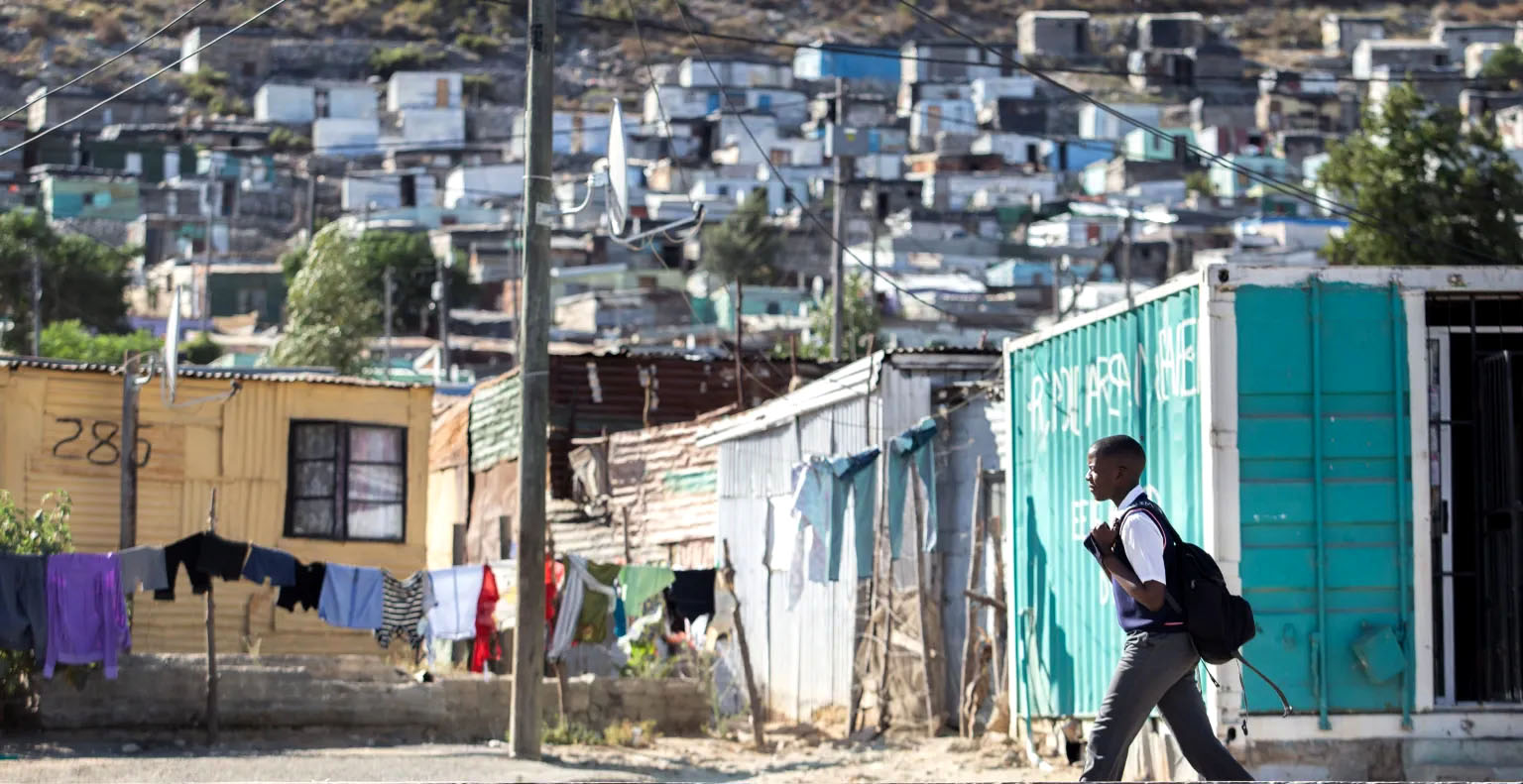

Residents of the Gate 7 informal settlement protest along Voortrekker Road between Jakes Gerwel Drive and 18th Avenue in Cape Town on 22 May 2024. They demanded services such as water and sanitation. The broader determinants of health in South Africa, such as poverty, gender inequality, housing, water and sanitation, and education, are deeply intertwined with the country’s persistent health challenges. (Photo: Gallo Images / Die Burger / Jaco Marais)

Residents of the Gate 7 informal settlement protest along Voortrekker Road between Jakes Gerwel Drive and 18th Avenue in Cape Town on 22 May 2024. They demanded services such as water and sanitation. The broader determinants of health in South Africa, such as poverty, gender inequality, housing, water and sanitation, and education, are deeply intertwined with the country’s persistent health challenges. (Photo: Gallo Images / Die Burger / Jaco Marais)

Furthermore, education levels play a crucial role, as higher knowledge and educational attainment enable individuals to make more informed choices about their health and access healthcare services more effectively.

The UHC conversation needs to address these underlying social, economic and political determinants of health that are essential for improving population health and reducing health inequities in South Africa. Tackling these root causes of poor health is crucial for achieving sustainable and equitable health outcomes in the country.

Expanding healthcare coverage does not automatically bridge gaps in service delivery

Despite global commitments, progress towards UHC remains insufficient to meet the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target 3.8, which includes financial-risk protection and access to quality essential healthcare services.

Even in high-income countries, persistent gaps in reaching populations most in need indicate a lack of equitable access to healthcare. The Covid-19 pandemic further exacerbated these challenges, halting progress on UHC and making it even more difficult to reach the 2030 targets. SDG Target 3.8 is limited to the provision of essential healthcare services, medicines and vaccines.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Everything you ever wanted to know about the NHI but were afraid to ask

South Africa has made notable progress in reducing maternal mortality, under-five mortality, neonatal mortality and infant mortality rates, with evidence of a trend towards improving UHC across different districts in the country, as measured by a UHC Service Coverage Index (UHC SCI).

For instance, the national UHC SCI value improved from 56.9 in 2016-2017 to 61.8 in the updated assessment, though this is still lower than the global estimate of 69. Provinces like the Western Cape, Eastern Cape and Mpumalanga showed the greatest increases in their UHC SCI values over time.

The remaining challenges include large gaps in UHC that still exist between provinces and districts, with a 5.1-point difference between the best- and worst-performing provinces in 2016-2017. The worst-performing district, Alfred Nzo in the Eastern Cape, only increased its UHC SCI by three points to 44 by 2016-2017.

In a similar vein, vulnerable and marginalised communities also face significant challenges in accessing healthcare. This was evident before Covid-19 and continues.

Disparities often stem from broader social and economic factors and can be influenced by gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, socioeconomic standing, citizenship status, nationality, disabilities or other variables. Prioritising equity entails recognising these obstacles and tailoring policy measures to tackle them at a granular level.

Moreover, there are substantial data gaps, particularly in key areas such as access to essential medicines, which have not been consistently tracked. To address these disparities, it is essential to enhance high-impact health interventions and establish a comprehensive monitoring framework for service coverage. This can only be achieved through collaborative efforts between the government, private sector and other stakeholders, ultimately working towards the SDGs 3.8 target of universal, equitable access to quality healthcare and essential medicines by 2030.

Higher coverage does not necessarily translate to better use of healthcare services

Despite significant efforts made towards achieving UHC, progress has been slow in numerous low- and middle-income countries. Merely expanding access to care is insufficient in efforts to attain UHC, according to a recent study focusing on UHC progress in five African and Asian countries. Expanding health services in and of itself may not be enough to ensure access to quality healthcare, since this also hinges on various factors like healthcare infrastructure, health literacy, the distribution of healthcare facilities, and local cultures.

Achieving higher use of services will necessitate a more focused approach towards ensuring quality care across multiple dimensions, including effectiveness, safety, patient-centeredness, timeliness, convenience, equality, integrated care and efficiency.

Inhabitants of a Durban municipal tent shelter on 12 March 2024. (Photo: Gallo Images / Darren Stewart)

Inhabitants of a Durban municipal tent shelter on 12 March 2024. (Photo: Gallo Images / Darren Stewart)

Furthermore, the successful implementation of the NHI necessitates a deeper understanding of factors influencing service use (demand-side factors), improved access to healthcare, a reorientation of health services towards compassionate care, more efficient delivery of healthcare services, (supply-side factors) and stronger connections between evidence, policy and practice.

These elements are pivotal for expanding intervention efforts and ensuring the NHI’s effectiveness. Healthcare systems that are established on robust PHC frameworks play a crucial role in protecting vulnerable and marginalised communities.

Out-of-pocket healthcare expenses: a precarious financial burden

In South Africa, widespread poverty contributes to significant barriers in accessing public healthcare services. Out-of-pocket expenses for healthcare, such as transport, lost income from clinic visits, and seeking private care, pose substantial obstacles to using public health services.

This situation disproportionately affects households in impoverished areas, increasing the risk of catastrophic health expenditures that can result in severe financial strain and potential impoverishment. A more comprehensive form of social protection is necessary for those living in poverty to mitigate these hardships.

The concept of a pro-poor basic income grant (BIG) has been raised, and this can be one method of reducing health inequities in South Africa. By providing a guaranteed minimum income to the most vulnerable populations, a BIG can substantially alleviate poverty and its associated health risks.

South Africa desperately needs a universal basic income grant to help bolster the economy, while also combating child malnutrition and stunting. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Nic Bothma)

South Africa desperately needs a universal basic income grant to help bolster the economy, while also combating child malnutrition and stunting. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Nic Bothma)

This is particularly significant because poverty is a primary driver of health inequities, with low-income households often facing financial constraints that hinder their access to quality healthcare. South Africa grapples with high unemployment rates and inadequate social assistance, hindering individuals’ ability to secure employment until the economy experiences growth.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Consolidated legal challenges to NHI Act will have more clout

Over the past five years poverty rates have increased significantly. The Covid grant, although temporary, prevented poverty for more than two million individuals. A BIG can fill this gap by providing a basic level of economic security, enabling individuals to make informed health choices and access healthcare services without financial burden. It can also address, to some extent, critical social determinants of health, such as housing security, education and gender inequality, which are essential for reducing health inequities.

However, the question remains on how we fund this. To sustain BIG, more discussions will be needed to focus on a combination of taxes and other revenue streams (wealth tax, increasing the tax base, closing tax loopholes, transactions tax, use of prescribed assets) so that the financial burden is distributed fairly.

A basic income grant can also address, to some extent, critical social determinants of health, such as housing security, education and gender inequality, which are essential for reducing health inequities. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Kim Ludbrook)

A basic income grant can also address, to some extent, critical social determinants of health, such as housing security, education and gender inequality, which are essential for reducing health inequities. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Kim Ludbrook)

Conclusion

Universal health coverage is a crucial step towards achieving healthcare equity, but it is not a guarantee against disparities. The NHI in South Africa poses the question of whether it will be a significant leap forward or a step backward in the country’s healthcare system.

The success of UHC will depend on various factors such as efficient resource allocation, infrastructure development, healthcare workforce capacity building, and effective governance and management of the healthcare system.

Despite the potential of UHC to transform the healthcare sector and provide South Africans with access to quality and affordable care, we need to tackle the underlying determinants of health, better understand why persistent gaps in service delivery occur, focus on improving the quality and convenience of health services, and introduce related forms of social protection that contribute to a more equitable distribution of health resources and outcomes.

A multisectoral and integrated approach that extends beyond biomedical services to include cross-cutting determinants of health is a more comprehensive approach to address South Africa’s health challenges.

A coalition government presents an opportunity to drive this transformative agenda, tackling poverty, gender inequality and access to education and healthcare.

Only a multisectoral and integrated strategic health and social development approach (financing whole-of-government action) can effectively address these challenges and pave the way to a healthier future for all South Africans. DM

Kaymarlin Govender is Research Director, HEARD, University of KwaZulu-Natal, and a member of the WHO Global Research Group on Knowledge Translation and Evidence-informed Policy-making.

Damian Naidoo was formerly with the Health Promotion Unit in the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health.

A basic income grant can also address, to some extent, critical social determinants of health, such as housing security, education and gender inequality, which are essential for reducing health inequities. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Kim Ludbrook)

A basic income grant can also address, to some extent, critical social determinants of health, such as housing security, education and gender inequality, which are essential for reducing health inequities. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Kim Ludbrook)