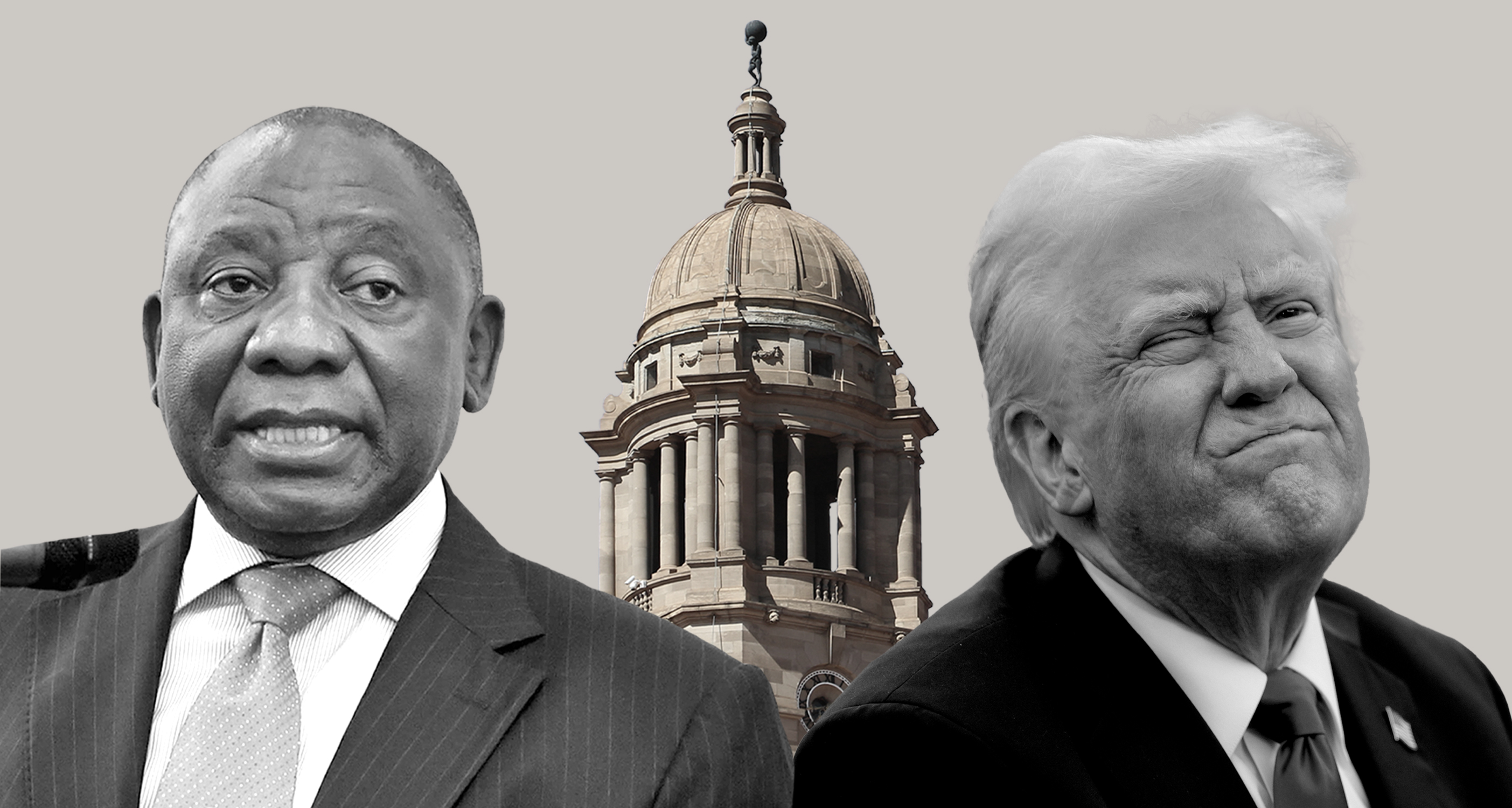

Now that the Americans and the South Africans have both had some (irresponsible) fun – the shouting, arm waving and the playground pushing and shoving – it is past time to get back to the serious business of diplomatic relations and more.

At this moment, neither country has an ambassador assigned to the other’s capital. Meanwhile, there has been shouting about those presumed insults to the American president that led to the former South African diplomat being declared persona non grata and defences of sullied national sovereignty by various South Africans.

Simultaneously, though, there is very little serious conversation about actually sorting out the challenges that divide the two nations, let alone building upon the things that already bind the two societies together. It is time leaders start behaving like adults.

It is crucial to base such a discussion on the realisation that both nations are in the midst of disruptive developments in their respective political landscapes. But it is important that any discussions about the divisions and the disconnects – and rebuilding the relationship in positive ways – recognise the respective domestic developments.

US at odds

Let’s begin with America, a nation divided politically in a way that has not been the case since the Civil War, more than 160 years ago.

The new administration, in tandem with the unelected but truly disruptive actions of Elon Musk and his corps of merry nihilists, has been ripping apart government departments and agencies and eliminating whole functions of government departments – now including the departments of education and veterans’ affairs, various regulatory commissions and the agency that administered America’s foreign assistance programmes.

Concurrently, in efforts to winnow out sources of resistance, the Trump team has been busy working overtime to remove a wide swathe of legislated checks on government such as the corps of inspectors-general, overriding the civil rights and due process considerations in its dealings with and expelling legal and undocumented aliens, and engaging in a governmental game of chicken with changing threats – or promises – of tariffs on the products of foreign nations, including longtime allies and trading partners as well as competitors such as China.

Collectively, these policy zigs and zags are triggering lawsuits and judicial pushbacks.

The usual retort from the president has been to label even conservative judges ruling against him as “radical left-wing lunatics,” with shades of Andrew Jackson’s reported response to a Supreme Court decision he disapproved of nearly 200 years earlier: “The chief justice has spoken; now let him enforce it.”

Read more: How SA can avoid stepping on diplomatic toes while dancing the Rasool rumba

All this comes in addition to a campaign undermining America’s international alliance structure – especially in Europe – something built up over 80 years. In all this, the connection with Israel has, so far, remained essentially unscathed, despite a growing wave of international criticism.

More troubling, the Trump administration has abruptly reversed his predecessor’s course in seeking closer – even subservient – relations with Russia. Crucially, he is now trying to settle the Ukraine conflict on terms favourable to America’s new partner and at the expense of the beleaguered Ukrainians.

The Trump administration’s foreign policy mechanisms draw their inspiration from the nightmare version of classic real politick ideology, mimicking the “spheres of influence” ideal in George Orwell’s dystopian novel, 1984, and advocated by such people as Hans J Morgenthau and Henry Kissinger and now on to John Mearsheimer and Jeffrey Sachs, among others.

Remarkably, this sound and fury has seen public support for the Trump administration, while slipping a bit, remaining strong, especially among Republican voters. This is consequential, given a supine Congress, with both houses controlled by Republicans with thin majorities.

The net result of these actions, often irregular, illegal and disruptive government functioning, often monopolises public thinking about government activities, leaving little space for anything else in public discourse.

Taken together, America’s official relations with friends, allies and even competitors have been thrown into confusion, and policy changes, increasingly unexplained or justified, have been done with little consideration of their impacts and onward repercussions.

Divergent views in SA

Meanwhile, as readers are well aware, South Africa’s own political universe has been hit by a slow-motion political storm of its own. For the first time since the 1994 election, a coalition government, the Government of National Unity (GNU), has been necessary after the ANC failed to achieve a majority in Parliament.

The country’s electorate has fractured significantly from the past as a collection of smaller parties and the new MK party exploded on to the electoral scene, even as the Democratic Alliance held its ground. Hard bargaining was needed to achieve that GNU, and it is a government where much consequential decision-making remains awkward.

If local psephologists are right, this landscape will persist into future elections until – or if – a true realigning election takes place among an electorate less and less connected to the saga of the ANC in reshaping the fundamental political changes of the country. Nevertheless, the socioeconomic landscape with its horrific unemployment and inequality means divergent views about the nation’s future.

In turn, this means to a considerable degree, views about the country’s international relations are also divided, including South Africa’s relationship with the US, with China, Iran, and Russia, as a putative leader of the “global south,” and its case against Israel in the International Court of Justice.

Running concurrently, and roiling waters further, is that US policy will now be offering visas to Afrikaner farmers who believe they are under threat of persecution as a result of South Africa’s new law on expropriation.

Read more: As Trump dismantles US norms and institutions, Afrikaner refugee process remains unclear

While the US is South Africa’s second-largest trading partner (and market access has been buoyed by American law, the African Growth and Opportunity Act), and South Africa maintains a trade surplus against the US, a significant portion of the electorate remains suspicious of too close an alignment with the US. That Agoa access is under threat both because the current Act expires this year and because of pressure among some Republican members of Congress to end South Africa’s beneficiary status.

Moreover, a significant share of Pepfar funding to South Africa has now been halted as part of the Trump administration’s global restrictions on foreign assistance. Further, much funding for medical and scientific research at South Africa’s premier universities from America may well be under threat if further grant cuts occur to the American research establishment or if the bilateral relationship comes under further strain.

There has even been rather loose talk about sanctioning some South African political figures under the Magnitsky Act for their presumed transgressions against democratic values.

Common ground

Given these harsh words and tensions – and most recently – naming South Africa’s ambassador to the US as persona non grata for remarks he made during a think tank webinar, it is possible to argue the bilateral relationship is almost inevitably going to spiral downward even further.

However, beyond the two governments’ disputes, connections between the two nations are – and remain —deep and extensive. Beyond the export activity noted earlier, some 600 American companies operate in South Africa, employing hundreds of thousands of South Africans and providing a wide range of training and education activities, as well as supporting a wide range of community development projects.

Beyond that corporate presence, numerous American philanthropic organisations fund a broad array of activities in the country, and there are active bilateral cooperative arrangements and exchanges between universities and cultural institutions of the two nations. And, of course, South Africans are active consumers of American cultural exports, even as South African cultural figures continue to make their marks in America.

But those government-to-government tensions are real, and will, if unchecked, negatively affect all of the above.

So, besides tamping down the reciprocal intemperate or insulting rhetoric, what must be done? Actually, there is much that can be put forward.

First of all, the two nations can, in concert, nominate thoughtful, knowledgeable, well-respected, and experienced individuals as their respective top diplomatic representatives. Perhaps in a kind of magnanimous gesture, they might even agree to announce the two individuals simultaneously as a sign of moving forward and away from previous tantrums.

Read more: South Africa and Trump – how we respond will come to define our country

The two individuals cannot be angry agent provocateurs, eager to rain fire and brimstone down on their respective postings and the nations’ leaders. They must be, in a word, diplomats – but effective ones who can set a tone of moving forward, rather than rehashing the earlier comments.

But having respected diplomats only gets one so far. There are real issues too. Pre-eminent is to create a better framework for trade and commerce. Sadly, it should be accepted that the Agoa window is likely to be shuttered for South Africa on GDP and per capita income grounds, even if the Act is renewed.

While there will be dislocations because of that, some recent studies argue the actual benefits from Agoa eligibility have been relatively minor. If so, their loss may not be the end of the world – if South Africa can find other ways to encourage and increase its exports to the US.

Accordingly, the task is to negotiate a bilateral trade agreement that includes mechanisms to encourage trade and investment and to pare back impediments to that trade and investment. More ambitiously, perhaps, it could be a joint effort in concert with a number of African nations eager to improve their terms of trade with America.

Such a negotiation would not be easy – the average trade agreement takes well over half a decade to conclude. But it should be seen as one that clearly generates reciprocal benefits – “reciprocal” being the word of the moment in Washington.

Read more: Navigating the US-SA relationship crisis means performing a delicate geopolitical balancing act

One of my earlier recommendations still holds, and that is for a bilateral forum to build (or rebuild) connections between the two bureaucracies. An earlier forum, established with great ceremony under the aegis of then Deputy President Thabo Mbeki and then Vice-President Al Gore started optimistically but eventually foundered when it promised much but delivered less, as the then HIV/Aids madness overtook too much of the bilateral dialogue.

There are obviously issues to find common ground on, even as there are areas, notably the circumstances of the Middle East, where common ground may not be found. But in calmer, less contentious settings, common ground may yet be found in many areas – even with an American administration that seems determined to pick fights with friends and allies alike.

Finally, there must also be ways to rebuild the relationship on joint funding of research in health and medicine, but in ways that point directly to the benefits to American universities and research institutions. Under the bilateral forum, perhaps that can be easier than the present negative developments as a result of Musk-inspired or impelled cuts.

Taken together, there is every reason to assume the two nations can find a better joint footing. But this will require real work and engagement, as opposed to ritual posturing. That, in turn, will depend on more skilful diplomacy than has been evident over the past several months, plus the participation from many sectors in both nations. DM