In 2018, in a landmark decision, the Constitutional Court lifted the 20-year time limit on the reporting of sexual assault. The ruling followed the case brought by the ‘Frankel Eight’, who accused billionaire businessperson and socialite Sidney Frankel of sexually abusing them when they were children.

In the wake of the ruling, sisters Claudine Shiels and Lisa van der Merwe decided to lay charges against the two brothers — their step-uncles — who had sexually molested and assaulted them in the 1970s, when they were minors.

After initially being told by the police that their case was too old — news of the Frankel Eight decision having not filtered down — the trial began in July 2020 at the Wynberg Magistrate’s Court. It has since wound its way up through the High Court and the Supreme Court of Appeals, and an application is now underway in the Constitutional Court.

“It remains to be seen if their application to ConCourt will be accepted or rejected,” Shiels says. “We consider this to be a buying time tactic. If they can avoid pleading, their names are protected. The case is now 50 years old.” Read the excerpt below.

***

Laying charges

The road at the end of Southfield, where the Zeekoevlei bus would stop briefly before chugging over Prince George Drive and off to Grassy Park on the left, looks quite different from how I remember it. So does Grassy Park. It’s a whole lot busier, too. Two sets of traffic lights now stagger the cars going in different directions and the lanes are wider. I marvel at how quickly the new can blur what stood there for decades – a century, even – sometimes making it impossible even to picture the old shops with ‘1910’ or ‘1903’ on their gables.

I drive through Grassy Park, all senses alert. I have to find the police station, plus navigate a road teeming with cars and buzzing with familiarity in some places, surprise in others. Oh my word, the mosque still looks exactly the same. Where is Busy Corner now? Wow, it’s changed. Where did that huge bus terminus come from?

I give a small ‘sorry’ wave to the irritated drivers behind me who are enduring my distracted driving.

It takes a U-turn and a stop to ask for help before I eventually find the police station. A hard wooden bench lines one wall, which quickly fills up with people clearly clobbered by life and whatever crime they are there to report. We slide along the bench as it fills from one end, and I catch the glances at me, the only white woman: What’s she doing here? Some heads hang hopelessly, not helped by the only sergeant on duty who drags himself around stamping papers and flicking his dry ballpoint to dislodge the last dregs of ink.

I am thinking they should rename it What’s the Point Police Station when it is suddenly my turn and the sergeant comes alive as I relate my story, lowering my voice as ears strain from the bench behind me. I am ushered from the front counter to the back office where phone calls are made and names jotted down. ‘They said we must go to the Grassy Park Police Station because that is where the crimes occurred,’ my sister said earlier. ‘Apparently, Zeekoevlei falls under Grassy Park. They told me that when I went to the police here in PE.’ ‘Oh, okay. That makes sense.’ ‘They took my statement, but it will be sent to Grassy Park, combined with yours, and then passed on to the Sexual Offences Unit in Wynberg. But it must all definitely happen in Grassy Park first.’ But today: ‘No, we can’t take your statement here. You must go to the Family Crimes and Sexual Offences Unit in Wynberg. We phoned them; they said you must come there.’

I clutch a grubby piece of paper with a name and ‘3rd floor’ written on it, heading out past the row of dejected eyes that watch my every move. Take us with you, they seem to say. Take us across the freeway, over there to your life … where the rich whites still live. I smile at them weakly and head out the door.

I phone Lisa when I get home. ‘I can’t go to Wynberg today, Lisa. My first visit there was so humiliating, I need to ramp up for it again. Going to Grassy Park was enough for one day. It feels unreal, like we don’t deserve it. Like, what was I doing in there when those people have terrible crimes to report?’

‘We also have terrible crimes to report, Claudine. And we have lived with it: lived with no justice, no apology, no compensation, not even an acknowledgement, for over 40 years. We have endured the crimes, the bullying into silence, the emotional effects, the psychological wounding, the deeply damaged lives … for decades. Is that not terrible, Claudine?’

A few days later, I head to Wynberg Police Station to be interviewed by a social worker and a police detective. Statements are taken and the procedure is explained to me. Embarrassingly, I cry throughout the interview, overwhelmed that I am being heard. My tears come so easily and with such force; I begin shaking in fear that something is about to be unleashed for which I have neither the strength nor the capacity.

The pain feels bigger than my body. As if, given free rein, it might burst through my skin, my organs, my mind, tearing them to shreds with its power. I do not know how to keep it tethered, imagining that it would end in insanity, or the destruction of the office in which I sit, should I let go. Help me, God, help me. The pain comes in peaks of panic, and I remember years back when panic attacks were my daily normal. Go with it. Do not retreat. Panic has a peak, it cannot go further, it dissipates. Let your lungs feel smaller and smaller, it is just a feeling, you can breathe. Even if you pass out, you cannot stop nature, your body will breathe naturally. I soar with each panic wave, and slip over the climax. My body shudders, heaves.

The kind social worker watches, unspeaking. Her eyes tell me that everything is okay. The detective sits patiently. There is no embarrassment, no hurrying. They have seen this a hundred times before. God helps me, and we eventually continue the interview.

When I leave, I feel softly peaceful and, though my legs are like jelly, they still get me downstairs and out to my car. DM

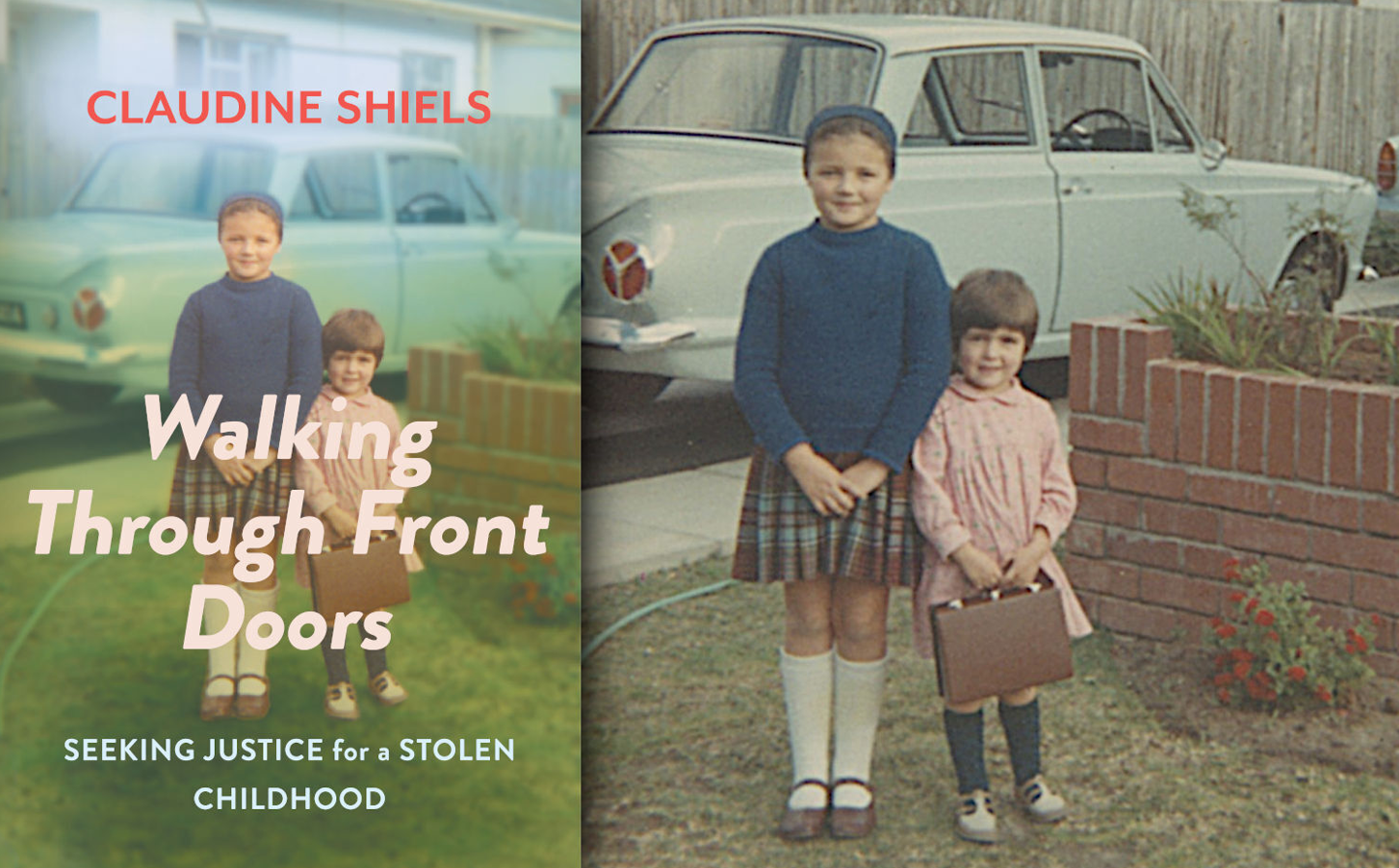

Walking Through Front Doors: Seeking Justice for a Stolen Childhood by Claudine Shiels is published by Bookstorm (R320). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!