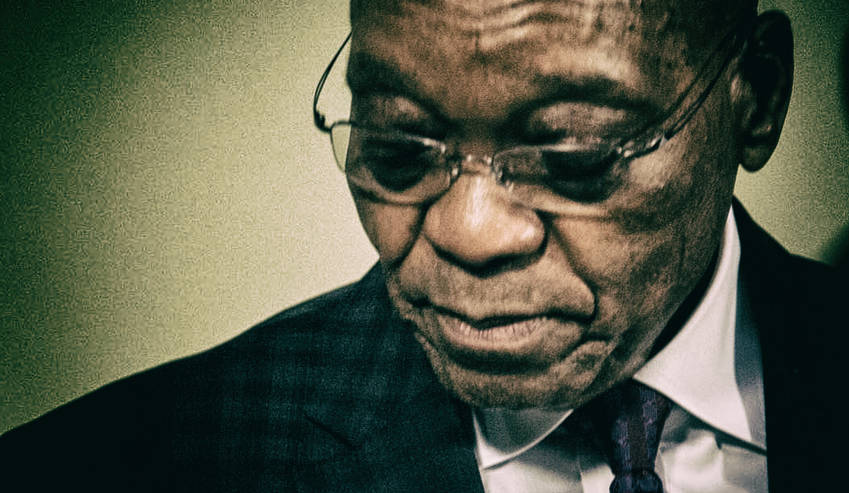

On the evening of 7 July 2021, former president Jacob Zuma was taken into custody to begin serving a 15-month prison sentence imposed on him the previous week for contempt of the Constitutional Court. The sentence was imposed after the Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, chaired by Deputy Chief Justice Raymond Zondo, argued before the court that Zuma should be jailed for defying the same court’s order that he appear and testify before the commission.

Due to the amount of deliberate misinformation and general confusion out there about how these events came to pass, it is important to set out some key facts.

A commission such as the State Capture Commission (or Zondo Commission) can only be authorised by the President. Since it was established in January 2018, that President was Mr Jacob Zuma. Announcing the appointment of Deputy Chief Justice Zondo and the commission, then president Zuma issued a statement that, in part, read as follows:

"The allegations that the state has been wrestled out of the hands of its real owners, the people of South Africa, is [sic] of paramount importance and are therefore deserving of finality and certainty. Accordingly, I have decided that, while the issues determined by the order require final determination by higher courts, this matter cannot wait any longer.”

He also added:

"There should be no area of corruption and culprit that should be spared the extent of this commission of inquiry. I trust that we will all respect the process and place no impediments [on] the commission [to prevent it] from doing its work."

Having said this, we can be justified in expecting him to testify before the commission if and when asked to do so. To be sure, in South Africa, no one is above the law, including a sitting president. This is unlike the United States of America, where a sitting president cannot be criminally charged or sued.

Once that person is no longer president, however, they can be charged for crimes committed while they were still president. In other countries, such as Israel and South Korea, sitting prime ministers and presidents have been charged and sometimes convicted. For instance, Benjamin Netanyahu was still prime minister of Israel when he was charged with corruption and fraud. Therefore, there is nothing extraordinary about charging someone in such an office.

If a president or judge were summoned to appear before a judicial commission of inquiry, they would have to appear. During the course of the Zondo Commission, President Ramaphosa and Judge Makhubele appeared and testified in line with this principle.

There have also been other senior politicians who have appeared. For instance, ANC Chairman and Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy, Gwede Mantashe, has testified more than once. Deputy Minister of State Security, Zizi Kodwa, has also testified. None of them had to be compelled to appear.

Former president Thabo Mbeki appeared before Judge Seriti’s commission to explain his role in the Arms Deal. So did former minister of finance Trevor Manuel. None of them needed to be forced by a court to appear either.

President Mandela was once summoned to appear before the high court to explain his decision to appoint a commission of inquiry into the affairs of the SA Rugby Union. It is said that he was very irritated, but he insisted on appearing despite the advice of some of his officials that he should oppose the subpoena. He wanted to show that no one was above the law, an important democratic principle.

It should be clear, therefore, that no one is exempt from testifying before a commission or court. It also goes without saying that no one should defy a commission or court subpoena either.

In Mr Zuma’s case, it must also be noted that the commission did not initially subpoena him, which is an order to appear. They chose to invite him, as they did many other witnesses who were invited to do the same. To be sure, even if they had subpoenaed him or any other witness from the beginning, there would be nothing wrong in law with that approach. They simply chose to be courteous.

To shorten a long story, after making several appearances, during which he either pleaded ignorance or took issue with being asked certain questions, he eventually decided that he had had enough and walked out of the commission without being excused by the chairman. Witnesses are not allowed to simply leave in the middle of the proceedings, but Mr Zuma did.

His lawyer, Advocate Muzi Sikhakhane, told Judge Zondo that they were “excusing themselves” from the proceedings. While saying this, he sometimes pointed his finger condescendingly at the judge. It was a stunning demonstration of personal and professional disrespect of a judge, who appears to be a naturally polite and patient person even when witnesses are being extremely difficult.

One of Mr Zuma’s complaints was that Judge Zondo was conflicted because he had once fathered a child with the sister of one of Mr Zuma’s wives, before Mr Zuma met his wife. He could not explain why he had not raised this issue when he appointed Judge Zondo to chair the commission, or on the previous occasions in which he had appeared before the commission. He also could not explain what in their “family” dealings would lead Judge Zondo to treat him differently.

That matter is before the high court. Notwithstanding, the fact that he had approached the high court to remove Judge Zondo does not suspend his obligation to obey a lawful subpoena by the commission. Having done so, the commission asked the Constitutional Court to compel him to appear. When the Constitutional Court issued an order for him to appear before the commission, he stated that he would defy its order and not appear. And, true to his word, he did not appear.

It was on the basis of that defiance that the Constitutional Court heard arguments by the commission’s lawyers, and sentenced him to serve a 15-month prison term. Mr Zuma chose not to participate in the hearing. After the hearing, the Constitutional Court directed him to make a submission of not more than 15 pages explaining why, if convicted, he should not be sentenced to a prison term. Mr Zuma told the court he would ignore that directive as well.

It was only when it became clear that he would be imprisoned that he decided to belatedly approach the Constitutional Court to rescind its decision.

There are people who contend that Mr Zuma should not be imprisoned at all because he is a former president, and because of the role he played in the struggle for freedom. This is a view that is not just held by his cultish supporters but others, too. There are also those who attribute a glowing track record of national prosperity and progress during his tenure as president that should make him immune from court sanction.

Let me explain why we cannot afford to spare him or anyone the responsibility of obeying the law.

The most obvious, narrow reason is that there is no clause in our Constitution that creates automatic and permanent immunity for anyone, no matter how powerful or revered they may be. Were that the case, a person of the stature of Nelson Mandela, who was also a sitting president, would have never been subpoenaed to testify at the high court.

Certainly, many people, myself included, were very unhappy that he was subpoenaed to testify. But it is possible to be unhappy with a court decision and still obey it.

Secondly, there are permanent responsibilities that accompany taking the Oath of Office. When he became president, Mr Zuma swore to uphold and defend the Constitution of the country. Being a president is no ordinary job but an extraordinary responsibility that goes beyond the narrow confines of the title.

It is a moral bond with all the people of South Africa that you will uphold and defend our system, whose purpose is to ensure that we are able to govern ourselves as a free people. It is absurd to suggest that once a person is no longer president, then it is okay to defy and undermine the same Constitution. In any event, it is not okay for anyone within the borders of South Africa, whether they are a citizen or not, to undermine and defy the laws of the country.

Thirdly, as a leader in many other spheres, Mr Zuma has a moral public responsibility to set a good example for others to follow. This does not just apply to matters that pertain to the courts, but good citizenship, such as not doing anything to undermine Covid-19 protocols by organising or allowing large, unauthorised gatherings. This does not only apply to him, but every leader who takes their public responsibilities seriously.

Finally, democratic institutions matter because democracy is essentially a deal based on trust. Many people with the means to defy court orders choose not to do so because it is immoral to do so. That is why our Constitution empowers the chief of the defence forces to defy an unlawful instruction from the president as commander-in-chief even if they risk being fired by the president.

There is nothing to celebrate about the incarceration of a 79-year-old pensioner who, under ordinary circumstances, should be doting on his grandchildren and enjoying the fruits of his hard labour. This is a tragic moment in that it shows that, after all these years, Mr Zuma and everyone who wants to keep him above the law have learnt nothing. As a result, they are willing to throw our entire system to the dogs in order to make one person unaccountable.

In this context, anyone who threatens public violence or actually engages in such acts, so that we have a situation where some people have the ability to simply ignore the laws of the country as they choose, must be seen as enemies of our constitutional order. If we are serious about democracy, which is not just the right to vote, then we have to hold them accountable to the system we have chosen. DM/MC