While the development of social housing in the City of Cape Town has progressed slowly, it is on an upward trajectory, according to Nick Budlender, urban policy researcher with the non-profit housing rights law centre Ndifuna Ukwazi. The past few years have seen new developments reach completion, as well as a spate of land releases for future projects.

The Social Housing Portal, a database tracking the provision of well located social and affordable housing in South Africa, indicates that 5,092 social housing units were built in the city of Cape Town between 1997 and 2023.

https://uploads.knightlab.com/storymapjs/969af7d83d45bf42d5090973b9854f06/interactive-map-showing-key-social-housing-sites-in-cape-town/draft.html

“In my mind, almost all of the existing social housing in Cape Town is a success story because it offers families access to areas that they would never be able to access through any other form of government assistance. (The Social Housing Programme) is the only housing programme that targets well located areas,” said Budlender.

“The City of Cape Town clearly currently takes it a lot more seriously than they used to, and not only have we seen quite a few pieces of land being released recently, but we also have seen some really nice projects come on line in the past few years. For instance, Maitland Mews is a very nice development of pure social housing in Maitland, in a very well located area near to jobs and schools and hospitals and everythings else.”

However, there remained a number of projects promised in the early 2000s that had yet to be delivered, he said.

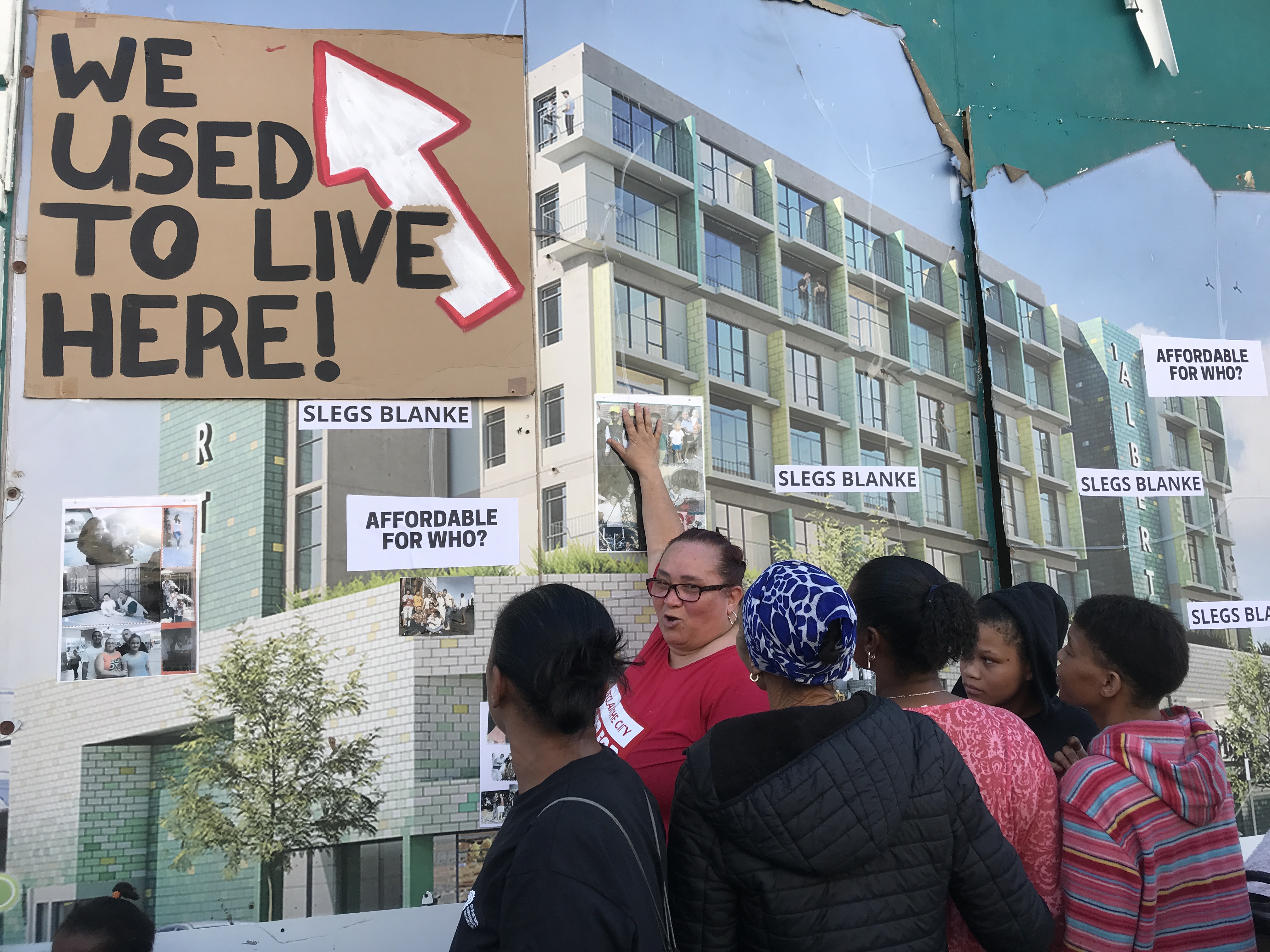

Over the years, activists from Ndifuna Ukwazi and housing rights non-profit organisation Reclaim the City have argued that the City of Cape Town has moved too slowly when it comes to issues of spatial injustice and the housing crisis.

Read more: Housing crisis protesters brave heavy downpour during all-night vigil at Alan Winde’s residence

Budlender noted that while there were a number of factors that had hindered development, one of the major challenges facing the social housing sector was the limited funding for the Social Housing Programme coming from the national Department of Human Settlements.

What is the Social Housing Programme?

The National Department of Human Settlements’ Social Housing Programme is intended to address the increased need for affordable rental units that provide secure tenure to “the upper end of the low-income market”, with the primary objective of urban restructuring and creating sustainable human settlements.

The programme provides grant funding to establish social housing institutions that can develop, own and manage affordable rental units in different areas. These social housing institutions are non-profit companies with accreditation from the Social Housing Regulatory Authority, a public entity under the National Department of Human Settlements.

According to the Western Cape government, social housing is an affordable rental option for households earning between R1,850 and R22,000 per month. Other criteria for qualifying for social housing are determined by the Social Housing Act (No. 16 of 2008) and the Social Housing Regulatory Authority.

How does social housing work in Cape Town?

The National Department of Human Settlements determines the overall policy for social housing and passes grants or subsidies to the Social Housing Regulatory Authority. The public entity then disperses those grants to approved social housing projects, according to Budlender.

He explained that the process for delivering social housing differed between cities. In some regions, provincial Departments of Human Settlements is responsible for identifying potential sites and driving development.

“In a city like Cape Town, that is very much the City’s responsibility… The City’s role is to identify land, and make land available that it owns to support these projects, do the planning and really try to drive them through in collaboration with the social housing institutions responsible for the specific projects,” he said.

“Cape Town has basically been assigned a large part of the housing function after it applied for accreditation some years ago.”

Speaking during a Daily Maverick webinar on housing and homelessness in August, Cape Town Mayor Geordin Hill-Lewis noted that once a social housing project was handed over to a social housing institution such as a Communicare or the Social Housing Company, the City became a partner “holding the hand” of the company while it completed the development.

“There’s also a time when it becomes out of the City’s hands. We hand over the subsidy, we hand over the land, we do the discount… We’ve actually codified, for the first time that I’m aware of… the rules in our council policy documents as to how we will discount the land, all the way down to zero if necessary, so that we can get the maximum possible social housing benefit,” said Hill-Lewis.

“All of our projects… have a detailed budget, which is freely available. You can see exactly what housing projects are budgeted this year, and every year for the next three years. We have a three-year budget cycle.”

According to the City of Cape Town, it has nothing to do with the day-to-day management of social housing institutions, the rental amount at sites or evictions for not paying. The institutions are solely dependent on rental income and receive no operational grants.

What’s hindering social housing progress in Cape Town?

There are some practical challenges when it comes to releasing land for social housing in Cape Town, such as the high land value in the metro, according to Budlender.

“Cape Town, especially in the well located areas, is very, very expensive. We have a city bowl that’s hemmed in by the sea on one side and the mountain on the other, which really does have quite an effect on urban agglomeration… and the prices of land and housing there,” he said.

Budlender claimed that historically, there had been a “deep political resistance” to the idea of building social housing in the City of Cape Town. This opposition within the City had scuppered progress on some projects that had been stuck in the pipeline for more than 20 years, he said.

Hill-Lewis has stated that he doesn’t believe the City of Cape Town was ever opposed to social housing.

“I think what I have learnt about social housing is that it’s unbelievably complex and difficult to actually get through the system… There’s something called the municipal asset transfer regulations, and a mountain of red tape that is involved in getting a piece of land through the system out to market, especially if you want to discount that land, which is essential if you want to deliver affordable housing,” he said.

“We certainly have ramped up delivery… We’ve released more parcels of land in the last two years than in the 10 years before that. So, there has been a dramatic increase.”

The old Woodstock Hospital, renamed Cissie Gool House by its occupiers. (Photo: Ashraf Hendricks)

The old Woodstock Hospital, renamed Cissie Gool House by its occupiers. (Photo: Ashraf Hendricks)

In recent years, the City had done a lot to drive the development of social housing and release land for this purpose, acknowledged Budlender. He identified one of the major barriers in the current social housing market as the inadequate funding provided by the national government.

“I think the biggest change that happened is that in April 2023, the national minister of human settlements announced that the subsidy amounts for individual social housing projects would increase dramatically, but there was no increase in the overall subsidy envelope that was available, which now meant that you had the same amount of money overall, but fewer projects could get serviced,” he said.

“That has been an absolute and utter disaster. Projects that were ready to be launched in one year’s time… are now looking at eight, nine, 10 years. A huge amount of work has gone into getting Cape Town into a position where there now is this pipeline of land for social housing and a very rash, poorly considered and poorly consulted decision has now scuppered all of that progress and thrown both the municipality and the entire social housing sector into an incredibly precarious position.”

Budlender added that there was a risk social housing providers would be pushed out of the sector if they continued to face difficult operating environments and delays to projects.

“The budget overall for social housing is set by the national government and is about R860-million, which is roughly 2,9% of the overall human settlements budget. That’s really small, actually, when you consider how much they speak about social housing, how much they speak about reversing spatial apartheid, reintegration and bringing people closer to economic centres,” he said.

Daily Maverick reached out to the national Department of Human Settlements about these issues, and a response will be added if one becomes available.

Where do illegal occupations stand?

The City of Cape Town has stated that illegal occupations on public land are a barrier to the development of social housing.

Two notable occupations in the metro are Cissie Gool House, formerly known as the old Woodstock Hospital, and Ahmed Kathrada House, on the site of the old Helen Bowden Nurses Home in Green Point. Both sites were occupied in 2017, as part of a campaign by Reclaim the City, in protest against the City’s alleged failure to deliver affordable housing opportunities in the inner city and surrounds.

In August this year, GroundUp reported that the Council of the City of Cape Town had decided to go ahead with a public participation process to release the old Woodstock Hospital site for the development of affordable housing. Hill-Lewis claimed that social housing would already be in the construction phase were it not for the illegal occupation, and estimated that 500 homes, including both social and affordable housing units, could be made available.

Ndifuna Ukwazi released a statement questioning why other social housing projects on unoccupied sites in the area had also seen little tangible progress. It advocated for the City to engage with the occupiers about the approach to the proposed development.

Bevil Lucas, a resident of Cissie Gool House and leader at Reclaim the City, told Daily Maverick that moving into the occupation had afforded people the opportunity to participate in the remaking of a community that came from a history of displacement.

“It affords people better quality schools, it affords people the opportunity to find employment, and more regular employment… The fact that people have been able to find employment in those spaces affords them the opportunity to participate as citizens living in the community, living close to the city – to live a normal life, albeit under very abnormal circumstances,” he said.

He echoed Ndifuna Ukwazi’s call for the City to engage with communities that stand to benefit or be affected by the development of social housing.

What are some social housing success stories?

In June of this year, the City of Cape Town announced that it was set to release its sixth inner city property for social housing development following Council approval – the 9,000 square metre New Market Street property in Woodstock, which would yield 375 social housing units and more than 350 open-market residential units.

“The City has now released central Cape Town land parcels with an estimated yield of more than 4,900 affordable housing units, including 2,100 social housing units. Sites include New Market Street, Pine Road, Dillon Lane and Pickwick in Woodstock, as well as Salt River Market and the now tenanted Maitland Mews development, with more in the pipeline,” stated the City.

In recent years, some of the developments that have reached completion include:

- Conradie Park, completed in 2020 with 432 units.

- Maitland Mews, completed in 2023 with 204 social housing units.

- Goodwood Station, completed this year with 1,055 units.

“What we are seeing more is an increasing call to mix social housing with other uses. So, those could be shops or offices or market-rate housing as a way of trying to increase the viability of projects and to better take advantage of some of these very strategic pieces of public land which are forming part of the social housing programme,” said Budlender.

“We haven’t really seen many examples of that coming to fruition yet. There’s one that’s unfolding now at Conradie (Park) which is a big, provincially driven project out in the Pinelands/Thornton area, and that has a mix of all sorts of types of affordable housing and some market-rate housing, and that looks like it’s going successfully so far.”

What role does social housing play in Cape Town’s future?

In September, the City of Cape Town released the draft Local Spatial Development Framework for Cape Town Central Business District (CBD) for public comment. In the Cape Town CBD Transition Plan, it was noted that there was a total theoretical unmet residential demand of 17,000 to 21,650 new residential units, spread across market and affordable income brackets, for the period up to 2040. This meant the CBD would need to accommodate between 40,000 and 50,000 more people by that point.

“I think that Cape Town will continue to grow substantially… People of all incomes are obviously going to move to where they think they might get some better services, and that’s a reality we should acknowledge, but that will place real pressure on the city,” said Budlender.

He advocated for a pragmatic, evidence-based approach that gave people access to land and tenure security, and supported them to build houses for themselves, on top of the provision of state housing. However, he said this would require a significant change to the current management of the sector.

“Because the formal private sector doesn’t provide housing that gets anywhere near people’s incomes, and because state housing delivery has collapsed so spectacularly in recent years, the vast majority of the new housing that’s developed will be informal. So, you’ll see more informal settlements, the growth of informal settlements and I think that’s really going to be the story of Cape Town’s urban growth in the next 10 years, much like it has been in the previous 10 years,” he said.

Eddie Andrews, Cape Town Deputy Mayor and Mayoral Committee Member for Spatial Planning and Environment, stated that the provision of affordable housing was a key part of realising the local spatial development framework for the CBD.

“The Local Spatial Development Framework intends to transform the CBD into an environment that is more people-centred with urban design interventions to improve mobility and access for pedestrians, efforts to optimise heritage areas, a public land programme to inform land release in support of affordable housing opportunities, and an appropriately scaled urban form and interface to encourage mixed-use intensification,” he said. DM

The old Woodstock Hospital, renamed Cissie Gool House by its occupiers. (Photo: Ashraf Hendricks)

The old Woodstock Hospital, renamed Cissie Gool House by its occupiers. (Photo: Ashraf Hendricks)