An enduring problem that both apartheid and current administrations have been unable to tackle effectively is that of unlawful occupation of land.

The problem of vacant buildings has garnered global interest in recent weeks following the heartbreaking loss of 77 lives in Marshalltown, Johannesburg. Following the devastating fire, we were astonished to witness politicians placing blame on NGOs for the catastrophe and taking the City of Johannesburg to court for previous illegal evictions.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Joburg's heart of darkness: Inside the inner-city housing crisis

While there are numerous aspects to this discussion (with much yet to be explored), I’d like to centre attention on a specific facet, which is the instinctive tendency to resort to force as a response to the removal of unlawful occupiers.

The backdrop to this situation doesn’t involve unlawful occupation in Johannesburg, but homelessness in Cape Town. In essence, both situations revolve around the government’s approach to addressing unauthorised occupation of public land.

Some context: Past and recent past

The root cause of land occupations can be traced back to the two fundamental pillars of the migrant labour system and the forced removals inherent in successive colonial administrations. Colonial administrations grappled with a paradoxical challenge as they sought a cheap source of black labour while simultaneously desiring to keep these labourers at a distance from exclusively white urban areas. As Hendrick Verwoerd explained in 1958:

“Whites have their rightful home and there the Bantu is the temporary inhabitant and guest, whatever the reason for his presence may be... The Bantu residential area near the city is only a place where whites provide a temporary home in their part of the country for those who require it because they are employed by them and earn their living there.”

While this may have been sustainable for them for a while, in the 1980s, South Africa experienced rapid urbanisation, marked by significant population shifts from rural to urban areas. This led to the growth of informal settlements or squatter camps on the outskirts of major cities.

These areas lacked basic infrastructure, such as clean water, sanitation, and electricity. The government often bulldozed these settlements in an attempt to control urbanisation, leading to protests and further tensions. Urbanisation exacerbated social and economic inequality, ultimately playing a pivotal role in reshaping South Africa’s political environment and leading to the downfall of the apartheid regime.

The 1951 Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act

It is a misconception to believe that the use of force was not, in fact, devoid of legality. One such instrument used to effect racial segregation was the 1951 Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act (Pisa). This act was used as a legal tool to forcibly remove black, coloured and Indian classified communities from areas designated as “white” under apartheid policies.

Penalties for unlawful squatting included fines and imprisonment, further reinforcing the apartheid regime’s control over these populations. It granted authorities the power to evict and relocate people deemed to be unlawfully squatting in these areas. It worked in tandem with the Population Registration Act of 1950 where formal classification determined where individuals could live, work, and access services.

During this era, politicians too lashed out at NGOs for representing communities subject to forced removals. In a speech made to the House of Assembly in 1977, SJM Steyn of the National Party remarked that:

“It is clear that there are other forces at work, forces whose object it is to encourage and perpetuate squatting in order to foment racial dissatisfaction and racial hatred and to discredit the government and South Africa. How else does one explain the recent court cases which were aimed at thwarting the authorities when they wanted to take steps to put an end to illegal squatting, which constitutes a danger to society?”

Fast-forward to the post-apartheid-era

Post-apartheid South Africa introduced progressive legislation to protect the rights of unlawful occupiers and prevent illegal evictions. The Constitution of South Africa (1996) and the Prevention of Illegal Eviction from and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act (PIE Act) of 1998 set out legal procedures that must be followed for eviction. The PIE Act decriminalised “squatting” on private and public land, which was prohibited by Pisa.

Despite these legal safeguards, some landlords, property developers or government officials continue to flout the law and forcibly remove people from their homes. While there have been concerted attempts to evict communities outside of the PIE Act, it would be a mistake to assume that there isn’t also a deliberate effort to misuse laws for illegal evictions.

Which brings us to the 2021 City of Cape Town Streets, Public Places and Prevention of Noise Nuisances By-law (streets by-law).

This law traces its genesis back to British “vagrancy” laws which were implemented in the Cape Colony in 1809 and which disproportionately affected the nomadic indigenous people of the Cape, namely the Khoi and San.

The streets bylaw regulates various aspects of public behaviour and the use of public spaces. This can include rules about street vending, public gatherings, cleanliness, and more, which aim to ensure the orderly and safe use of public areas. One such rule is a prohibition against camping or sleeping overnight that is applicable across urban areas, curiously except for informal settlements. In short, it’s a prohibition against homelessness enforced only in urban centres and affluent suburbs.

In terms of the streets bylaw, if found contravening this rule and a homeless person refuses to move to a homeless shelter, law enforcement can impose a fine, effect an arrest, and impound the material used to make an informal structure.

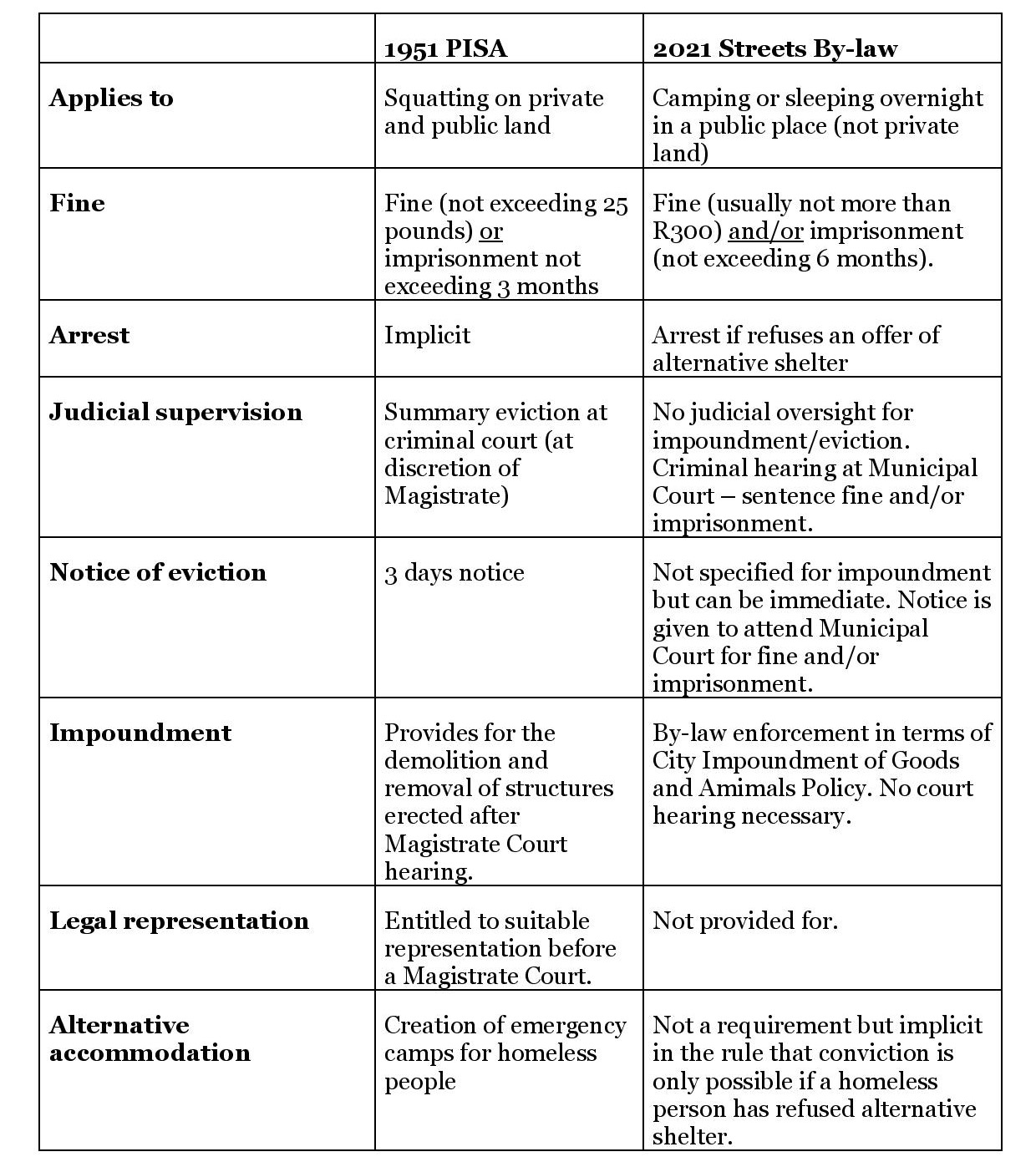

So, what is worse: the 1951 Pisa Act or the 2021 Streets By-law? Here is a table that provides a direct comparison:

In my evaluation, it appears that, while somewhat similar, the repealed 1951 Pisa included provisions for greater judicial supervision, the option to have legal representation during eviction proceedings, the necessity of formal notice before an eviction order can be issued (three days as opposed to no notice), and is less severe in terms of the criminal penalty imposed (three months as opposed to six months).

The irony lies in the fact that at the peak of apartheid, the impoverished had more legal safeguards than they currently possess in the post-apartheid democratic era. While the Western Cape administration emphasises its commitment to the rule of law, this situation bears a resemblance to the apartheid regime, which was essentially built on institutionalised segregation and racism.

Although these laws may not overtly target specific racial groups, the punishment of poverty inevitably harms the most economically disadvantaged members of our society, who have historically been black, coloured and Indian, dating back to colonial times. DM