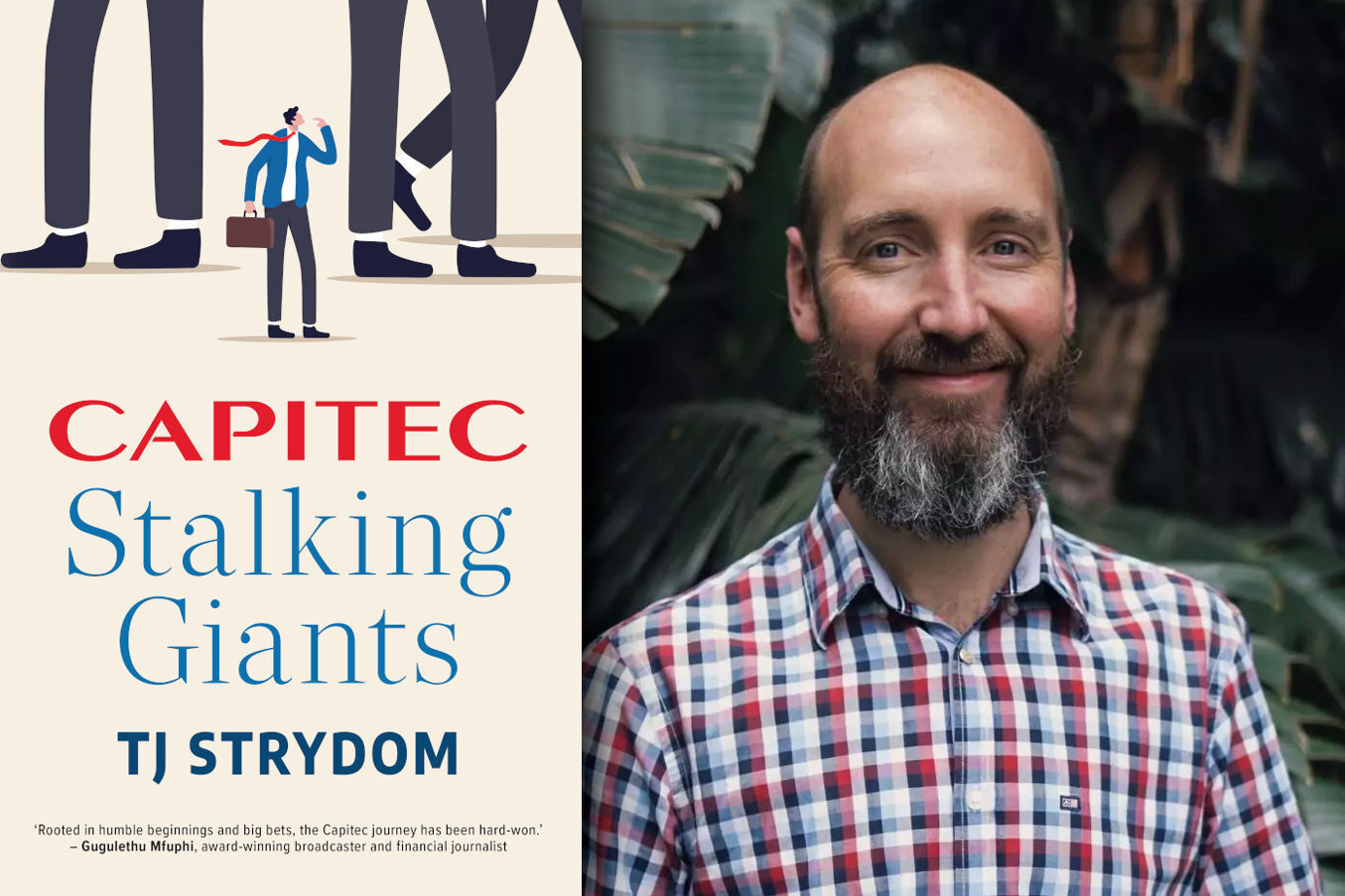

In Capitec: Stalking Giants, top-selling business author TJ Strydom tells the gripping tale of a small team of entrepreneurs that turned a small microlending network into a challenger bank.

With their luxurious head offices in Johannesburg, the giants disregarded the small Stellenbosch upstart. But once the new bank gained momentum and started luring customers away from the staid establishments in droves, they were forced to take note.

By opening branches while the other banks were scaling down, focusing on personal interaction while the others were automating, and offering services to those South Africans written off as “unprofitable” by the big four, Capitec bank became the biggest success story of the new South Africa. Read an excerpt below.

***

The banking banquet

For decades, it was fun to be a big bank in South Africa. Sure, the politics were complicated and the markets were turbulent, but there was good money to be made from the country’s white middle class. Smaller competitors could be a bother at times, but after a swift kick they mostly disappeared with little more than a whelp.

By the 1990s the corporate head offices of the old giants took up entire street blocks in the glitzier parts of Johannesburg’s CBD. Clients were used to banking halls of heavy wood and pale marble, hushed like old-world cathedrals. Behind bulletproof glass or bars of solid steel stood know-it-all tellers. Banking was serious and these spaces were a place to be humble. If you did something wrong they made you feel small. That queue, that form filled in this way, not that.

In the back rooms herds of banking personnel roamed around making mysterious entries in files, leaving a paper trail deep enough to fill encyclopedias. It was the sort of bureaucracy that would give Kafka fever dreams. It, nonetheless, turned into a massive money mill. Costs were high, penalties were stiff, and from institution to institution it was all just about the same.

It was a machine – an exclusive group who slotted together cleanly and colluded informally, but technically stayed within the letter of the law. The old giants could afford to turn their noses up at the “unbanked” – the millions of black South Africans who had for decades been excluded from formal banking services, but who collectively represented a massive untapped market.

Read more: ‘Koos Bekker’s Billions’ – TJ Strydom delves into a private billionaire’s life, career and business decisions

The conventional wisdom preached by the decision-makers at every big bank was that it would be uneconomical to service these clients because their transactions were simply too inconsequential. Not only were they unbanked, but the large institutions in effect viewed them as unbankable. It was not the banks’ responsibility to help them, that was a job for non-profit organisations. This part of society, if you follow the logic of the sector at the time, was a charity case. Only after they had been groomed for formal banking would they be able to share in the benefits that the banked minority was “enjoying” at great cost.

This was, of course, bullshit. No one enjoyed banking. And who would benefit if clients were groomed just to be milked dry thereafter? How could an advanced banking sector not be able to develop a suitable business model for such a large market?

For years, Absa, Nedbank, First National Bank and Standard Bank fed at the trough. But a big meal makes you drowsy. And while the giants were napping an unlikely competitor was waking up to new opportunities.

Just after the turn of the century, and without spending a cent on advertising, a blue-and-red logo made its appearance in the town centres of South Africa. Where those without bank accounts were queueing to take their buses, taxis or trains home, modest shops started popping up. These branches went back to the very roots of banking: they provided financial services to the man and woman on the street.

The word “bank” is from the Italian banchieri, which referred to a person sitting behind a bench. In the late fourteenth century, bankers on the streets of Florence, Venice and Rome sat there selling a product. They were selling money. Clients queued and then, after a transaction, walked away with bags of coins. But if you were buying money, what were you paying with? With a promise, of course – the promise that later you would bring back even more money. Or, if it was the other way around, you could deposit your money so that the banker could lend it to someone else with the promise of giving you even more money later.

For thousands of South Africans, then hundreds of thousands, then millions, this centuries-old practice was just what they needed. Basic banking services: borrow, save and conduct simple transactions. Basta, as the Italians would say, with luxurious banking halls and shiny head offices.

The new bank had the name Capitec, a combination of the words “capital” and “technology”, because what else was a bank but a pool of capital distributed by a group of people using clever technology?

Behind the business was a bunch of guys from the Boland. You might think the founders would pronounce the name with an Afrikaner accent. Capitec with a K? Not so. Although they speak mostly Afrikaans, the name rolled off their tongues in smooth English. The bank they designed might be headquartered in Stellenbosch, but it’s an institution to serve the entire nation.

Does a bank have a soul, a personality, a look? Probably, yes. A traditional bank makes you think of a dapper middle-aged bureaucrat, slightly overweight, but not to the extent that a grey-tailored suit would be a bad fit. Cufflinks on the sleeves, ballpoint pen in the top pocket, and a framed photo of a spouse and 2.3 children on a shiny Imbuia desk. And a secretary carrying in correspondence and pouring coffee.

And what would Capitec look like if it were human? A bulky guy, naturally, who would tuck his checked shirt into his blue jeans. Those thick soles of his shoes were made for walking and matched the brown leather of his belt. It’s the sort of uniform a go-getter wore every day. Though he did not work outside, he has a face that sees the sun regularly. He would not start a bar fight, but when the action became unavoidable, he would say, “Liefie, hold my beer.”

By the time the old giants were clenching their fists, it was already too late. Like a python, Capitec had been measuring them up for years. With low costs, clever marketing and a simple approach, the new bank wrapped itself around these competitors and squeezed the life out of them.

In 2016 the Lafferty Group, a banking consultancy with tentacles in 150 countries, rated Capitec the best bank in the world. Adjudication was based on a variety of financial and other measures, and the South African bank was the only institution to be awarded five stars. The following year the news agency Reuters called Capitec “The Budget Bank Rattling South Africa’s Financial Sector”. Years of clever innovation and gradual positioning had given Capitec an almost unstoppable momentum.

By 2024 Capitec’s client numbers had swelled to more than 22 million and its market cap exceeded R300-billion. At the time of listing, after that first day of trading in 2002, the company had been worth a mere R100-million. That is some growth! Arguably the greatest wealth-creation exercise South African shareholders had seen this century, rivalled only by Naspers’ windfall from its investment in the Chinese technology whale Tencent. A large part of the compound growth now sits in the retirement funds of millions of civil servants and private sector workers.

Far more important is the social impact. Whereas, at a time, banking services were only available to a well-to-do minority, now anyone with an identity document, proof of address, and a few rands he or she wants to move from here to there has access. This is partly as a result of the lower cost – Capitec’s arrival forced the old giants to adjust their own prices downwards – but is actually the simplification of the bank’s offering that resulted in a revolution of sorts; call it a peaceful transition from an unfair past to a more hopeful present. Should Capitec get the credit?

In 2001, which Capitec sees as the year of its birth, around 17,6 million South Africans were outside the financial sector looking in – the unbanked, the economically excluded. By 2023 this had shrunk to 3,6 million. Take into account that the country’s population had increased from 47 million to 60 million over the same period, and it is clear that a massive shift in access to formal banking services had taken place in a mere two decades.

But how did it happen? Building a bank in this country must be near impossible, with capital requirements so enormous, systems so unaffordable, and the regulators and other gatekeepers so stingy with their licences and membership.

And, yes, the founding of Capitec was no fairy tale. It was a rough-and-tumble beginning that included a bunch of opportunists, a team of builders, and, throughout, an uncertain future.

Today Capitec’s head office is a shiny beacon on a hill outside Stellenbosch. But the story doesn’t start in this stately old town with its oaks and elegant white gabled buildings. In the somewhat untamed rural Limpopo, at the time still called the far northern Transvaal, it all started with peanuts. DM

Capitec: Stalking Giants by TJ Strydom is published by Tafelberg (R320). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!