Voter turnout can play a critical role in elections and will likely shape the balance of power between political parties in 2021. Turnout determines the vote share obtained by the governing party vis-à-vis the opposition parties. Moreover, a turnout differential between partisan groups that favours one particular party over others can help that party march to victory without it having necessarily expanded its support base.

Similarly, if supporters of a particular party disproportionately fail to turn out to vote on election day it effectively suppresses their percentage of the vote share vis-à-vis other parties, regardless of increases in the number of votes for other parties.

At the 2016 municipal elections, the ANC’s losses were exaggerated by a huge stay-away among its core support base and by the DA’s ability to mobilise its own support base to vote in larger proportions across the highly contested metropolitan areas. A greater proportion of the ANC’s support base than witnessed before decided to abstain from voting, whereas the DA was more successful at mobilising its supporters to cast a ballot on the day. This resulted in a disproportional increase in the percentage vote share for the DA, not because the party had necessarily attracted huge numbers of new supporters outside its traditional heartlands, but because ANC voters had failed to participate.

This was an unusual situation for the ANC. Survey data repeatedly shows that ANC supporters are always more likely to turn out on election day than opposition supporters, and far more likely to vote than the increasingly larger numbers of non-partisans in the electorate.

At recent elections, however, ANC supporters have increasingly declined to vote, and the turnout differential between the ANC versus its closest competitors has started to close. This trend, no doubt, occupied ANC election strategists in the last few months as they correctly geared their election campaign towards simply mobilising the party’s disillusioned support base rather than focusing on clever electioneering slogans.

Yet, the DA may suffer the same affliction. The 2016 election was the last apparent increase in growth for the party at any election. By 2019 the DA suffered losses and performed poorly, with its share of support from the voting-age population dropping for the first time and attracting half a million fewer voters than it did in 2014. That the DA may also be on the back foot in terms of mobilising its core constituencies may affect its results in 2021 across the key municipalities that it won in 2016, mostly through coalitions.

However, if both the larger parties fail to mobilise their partisan bases in relatively equal proportions, the net effect on the election results across municipalities will be negligible. However, this should benefit the smaller parties disproportionately because it will effectively increase their combined vote share percentage against the larger parties. This is a likely scenario.

Both the ANC and DA currently suffer credibility deficits within their own support bases. The ANC has haemorrhaged support due to poor performance while the DA’s seemingly endless internal battles has brought uncertainty about where it stands on issues, but more importantly, who it represents. This has cost the party old, traditional constituencies while limiting its ability to attract large numbers of new voters.

This paves the way for smaller parties, including the EFF, to maximise on voter disillusionment and uncertainty towards the larger parties by focusing on mobilising their far smaller pockets of supporters to vote. Key to the fortunes of smaller parties are not only those disillusioned voters that are casting about for new political homes but primarily the increasing numbers of “floating voters” in South Africa who are unattached to any particular party. These potential voters are the most difficult to mobilise — mainly because they lack an affiliation and thus a motivation to cast a ballot — and their inactivity at recent polls has caused aggregate turnout to decline. However, many do vote and are the most able to move their support across the party landscape and consider smaller parties and independent candidates as viable options.

If large numbers of non-partisan voters decide to vote and support smaller parties this could transform the local political scene, as they become kingmakers in coalitions and are offered opportunities to flex their weight disproportionally in local councils.

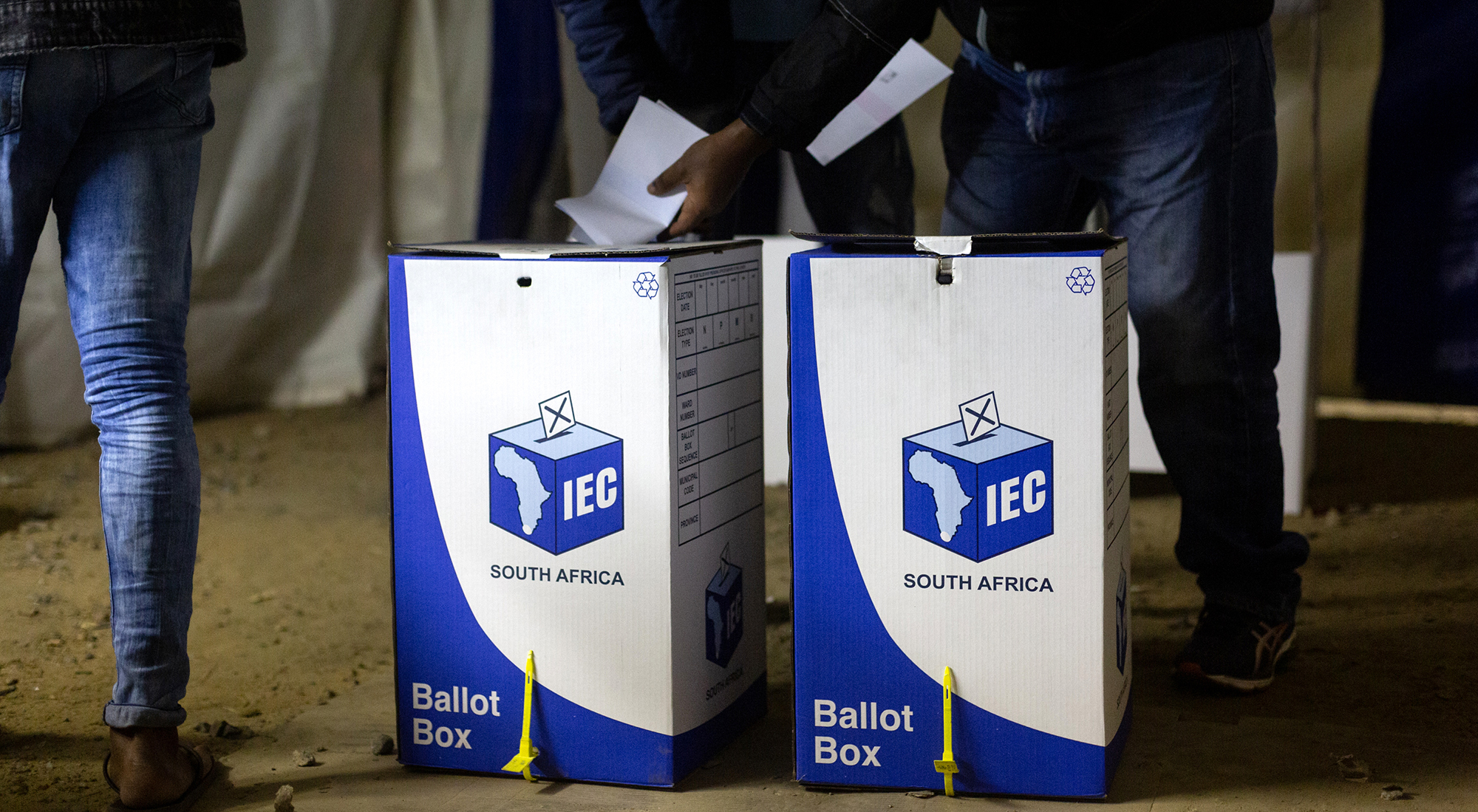

There is a higher number of parties and candidates than usual registered for the 2021 elections, prompting the IEC to note that this is the most contested municipal election yet. The level of political competition at elections plays a role in determining turnout. More competitive elections increase political interest among voters and mobilise people to vote.

Uncertainty over election outcomes also matters. If people think their preferred party can win but are unsure of the margin of victory, or perceive a tight race, they understand that their vote becomes critical, and they are more likely to vote. The competitive character of the 2016 elections produced fiercely fought campaigns in several urban metros, and given the disproportionate focus again on the large urban municipalities by party campaigns, we can expect tightly fought election battles again.

The effects of the turnout differential will be most apparent in these urban settings because municipal elections have smaller geographical election boundaries. Thus, the losses incurred by abstentions in urban areas cannot be offset by the relatively higher vote shares the large parties may attract in rural areas, as is the case in national and provincial elections.

The effects of voter turnout are often masked or obscured by the focus on the election results. Yet, turnout tells us much about underlying behaviour within the electorate. It is also regarded as a crucial barometer of the vitality and health of a democracy. High turnout is a sign of a politically involved electorate while low turnout signals indifference, disenchantment, apathy or even distrust.

Whatever the reasons for the decline in voter turnout in South Africa in recent elections, for the 26 million registered voters, their vote is crucial to the representation of all citizens and can even shape the party system for years to come. DM

Dr Collette Schulz-Herzenberg is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at Stellenbosch University.

South Africa

With ANC and DA both facing credibility deficits, voter turnout is a key factor in the local elections