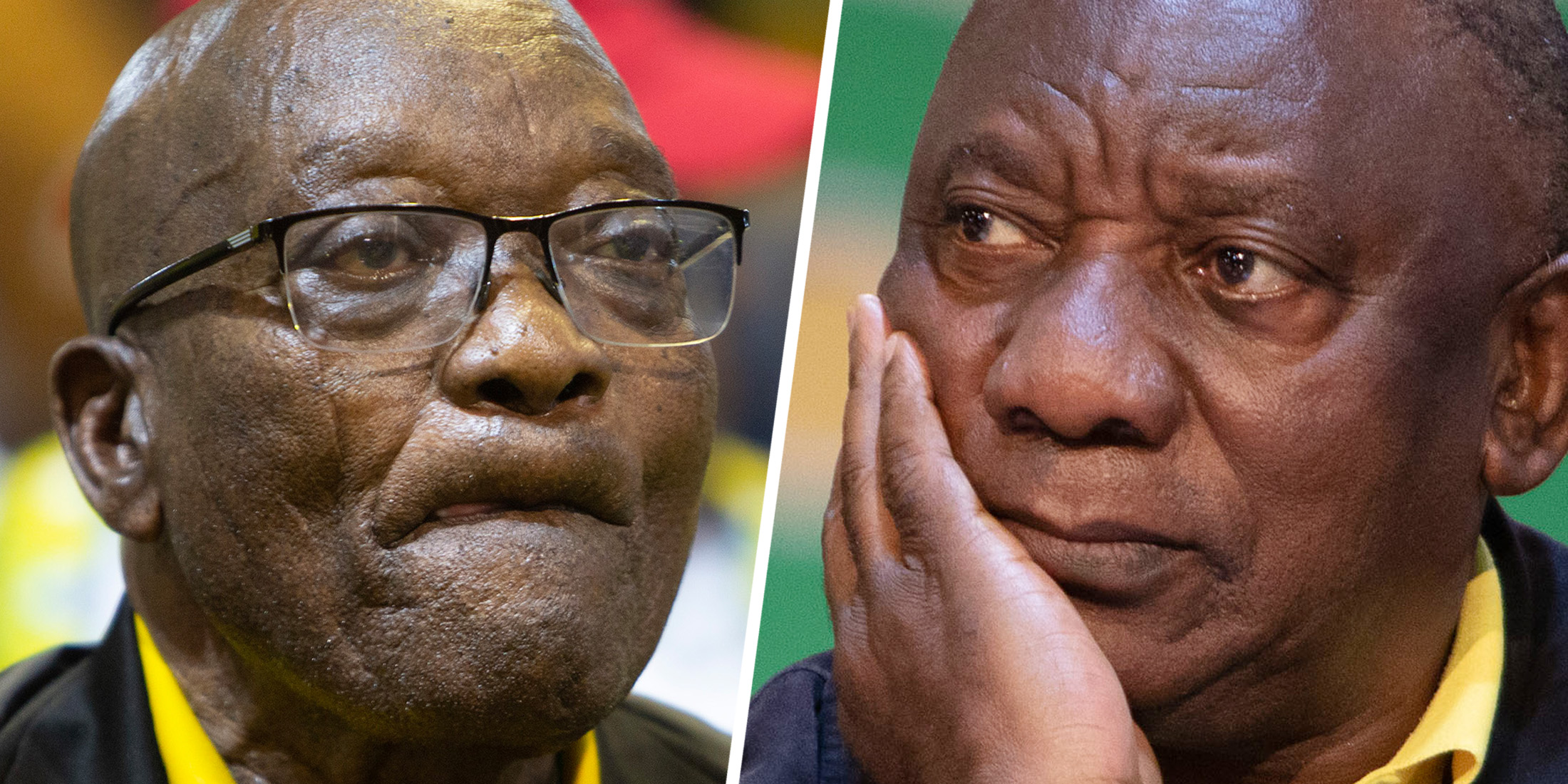

The constitutional court has confirmed the decision by President Cyril Ramaphosa not to appoint two provincial directors of public prosecutions selected by former president Jacob Zuma in the final days of his presidency.

Justice Steven Majiedt penned the 54-page majority judgment in the case which was agreed to by Justices Jody Kollapen, Rammaka Mathopo, Owen Rogers, and Leona Theron.

However, Judge Raymond Zondo has penned a dissenting judgment, saying Ramaphosa was wrong to have revoked the appointments.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Two Zuma-appointed provincial NPA bosses take the fight for their jobs to ConCourt

The final order is based on the majority judgment.

Ron Simphiwe Mncwabe and Khulekani Raymond Mathenjwa were both appointed in North West and Mpumalanga respectively a week before Zuma left office in February 2018, but the decision was never made public.

The two were informed of the appointments by former National Prosecuting Authority head, Shaun Abrahams, but the majority of the Concourt has ruled that Abrahams was not properly authorised to do so.

The case was brought by Mncwabe and Mathenjwa in two separate applications after Ramaphosa withdrew the appointments, alleging they were never formally communicated. Zuma had signed a presidential minute on the appointments which was shared with then Justice Minister Michael Masutha and Abrahams. Musutha countersigned the Presidential Minutes.

Abrahams then communicated the decision via phone and WhatsApp, but the Concourt has found this communication was not authorised.

Authorisation

Justice Majiedt dealt with the question of whether Abrahams was authorised to communicate the decision to Mncwabe and Mathenjwa, ultimately deciding that he was not.

He said Abrahams claimed he had “implied power” in his position and acted on that.

He said the appointment decision “lacked finality” until it was properly communicated “by or on behalf of the decision-maker”.

“Neither Mr Abrahams nor the applicants lay claim to an express instruction from president Zuma. There is also no evidence of any such express instruction. Express authorisation appears, to me, not to have come from the President or his office,” Justice Majiedt said.

He adds that there is insufficient evidence from Mncwabe and Mathenjwa to prove that Abrahams has “tacit authorisation” through an existing practice in the department.

“The applicants merely allege such a practice, but do not describe it in detail or adduce evidence as to its existence…Crucially, there is no evidence at all, not even any hint or suggestion, as to how the ‘Ministry’ came to be seized with the power from the decision-maker, president Zuma, to instruct Mr Abrahams to communicate the decision. For these reasons, I find that there was no such express or tacit instruction from president Zuma to Minister Masutha and by the latter to Mr Abrahams.”

Majiedt added that the signing of the Presidential Minutes was not sufficient to finalise the appointments and the affected parties had to be properly notified

“Even though the Presidential Minute is an indispensable step in the decision-making process, it does not on its own constitute a final decision,” he said.

Majiedt also notes that “there is a disturbing lack of evidence from both parties” which impacted the case.

“The applicants do not explain why they did not seek affidavits from former president Zuma and Minister Masutha. They were material witnesses for the applicants’ version of events, having played central roles. Only they could explain whether they had instructed Mr Abrahams to communicate the Presidential Minutes. Further, former president Zuma, who signed the Minutes, had a direct and substantial interest in his instructions being executed, since at the relevant time he was the sole depository of the statutory power to appoint DPPs,”

The court found that Ramaphosa also did not provide sufficient explanation on how Abrahams got the information on the appointments.

“Apart from the bare contention in President Ramaphosa’s written submissions that Mr Abrahams took an “unauthorised step”, there is only a denial that Mr Abrahams was instructed to communicate with the candidates. There is even less evidence regarding the allegation that the information at Mr Abrahams’ disposal was leaked. In summary, neither of the parties has made out a clear case. This Court does not know what exactly transpired,” Majiedt said.

Dissenting judgment

Zondo and two other justices, Mbuyiseli Madlanga and acting justice Tati Makgoka, have disagreed with the majority, saying Ramaphosa was not entitled to revoke the appointments.

“In my view, the (Ramaphosa) was not entitled to revoke or withdraw the applicants’ appointments,” Zondo wrote.

Zondo said there were certain aspects of the factual background that the majority judgment did not cover and “in my view, are important for the proper determination of these matters”. He noted that prior to the appointments Mncwabe and Mathenjwa’s names were submitted to Zuma along with several others.

“In making the appointments president Zuma would have satisfied himself that each one of the applicants satisfied all the statutory requirements for appointment as Director of Public Prosecutions including having integrity, being a fit and proper person, having the right to practise in all the courts and having the requisite experience,” Zondo said.

He added that it is material that Masuthu had counter-signed the Presidential Minutes in which the appointments were contained before they were handed to Abrahams.

“Upon his return to Gauteng, Mr Abrahams immediately informed all the individuals who had been appointed by president Zuma that they had been appointed to the respective positions to which they had been appointed. Before the individuals concerned could assume duty in their new positions, they were informed that they had to wait for an announcement of their appointments by president Zuma. However, president Zuma resigned as President of the country on 14 February 2018 before he could make the announcements,” Zondo said. When Ramaphosa took office he asked Abrahams whether the appointments were “fast tracked’ as a result of Zuma leaving office. Abrahams denied this.

Zondo notes that the appointees “were left in the dark for a whole year” about why they weren’t allowed to take office.

Zondo said that while the NPA Act confers power on the President to be the only person who appoints a Director of Public Prosecution, the act is silent on the issue of announcement.

“There is no legal requirement either in the Constitution or in the NPA Act that the President’s decision to appoint someone as a Director of Public Prosecutions should be announced publicly,” Zondo said.

Zondo also notes that Mncwabe and Mathanjwa’s appointments were made as part of a group of five similar decisions and all were handed to Abrahams and he communicated the outcomes to all the affected parties.

“If Mr Abrahams had effectively usurped president Zuma’s function or Minister Masutha’s function in informing the individuals concerned of president Zuma’s decisions to appoint them, Minister Masutha would have expressed disapproval of Mr Abrahams’ conduct. He would not have just kept quiet,’’ Zondo said.

Zondo adds that there is “overwhelming evidence that, once the President has signed a Presidential Minute containing a decision relating to the National Prosecuting Authority, the Presidency sends that Presidential Minute back to the line function Department for the implementation of the President’s decision by public announcement or appointment letter”.

“What happened in this case is simply that, after president Zuma had made these valid appointments, the President (Ramaphosa) sought to reverse them when there was no basis in law for those decisions to be reversed.”

Zondo adds that given Zuma’s previous abuse of power in the removal of Mxolisi Nxasana from office, Ramaphosa “was not unreasonable in seeking to satisfy himself that president Zuma had not made these appointments corruptly or for ulterior motives before he resigned from office”.

“However, establishing that could simply not have taken a whole year. A month, or, at the most, two months should have been enough to establish that. In terms of section 13(2) of the NPA Act, the President was obliged not to do anything that unduly delayed the filling of these two very important positions. The President has not advanced any justification for the year-long delay before he took the decision on the appointments. Decisions such as these should be made without any undue delay. It is not acceptable that there were these kinds of delays before such decisions were made,” Zondo said.

He added that if he was in the majority, he would have ordered that Mncwabe and Mathenjwa should assume their positions and ordered the President to pay for the legal costs in the matter.

As the final order is based on the majority judgment, Mncwabe and Mathenjwa will need to abide by that decision since the Concourt is the final court. The dissenting judgment is mainly used to explain why three of the judge disagreed with their colleagues and may be used for academic purposes. DM

Politics

Zuma-appointed provincial NPA heads lose challenges despite Chief Justice Zondo dissenting in their favour