Being taken to a 5 o’clock show on a Saturday afternoon was an outing. Dad put on a jacket and tie, Mum dressed up in twinset and pearls and, if memory serves me well, my sister and I had nothing smarter to wear than our school uniforms.

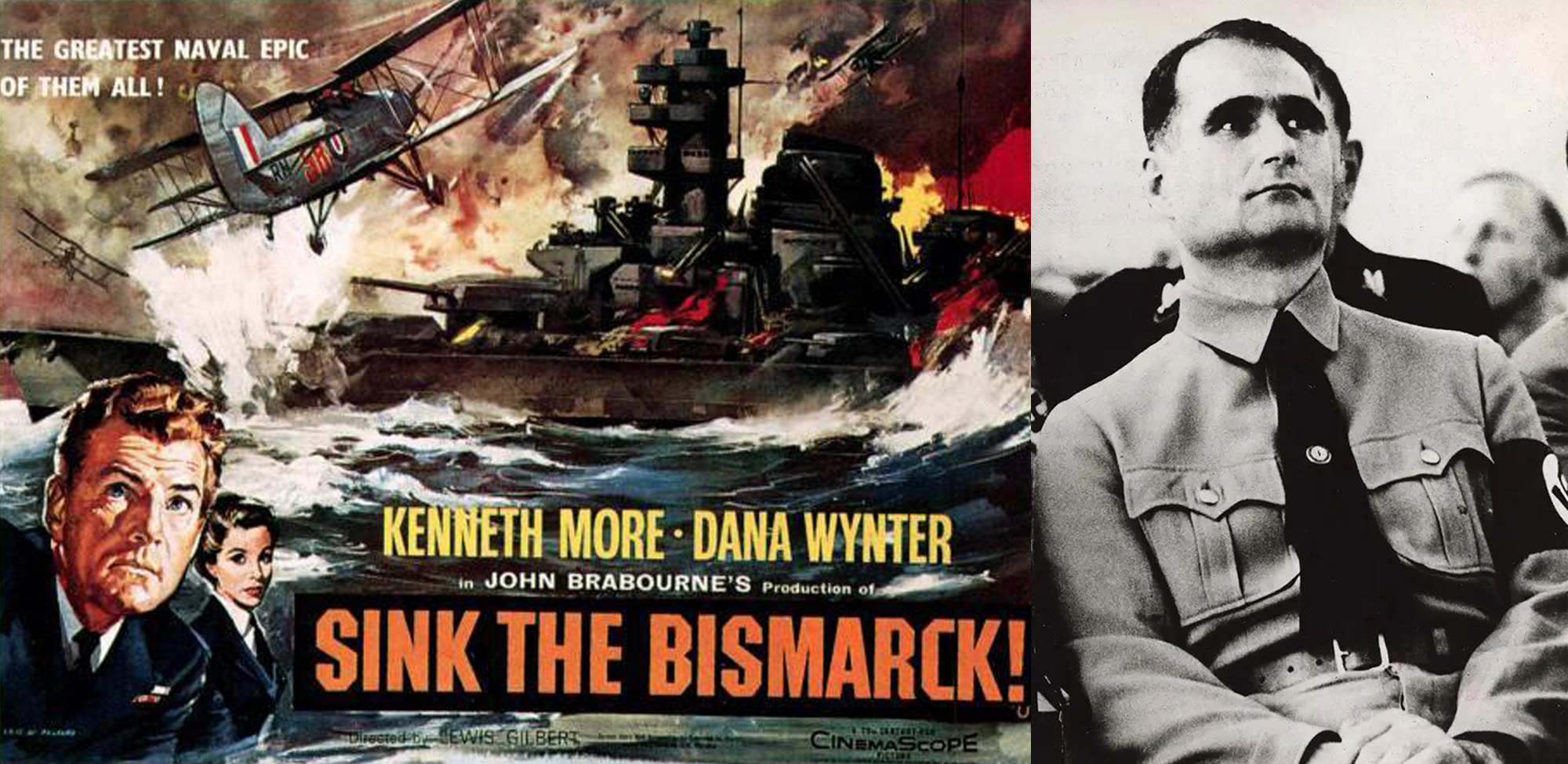

They obviously didn’t always choose films with me in mind or they’d have taken me to The Alamo – in which John Wayne played Davy Crockett – rather than Sink the Bismarck!

Of course, Sink the Bismarck! had battleships, biplanes and torpedoes, but much of the film concerned English officers with upper-class accents gathered around a large table in the war room, staring with furrowed brows at models of battleships and debating how best to solve the conundrum of the film’s title. British grit and stiff upper lips ultimately prevailed and the unsinkable Bismarck was sent to its watery grave – but not before it had challenged the received wisdom that Britannia ruled the waves.

As terrifying as the sinking of the HMS Hood was, the scariest part of the movie was the beginning – with swastikas flapping in the wind to the accompaniment of guttural German newsreel narration, Adolf Hitler saluting like a police pointsman directing the traffic and everyone chanting “Sieg Heil” as the Bismarck was launched on her maiden voyage.

This was the stuff of nightmares and, as a 10-year-old, I started having nightmares about Hitler and the Nazis.

That was the first time I’d seen the Führer on film. The only Germans featured in the British war comics I read were ugly, dim-witted soldiers with comical names like Wolfgang and Fritz, who were invariably knocked out cold with a single roundhouse punch delivered by a dashing British commando with a chiselled jaw.

Hitler wasn’t only ugly; he was evil. That’s why Mum and Dad joined the army to fight him.

Adolf Hitler with Rudolf Hess on his left. (Photo: Supplied)

Adolf Hitler with Rudolf Hess on his left. (Photo: Supplied)

At the time I didn’t know that many South Africans hadn’t wanted to fight Hitler. Later I discovered that some of them – mostly Nats – were Nazi sympathisers and if Jan Smuts hadn’t locked them up in internment camps, they’d have fought to make South Africa part of the Third Reich.

The Nats had a lot in common with their Nazi masters: autocratic intolerance, brutal militarism, a flagrant disregard for human rights and a fanatical belief in their racial superiority. As I got older, I came to see Hendrik Verwoerd and particularly the baleful BJ Vorster – a former inmate of the Koffiefontein internment camp – as every bit as sinister as Hitler.

The ideological parallels between the Nazis and the Nats heightened my interest in the history of World War 2 and the Third Reich.

***

By the early 1970s, I was a drama student at Rhodes University.

Nothing in the preceding decade would have pointed to this as an obvious career choice, but a secular Damascene moment while watching a production of Shakespeare’s Henry V changed all that.

I was simultaneously stagestruck and out of my depth. One way of catching up with my peers was to see, read and listen to as many plays as I could.

In the city library I found an LP of a play by Peter Weiss called The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, which read more like a movie logline than a snappy title. No wonder everyone referred to the play as Marat/Sade. I played the record so many times I knew it off by heart.

I was eager to read more by Weiss and ordered his documentary play The Investigation.

I discovered it was a dramatic retelling of the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials. Weiss selected and edited testimony given over a period of 18 months in what he subtitled an Oratorio in 11 Cantos. It was profoundly shocking and I was impressed by the power of documentary theatre.

By the end of my third year, I’d abandoned all hope of a glittering career as a dashing leading man. In my final year, I directed Jean Genet’s The Maids during the Arts and Science Week, and the encouragement I received from staff and students alike emboldened me to settle on directing as a new career path.

The following year, I escaped South Africa’s politics and parochialism and secured a place on the director’s course at the Old Vic Theatre School in Bristol.

During the interregnum between my acceptance at theatre school and the commencement of the course, I immersed myself in London theatre. I was mostly interested in modern plays and new writing. Writers – particularly playwrights – were my new heroes. In 1973 I sporadically kept a diary, and on 21 July I made the following entry:

“Have been in London for just over three months. During this time I have seen over 60 productions… Among the best new plays that I have seen are: Savages by Hampton, Bond’s The Sea, Magnificence by Brenton, Ionesco’s MacBett and The Removalists by David Williamson.”

But it was Howard Brenton’s play that made the deepest impression. It begins with a group of activists squatting in an abandoned house and ends with a disaffected member of this group bent on assassinating a Tory government minister. A besuited establishment figure with sticks of gelignite wrapped around his head was an arresting theatrical image – and the play ends violently, unlike so many British plays in which the dramatic question was routinely resolved with a clever quip.

Howard Brenton on the back cover of Magnificence, 1973. (Photo: Snoo Wilson / Author Supplied)

Howard Brenton on the back cover of Magnificence, 1973. (Photo: Snoo Wilson / Author Supplied)

After seeing this play I followed Brenton’s career closely, and if I couldn’t get to London to see a play of his, I’d read it.

So it came as no surprise when, in 1980, The Romans in Britain was singled out for prosecution by the morality campaigner Mary Whitehouse.

The politics of the play draws parallels between the Romans’ invasion of Britain and Britain’s invasion of Northern Ireland. But Mrs Whitehouse focused on a scene in which Roman soldiers raped a druid and, as theatre censorship had been abolished in 1968, was set on prosecuting the director under the Sexual Offences Act of 1956.

This law was intended to discourage men from soliciting for sex in public conveniences, which explains why a member of the defence team remarked that the prosecution viewed the National Theatre as little better than a public lavatory. Fortunately, the prosecution did not succeed.

***

As the director’s course in Bristol was only a year and I had funds to study for two, I started looking around for something to do in my second year. I knew a South African student who was doing an MA on Fugard’s plays at Leeds University and – prompted more by desperation than desire – I applied to do a master’s, although I have absolutely no recollection of my proposed topic.

The professor sensed my ambivalence towards academia and astutely suggested an International Postgraduate Theatre Studies Diploma started by Geoffrey Axworthy at the University of Cardiff’s recently opened Sherman Theatre. It was a practical course – which was more suited to my needs – so I sent off an application.

On Sunday, 5 May 1974, as usual, I bought the Observer. As I paged through the paper, I came across a review of a new book titled The Loneliest Man in the World.

I could have been forgiven for thinking it was about me, because that’s how I’d been feeling ever since a girlfriend in London had broken my heart the year before.

But it wasn’t – it was about Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s deputy Führer. The man who – if you examine the footage closely – you can see standing a few metres behind Hitler when the Bismarck was launched.

The Loneliest Man in the World book cover. (Photo: Author Supplied)

The Loneliest Man in the World book cover. (Photo: Author Supplied)

Hess had been with Hitler in Munich at the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, had assisted in the writing of Mein Kampf during their subsequent incarceration and was given his elevated, if somewhat ceremonial, title when Hitler came to power.

Although Hess was a dyed-in-the-wool Nazi, there were high-ranking members of the party who thought he was off his rocker. Herman Göring didn’t mince his words and said he was mad, and even the Führer mocked Hess for his dependence on astrology, telepathy and the supernatural.

Although he trained as a pilot before the end of World War 1, he saw no action. In 1929, he obtained his private pilot’s licence and, when World War 2 broke out, he asked Hitler to allow him to join the Luftwaffe. Hitler forbade him to fly for the duration of the war, but then relented and made the prohibition for one year only.

Exactly a year later, Hess started training in a Messerschmitt 110 reserved for his personal use. He requested several modifications to the aircraft, including long-range fuel tanks – he was a man with a plan.

Rudolf Hess and a Messerschmitt 110. (Photo: Supplied)

Rudolf Hess and a Messerschmitt 110. (Photo: Supplied)

As an insider, he must have known of Hitler’s intention to flout the non-aggression pact Nazi Germany had signed with Soviet Russia days before invading Poland. Hess quite reasonably thought it was a bad idea to conduct a war on two fronts and, without consulting the Führer, decided to contact the Duke of Hamilton as he’d been led to believe he opposed the war with Germany. His mentor Karl Haushofer convinced Hess that it wouldn’t take much to persuade King George VI to fire Churchill and pack him off to Canada.

On 10 May 1941, he took off from Augsburg, flew over the Frisian Islands, across the North Sea at low altitude to avoid radar, maintained his high speed and tree-top height over the English and Scottish countryside to elude Spitfires that had been sent up to intercept him, and eventually parachuted out of his plane 19km short of Dungavel House, the Duke of Hamilton’s residence.

At midnight, a startled ploughman came across him struggling with his parachute. Hess gave a false name and said he was there with an important message for the Duke of Hamilton. Even to this proverbially phlegmatic Scotsman, it must have been rather like encountering an extraterrestrial who’d stepped out of his spaceship and said: “Earthling, take me to your leader.”

WW2 Wreckage of Rudolf Hess Messerschmitt ME110 which crashed in Scotland. (Photo: Getty)

WW2 Wreckage of Rudolf Hess Messerschmitt ME110 which crashed in Scotland. (Photo: Getty)

After being handed over to the authorities, Hess explained he’d come to broker peace between Britain and Germany. This was the deal: if Britain would allow Germany to rule in Europe, Germany would guarantee Britain’s sovereignty over her empire. Hess later told Albert Speer – Hitler’s chief architect and, at the time, also incarcerated in Spandau – that “the idea had been inspired in him in a dream by supernatural forces”.

But the Duke of Hamilton didn’t want to make peace with Germany, the King didn’t fire Churchill and pack him off to Canada, Hitler spiralled into a Wagnerian rage and gave orders for Hess to be shot on sight. When the British locked him up, did Hess ever wonder how those supernatural forces could have so misinformed him?

The author of The Loneliest Man in the World was Eugene Bird, an American lieutenant-colonel who, for a time, had been the commandant of Spandau Prison.

He’d been relieved of his duties in 1971, when his superiors discovered he was collaborating with Hess – by then the sole remaining inmate in a prison built to accommodate 600 – on what was to become this book.

Towards the end of his review, Malcolm Muggeridge asks himself whether Colonel Bird had thought of writing a film or TV script. “Anyway,” he wrote, “he has written one – the lonely man in the big, empty prison; the ghost of Hitler’s Third Reich, with, all about him, the Kafkaesque stamping of feet, shouting out of words of command, maintenance of protocol, and other intimations of the presence of the Third Reich’s destroyers.” This paragraph obviously planted a seed in my overactive imagination.

During my interview with Geoffrey, I discovered we were expected to come up with ideas for our own projects, after which we would be given the creative environment and a theatre in which to develop and stage them.

Did I have any thoughts along those lines? Yes, I said, I’d like to write a documentary play about Rudolf Hess.

I must’ve been convincing because my proposal was accepted and I was given a place on the course. Then I was told the theatre had employed a writer in residence to assist us with our projects. For that year they’d engaged the services of – Adrian Mitchell! He was not only a famous poet, but he’d also done the English translations of the songs in Brook’s production of Marat/Sade. I couldn’t believe my luck.

***

It did occur to me that it would have been presumptuous to write about such German subject matter without ever having been there or seen where Hess was incarcerated.

A visit to Germany had been on my bucket list since a student in Bristol introduced me to Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weil’s The Threepenny Opera, which conjured up a nostalgic yearning for the extraordinary creativity of the Weimar Republic before the Nazis reduced it to a cultural desert.

My allowance – bankrolled by my generous grandparents – stretched to beer and cigarettes, not foreign travel. Then it occurred to me that I was going to be homeless – i.e. staying with friends – over the summer, so I’d be saving the money I’d otherwise have spent on rent. My birthday was coming up and I persuaded Mum and Dad that a modest injection of capital would be helpful for what was, after all, essential research for my play.

I’d also met Jörn van Dyck, a theatre director from Munich, who was translating Fugard’s Statements After an Arrest under the Immorality Act, and he’d extended an open invitation to stay with them.

Hubert, a German friend of a South African friend studying in Brighton, also offered hospitality and gave me the names of hospitable friends of his dotted around the country.

I borrowed a sleeping bag and a rucksack, joined the International Youth Hostel Association and – as I wanted to see a production by Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble and South African passports were not valid for East Germany “unless otherwise endorsed” – I presented myself at the Consulate General to apply for the requisite endorsement. That would give me access to the communist world but if I was detained by the Stasi, said the consular official narrowing her eyes, I was on my own – there was nothing my country could do for me.

Endorsement for East Germany. (Photo: Author Supplied)

Endorsement for East Germany. (Photo: Author Supplied)

I travelled to Antwerp on a great student discount, then caught another train to Amsterdam where I’d arranged to meet up with David de Beer.

He’d had banning orders served on him in South Africa and had recently left the country on a one-way exit permit. He was staying with BBC journalist Mike Popham, who said I was also welcome to stay if I didn’t mind sleeping on the floor.

We turned on the TV, drank excellent Dutch beer and celebrated as we watched Nixon delivering his resignation speech. I fell in love with Amsterdam but couldn’t have guessed I’d be back the following year and that it would be my hometown for the next two decades.

On my 25th birthday, predictably hungover, I caught a train to Arnhem and began hitching to Berlin with a copy of Eugene Jackson’s German Made Simple, a budget of £4 a day and a travel journal – in which I noted with my propensity for self-dramatisation: “As usual, a lonely birthday.”

Student card 1975. (Photo: Author Supplied)

Student card 1975. (Photo: Author Supplied)

It took me two days to reach Berlin, the last stretch along a corridor of Reichsautobahn through East Germany that hadn’t been upgraded since Hitler launched the Bismarck.

Hubert’s friend Peter Geiss wasn’t at home, so I checked into a hotel at double my daily budget. Peter phoned later and offered me a place to stay. I think he may have even succeeded in cancelling my hotel booking. In my journal I noted that I found “a tremendous amount of warmth & generosity in the Germans” and in the streets people greeted you with “Wilkommen in Berlin”.

I shuddered inwardly at Checkpoint Charlie as I presented my endorsed passport to the unsmiling East German border guards, crossed into the Communist World in an infernal heatwave, discovered the Berliner Ensemble was closed for the holidays, smoked a Texan “in contemplative silence” on the Bertolt-Brecht-Platz, wandered towards the Brandenburg Gate not far from where the Red Army had destroyed the bunker where Hitler and Eva Braun had committed suicide, noted that there were police on the pavements at 50-metre intervals, took off my shoes and, while I cooled off my feet in the fountain on the Marx-Engels-Platz, made the following entry in my travel journal:

“There is certainly an air of deprivation & proletarian drabness – all the people in uniform who are dead behind their eyes – & this seems a strange paradox given the ostensible commitment to culture – in the theatre, opera & ballet.”

From Berlin I hitched a ride with a Greek truck driver, who spoke no English or German.

The trip took 12 hours, we didn’t stop to buy food and he never offered me one of the sandwiches he ate at regular intervals. But in Munich I was royally entertained, was taken to places off the tourist track, discussed the Fugard translation with Jörn, went to museums with his wife Sine – a History of Art graduate – and, on a cold, wet afternoon, caught a bus to the concentration camp at Dachau, which is a salutary reminder of the obscene inhumanity of authoritarian regimes.

A week later I met Hubert in Düsseldorf and cadged a lift back to Brighton.

But I hadn’t forgotten Rudolf Hess.

Soviet troops guarding Spandau.(Photo: Author Supplied)

Soviet troops guarding Spandau.(Photo: Author Supplied)

I stood alone facing the grim façade of the prison housing the loneliest man in the world.

Of course, the real reason the deluded and deranged Hess had to stay in Spandau was because it was guarded by the four post-war Allied powers on a rotational basis, and the Russians were adamant that a life sentence for Hess meant exactly that.

There is a view that keeping Hess in Spandau gave the Soviets access to West Berlin, and when they guarded the prison it was a centre for Soviet espionage operations. I recorded my impressions in my journal.

Travel Journal, 17 August 1974. (Photo: Author Supplied)

Travel Journal, 17 August 1974. (Photo: Author Supplied)

I decided something of a theatrical intervention was necessary.

“After taking in my initial impression, I lit a cigarette & attuned my mood for my first casual and momentous walk up to the gates of Spandau. I went within about 10 metres from the main gate and spent about 3 to 4 minutes smoking and observing. Then the door opened & a black guard emerged & sauntered up to me. I knew that I’d be told to go, but I was curious to hear what he had to say. It was a ‘Hey, man, you gotta get back on the sidewalk.’ He was pleasant enough about it but mentioned that the guards had orders to shoot! Like f**k, they would have shot me! I’m glad that there was at least that much of an incident. Now I’ve had contact with Spandau and that’s the closest I’ll ever get to Rudolf Hess physically.”

Looking at photos while writing this, I noticed a sign I don’t remember seeing at the time.

It was near the gate and stated that if you approached the fence, the guards had orders to shoot. So the GI was not kidding. Things might have gone very differently had the Soviets been on duty on 17 August 1974.

There’d have been a staccato burst of fire from an AK-47; a contorted body sprawled in front of the prison gate; President Gerald Ford was speechless, but that’s because he famously could only do one thing at a time and he was walking when he heard the news; Pravda – the official organ of the Communist Party – reported on how guards had foiled a brazen attempt to free Hess by a white South African with known links to neo-Nazi groupings in his fascist and racist homeland; South Africa House was tight-lipped when asked about the endorsement they’d given the suspect to enable espionage activities in communist East Berlin and in Cape Town, BJ Vorster asked Parliament to observe a minute’s silence for a fallen martyr in the heroic struggle against communist tyranny.

At 25, I’d have become a tragic-comic footnote in the annals of the Cold War.

***

I have no written notes on how I planned to proceed with my documentary play.

What part of the story did I want to tell? How many characters would I need to tell the story? How did I want to change the way people thought about Hess? I have absolutely no idea.

In his review, Muggeridge wondered whether Bird had considered writing a film or TV script. Perhaps the subject was too unwieldy for a stage play. Or had I started thinking along the lines of a two-hander, with the deluded Hess telling Bird about his mission to bring about peace? But then that would have been a narrative – not a play.

This was September and I’d have had to have the play written and staged within six or seven months. I already knew that Harold Pinter – another playwright hero of mine whose one-act plays I’d directed at theatre school in Bristol – said it took him a year to write a new full-length play. And he wrote three drafts! What was I thinking? Did I think a documentary play was easier because I wouldn’t have to invent the characters or the story? That’s how much I knew.

I don’t recall our writer-in-residence being much help either. As he was poet laureate of left-wing causes, he probably thought it risky to be associated with what a white South African who was – at best – liberal might want to say about the seemingly unrepentant, if mad, former deputy Führer of the Third Reich.

Of course, it didn’t help matters that Adrian had given up smoking at the beginning of term and everyone on the course went through his withdrawal symptoms.

I don’t know when I conceded I was punching above my weight, but not long after I got to Cardiff, Geoffrey asked me to direct a new play set during World War 1. It had been written by the local theatre critic for the Guardian newspaper and had the rather prosaic title Aspects of War.

When I agreed to do it, I knew I’d reneged on my commitment to Hess. Cardiff Little Theatre was one of the many amateur companies that was well supported in the UK. I enjoyed the challenge and realised there was something I could bring to the production. None of them had been in the army – I had.

Eight years later, I felt ready to write my first play and, as it happens, it was set in the army and it took me more than a year to write. I’d forgotten that directing that play in Cardiff may have been a stepping stone towards Somewhere on the Border. I wasn’t quite sure if I could call myself a playwright after only having written one play, but if anyone referred to me as such I didn’t contradict them.

Somewhere on the Border play text, Amsterdam 1983.(Photo: Author Supplied)

Somewhere on the Border play text, Amsterdam 1983.(Photo: Author Supplied)

Rudolf Hess in the summerhouse where he died on 17 August 1987. (Photo: H. Aldridge & Sons /BNPS / Supplied)

Rudolf Hess in the summerhouse where he died on 17 August 1987. (Photo: H. Aldridge & Sons /BNPS / Supplied)

Hess was still in Spandau. I didn’t think about him much, although I’d occasionally notice The Loneliest Man in the World looking reproachful and forlorn on my bookshelf.

Fast forward a few years, and I was working part-time as a literary manager for RO Theater in Rotterdam. Part of my job was assisting the artistic directors in putting together the season of plays.

I don’t recall whether it was my suggestion, but we included the winner of the 1985 London Evening Standard Best Play Award in the repertoire. The play was called Pravda.

The towering villain of this “Fleet Street comedy” was a South African press baron named Lambert le Roux – performed magnificently, but with the most idiosyncratic South African accent, by Anthony Hopkins.

As it was a given in liberal democracies that white South Africans were monsters, Le Roux was the perfect stand-in for Australian media tycoon Rupert Murdoch, whose acquisition of The Times and The Sunday Times posed a serious threat to editorial independence. The play was written by David Hare and Howard Brenton.

Both playwrights were invited to opening night.

Hare was unavailable, so Brenton came alone and I gladly assumed the role of being his minder. And that’s how we finally met 13 years after I’d seen Magnificence at the Royal Court. Howard – we were immediately on first-name terms – is a warm, generous and engaging person. He’d planned to spend the weekend and had booked into a hotel in Amsterdam, so after his obligatory meet-the-press engagements and attending opening night, we drove back together.

Howard had brought a bottle of champagne along to give to the director and, as the opportunity never arose, he suggested we buy 16 oysters and wash those down with the bubbly.

It was the first time I’d eaten oysters so, to return the favour, I acquainted him with the lurid charm of the bars in my neighbourhood – the red-light district – where, duly recorded in the daily journal I’d just started keeping: “we talked about theatre and love relationships” while surrounded by Thai girls, wearing little besides Oriental mystique, and topless barmaids serving drinks.

That weekend Howard re-established contact with Ritsaert ten Cate, the founder and artistic director of Amsterdam’s Mickery Theatre, a theatre that became synonymous with the international avant-garde.

There was a time when Mickery also sustained British fringe groups. That’s how Howard met him in 1970 and that’s where – developed during a workshop with actors – he began work on the play that would become Hitler Dances.

On Sunday afternoon, while waiting for his flight at Rotterdam Airport, we drank beer and quoted WB Yeats’s poetry to each other. Howard mentioned that Yeats had, for a time, supported fascism and Mussolini. That sobered us up, but not for long. When his flight was called, Howard picked up his bag and declaimed: “I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree…”

During their reunion, Ritsaert sounded Howard out about writing a new play for Mickery, and a year later he confirmed he’d accepted a commission and that he’d be coming to Amsterdam in February 1988 to start working on it.

A year later, he told me the Dutch playwright/director Lodewijk de Boer would be directing his new play called Hess Is Dead.

Rudolf Hess had died on 17 August 1987 and I must have seen coverage on television news and in the papers, but a lot of other stuff was going on in my life at the time and, anyway, I thought I’d moved on from Hess.

I had no idea how Howard had approached a subject that had defeated me as a callow student, but I was soon to find out.

In February 1989, he called from London and asked if I’d translate it into Dutch. I hesitated, but both Lodewijk – with whom I’d previously collaborated on a Sam Shepard translation – and Ritsaert wanted me to do the job.

Howard Brenton's inscription to the author. (Photo: Author supplied)

Howard Brenton's inscription to the author. (Photo: Author supplied)

Hess Is Dead is a multi-layered, multi-media dramatised investigation into events surrounding Hess’s death. Conspiracy theories had already been circulating before 1979, when a former British Army doctor who’d examined Hess published a book called The Murder of Rudolf Hess. (This doppelgänger theory – that Hess was not really Hess – was only conclusively disproved in 2018.)

Although he had attempted suicide on several occasions, his family claimed the frail 93-year-old could not have hanged himself and that the marks left on his neck by the electrical cord were consistent with strangulation. And there were reports of unknown men in US army uniform having been present at the scene.

True to Mickery’s avant-garde roots, the play was not staged in a theatre but in the Waag, one of the original city gates that later became a weighing house, then a guildhall.

The Guild of Surgeons had a room in the building where criminals who’d been hanged outside the city gates were brought in for anatomical dissection. This is where Rembrandt painted The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp and this is where Hess received his inevitably inconclusive theatrical postmortem.

The Waag is situated on Nieuwmarkt Square, 130 metres from the flat that was my home for 12 years.

Hess Is Dead opened on a freezing December night and, as I made my way to a bar after the show – not a topless bar, I hasten to add – I turned back to look at the monumental red-brick structure and, in the mist, found it hauntingly reminiscent of Spandau which, by then, had been demolished, pulverised and scattered in the North Sea to prevent it becoming a neo-Nazi shrine.

Howard Brenton and Anthony Akerman, London 2016. (Photo: Author supplied)

Howard Brenton and Anthony Akerman, London 2016. (Photo: Author supplied)

Although I never did write the play I’d intended to write, I was pleased that a playwright I admired had done so and that I’d played a part in the creative process. I felt I’d closed the circle and it had a satisfying symmetry which, I’m sure, would have appeared entirely self-evident to Hess with his beliefs in astrology and the occult.

I opened my desk drawer to put away the notebook I’d carried with me through Germany in August 1974.

As I flipped through the pages one last time, something caught my attention. It was a date – 17 August. It was the day I’d been to Spandau in 1974.

But there was something else familiar about that date. But what? Then I remembered.

It was the day Hess died – and I realised it had been 13 years to the day I’d been to Spandau. As I put away the notebook and closed my desk drawer, I wondered – only briefly – if this could also have been orchestrated by those supernatural forces Rudolf Hess so fervently believed in. DM

Anthony Akerman’s memoir Lucky Bastard is now available at Exclusive Books and most leading bookstores, also on Takealot, Amazon and Kindle. Reviewers are asked to direct all enquiries to ikesbooks@iafrica.com

Howard Brenton and Anthony Akerman, London 2016. (Photo: Author supplied)

Howard Brenton and Anthony Akerman, London 2016. (Photo: Author supplied)