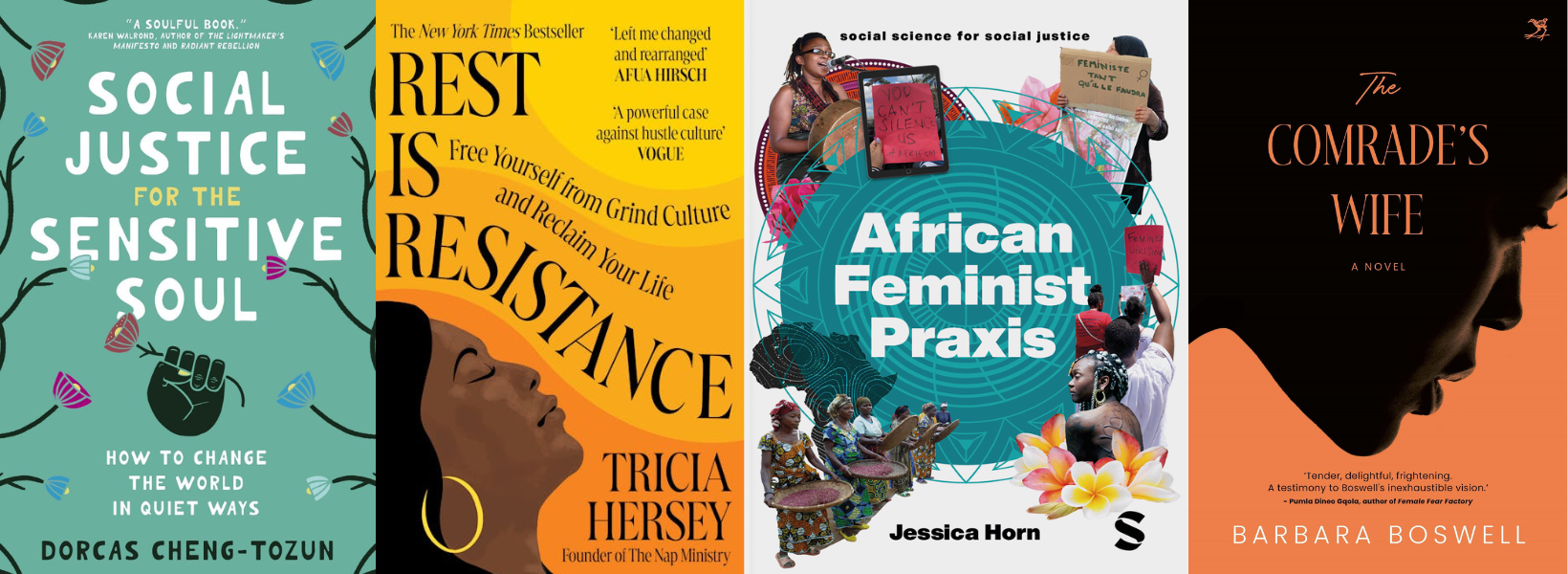

Today, having not had enough sleep yet again, because a book kept me up into the early hours, I felt inspired to share something about several phenomenal books that have kept me out of sleep over the past few months.

Barbara Boswell’s The Comrade’s Wife was both a plausible story and a relatable page-turner, despite wanting to shake awake the protagonist, to have her see how easily swayed she was by attention, material possessions and expensive gifts. As good page-turners do, I needed to know what would happen next. I wasn’t disappointed.

The visual nature of Boswell’s novel is cinematic, bringing each character, situation and context into clear perspective. I could see a film or binge-worthy Netflix series that would be a natural extension of the book. The last time I read a novel by a South African author that possessed this kind of cinematic scope was Damon Galgut’s The Promise, which won the Booker Prize, and was written shortly after he had completed a film script.

Social Justice for the Sensitive Soul: How to Change the World in Quiet Ways by Dorcas Cheng-Tozun felt like breathing out, deeply, as if I had been holding my breath for the longest time.

Our current world seems designed to benefit extroverts, and in my work with social change organisations, whether in civil society, policy institutes, philanthropies or UN agencies, I see how extroverts are rewarded, on a constant uphill career trajectory.

Cheng-Tozun’s carefully researched book recognises how the bias towards extroversion is embedded in cultures, practices and ideas about leadership, and what that looks and sounds like.

She understands how highly sensitive people, who are often also introverts, are overlooked when climbing the ladder of career progression.

In a hopeful manner, Cheng-Tozun identifies myriad social justice visionaries of modern times, who were also sensitives and introverts, and who made outsize contributions to changing our world for the better. She illustrates that working to create radical change in the world doesn’t require charisma, the gift of the gab or the ability to network and “know” all the right people and their circles.

We don’t need to make ourselves particularly visible to make significant contributions. We don’t need to loudly occupy space, be seen at every strategic forum, or ensure we know all the important people to succeed. We don’t need to continually draw attention to ourselves to change the world.

Her book reveals that sensitives who feel the world more intensely, and therefore are often drawn to social justice work, and introverts, who may lack charisma and avoid being the centre of attention, have made large contributions to social justice, leaving us with a better, more equitable world than they came into.

While I take my hat off to those with boundless energy, those constantly networking and those seeming to lead effortlessly, I also know that doing the work of social justice requires a great deal of energy and, for introverts and sensitives, significant recovery time. At the pace of our current world, there is rarely enough time for recovery before getting back in the saddle and galloping off to the next high-profile gathering.

A book that speaks to the exhaustion and endless grind we find ourselves in is Tricia Hersey’s bestseller, Rest is Resistance: A Manifesto.

Hersey, who gained global attention with her Nap Ministry, insists on rest as a form of resistance to capitalism, colonialism, patriarchy and related slavery and indenture.

She considers how many of us have ancestral heritages where those who came before us were denied rest because of the power dynamics of slavery, colonialism, indenture, apartheid, caste, class, racial and gendered discrimination.

Many of our ancestors were considered less human – more workhorses than people. This is a reminder of the crucial invisible work, the unacknowledged work done by those who continue to toil for little reward, working hard but living poor, struggling to put food on the table despite their relentless, effortful labour.

I’m thinking here of women farmworkers, women informal traders, domestic workers, garment workers and others in precarious employment whose work it is to cook, clean, serve, work the fields, raise children and keep house, who must go to work regardless of how poorly paid or backbreaking that work is, to sustain their families. And for those of us fortunate enough to have steady incomes or employable skills, we also do a great deal of juggling, putting in unpaid labour that is often gendered, but often doing so with the help of others, most often poor women.

Hersey reminds us that we carry ancestral pain. And we carry ancestral exhaustion.

Our sleep and rest deficits are sky-high. In Hersey’s hands, sleep and rest become political projects of reclamation. Hersey, who attended graduate school at a theological seminary, preaches rest and refusal, encouraging us to take the rest we deserve as acts of resistance to the grind of capitalism, and as an ancestral entitlement – a form of reparation. She makes a good case that could, however, prove challenging for the poorest – especially in contexts of high unemployment – doing what is perceived as manual and unskilled labour. The invisible work that feeds, clothes and cares for us.

Exhaustion sits deep in our bodies and psyches, and in addition to the pace of life and causes of exhaustion in our contemporary lives, it is carried over from one generation to the next. Do I need to sleep for my ancestors who lived in poverty, and who did not have the luxury of resting when they had to toil to feed and clothe their families? Is rest a form of reparation I am entitled to claim on behalf of my ancestors? Can I give myself rest as something my ancestors did not have the luxury of enjoying?

My ancestors, in many ways, had a much harder life than I do. Their toil was a given under both colonialism and apartheid, because children needed to be fed, clothed, shod and schooled. Ensuring their children received a decent education was imperative to ensuring they/we would have opportunities denied to their/our parents. I, and many of you reading, don’t live with the same pressures as our ancestors. We have the luxury of an education that has resulted in employable skills and a likely shift in class position. And I am exhausted.

Reading Hersey, I could not help thinking that those of us who can claim rest may have come from oppression, but we are not the ones living the most precarious lives now. The cost of asserting the right to rest differs depending on economic and class position. We don’t all have the same privilege to rest as much as we like or need.

I don’t think I’m unusual in living with compounded exhaustion. I know I have less energy than the “ordinary person” and I know why. My disability, following a freak accident, has meant living with chronic pain for more than 20 years. While it is managed, thanks to having the resources to do so, constant pain usurps a great deal of my energy. I’ve been managing this pain and its attendant exhaustion for more than two decades. In thinking about rest and Hersey’s ministering, I tried to think about whether my exhaustion started with my disabling injury. While exhaustion from pain slashed my available energies substantially, having to manage limited energies predated my injury.

While working at the UN Development Programme in the Nineties, I opted to live in cosmopolitan Johannesburg rather than in apartheid Pretoria, now Tshwane. The cities, a little more than an hour apart, added three hours of commuting to my workday. I know this is common for many workers, and that some have much longer, more convoluted commutes due to continued spatial apartheid that places the poorest at the outskirts of cities and towns.

The length of my commute and workday meant I could not indulge in social activities during the week, much to the consternation of friends who were then also in their twenties. They lived and worked in the same city, many were night owls, who could both party late and pitch up fresh and bright-eyed for work the next day. I couldn’t do that. I then remembered my frequent cases of “weekend flu”. I went through long stretches of ongoing weekend flu during this period in my working life. It worked like this: I would get sick on Fridays after work, be ill all weekend, and then return to work on Monday morning. Looking back, my body was demanding rest whenever it could – at the weekend – only to ensure I could function again for the work week. I wasn’t toiling in fields or down mines. I wasn’t raising children or cleaning someone else’s house. I wasn’t raising someone else’s children in addition to my own. I wasn’t earning a salary that committed me to a life of economic struggle, and my work was relatively sedentary. But I was exhausted.

Returning to books that have kept me up late: Jessica Horn’s recently published, phenomenal African Feminist Praxis: Cartographies of Liberatory Worldmaking has had me cramming in a couple more revelatory chapters each night. I concur with African feminist academic intellectual Pumla Dineo-Gqola’s view that it is a meticulous offering. I am amazed at the encyclopaedic nature of Horn’s labour of love, which illustrates both an exceptionally conscientious archivist and a finely gifted cartographer who maps a vast yet detailed contemporary history of African feminism as a communal, freedom-seeking, liberatory project.

I continue to lose sleep as I make my way through her remarkable survey of African feminist praxis – rooted in freedom-seeking resistance, defiance, refusal, subversion and courage – to achieve liberation from oppression for all who self-identify as women, girls and non-binary people across our continent, regardless of who the oppressors are, and despite the highest odds. DM

Sarita Ranchod is a South African writer, researcher and sculptor who explores freedom and power through a feminist and decolonial lens.

Maverick Life

Lost in the pages — the books that steal my sleep and capture my soul

Reading is profoundly personal, a solitary indulgence I deeply cherish. Most of my reading unfolds quietly in bed, a private literary adventure rarely shared despite being a lifelong, voracious reader. It’s mine, and intimately so.