Biopics are a particularly interesting genre in cinema, as they often reveal something as meaningful about the filmmaker as they do about their subject. Raging Bull, one of the greatest of all films, is as scourging a view of Martin Scorsese himself, as it was of the boxer Jake LaMotta. And in Marie Antoinette, Sofia Coppola depicts her own inner world, under the guise of a portrait of the French queen.

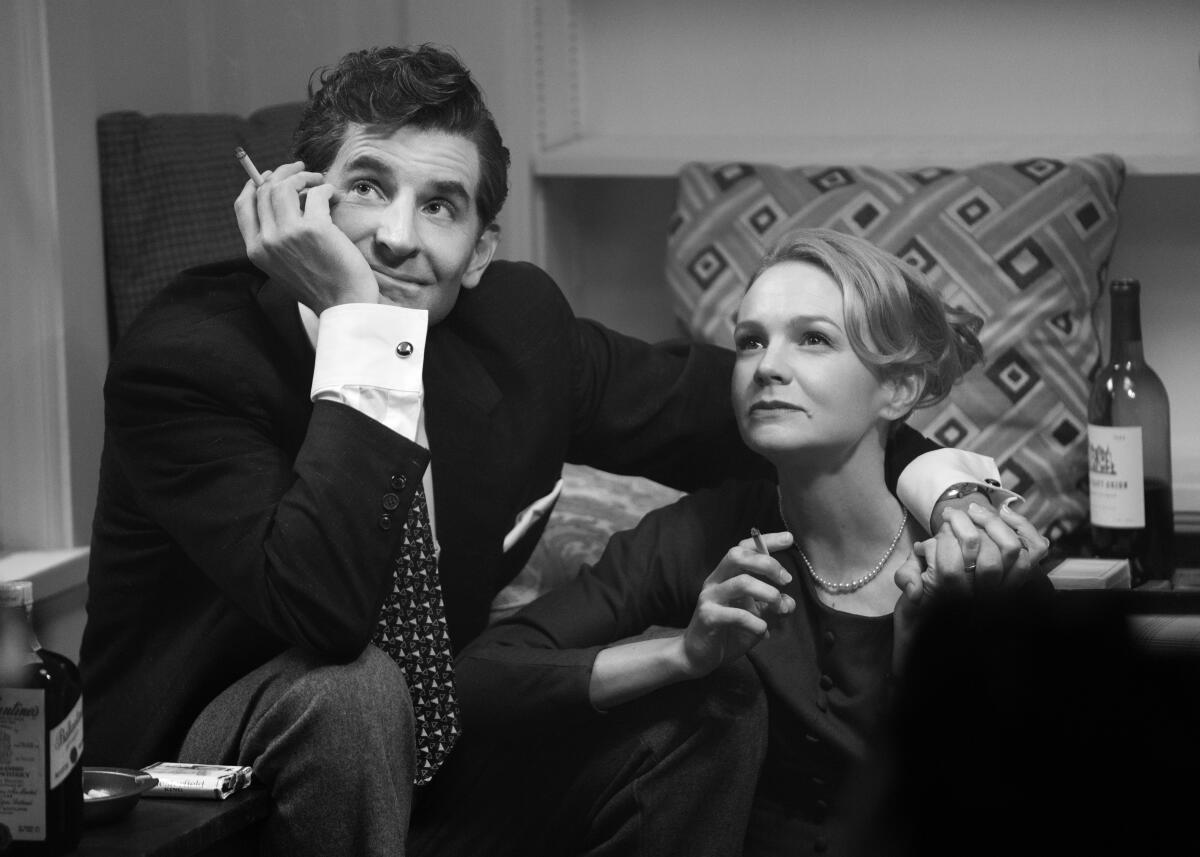

Maestro, the new biopic on Leonard Bernstein and his wife, Felicia Montealegre, is just as much about the ambition of Bradley Cooper (who co-wrote, directed and starred in the film) as it is about Bernstein’s life and artistry. The story centres on the marriage between the characters of Lenny – the great American composer-slash-conductor-slash-pianist-slash-educator-slash-irrepressible-bonanza-of-sound-and-cigarette-smoke – and Felicia (played by Carey Mulligan), a Costa Rican actress who starred on Broadway and television. And it’s a great show of an actorly and director-ish ostentation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gJP2QblqLA0

Cooper and co-writer Josh Singer focus on the tensions in the marriage brought about by Lenny’s extramarital indiscretions (apparently only with men), Felicia’s truncation of her career to manage her husband’s domestic affairs and buffer his public image, and, finally, her illness. The core marital conflicts are so common as to be generic, and the aspects that make Felicia and her experiences special (as they indeed were, in real life) are hardly conceived in this film.

I was surprised – and disappointed – to find that Maestro elides more than an entire decade, by jumping from the mid-1950s to the early 70s, and skipping Bernstein’s directorship of the New York Philharmonic (as well as the Broadway run and film version of West Side Story). This was a critical time in Montealegre’s public life as well: on 14, January 1970, she threw a fundraiser for the Black Panther Party, which, among other things, gave rise to the snide term “radical chic”.

By ignoring so much, Cooper excludes enormous parts of who Montealegre was and what she did: her strong political positions, her worldview, her decisive actions, her public perception, her fullness as a bright and famous being. Maestro seems to narrow Felicia to simplistic, blaring talking points, and the deeper elements of her emotional life are only partly expressed in a scene of a heated argument, where most of it is not heard as Lenny talks over her, and it’s wrapped up in the contrived pathos of a Snoopy float.

Soul divided

Bradley Cooper reportedly spent six years learning to conduct, so that he could render the conclusion of Mahler’s Second Symphony live. (Image: Netflix)

Bradley Cooper reportedly spent six years learning to conduct, so that he could render the conclusion of Mahler’s Second Symphony live. (Image: Netflix)

As for Lenny himself, Maestro paints an unambiguous and uninflected portrait of him as a soul divided; he’s conflicted between the rhapsodically public life of an exuberant performer and the solitary and private life required by a composer to plumb his expansive inner world – a world in which anguished secrecy is imposed by a homophobic culture.

Yet, for these thinly conceived characters, Cooper and Mulligan give highly technically accomplished performances. Cooper throws himself fully into impersonating the more famous Bernstein’s voice (both young and old) and his kaleidoscope of cigarette-wielding techniques. Mulligan, a gifted actor, is restricted here to a small range of vocal idiosyncrasies and conspicuously pained facial expressions.

Oscar fodder

The official poster for Maestro. (Image: Netflix)

The official poster for Maestro. (Image: Netflix)

Reports of Cooper spending six years learning to conduct so that he could render the conclusion of Mahler’s Second Symphony live, is pure Oscar fodder, like Leonardo DiCaprio eating a raw liver in The Revenant, or Matthew McConaughey losing 50 pounds for Dallas Buyers Club. It’s ostentatious hard work, which is impressive to the professional actors in awards-show voting bodies, but it doesn’t evoke the long-lived-in body and soul that Bernstein radiated every second of his life.

One unalloyed pleasure offered by Maestro is its music.

Cooper’s wisest choice was to compile a soundtrack from Bernstein’s compositions, mostly in new recordings of the London Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of Yannick Nézet-Séguin, and released as a soundtrack album by Deutsche Grammophon. (A delightful easter egg for fellow opera lovers is the fleeting onscreen appearance of Isabel Leonard, in the recreation of the Mahler performance at Ely Cathedral.)

I listened to the album immediately after seeing the movie; the music was such a whirl of colour and wit, of snap and swing, of verve and far-flung passion, that Maestro’s failures seemed all the more grievous. DM

'Maestro'. Image: Netflix / Supplied

'Maestro'. Image: Netflix / Supplied