South Africans are mourning the death of playwright Athol Fugard who died today, 5 March, 2025. Anthony Akerman wrote this living tribute to Fugard on the occassion of his 90th birthday. We republish it today as reflection of a life that inspired many.

In 1968, partially brain-dead after nine months in the army, I enrolled for a BA degree at the Pietermaritzburg campus of the University of Natal. I had no idea what I was going to do with my life, but took Psychology because I’d told my dad I might go into advertising.

In res, I became friends with Mark Stannard and spent part of the July vac at his dad’s place in Munster near Port Edward, where he taught me to water-ski on the Mtamvuna River. Mark wasn’t averse to name-dropping and, no doubt trying to impress me, said, “My mother’s friends with Athol Fugard’s wife.” I stared at him blankly. “Who?”

“He’s a playwright,” said Mark, “and they live in Schoenmakerskop near PE. They’re so poor they can’t afford a fridge.”

Playwriting didn’t sound like such a great career choice. The only other playwright I’d heard of was William Shakespeare and he’d definitely never had a fridge.

Later that year, I went to see a Shakespeare play at the University Theatre, Howard College, in Durban. I only did so because the play – Henry V – was an English set work and I thought if I saw it I wouldn’t have to read all those impenetrable iambic pentameters. When the Chorus stepped out on the stage and spoke the first lines, I suddenly knew what I wanted to do with the rest of my life – and it wasn’t coming up with catchy slogans to sell peanut butter.

Someone should have told me acting was as precarious a profession as playwriting, but my parents didn’t know anything about either profession. However, my dad did insist that I finish my degree so I’d have something to fall back on. I told him I wanted to switch to Rhodes University because I’d been told they had the best English Department in the country.

The real reason was that if I got out of Natal, I wouldn’t have to do monthly parades with my citizen force unit, the Natal Field Artillery. I decided to major in Speech and Drama and encountered some really boring playwrights.

I had a walk-on part in a play by the Roman playwright Plautus. He was supposedly one of the world’s first comic playwrights, but the only joke in his repertoire was having two people look identical. The audience wasn’t exactly rolling in the aisles.

After reading a medieval morality play called Everyman by a guy called Anonymous, I started to wonder if advertising wouldn’t have been a better career choice after all.

Then, just before returning to Rhodes to start second year, I heard about another play at the University Theatre. It was Boesman and Lena and had been written by Mark Stannard’s mother’s friend’s husband. I’d occasionally heard his name mentioned at Rhodes because he was friends with one of my English lecturers, Don Maclennan. Apparently, Don and Athol Fugard used to fish together while discussing Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. I had no idea what to expect, but it couldn’t possibly be more boring than a medieval morality play.

I took my seat in the auditorium, feeling more at home than I had two years previously when I entered this theatre to see Henry V. The curtain was open; it seemed like someone had forgotten to turn off “the workers” – the overhead halogen lights – and three shabby stage managers were sorting through a pile of rubbish on the stage. Why hadn’t they done this before they let the audience in? One of the stage managers was even smoking in the theatre! But then he pinched out the cigarette and put the stompie behind his ear while the other stage manager loaded a lot of the junk onto his back.

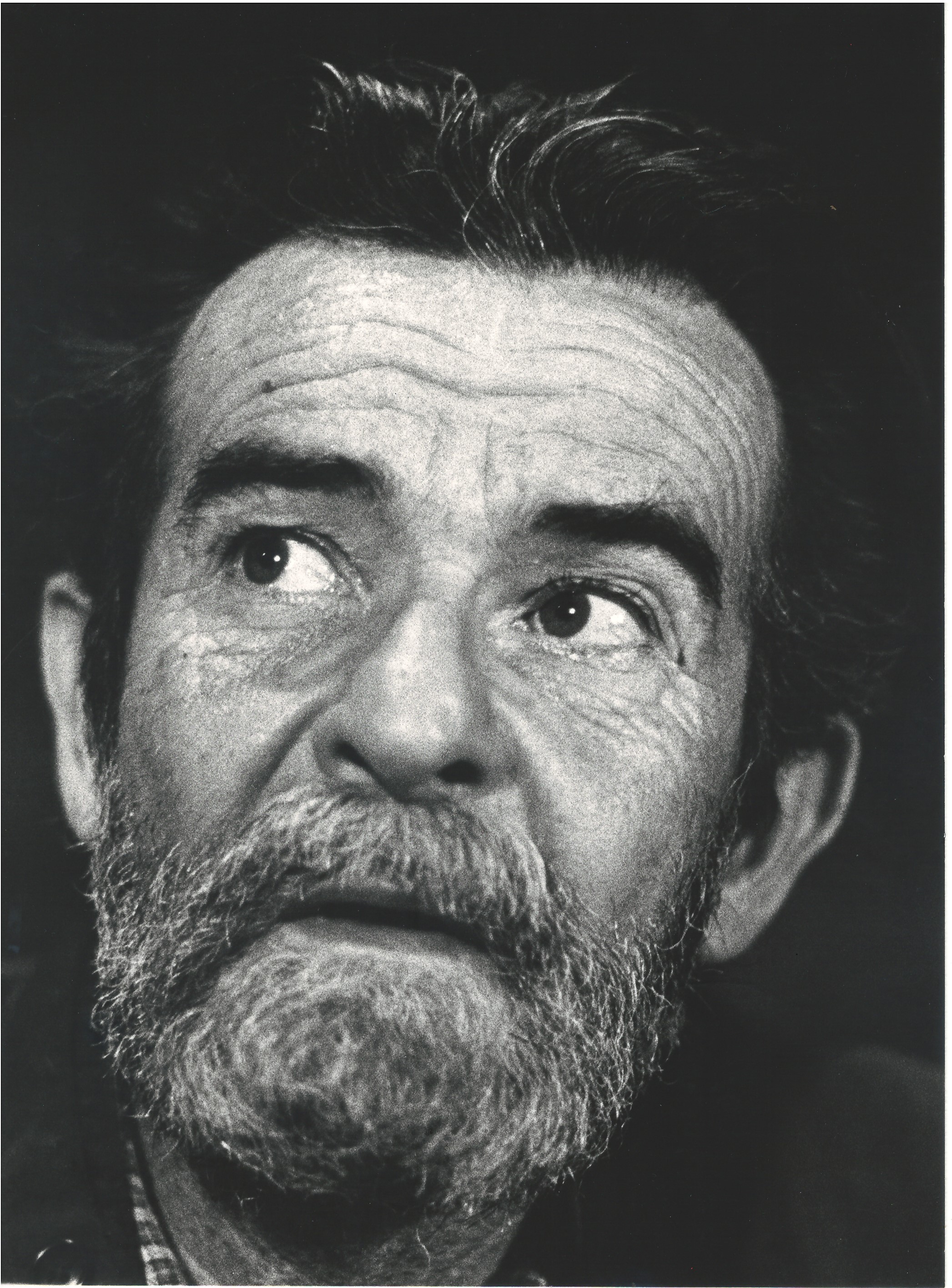

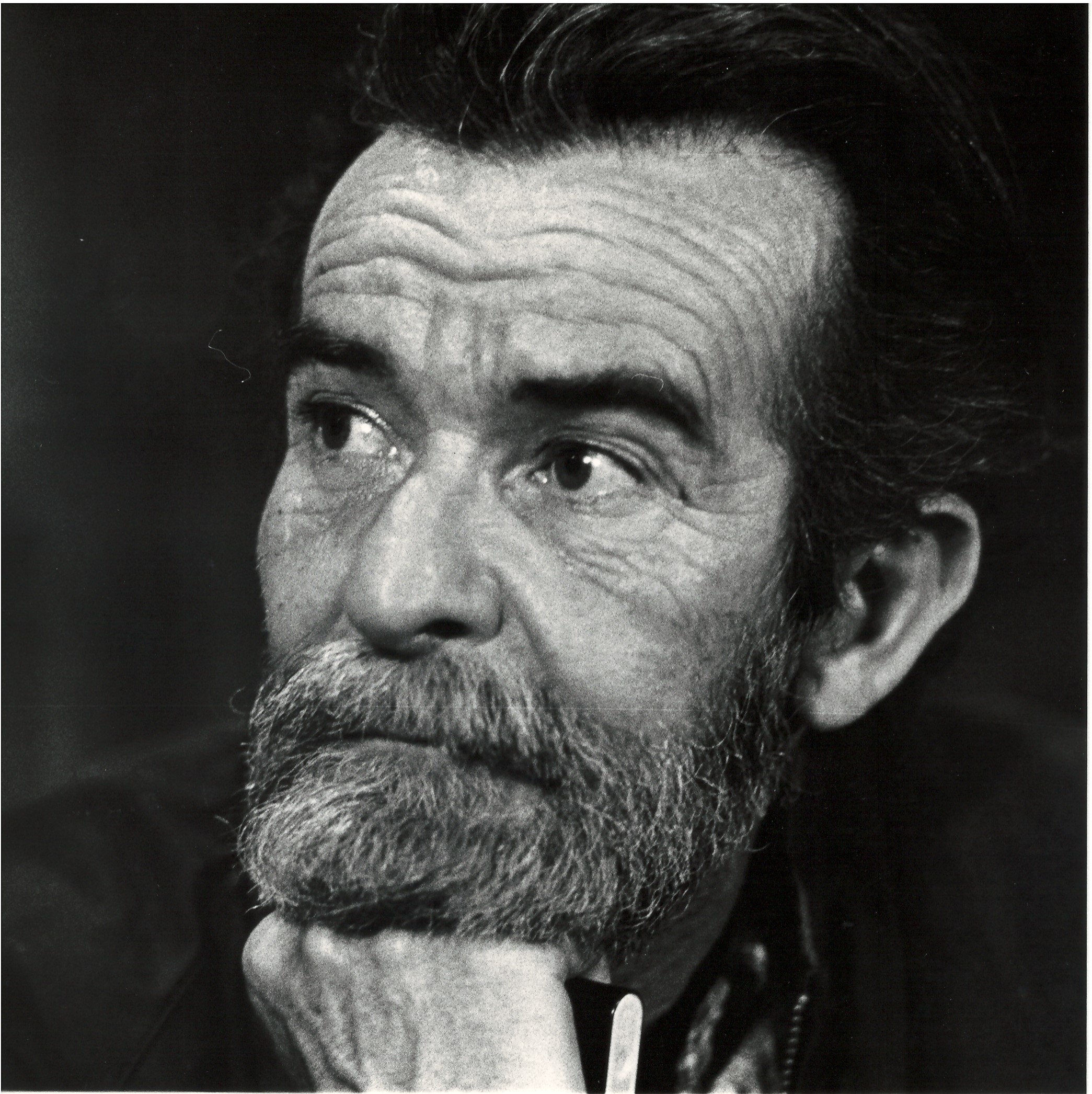

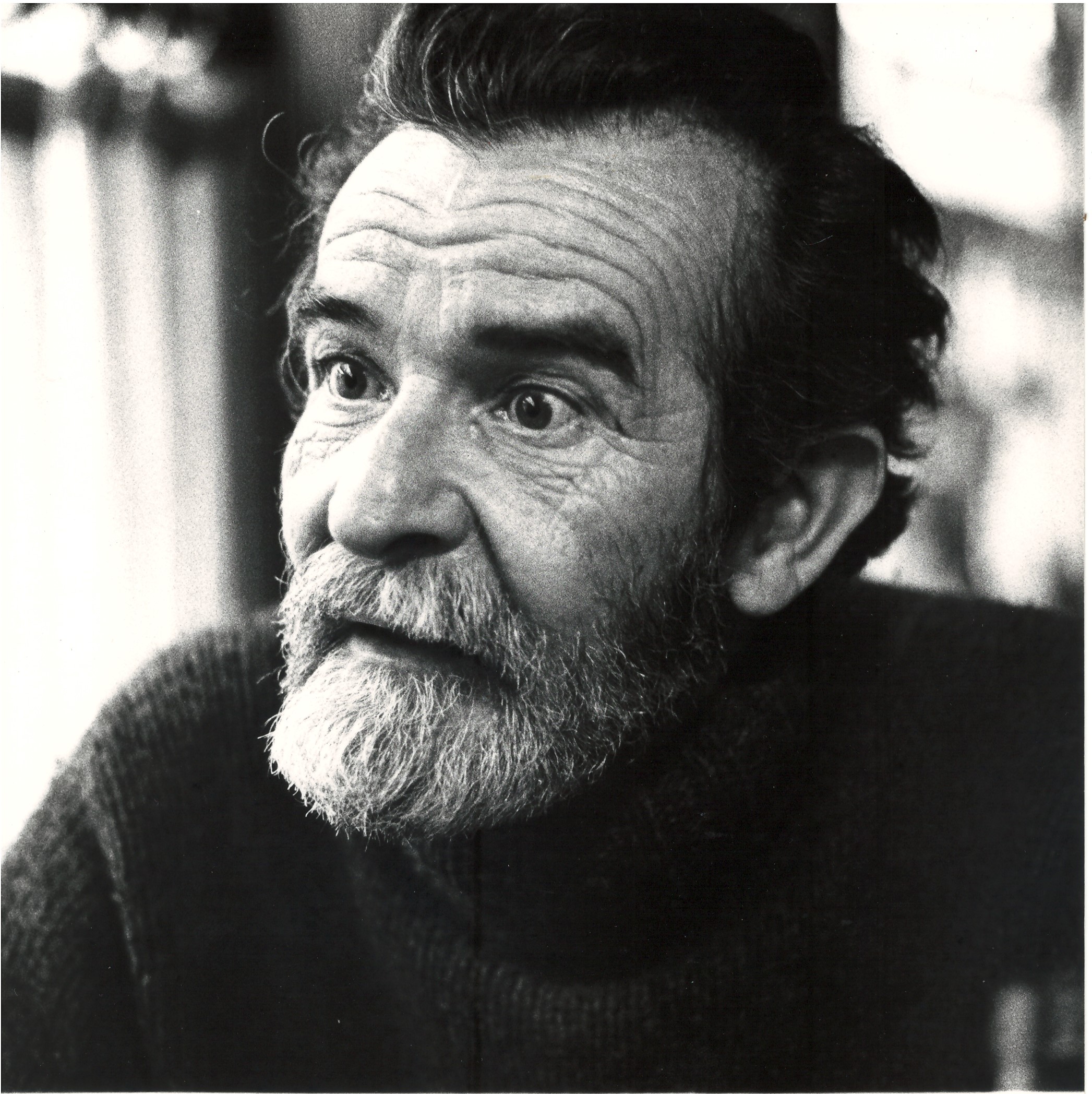

Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1981. Image: Anthony Akerman

Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1981. Image: Anthony Akerman

The woman tied a white doek around her head and the stage manager started walking. But he didn’t walk off stage. He started walking around the outer perimeter of the stage and continued this circular movement, and the woman started following him. The workers were switched off, the house lights dimmed and cross-faded with the stage lighting as they continued their walk. Eventually the man stopped and let the pile of junk on his back slide to the floor.

The woman looked around in disbelief and said, “Here?” Boesman (Athol Fugard) cleared his throat and spat on the ground while an exhausted Lena (Yvonne Bryceland) sat down, dug something out from between her toes and spat out the words, “Mud! Swartkops!”

What followed turned out to be the most riveting experience I’d ever had in a theatre.

I’d never been exposed to theatre that was modern, South African and politically relevant. Although essentially a love story in which an abused woman finds her voice, the play also exposed the inhumanity of apartheid’s forced removals under the Group Areas Act – the same Act that prescribed that the play itself could only be performed before segregated audiences and Outa – the old black man – had to be played by a white actor (Glynn Day), his ethnicity concealed by a balaclava and an army greatcoat.

After that I read every play written by Athol Fugard and saw the productions he directed for The Serpent Players in New Brighton, as many of them were put on at the Rhodes Little Theatre.

Because it was a “private theatre”, black actors were allowed to perform to racially mixed audiences – provided no tickets were sold, as that would have constituted a contravention of the Group Areas Act.

Don Maclennan prefaced each performance with a little speech asking the audience to donate generously to the silver collection and, afterwards, some of us drama students cracked the nod and were invited to cast parties at his house where Don and Athol drank from a 5-litre demijohn of Tassenberg, while Sheila Fugard (Mark Stannard’s mother’s friend) sat intensely in a corner wearing a beret and looking how I imagined a Parisienne Existentialist would look. Perhaps she was just wondering when they’d be able to afford a fridge.

There was an edginess to these cast parties. Consuming alcohol at racially mixed gatherings was against the law and we knew the Security Police were snooping around. They invariably attended performances and deliberately made no attempt to be inconspicuous.

We stood around engaging in stilted conversation with actors from The Serpent Players, including John Kani, who made quite an impression when he turned to us drama students and said with a smile, “When the revolution comes, we’ll kill nice liberals like you last.” We took it as a joke and managed a nervous laugh, but – together with the prospect of military camps – it seemed yet another good reason for leaving South Africa as soon as I could.

Before starting at the Old Vic Theatre School in Bristol, I spent six months in London immersing myself in theatre. In September 1973, I took my seat in the Theatre Upstairs at the Royal Court and saw the first London preview of Sizwe Bansi Is Dead. That experience eclipsed the 100 plays I’d seen so far that year. Nothing had been as visceral, nothing as powerful, nothing as exciting.

It seemed ironic that I’d come to the Mecca of World Theatre only to be most excited by a play from home. I introduced myself to Athol and reminded him of the cast parties at Don’s house. I don’t think he remembered me, but he was polite enough not to let on. When Sizwe Bansi went on a national tour, I saw it a few more times in Bristol and hung out with them like a groupie.

The following year, the Royal Court presented a South African Season of three plays. Two of them – Sizwe Bansi is Dead and The Island – were collaborations with John Kani and Winston Ntshona – developed through a process Athol characterised as “playmaking”. The third – Statements after an Arrest under the Immorality Act – was the first play he’d written alone in his workroom since Boesman and Lena.

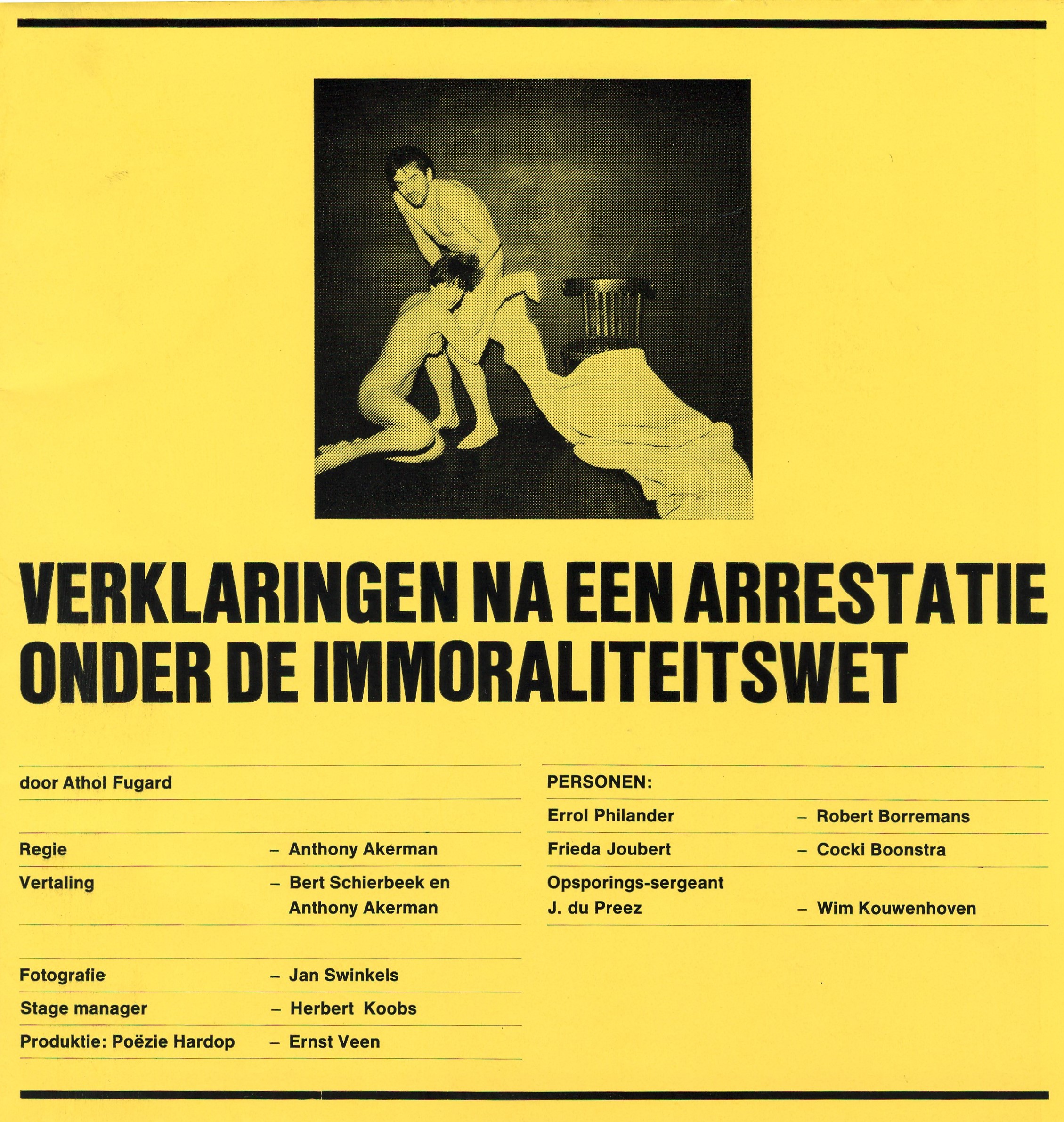

Statement by Athol Fugard, Amsterdam, 1976. Image: Supplied

Statement by Athol Fugard, Amsterdam, 1976. Image: Supplied

After seeing Ben Kingsley and Yvonne Bryceland in this production I knew I wanted to direct the play. It was a powerful indictment of an inhumane law and not an expensive play to stage: it required no set and the two leads were naked for most of the play.

After I’d finished my studies, I met Conny Braam at the home of South African friends in London. I told her about Statements and asked if any Fugard plays had ever been done in Dutch. She thought not and – as chairperson of the Dutch Anti-Apartheid Movement – she would have known. I suggested I direct the play in Amsterdam and she said she’d see what she could do to make that happen.

That’s how I ended up going to Amsterdam. In 1976, the first play I directed professionally – in other words, the first play I was paid to direct – was Verklaringen na een arrestatie onder de Immoraliteitswet in a translation by the Dutch writer Bert Schierbeek.

The original plan had been to go back to England after I’d directed the play, but I ended up staying for 17 years. During those years I directed five Fugard plays in Holland and one in Mexico. The last play I directed in Holland was My Children! My Africa! So my years in Amsterdam were book-ended by two Athol Fugard plays.

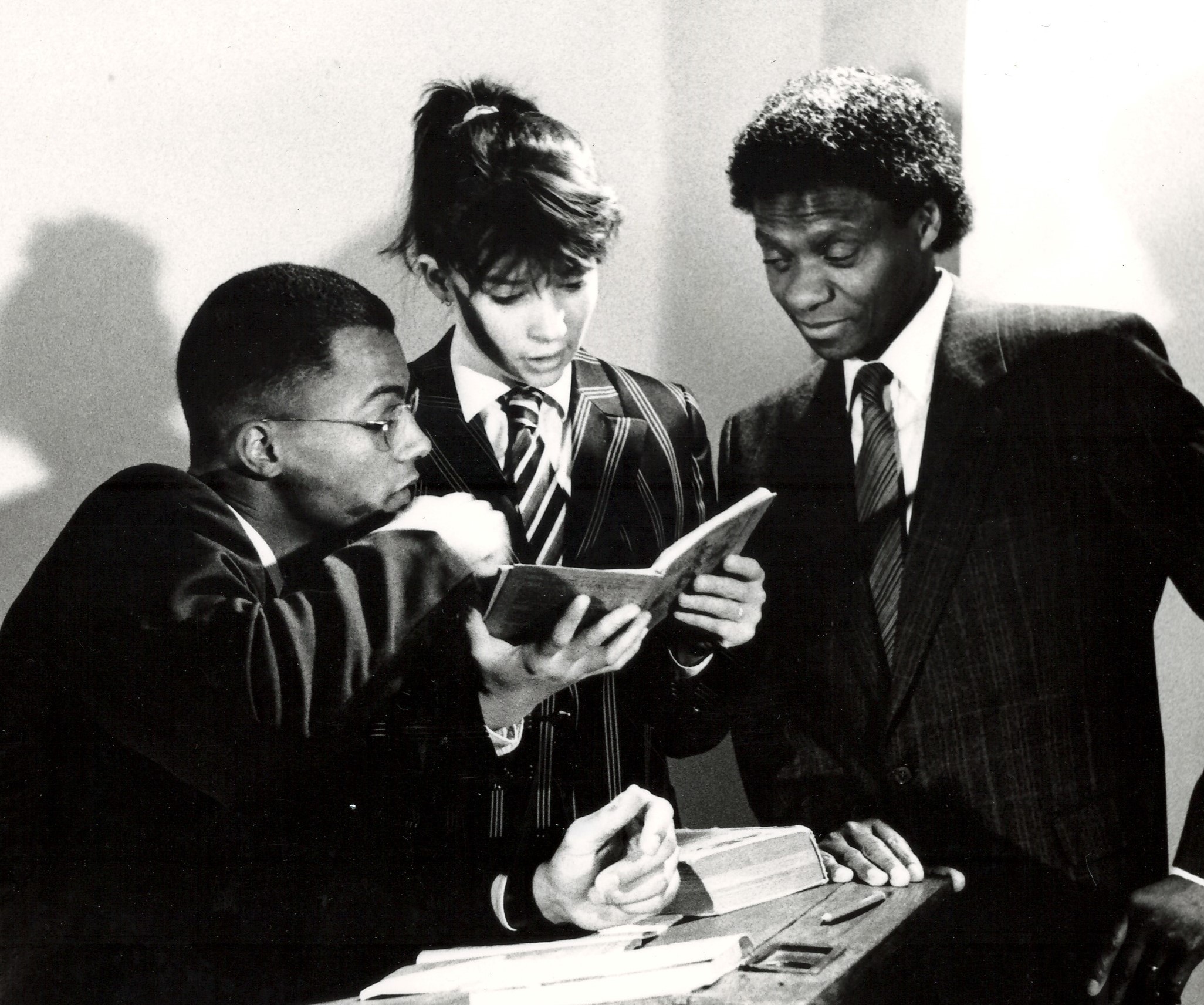

Mijn kinderen! Mijn Afrika! By Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1991. South African actor Joseph Mosikili played Mr M in Dutch. Image: Tet Lagemaat

Mijn kinderen! Mijn Afrika! By Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1991. South African actor Joseph Mosikili played Mr M in Dutch. Image: Tet Lagemaat

I don’t recall exactly when I first read A Lesson from Aloes but it moved me profoundly and I immediately knew it was a play I wanted to direct. I convinced a theatre company in Amsterdam to produce it and they suggested we invite Athol to attend the opening night and give press interviews. I doubted whether he’d be available. He’d recently acted in two films directed by Ross Devenish, directed A Lesson from Aloes for the Market Theatre, had taken the production to the National Theatre in London, and had directed a production for the Yale Repertory Theatre in Newhaven, which had then transferred to Broadway. He was an extremely busy man.

We extended an invitation through his agent, the redoubtable Esther Sherman at the William Morris Agency in New York, and Athol accepted.

I collected him on an early November morning at Schiphol Airport. He was on a high because he’d just finished writing “Master Harold” … and the boys.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gRIx-IPPICw

Driving back to have breakfast at my flat, he told me about the play and the final image when Sam and Willie – the two waiters in St George’s Park Tea Room – decide to put their bus fare into the jukebox and dance to a Sarah Vaughan song.

When he walked into my flat and saw the electric typewriter on my desk, he shrank back in horror and, in a pungent Eastern Cape accent, exclaimed, “Get rrrrrid of it!” Athol believed writing should be done using pen and ink. Once the play was written, he handed his handwritten manuscript over to a professional typist. Well, if he could afford to pay for a professional typist, he’d certainly reached a point in life where he could afford a fridge.

Athol was in an expansive mood and in 1981 he hadn’t yet given up drink. When we walked into a café, he’d announce, “This is my table”, and would pay for the drinks of anyone who joined him. November was the month when Beaujolais nouveau (a young French wine) became available and we drank copiously.

He acquitted himself well in interviews but was irked by constantly having to justify living in South Africa. He said it was home and quoted Anna Akhmatova’s poem “Requiem”, saying he was not “under some foreign sky”, but with his people when it happened.

Athol often described the act of writing his plays as “bearing witness”.

Some journalists couldn’t understand how the apartheid regime allowed him to get away with writing plays critical of government policy. When pressed, he acknowledged that in the past he’d had his passport withdrawn for four years, then went on to say that white liberals were no longer perceived as public enemy number one.

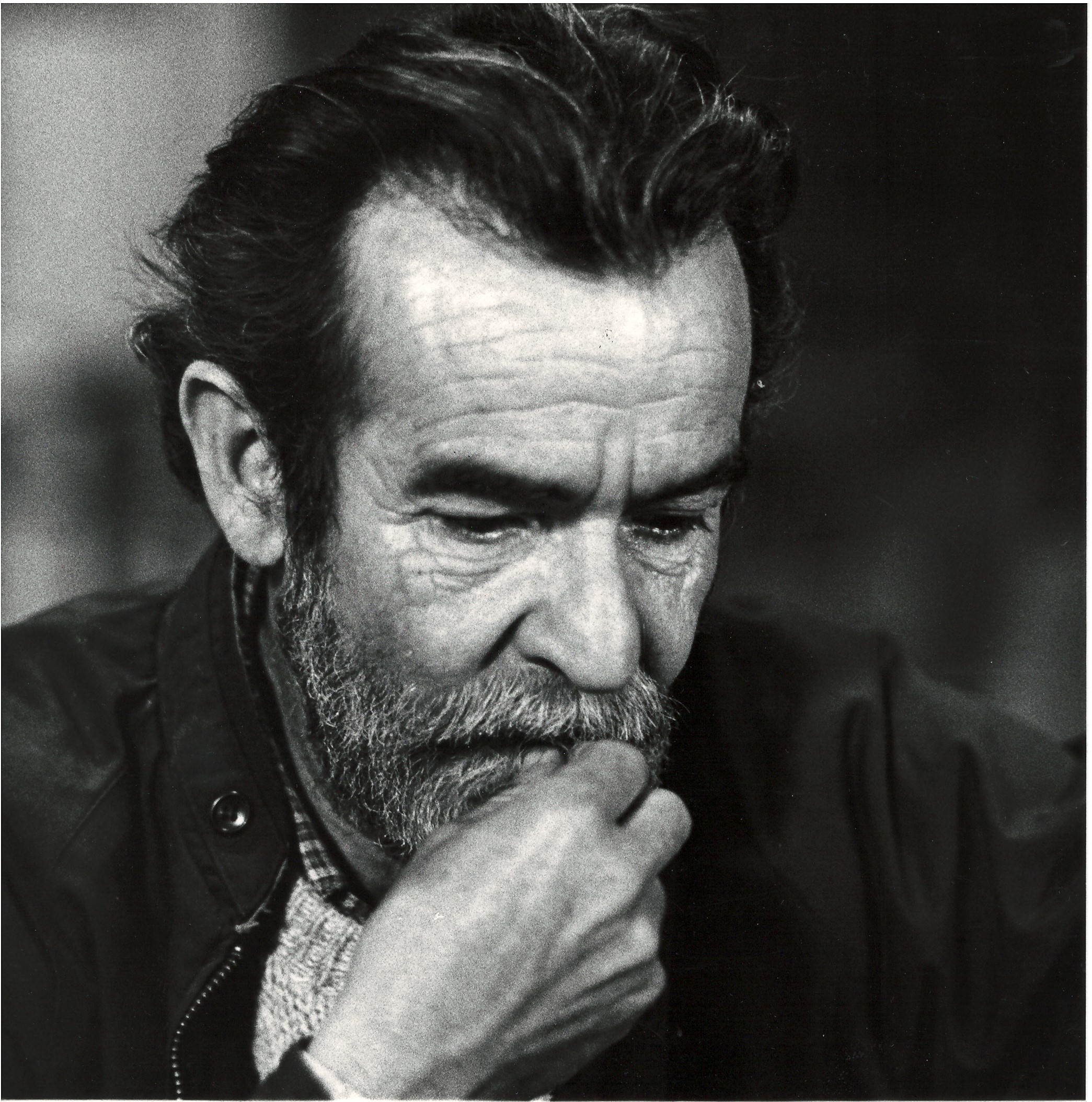

Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1981. Image: Anthony Akerman

Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1981. Image: Anthony Akerman

He said he was protected by his age and reputation and thought the government would look very bad if they persecuted an old man with a grey beard. He was only 49 at the time. It may have been the drink talking, but I think Athol liked to think of himself as an old man.

He spent over a week in Amsterdam and, on the Sunday, my girlfriend and I took him for a drive in the countryside. We stopped for lunch in Hoorn, a little town on the Ijsselmeer that once served as a jumping-off point for the Dutch East India Company.

Over a glass of Beaujolais nouveau, Athol talked about his relationship with fountain pens and how they were central to his rituals as a playwright. A pen – and it could be one he’d bought second-hand – wrote one play and was then retired. After that, it could be used for writing notebooks, but never another play.

He took out his Montblanc 149 and wrote something in the sepia-coloured ink he made from wild olives. He apologised for not allowing me to try it out but said you should never let anyone else use your fountain pen. That was my first lesson from Athol.

The second piece of advice he gave me had to do with secrets.

“When you start work on a play,” he said, “don’t tell anybody what it’s about. Keep it a secret until you get to the end. If you don’t, you may lose the urgency to tell your story.”

I’d sat opposite so many people in Amsterdam cafés who’d described characters in detail and given me a beat-by-beat account of the plot of a story they somehow never got around to putting down on paper. So it seemed like sound advice.

While in Amsterdam, Athol bought himself another second-hand fountain pen to use when he kept his appointment with the next play he planned to write. He was passionate about stationery and said he couldn’t find decent notebooks in South Africa, so we went to Vlieger, a shop specialising in art supplies and stationery.

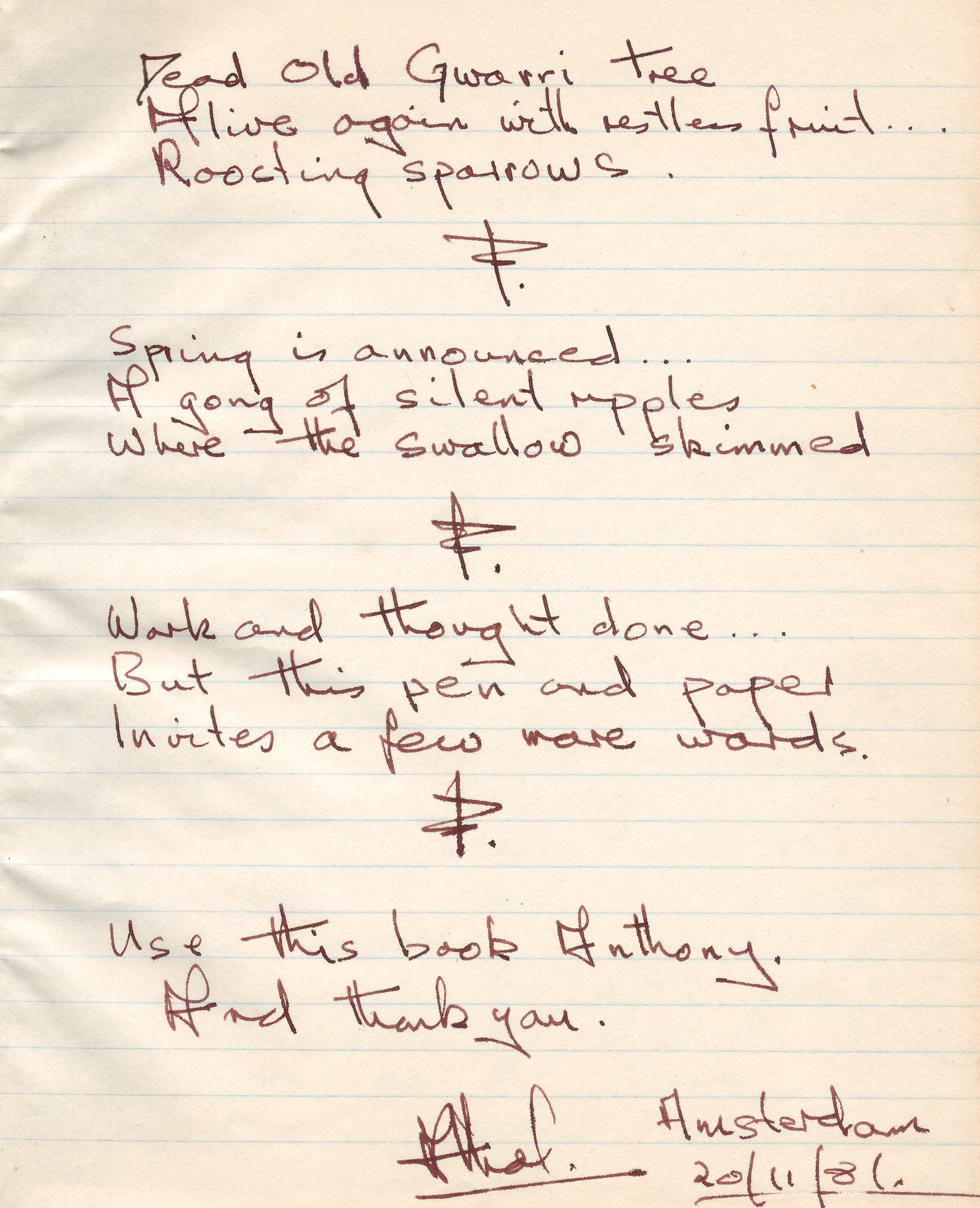

Athol stocked up on notebooks and also bought one for me, in which he transcribed three of his own haikus and wrote, “Use this book Anthony. And thank you.” It was an invitation to write, but up to that point in my life I hadn’t really given any serious thought to writing a play.

Notebook with Athol Fugard's inscription 1981. Image: Supplied

Notebook with Athol Fugard's inscription 1981. Image: Supplied

Three months later the situation had changed. I needed to take a break from working with Dutch actors and felt ready to accept Athol’s invitation. The year before, a friend who was an organiser for COSAWR (Committee on South African War Resisters) had suggested I write a play about the army. I passed at the time but now I felt ready to take it on.

Athol’s panegyric in praise of pen and ink had made an impression, so I took a walk down to the somewhat fortuitously named PW Akkerman (“specialists in Waterman, Parker and Montblanc”) and invested in an entry-level Parker. On 5 March 1982, I made my first entry in a companion notebook under the heading, “Army Play”.

I wrote in pen and ink and kept what I was writing a secret – even from my girlfriend. All I would tell her was that the play was set in the South African army and that the title was Somewhere on the Border. I think that irritated her and not even amorous pillow talk would induce me to say more until I’d written the words, “The End”.

When I’d completed the final draft, I typed it up on the typewriter Athol had told me to get rid of and airmailed a copy to him. When I didn’t hear anything, I became a bit anxious. Had he hated it?

His Notebooks were published in 1983 and I wrote to tell him how much I’d enjoyed reading them. On 17 August that year, I received a letter from him saying he'd been away for several months and apologising for the long delay in replying to my letter. The PS at the end of his letter read, “Your play hasn’t as yet arrived.” It never did. He may no longer have been public enemy number one, but someone was still intercepting his post.

I’d just begun rehearsing Somewhere on the Border in Amsterdam with a cast of South African actors when one of the actors told me his sister had read in the Cape Times that the play had been banned.

Brendan Boyle, who was working for UPI in Amsterdam at the time, made enquiries and received a telex from John Battersby in London. It confirmed that an announcement of the banning had appeared in the Government Gazette of 9 September 1983. I wasn’t surprised, but how did they get hold of a copy of the play?

The one or two copies sent to other people in South Africa had arrived and were accounted for. One of those people was Ampie Coetzee at Taurus Press. I’d sent him the play in the hope that they’d publish, but that was off the table now that it was banned “as a publication”.

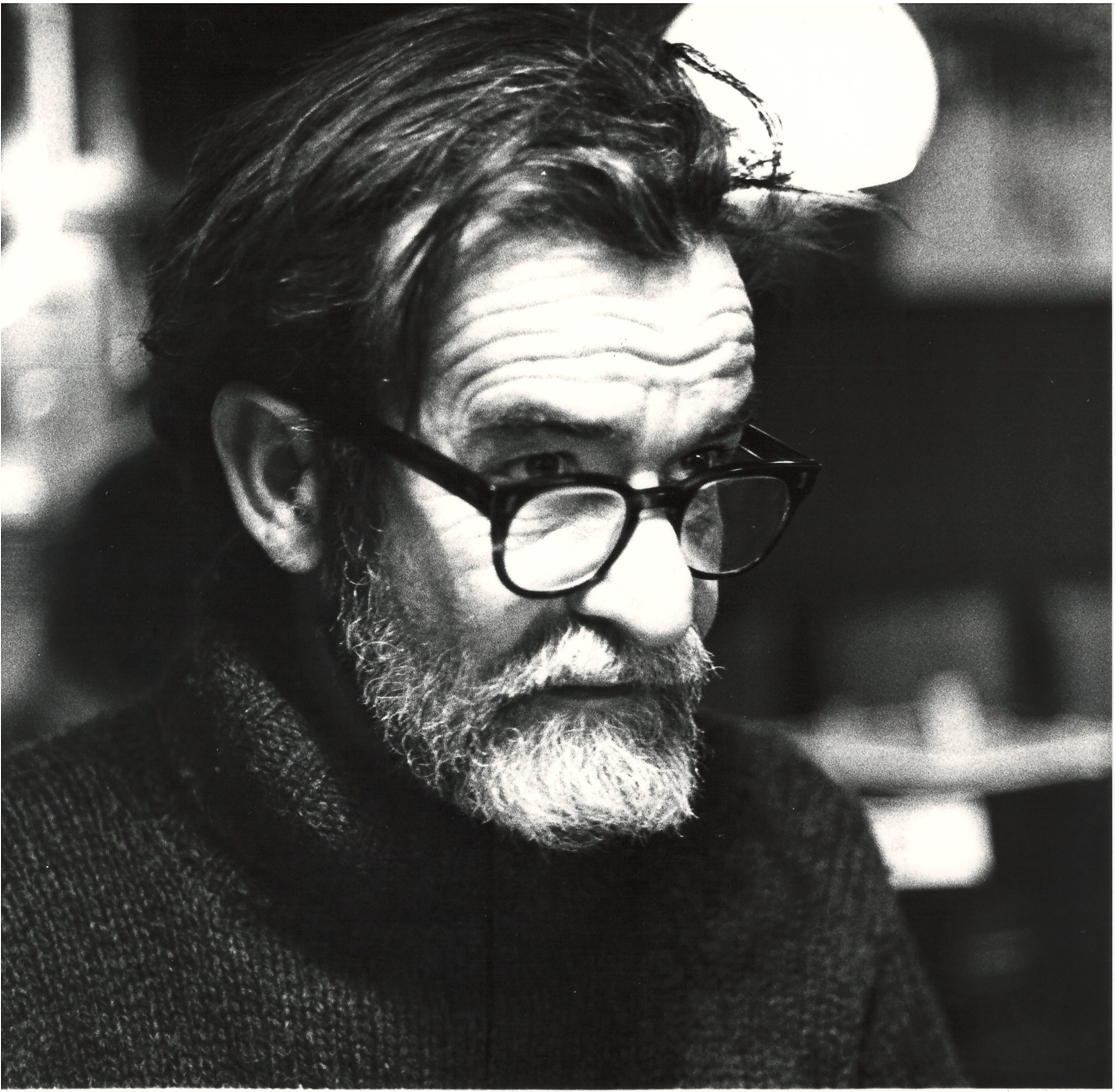

Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1981. Image: Anthony Akerman

Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1981. Image: Anthony Akerman

He suggested I write to the Directorate of Publications and ask for an explanation. This I did in May 1984 and I was informed by Mr SF du Toit, the Director of Publications, that the play had been deemed undesirable on two counts: the language was “offensive to the reasonable and balanced reader” and it was prejudicial to the safety of the state. The play could not be “distributed in the Republic of South Africa” so it wouldn’t have been smart to post another copy to Athol and I’m assuming that he’s never read the play.

As the page numbering they used to indicate the offensive passages coincided with the page numbering in the rehearsal script, I decided to ask Mr du Toit how the Directorate of Publications had come to be in possession of something that was for internal use only.

I wrote, “I did send one of the scripts to my colleague, the playwright Athol Fugard, in June 1983 and he has subsequently told me that it never arrived. Is this the script that came into the Board’s possession?”

Mr du Toit explained that any member of the public could submit a publication to the Directorate to find out whether, in the Board’s opinion, it was undesirable. “The Directorate does not however disclose the name of the submitter.” There is no doubt in my mind that this was Athol’s stolen copy.

Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1981. Image: Anthony Akerman

Athol Fugard, Amsterdam 1981. Image: Anthony Akerman

When Athol was born 90 years ago, there was little indigenous theatre in South Africa and none in English. With the notable exception of Stephen Black during the first two decades of the century, it was all imported. British theatrical companies disembarked in Cape Town, did countrywide tours of IW Schlesinger’s theatres by train, went on to play the Empire in the East and the Antipodes, then toured the country again on their return journey. It’s possible Athol saw one of these shows at the Opera House in Port Elizabeth (now Gqeberha), but his family lived in straitened circumstances. They probably couldn’t have afforded a fridge, let alone the luxury of theatre tickets.

World War 2 brought an end to international touring companies and local, professional theatre gained a foothold. Perhaps, as a 14-year-old Marist Brothers schoolboy, Athol was taken to see the Ffrangcon-Davies-Vanne Company performing Turgenev’s A Month in the Country. In 1948, the government finally provided funding to the newly formed National Theatre Organisation (NTO) which, in 1958, gave Athol his first paid employment in the theatre as a stage manager.

Unfortunately, the formation of the NTO coincided with the National Party’s election victory and, predictably, state funding brought with it political interference. However, it could also be argued that the harsher racist policies introduced by the National Party gave some impetus to South African playwriting.

Lewis Sowden’s The Kimberley Train (1958), Basil Warner’s Try for White (1959) and Athol’s The Blood Knot (1961) all explored the human cost of South Africa’s race laws.

By the time he wrote The Blood Knot, Athol already had two “township plays” under his belt. They had fairly large casts (which included such luminaries as Bloke Modisane, Ken Gampu, Zakes Mokae and Lewis Nkosi), but all the plays he’d go on to write would have small casts. That not only made economic sense, but it also became his hallmark as a playwright and he has often described himself as a miniaturist.

South African actors Ian Bruce, Joseph Mosikili in The Blood Knot, Amsterdam 1984.

South African actors Ian Bruce, Joseph Mosikili in The Blood Knot, Amsterdam 1984.

Image: Anthony Akerman

On international stages, Athol’s plays gave audiences a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the inhumanity of apartheid but, unlike Bertolt Brecht, he didn’t write with a political agenda.

Athol espoused Camus’ courageous pessimism, not Marx’s dialectical materialism. He wrote with love and compassion, often about marginalised characters who were victims of an evil political dispensation – and that made his political critique implicit.

Athol was a trailblazer, the first playwright to tell our stories in our diverse accents on an international stage.

I took Athol’s lesson to heart and have written all my plays with a fountain pen, but for two decades I wrote for television. When you enter a television writers’ room, you’ll see a sign on the wall that reads: “Leave fountain pens at the door.” That’s not actually true, but not once did I see a fountain pen in a writers’ room. It’s also a working environment in which there are no secrets. Stories are collectively “brainstormed” and “beaten out”, after which they’re “story-lined”, then written and rewritten by different people in a process inescapably reminiscent of a production line.

When I directed Athol’s La lección de la zabila (A Lesson from Aloes) at the Cervantino Festival in Guanajuato, the Mexican actors explained their attitude towards television and theatre: “Television is your husband because it pays; theatre is your lover because you do it for free.”

La leccion de la zabila (A Lesson from Aloes) Cervantino Festival, Mexico 1988. Image: Supplied

La leccion de la zabila (A Lesson from Aloes) Cervantino Festival, Mexico 1988. Image: Supplied

In 1997, I invested in a Montblanc 149. It’s the same make and model as the pen Athol showed me all those years ago in that café in Hoorn. The last time I used it to write a play was in 1999 when I wrote Comrades Arms.

A few months ago, when I sat down at my desk, filled that pen, wiped the residual ink off the nib with a soft cloth and prepared myself to write Leading Ladies – my first stage play in 23 years – my thoughts strayed to Athol. I couldn’t remember when I’d last seen him, although I’d seen most of his plays over the past three decades, some of which I’d liked more than others.

I recalled that he was turning 90 this year. Is he still writing plays? They say Sophocles wrote Oedipus Rex when he was 90, so there’s no good reason why he shouldn’t be working on a new play. I was 32 when Athol transfixed me with his gaze and spoke so passionately about writing in pen and ink and the importance of keeping writing secrets.

Now he’s 90 and I’m an old man with a grey beard.

Back in 1968, when Mark Stannard told me about his mother’s friend’s husband – the playwright who couldn’t afford a fridge – it seemed inconceivable to me that anyone in their right mind would choose to be a playwright. Perhaps that still holds true and nobody in their right mind would choose to be a playwright, yet I can’t imagine ever having done anything else with my life.

What I do know, however, is that had I become an advertising executive, I’d have one of those state-of-the-art, door-in-door fridges with a smart inverter compressor, linear cooling and an external ice dispenser in the door. DM/ML

Anthony Akerman is a playwright who has also written extensively for radio and television. His award-winning stage plays include Somewhere on the Border, Dark Outsider and Old Boys. His recently completed memoir Lucky Bastard – which primarily focuses on how his life was shaped by adoption – is currently being considered by a publisher. He has just finished a new stage play, Leading Ladies, set in the Standard Theatre in Johannesburg during World War II. It’s a celebration of the theatre at a time when, like now, it faces an existential threat. The play recently received the 2021 Writers Guild of South Africa (WGSA) Muse Award as Best Theatre Play Script.

[hearken id="daily-maverick/9591"]

La leccion de la zabila (A Lesson from Aloes) Cervantino Festival, Mexico 1988. Image: Supplied

La leccion de la zabila (A Lesson from Aloes) Cervantino Festival, Mexico 1988. Image: Supplied