What follows is a lightly edited excerpt from Akerman’s memoir Lucky Bastard.

***

Why don’t you write an army play for us?

I’ve never written a play.

There’s always a first time.

Well, maybe, but I’m too busy.

Michael Smith was a member of the Committee on South African War Resistance (COSAWR) and we were having a drink in my flat in the Amsterdam red-light district. Britain and the Netherlands gave political asylum to white conscripts who refused to fight on the border, and COSAWR offered these draft dodgers support and campaigned against South African military intervention in southern African states. Michael was one of those national servicemen who’d been given electroshock aversion therapy by Colonel Aubrey Levine — a.k.a. Dr Shock — to cure him of his homosexuality. It hadn’t worked.

A year later my situation had changed and I recalled the conversation I’d had with Michael. As I started thinking about the play that would become Somewhere on the Border, it occurred to me that it had been 15 years since I’d done my military service and that I’d been away from South Africa for nine. Was the South African military still my problem? A few days later I received my answer. It was an official brown envelope bearing a Pretoria postmark. Enclosed in the envelope was a form for the Annual Registration of Reservists. I was required to complete it and immediately return it to Defence Headquarters. I had no idea I was still registered as a reservist in the South African Defence Force and that Magnus Malan had not abandoned hope that I’d return and do a stint of patriotic border duty. Now I knew why I had to write the play.

In 1982, I began exploring possibilities of staging the play in the Netherlands with a South African cast. I teamed up with Anky Mager, a twenty-six-year-old Theatre Studies graduate, who helped me find funding, register a foundation called Thekwini Theater, book the theatres, draw up the actors’ contracts, find their accommodation and — as I was not yet a Dutch citizen — apply for gun licences for five FNs and an AK-47.

Soon after rehearsals began, I heard a rumour that the play had been banned in South Africa.

I contacted Brendan Boyle, who I’d first met when we were at Rhodes. He was then Bureau Chief for United Press International in Amsterdam and I asked him to investigate. He contacted John Battersby of the Argus London Bureau and received a telex confirming that the Cape Times had carried the story. Brendan also asked a journalist in South Africa to send a photocopy of the relevant page from the Government Gazette in which Somewhere on the Border was declared an undesirable publication in terms of Section 47(2) (a) + (e).

Telex confirming that the Cape Times had carried a story mentioning the banning of Somewhere on the Border in September 1983. (Image: Supplied by the author)

Telex confirming that the Cape Times had carried a story mentioning the banning of Somewhere on the Border in September 1983. (Image: Supplied by the author)

I’d already approached Ampie Coetzee to ask if Taurus would consider publishing the script, and when news of the banning came through he urged me to write to the Directorate of Publications asking them to furnish reasons for their decision. I received a reply from the Director of Publications, Mr SF du Toit. He fastidiously — exhaustively would have been too time-consuming — itemised the offensive obscenities and then explained that as I had, “in the closing parts of the book”, placed the South African Armed Forces “in an extremely bad light” it was undesirable because it was “prejudicial to the safety of the state”.

The play, he explained, was “found to be undesirable” as a publication and “may not be distributed in the Republic of South Africa”, but, he added, “a play could be performed if the parts which were found to be offensive are deleted”. I’m afraid I did my best to ensure that copies of the banned script were distributed as widely as possible by anyone visiting South Africa.

A few years later I received a request from an unexpected quarter.

A group of actors working for the Performing Arts Council of the Free State in Bloemfontein wanted to take the play, as an independent production, to the fringe of the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown. It opened in 1986 during a nationwide State of Emergency and immediately connected with audiences while military vehicles patrolled the streets. The Cape Times proclaimed it “an overnight success” and concluded by saying, “It is possibly the ultimate anti-war statement in South African theatre”. It was game on.

Press clippings from the 1986 National Arts Festival and Cape Town, January 1987. (Image: Supplied by the author)

Press clippings from the 1986 National Arts Festival and Cape Town, January 1987. (Image: Supplied by the author)

Sunday Times 18 January 1987. Priceless publicity courtesy of the South African Defence Force. (Image: Supplied by the author)

Sunday Times 18 January 1987. Priceless publicity courtesy of the South African Defence Force. (Image: Supplied by the author)

The play had runs in Cape Town — where the military police confiscated the uniforms the actors were wearing as costumes — in Bloemfontein — where there were bomb scares — and in Johannesburg, where two of the actors were violently assaulted by members of the Civil Cooperation Bureau (CCB), a government-sponsored death squad. This grabbed newspaper headlines and had the unintended consequence of ensuring Somewhere on the Border played to full houses.

Press clippings from Johannesburg, February 1987. (Image: Supplied by the author)

Press clippings from Johannesburg, February 1987. (Image: Supplied by the author)

Before the opening night in Cape Town, I’d started thinking about going home for a visit. I knew it would be going back on the vow I’d made never to return to South Africa while apartheid was still the law, but I now felt the situation had changed. Perhaps I’d changed and felt my play had been a calling card. I also felt that being a Dutch citizen — I’d naturalised in 1983 — would afford me some protection. But there was one problem: I’d need a visa.

I booked my ticket in advance, as I thought that would give me an air of confidence befitting a man with a clear conscience. I did my best not to appear nervous in front of the security cameras when I went through the electronic gates of the South African Embassy in The Hague and handed my application to a Dutch porter sitting behind bullet-proof glass. A week later, I received what looked like a generic letter confirming receipt of my application and telling me not to make any travel plans. The next day I received a call from the embassy asking me to come in for an interview.

I dressed for the occasion, hoping I looked more of an artist than an activist. PW Botha had called a general election for 6 May and the embassy was exercised with weeding out visa applications from mischievous Dutch journalists who were pathologically predisposed to write negative reports. I hoped that would give them less time to worry about me. When I arrived, I was told I had a meeting with the Second Secretary, a Miss Marina L Minnie. She kept me waiting because she’d been in a meeting with a Mr de Meyer who, it transpired, would sit in on our interview. Miss Minnie wasted no time coming to the point.

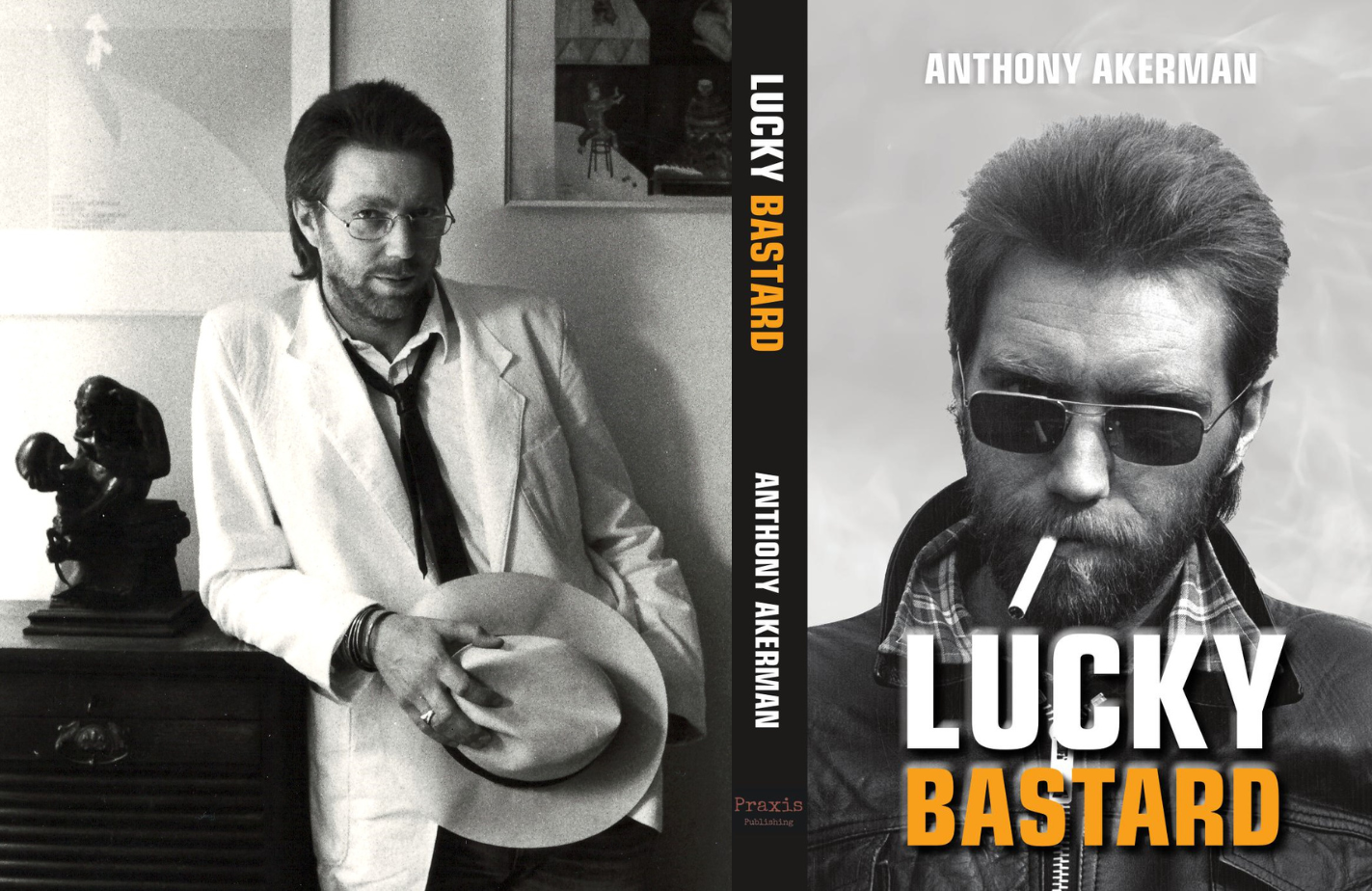

Minus the hat, the sartorial style Anthony Akerman adopted for his visa interview at the South African Embassy in The Hague. Photo: Supplied by the author.

Minus the hat, the sartorial style Anthony Akerman adopted for his visa interview at the South African Embassy in The Hague. Photo: Supplied by the author.

You know why you’re here?

Well, I presume it has to do with my visa application.

We have to check all people who’ve renounced their citizenship.

They spoke Afrikaans. I also spoke some Afrikaans and apologised for my Dutch accent, then coffee arrived. But this wasn’t a social occasion and Miss Minnie ignored the coffee.

What is your attitude towards South Africa?

That’s quite a broad question.

Do you still feel the same way you did in 1981 when you made negative comments in the media?

Where was that?

It was in an article.

Which article?

In Elsevier Magazine.

I noticed Miss Minnie had a bulky dossier from which she extracted the article. It looked like they had more information on me than I did. I wondered if they knew Somewhere on the Border had been banned. Did they know about the controversy stirred up by the production? It had received wide press coverage in South Africa, and Dutch newspapers had also carried the story. Although I didn’t know it at the time, Johnny Jones — a draft dodger who’d been given political asylum and was stage manager on the Amsterdam production — was also a spy reporting to a handler, quite possibly at the embassy.

My mouth was dry. I needed a sip of coffee. I decided to tell them what I thought they wanted to hear and to do that in a way that wouldn’t make me look like an implausible fraud. PW Botha’s government was trying to convince the world that meaningful reform was on the agenda and, to that end, had even appointed Mr Frank Quint, a “coloured”, as ambassador to the Netherlands. I tried to manoeuvre in that space.

We’re not the people who are going to decide whether you can get a visa. That decision can only be taken by the Minister of Home Affairs.

Stoffel Botha, Mr De Meyer added helpfully.

We simply make a recommendation.

Sometimes he acts on our recommendations and sometimes he doesn’t.

I see.

Your application is already in Pretoria.

Mr De Meyer said he was there for “the legal side of things”. I’m still not sure what that meant, but he immediately asked what I thought of the ANC. I deflected the question, saying I thought the government should follow the lead given by big business and start talks with the ANC leadership. Miss Minnie interjected, saying the government had already offered to do so, but the ANC wouldn’t call off the armed struggle. Mandela could be a free man, she added, if he’d just renounce violence. I made no comment.

Yes, I obviously knew some people who were members of the ANC and, no, I wasn’t a member myself. I’d never join any political party. Why not? As an artist I needed to be unconstrained by political ideology and only accountable to artistic truth. It’s something I believe but, God, I cringed at how excruciatingly pretentious it sounded. Had I ever donated money to the ANC? No, I hadn’t!

After an hour, we got up and Miss Minnie gave me her business card. She really seemed eager to help. I couldn’t escape the feeling they wanted to win me over to their way of thinking, wanted me to agree with them, wanted my approval, wanted me to believe they were not bad people. I wasn’t all that sure about Mr De Meyer, but I didn’t think Miss Minnie was a bad person. “If you go back to South Africa,” she said, “I think you’ll want to live there again.” She smiled at me and I thought she could be right.

When I got back to Amsterdam, I opened my journal and wrote up a detailed account of this interview. Mr De Meyer’s question about donations to the ANC is duly recorded, but at the time I made no reference to the £50 donation I’d arranged after Mayibuye, the ANC’s cultural collective, had given a performance I’d arranged while I was a student in Cardiff. I’d completely forgotten! Thank God, otherwise Mr De Meyer would have had me on the back foot.

But perhaps he’d seen a copy of the incriminating letter in which I mentioned this to Dad in Miss Minnie’s dossier and thought I was a bloody good liar. But how would I stand up under interrogation? Works in the theatre; thirty-seven and unmarried; wrote a play with an all-male cast; wears a silk tie, a white seersucker jacket and carries a trench coat like Humphrey Bogart’s in Casablanca; no doubt about it, he’s a moffie and wouldn’t last a single round of questioning by the Special Branch.

Two weeks elapsed and I still hadn’t heard a word. Whenever I called the embassy, I was told a decision had not yet been taken. The election came and went. With what might have been mistaken for messianic delusions, I’d booked to fly on Ascension Day. Dad asked his attorney to follow up, but Home Affairs would only say that the matter was still under consideration. I delayed my flight but didn’t tell De Meyer. I kept phoning and he’d say, “No news, sir, they’re keeping us in the dark.” Then, the day before I was supposed to have left, he called.

De Meyer, speaking.

Have you got any news?

Your application has been refused, sir.

Did they say why?

No reason was given, sir.

Surely they gave a reason?

The government is not obliged to give reasons, sir. But what I can tell you is that the decision came from the top.

An article in The Star, 29 May 1987. (Image: Supplied by the author)

An article in The Star, 29 May 1987. (Image: Supplied by the author)

I was no longer in self-imposed exile. I was now officially persona non grata in the country of my birth. But I was only thirty-seven and comforted myself with the thought that I could outlive the National Party government. I immediately contacted the press. Garner Thomson of the London Star Bureau filed a story that appeared in The Star the day I was to have landed in Johannesburg. That was a homecoming of sorts. DM

Lucky Bastard is available at leading bookstores, as well as on Takealot, Amazon and Kindle. Reviewers can direct all enquiries to ikesbooks@iafrica.com

Anthony Akerman will be discussing Lucky Bastard at Exclusive Books in Cavendish Square, Cape Town on Tuesday 11 March 2025 and, on Saturday 15 March, he’ll take part in a panel discussion on “the art of memoir” at Books on the Bay in Simon’s Town.

An article in The Star, 29 May 1987. Image: Supplied by the author.

An article in The Star, 29 May 1987. Image: Supplied by the author.