I got to know André Brink at Rhodes University when I was a student in the Speech and Drama Department. His lectures — invariably given without referring to a single note — on Federico Garcia Lorca’s Yerma and Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author were erudite, edifying and inspiring.

Although he was an academic, I always thought of him as a writer — the first real writer I’d met. Not that I’d read anything he’d written. Of course, other academics had published poetry and plays but they seemed, in the best sense of the word, amateurs. André Brink was a professional who — during university vacations — directed his own plays for the Performing Arts Councils, until the powers that be decided that he and his work was “volksvreemd”.

During the 1960s, he and other Afrikaans playwrights experienced pushback from the Performing Arts Councils. Those who sat on the boards of these bodies were wary of the modern and alien ideas that increasingly found expression in the work of the literary grouping known as the Sestigers. If anything too controversial got past them, they’d be answerable to their political masters. If they were worried about a play, all they had to do was say they didn’t believe it was of a sufficiently high artistic standard. It was soft censorship.

I got to know André first as a mentor and then as a friend. After I left to go to theatre school in the UK, we corresponded regularly as he was interested to hear first-hand accounts of new plays and productions in London — and I valued his perspective on what was happening back home. When I left the country, André was 37 and I was 23.

On 6 August 1973, André mentioned he was correcting the galley proofs of a novel he’d written and said he hoped it would be out in late September. It was hard to keep up because his output was bewilderingly prodigious.

***

Prior to legislated censorship, the Customs Management Act (1913) prohibited the importation of articles that were considered "indecent, obscene or objectionable". Similar situations obtained in the United Kingdom and the United States where, in 1922, copies of James Joyce’s Ulysses shipped from France were impounded in Dover and New York.

Legislated censorship in South Africa began with the Entertainments (Censorship) Act of 1931, which was enacted primarily to “regulate cinematograph films”. However, in 1934 powers under this Act were extended to include imported books and periodicals. It was under this legislation that Stuart Cloete’s Turning Wheels — considered an offensive portrayal of Voortrekker conduct on the Great Trek — was banned in 1937.

Taken together, the Suppression of Communism Act (1950) and the General Law Amendment Act (1963) were used to ban people and a banned person’s words could not be quoted. That was a particularly brutal form of censorship. The novelist Lewis Nkosi has described how, when he left the country, a blanket ban was imposed on all his writing. This was a fate he shared with other black writers who left the country on exit permits.

Read more in Daily Maverick: The Gods Who Send Us Gifts: An Anthology of African Stories

In 1954, DF Malan’s apartheid government established a Commission of Inquiry into Undesirable Publications — the Cronjé Commission — and their recommendations resulted in the enactment of the Publications and Entertainment Act of 1963, which established the Publications Control Board (PCB). Only recently did it occur to me that the word "censorship" used so unabashedly in 1931 had now been supplanted with the deceptively euphemistic notion of "control". During the decade in which this Act exercised control over publications, 8,768 were declared undesirable — i.e., banned.

According to Peter McDonald’s The Literature Police (2009), the first local novel to be banned was An Act of Immorality. Des Troye — nom de plume of Simon Meyerson — was soon joined by Wilbur Smith, Nadine Gordimer and a roll call of many of the most prestigious writers in world literature.

Although the PCB did receive complaints against several Afrikaans literary works — including Etienne Leroux’s 1962 novel Sewe dae by die Silbersteins, Breyten Breytenbach’s collection of poems Die ysterkoei moet sweet (1964) and André Brink’s novels Lobola vir die lewe (1962) and Miskien nooit (1968) — during the first decade, no Afrikaans literary work had been declared undesirable. That was all about to change.

As he corrected the galley proofs of his new novel, André would have known a head-on collision with the PCB was inevitable. Although he didn’t mention this at the time, in his 2009 memoir A Fork in the Road, he relates how he’d submitted the manuscript to his publisher — Human & Rousseau — and they’d turned it down "for fear of censorship". Apparently, he waited a year before approaching Daantjie Saayman, an independent publisher who published Breyten Breytenbach’s poetry.

Read more in Daily Maverick: My friend André Brink, the Afrikaner roots I didn’t want, and the secret I wish I’d told him

The main character, Josef Malan who under apartheid race classification was Coloured, trains at theatre school in London where he becomes romantically involved with an English woman called Jessica Thomson. They return to South Africa where he establishes an agitprop theatre company to expose the iniquities of apartheid. As if that weren’t enough, he kills Jessica and is put on trial for murder. And there was much more in the novel that the pious deemed blasphemous.

The looming confrontation was no longer going to be with the pusillanimous arts council board members intoning the artistic-merit mantra; this was where phrases such as "offensive to the reasonable and balanced reader" and "prejudicial to the safety of the state" were used when determining the desirability of a publication. And censorship was destined to be more rabid since cabinet had put a new bill before Parliament to close the loopholes in the current Act and remove the right to appeal a banning in a court of law.

***

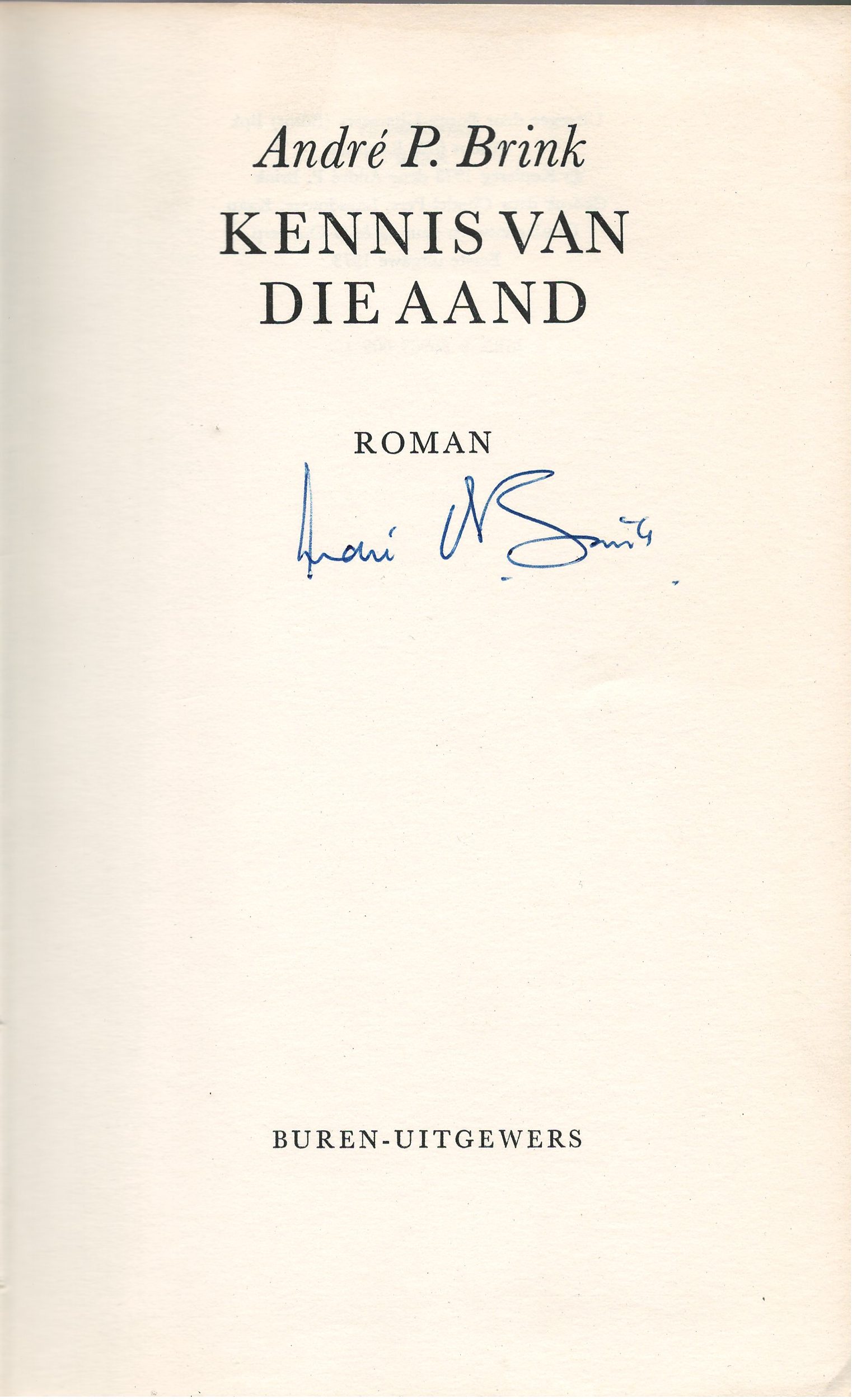

Shortly before the novel was published, I received a letter from André asking how good my Afrikaans was and whether I’d like a copy of the novel. I jumped at the offer, although I hadn’t read anything in Afrikaans since doing obligatory first-year Afrikaans/Nederlands five years previously. After the book launch, he posted me a copy and reported on the bacchanalian revelries with the bibulous bon vivant Daantjie Saayman.

In a day and age when postal services worked astoundingly well, I’d received the book by late October. It was a thrill as it was the first inscribed and autographed book I’d ever received from an author — and it remains a treasured possession.

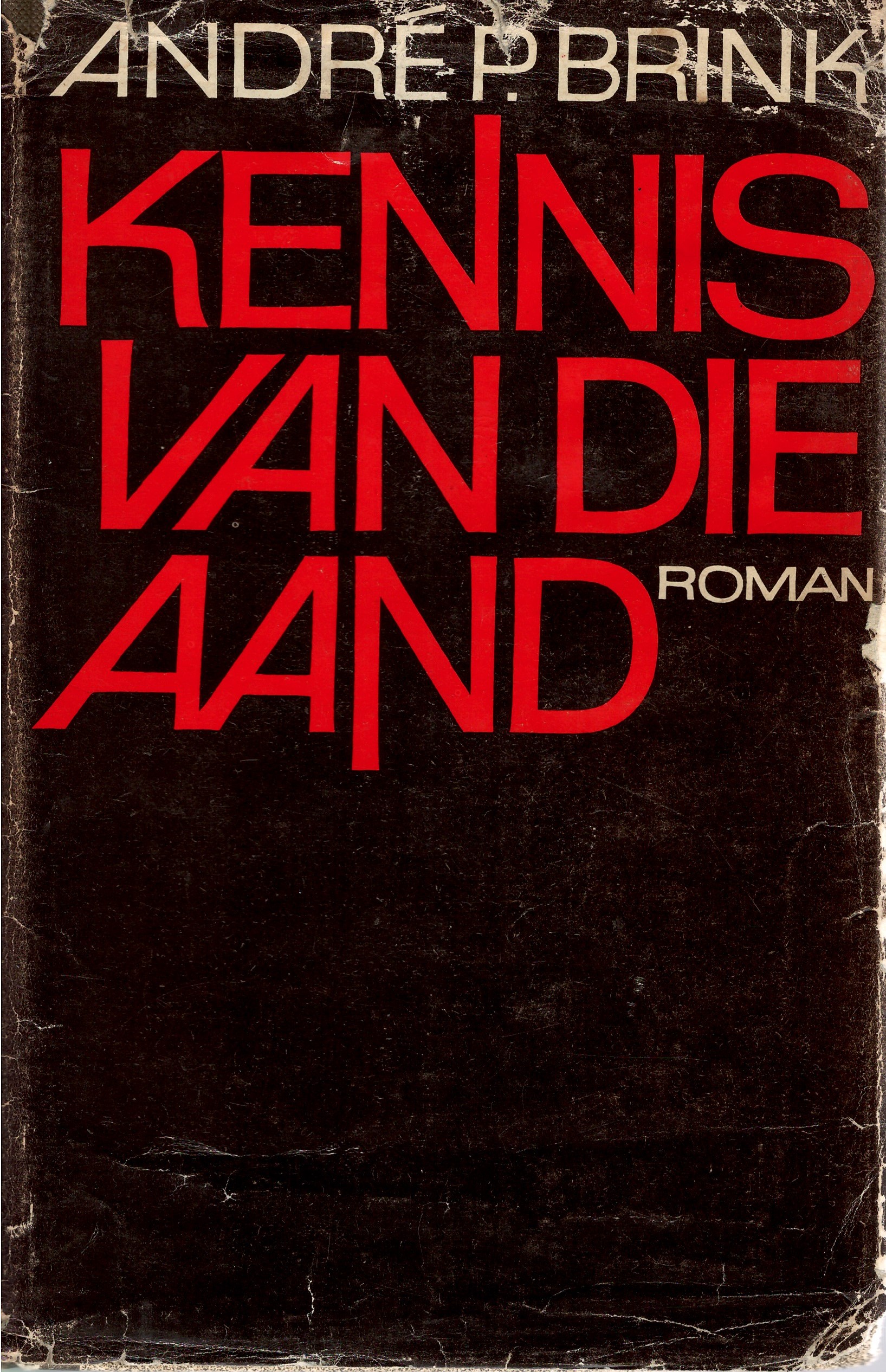

'Kennis', 1st edition, Buren. 1973. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

'Kennis', 1st edition, Buren. 1973. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

Anthony Akerman’s signed copy of ‘Kennis van die Aand’ (Image: Anthony Akerman)

Anthony Akerman’s signed copy of ‘Kennis van die Aand’ (Image: Anthony Akerman)

He mentioned he was going to translate the novel into English. I’m not sure if he was encouraged to do so by reviews that hailed the novel as "world literature" or whether he was looking for another outlet in the event of the novel being banned.

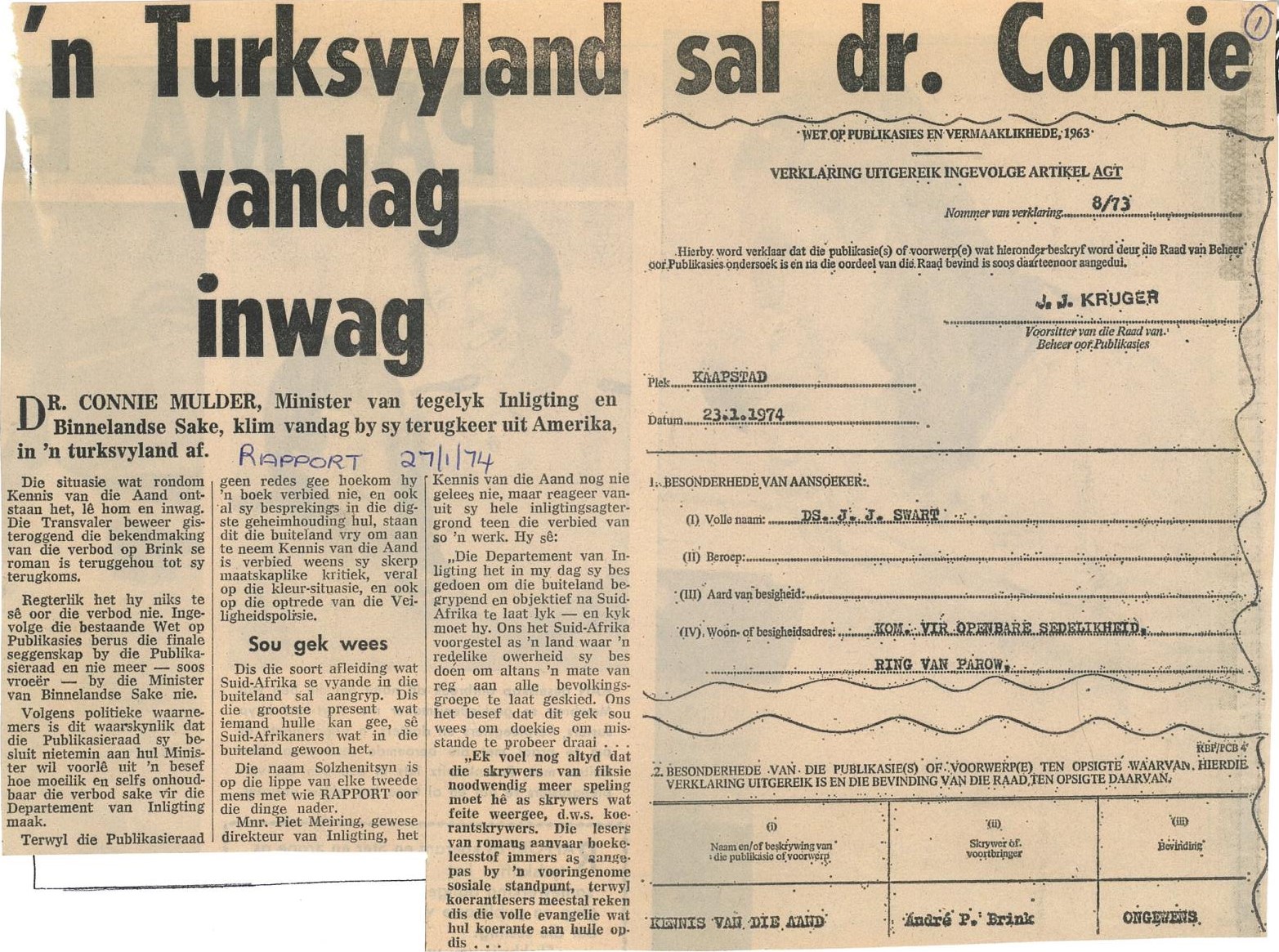

He said there had been no word from the PCB and that was probably because the Old Ladies Who Complain were slow readers and the novel was 500 pages. I probably read slower than those old ladies, but I found the novel impressive and said as much. By then, the beginning of January, he reported that a complaint had been lodged and the novel was being scrutinised by the censors.

It was initially reported in Die Transvaaler that the complainants had been two ladies from Pretoria, a Mrs AA van Wyk and the writer Mrs TC Pienaar. However, Mrs Pienaar — a largely forgotten writer of the plaasroman (farm novel), a genre preoccupied with rural virtues, locusts, droughts and poor whites — later contradicted claims that she’d lodged a complaint. She said she hadn’t read any of Brink’s novels and had no intention of doing so. Nonetheless, she added that if the novel was not banned it would set a dangerous precedent for the country’s morality.

The first print run was sold out, but André and Saayman had to wait for “a verdict from the fucking censors” before they could give the go-ahead to print the second edition. I don’t think he could really have expected a benevolent outcome as he reported that certain sections of the press were having a field day reporting on the novel’s “transgressions against the Volk” and how it was “undermining state security”.

The PCB’s deliberations had been shrouded in secrecy. When no newspapers had been able to get a leak from a board member, André phoned the Chairman of the Board — Jannie Kruger — personally. Kruger told him that the decision didn’t concern him. When André expostulated that he and the publisher stood to lose a lot of money if they printed a second edition and the book was subsequently banned, the great man pronounced: “The only way in which you can officially hear about a decision would be if you lodged a complaint against the book yourself”.

André described this conversation “as pure Kafka with more than a hint of Orwell added to it”. At the time — and he was mindful of the fact that our letters were regularly intercepted and read — he said someone had obtained the information from “a female member of the Board”, but in A Fork in the Road he tells it differently.

He took Kruger at his word, contacted a friend in Johannesburg called Naas and asked if he’d get his secretary to lay a complaint against the novel. This she did and, on Friday 25 January, she was given the confidential reassurance that the novel was going to be banned and that the notice would appear a week later in the Government Gazette. On the same day, André wrote and told me he knew Kennis had been banned and on the Sunday Rapport broke the story.

An article published in Rapport, 27 January 2974. (Image: Amazwi South African Museum of Literature / Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

An article published in Rapport, 27 January 2974. (Image: Amazwi South African Museum of Literature / Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

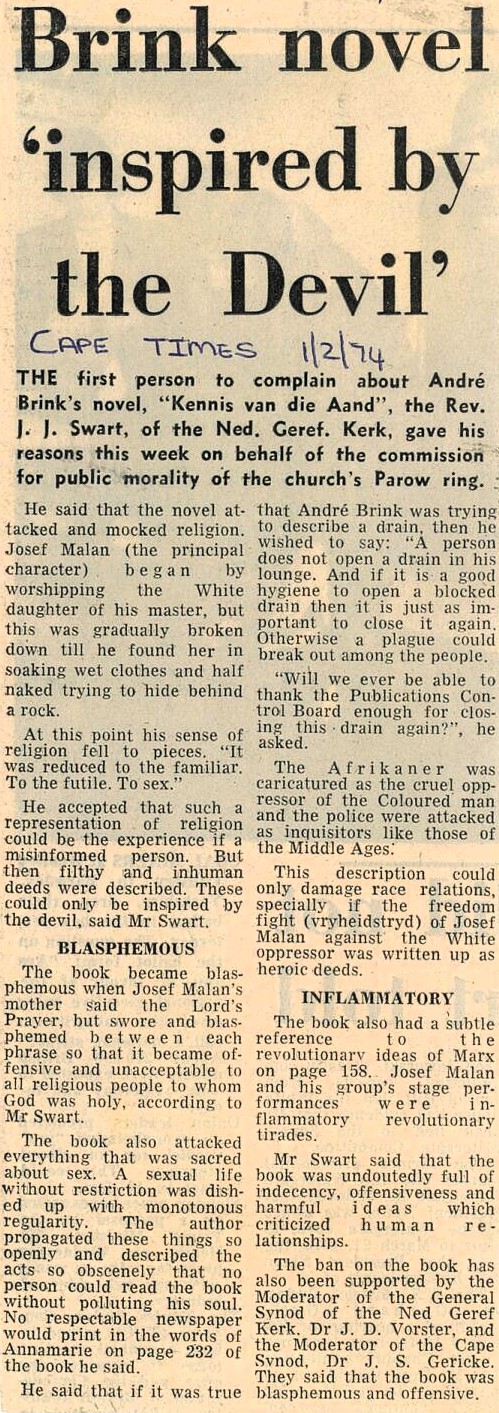

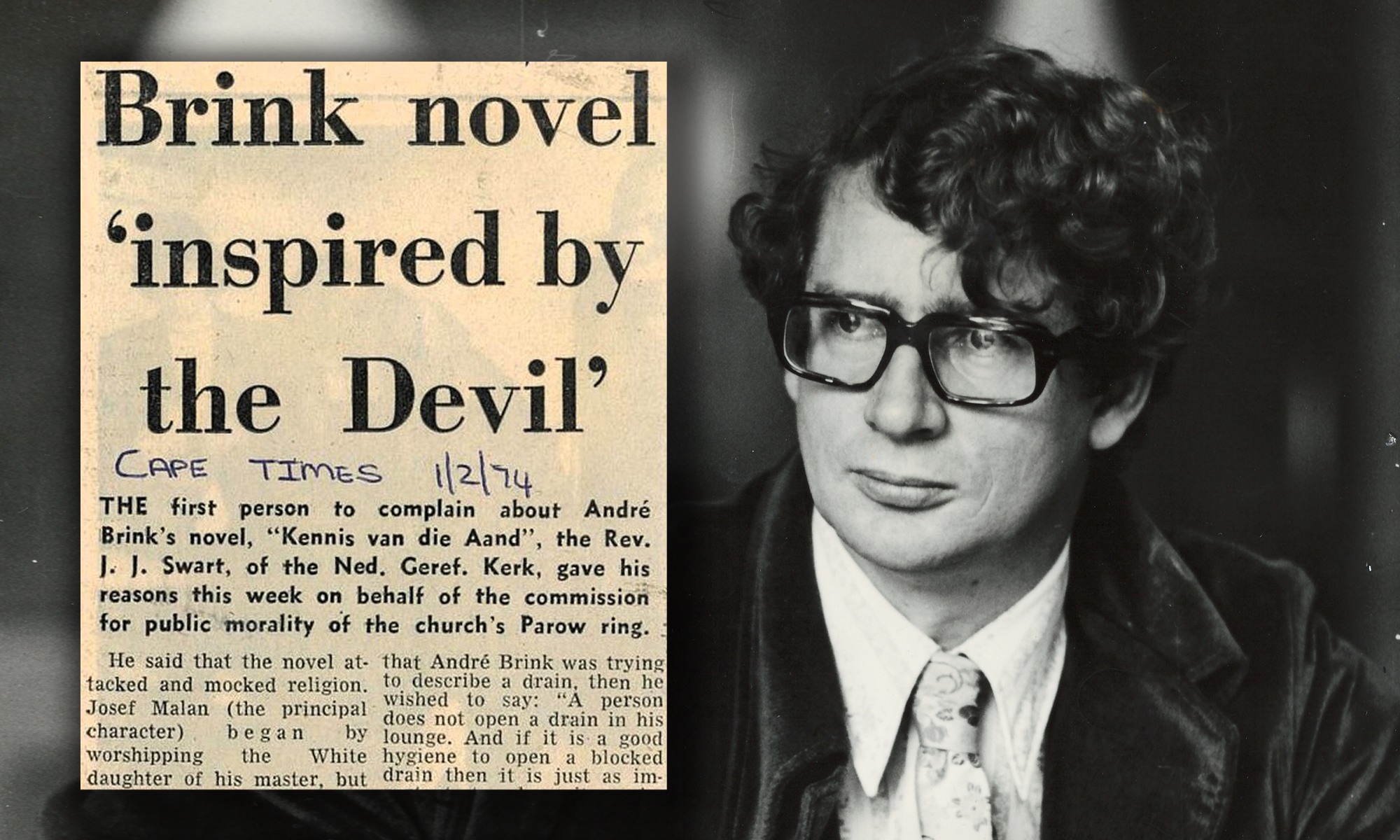

In the event, the complainant credited with succeeding in having the novel suppressed was not Mrs AA van Wyk — there were clearly several complainants — but Dominee JJ Swart of the Parow branch of the Komitee vir Openbare Sedelikheid (Committee on Public Morals).

André and Saayman must have anticipated this outcome and he told me they intended to go to court to appeal against the ban. Saayman had already approached one of the country’s leading advocates (Ernie Grosskopf SC) to appear for them. He expected the matter wouldn’t be heard before July or August and was fairly confident they’d lose in the Cape, but then hoped to take the matter on appeal in Bloemfontein.

If they lost in Bloemfontein, he said, he’d be in debt for the rest of his life. He mentioned that the Afrikaanse Skrywerskring (Afrikaans Writers’ Circle) in the Transvaal had launched a fund to help with their legal expenses. He was profoundly touched by this gesture of solidarity because, he said, many of their members were not well-disposed towards him. He didn’t say who or why.

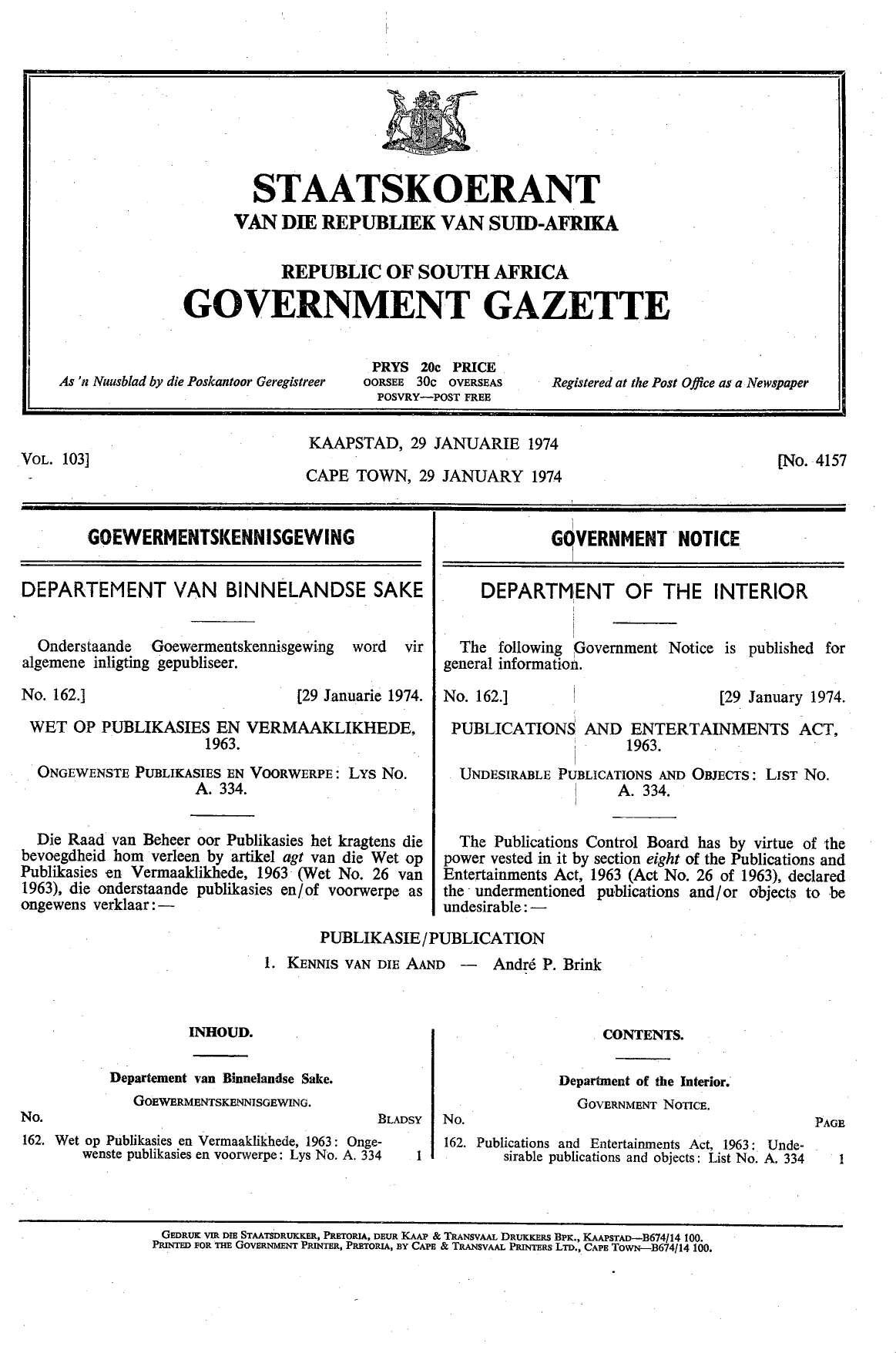

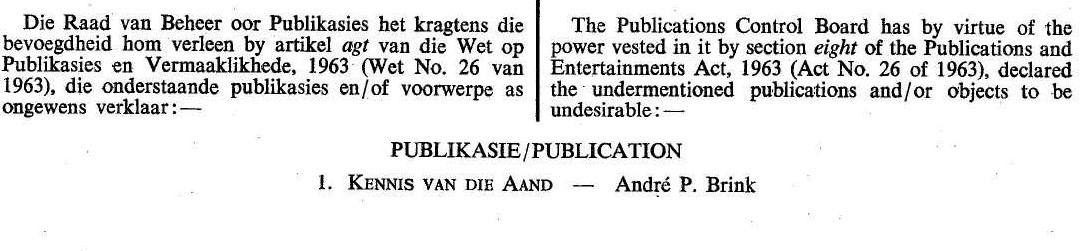

South African 'Government Gazette', dated 29 January 1974, no 4157. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

South African 'Government Gazette', dated 29 January 1974, no 4157. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

South African 'Government Gazette', dated 29 January 1974, no 4157. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

South African 'Government Gazette', dated 29 January 1974, no 4157. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

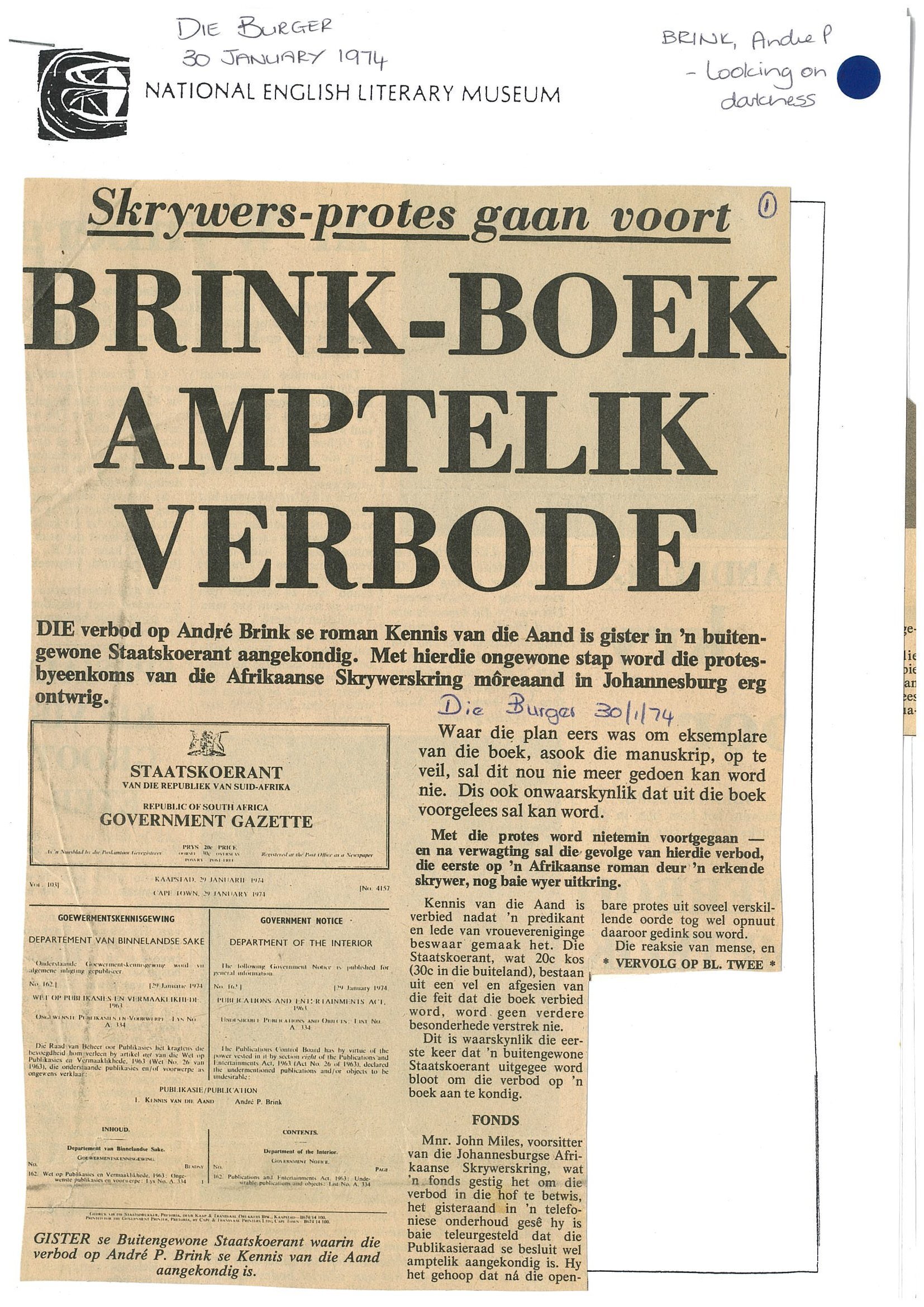

(Image: Amazwi South African Museum of Literature / Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

(Image: Amazwi South African Museum of Literature / Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

An article from Cape Times, 1 February 1974. (Image: Amazwi South African Museum of Literature / Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

An article from Cape Times, 1 February 1974. (Image: Amazwi South African Museum of Literature / Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

Three days later, he wrote and told me he’d begun working on the translation. The ban obviously gave him a sense of urgency and Saayman would have been putting out feelers to overseas publishers. André said he planned to have it done by the end of April. That meant he was going to translate on average five pages a day on top of all his university commitments and the demands of a growing young family.

***

On 7 March, he wrote saying he was halfway through the translation. He was inspired to keep up his pace because he’d received what he described as wonderful offers from publishers abroad — Doubleday and Random House in the United States and WH Allen in Britain. He also mentioned that Saayman had brought the deadline forward by 30 days and had promised these publishing houses the manuscript by the first week of April. That meant André would have to translate at least eight pages a day.

I don’t think it occurred to me at the time that by banning the novel the PCB had raised André’s international profile. Anti-apartheid sentiment was growing in Europe and the US and a novel that had been suppressed by the apartheid regime — especially one by an Afrikaans writer — immediately gave publishers a unique marketing angle. Of course, his novels would stand or fall on their literary merits, but the unintended consequence of Kruger and his henchmen making a pariah of André Brink was that they launched his international career. Kennis van die aand was eventually translated into 33 languages.

André made his insane translation deadline — he’d also have had to revise and correct his translation — and on 17 April he reported that the English rights had been sold to WH Allen and publication had been scheduled for 14 October.

***

The appeal was set down at the Cape Provincial Division of the Supreme Court for 5 – 7 August. Two months earlier the PCB had responded to their affidavits and that response gave André a sinking feeling. The main thrust of their argument had been that Kennis was a novel and not “factual comment”. In their response, the PCB quoted at length from his articles, speeches and lectures to demonstrate that for years he’d been advocating for a literature that would engage with South African reality and expose it for what it was. Although he stood behind what he’d advocated, he said he felt it didn’t give him a leg to stand on.

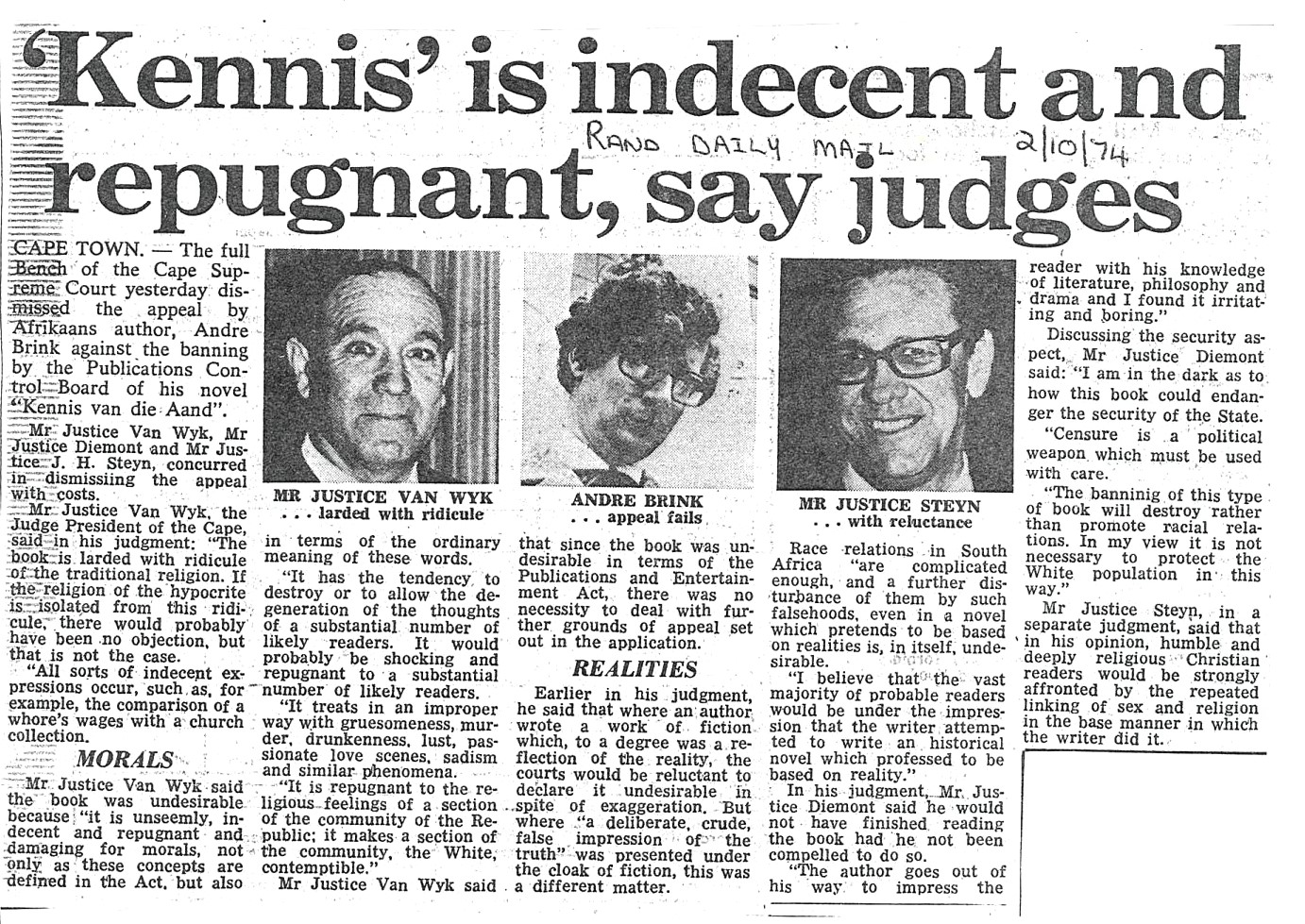

Two weeks after the appeal was heard, André wrote from Gordon’s Bay where he was on holiday with the family. He said that judgment had been reserved and that it could be months before he knew the outcome. The appeal panel had consisted of three judges, one of whom — JT van Wyk — was the Judge-President of the Cape Supreme Court. André said he’d expected Van Wyk to be against them, but everyone was taken aback at the “blatant, abusive, aggressive prejudice from the bench”.

At the outset, he implied that if the defence managed to demonstrate that every reason advanced by the PCB for banning the book was baseless, he’d still find reasons for keeping it banned. He admitted he hardly ever read books, either in Afrikaans or English.

André felt sure they’d hold back the verdict until the new censorship bill had been passed. Doing so would make it impossible to appeal the verdict in Bloemfontein, as the new Act would abolish the right of appeal to the courts. He and Saayman had agreed to go 50-50 on the costs, which by then had already amounted to R13,000 (approximately R800,000 today), and that morning he’d heard that the Skrywerskring fund hadn’t yet raised R5,000.

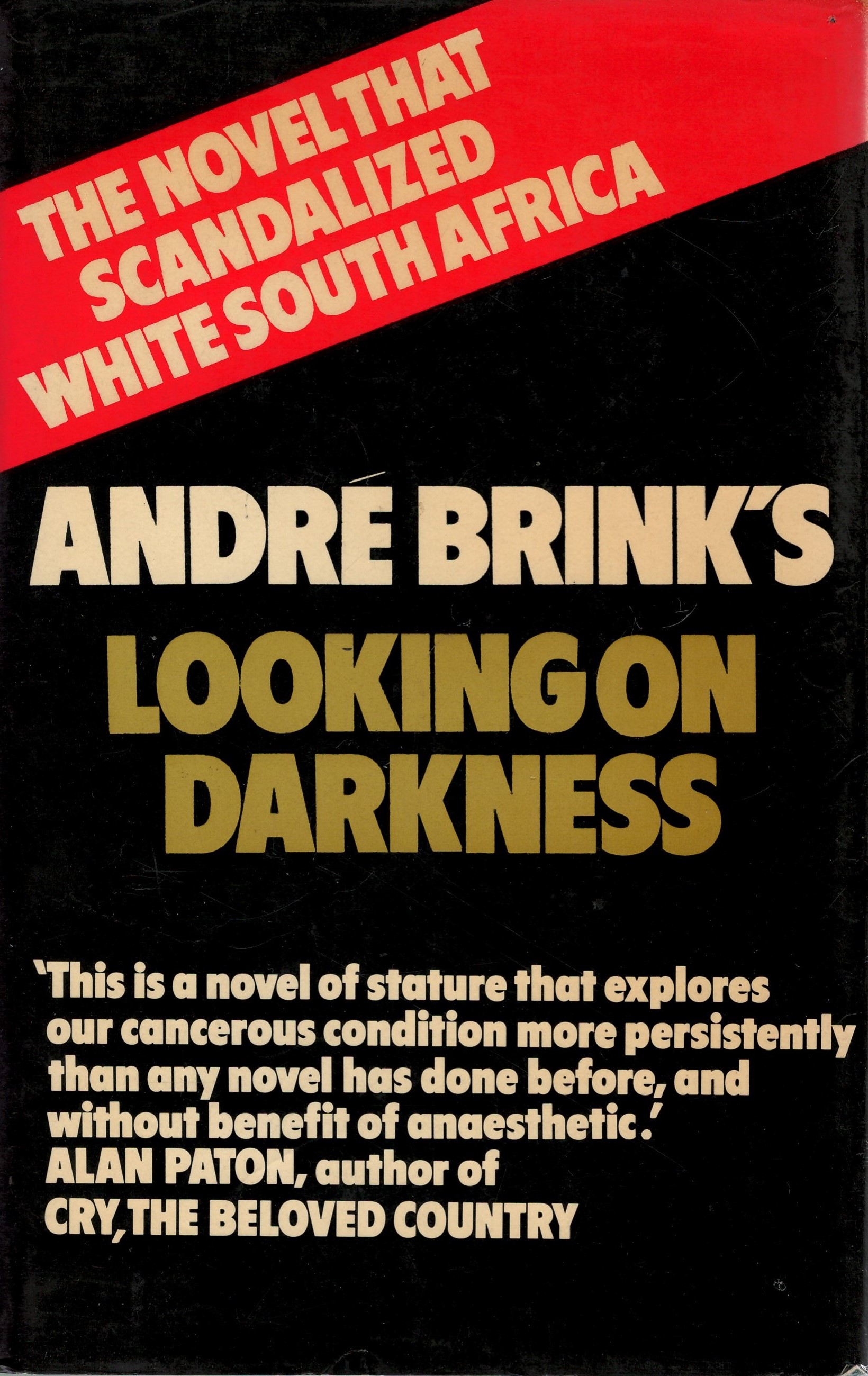

The appeal against the banning of Kennis was dismissed on 1 October. Two weeks later his translation entitled Looking on Darkness was published in London and he received the news that the American rights had been sold for "an astronomic sum" ($30,000 — i.e., $187,000 today, although at the time $1 only bought 67 South African cents). He said that advance would cover all their legal costs with some to spare. He fully reimbursed the Transvaal Writers’ Fund.

An article in Rand Daily Mail, 2 October 1974. (Image: Amazwi South African Museum of Literature / Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

An article in Rand Daily Mail, 2 October 1974. (Image: Amazwi South African Museum of Literature / Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

On Saturday 23 November, we met up in London and, over a meal, André told me about a new novel he planned to write. It was a story of a runaway slave and a white woman in 1750, who fall in love and escape into the hinterland. On the same day, he gave me an inscribed copy of Looking on Darkness.

‘Looking on Darkness’, published by WH Allen. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

‘Looking on Darkness’, published by WH Allen. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

The following day, Rapport carried a story of how customs officials at Cape Town harbour had seized a shipment of Looking on Darkness and then referred it to the PCB. By the time André got home, it was also banned.

***

On 11 February 1975, he wrote and told me he’d started writing the new novel. I’m not sure if he’d mentioned the title in London, but it was Oomblik in die wind. Once again, he worked at a prodigious pace. By 1 May, he said he was polishing the manuscript after getting very positive feedback on his first draft.

But the publisher — Human & Rousseau — had expressed a concern that this novel would also be banned. He didn’t explain why he’d gone back to Human & Rousseau, but in August he told me Saayman was going out of business and selling his stock to Tafelberg.

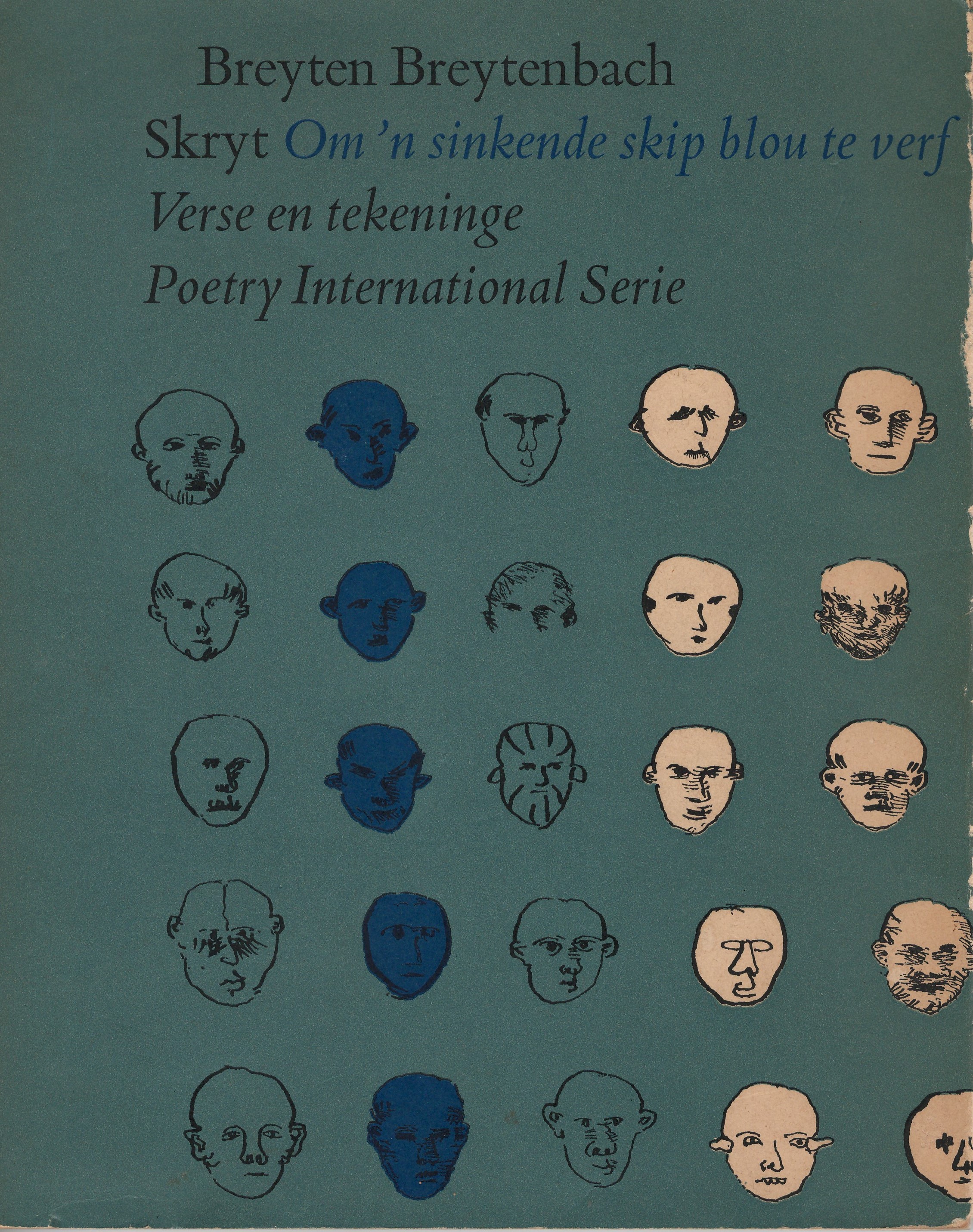

In 1972, Meulenhoff in Amsterdam published Breyten Breytenbach’s Skryt in the Poetry International Series. It’s doubtful if the volume was ever on sale in South Africa, but Prime Minister BJ Vorster took exception to a poem directed at him entitled Brief uit die vreemde aan slagter and, three years after it was published, it became the second literary work in Afrikaans to be banned.

‘Skryt’ by Breyten Breytenbach – the second banned Afrikaans literary work. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

‘Skryt’ by Breyten Breytenbach – the second banned Afrikaans literary work. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

André felt it was part of a strategy to intimidate writers and had become even more pessimistic about the prospects for his new novel after he received a final report from Human & Rousseau saying they thought it was his best novel to date, but they also believed it would definitely be banned. Of course, WH Allen had already agreed to publish the translation but, as he wrote despairingly, “Why the fuck does one write a thing in Afrikaans?”

In July of that year, he was in Johannesburg for a meeting in Broederstroom that led to the formation of the Afrikaanse Skrywersgilde (Afrikaans Writers’ Guild). He said the threat of censorship meant no publisher would risk publishing Breytenbach’s ’n Seisoen in die Paradys. He mentioned the possibility of circulating his book underground and said this possibility was discussed discreetly among the writers. It had to be discreet because 8 Special Branch men were lurking around the periphery at Broederstroom. At the risk of sounding melodramatic, he said, “Afrikaans literature is now battling for its very survival”.

André offered to appeal against the banning of Skryt on Breytenbach’s behalf because the poet was in Paris. Or so André thought. Breytenbach was, in fact, already in South Africa on a clandestine mission and, although he hadn’t contacted André, it later transpired that André’s name was on the list of people he was planning to contact.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Breyten Breytenbach — Prisoner of consciousness, my hero

André’s appeal would be directed to the PCB’s newly established Appeal Board, which was presided over by the arch-reactionary Justice Lammie Snyman. (André later commented that Sny-man was the perfect name for a censor.) Shortly after his appointment, he made his position clear with the following words: “I have never been a great reader of fiction before, but I suppose I’ll have to read many more novels now — fortunately not for cultural reasons”.

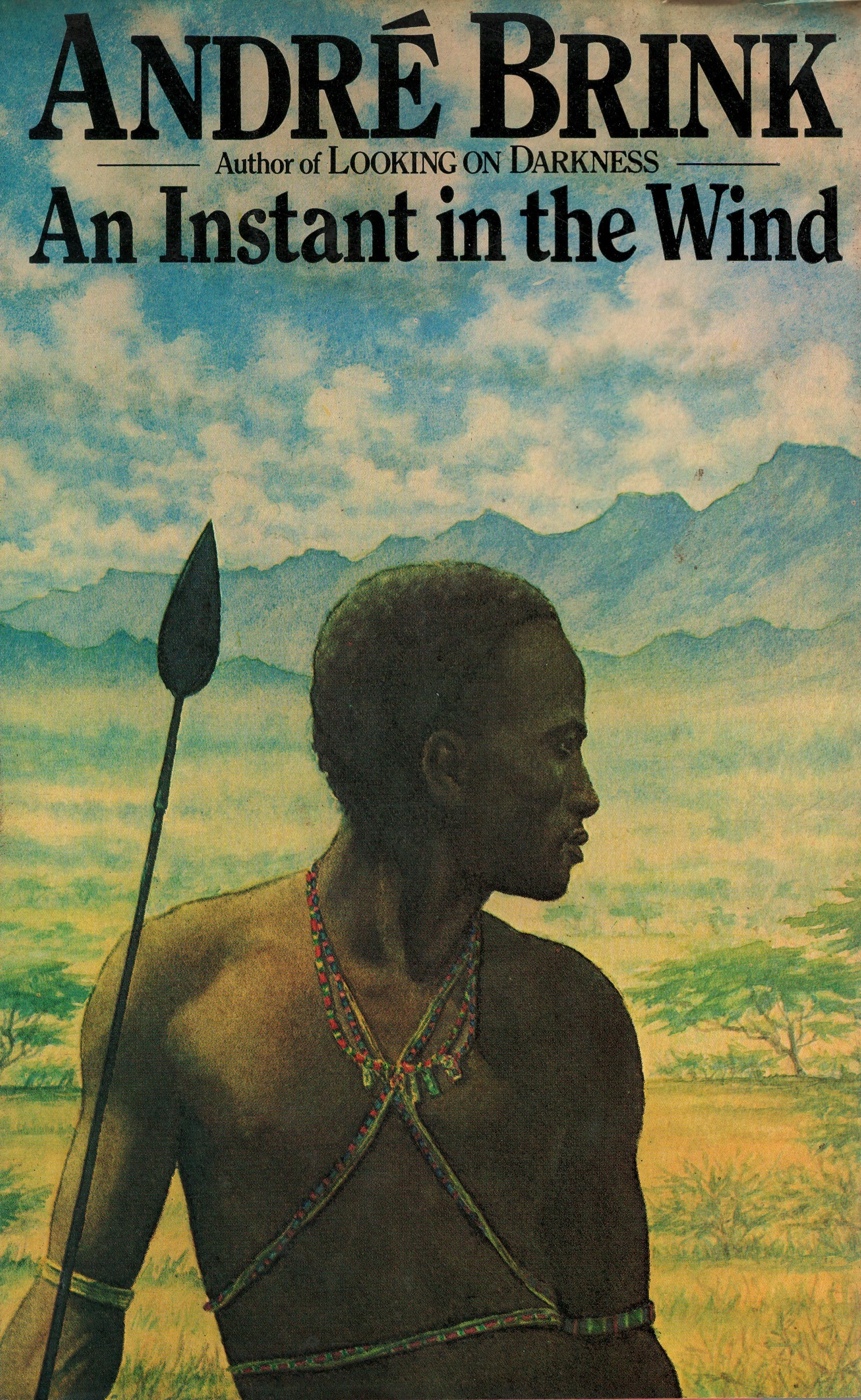

During the preceding months — I’m not sure exactly when — he’d found the time to translate Oomblik as An Instant in the Wind and WH Allen had agreed to publish and had given him a generous advance. Additional legal advice had been sought on the Afrikaans text and it was looking increasingly likely that Human & Rousseau was not going to take the risk. When the final decision came in September, they did issue a statement saying they thought it was his best book.

‘An Instant in the Wind’, published by WH Allen. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

‘An Instant in the Wind’, published by WH Allen. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

Although being published internationally was some consolation, André felt he was being made irrelevant by not being able to communicate directly with the readers he was primarily addressing and being able to do so in their language. And, of course, there was already the precedent of an English translation being seized by customs and subsequently banned.

***

While André was preparing the Skryt appeal, he had no idea Breytenbach had already been arrested at Jan Smuts Airport on 22 August. Like Breytenbach’s parents, he first heard the story on SABC radio news on 2 September.

Uncertainty and speculation surrounded Breytenbach’s arrest but, at the time, there was little André could do for him besides focus on the appeal. He knew he didn’t have a snowball’s chance in hell of succeeding, so he didn’t need to play for the judge’s sympathies and could tell it like he saw it at the risk of being held in contempt of court.

On the day André arrived in Pretoria to argue his case to the Publications Appeal Board, the public prosecutor — the egregious Percy Yutar — said the appeal could no longer proceed because the offending poems were being used as evidence against Breytenbach in his trial and were therefore sub judice. As André remarked bitterly, for the previous two weeks Transvaal newspapers had been running front-page stories about the upcoming appeal. Yutar would have been fully aware of it, but obviously wanted to cause the maximum inconvenience. All André could do was ask the court to record his indignation at the way the matter had been handled.

Breytenbach appeared in the Pretoria Supreme Court on charges under the Terrorism Act and, on 26 November 1975, was sentenced to nine years in prison.

***

On 3 October he’d hinted that there were some publishing possibilities for Oomblik. Rapport newspaper had offered to publish excerpts, but he didn’t think the novel lent itself to fragmentation. He said he’d reconsider if there were no other options, but he was feeling upbeat. He said he couldn’t write about it in a letter, but said exciting things were underway.

Meanwhile, he admitted, the prepublication ban of Oomblik had hit him harder than he’d anticipated. He’d wanted to start work on a new novel, a novel he felt had to be written in Afrikaans, but the thought that that would also be banned made it difficult for him to get started.

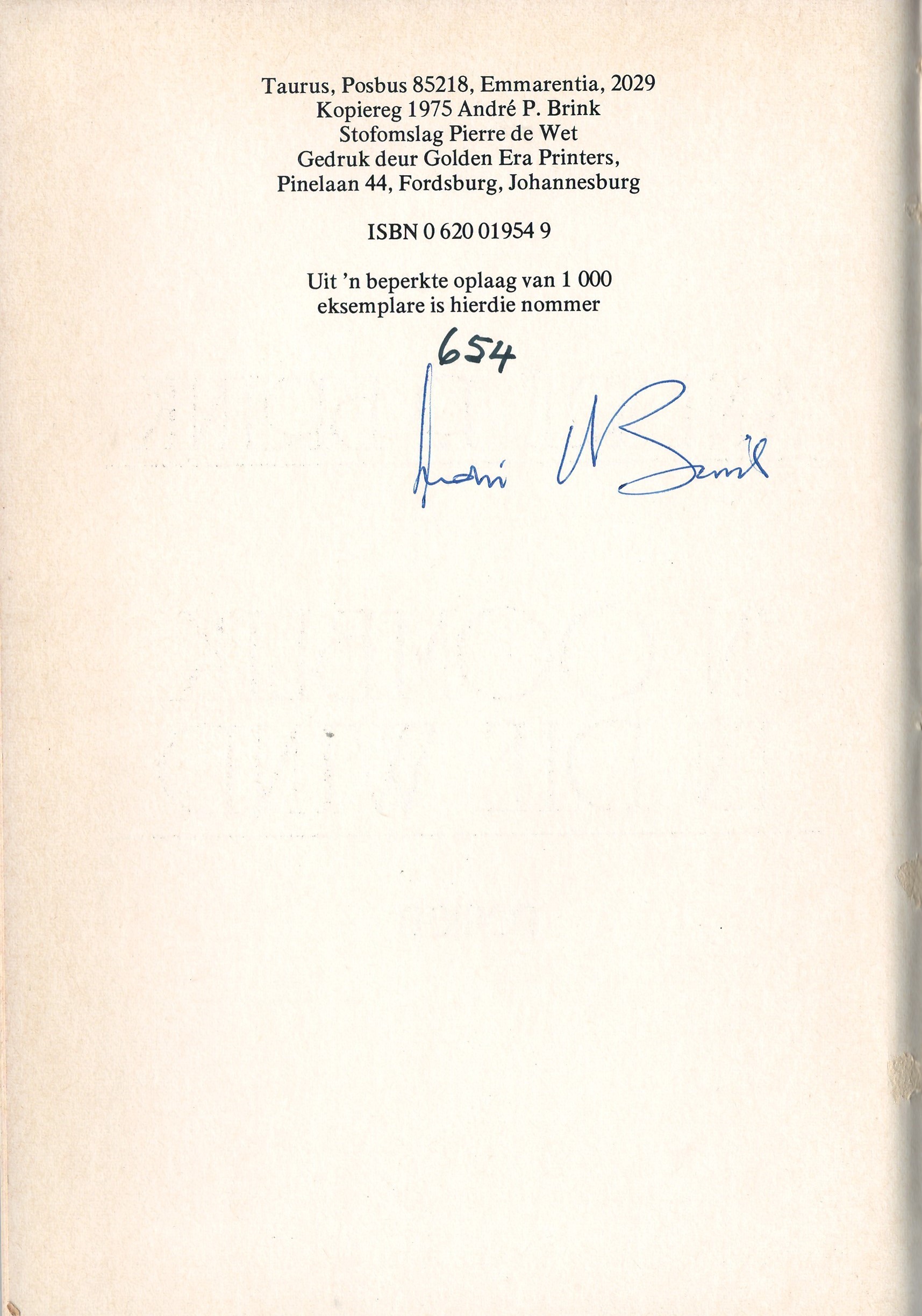

On 7 January 1976, he wrote and told me Oomblik had been published. What seems to have initially been conceived as a self-publishing venture, was taken over by a group of friends — Ampie Coetzee, Ernst Lindenberg and John Miles — who established Taurus. Rapport advertised private subscriptions for a numbered, signed edition and by the time the printers delivered the print run of 1,000 copies they’d all been sold and were posted off to subscribers. The book made a profit of R2,500 (i.e., R150,000) and most of that was used to defray the costs of Breytenbach’s trial.

‘Oomblik’, signed and numbered. (Photo: Anthony Akerman)

‘Oomblik’, signed and numbered. (Photo: Anthony Akerman)

What was most uplifting for André, he wrote, was that the Afrikaans edition of the book had been given a life. However, he was hoping to publish a larger second edition and said they were waiting to hear whether it had got past the censors. He didn’t say how they were doing that, but this is what happened.

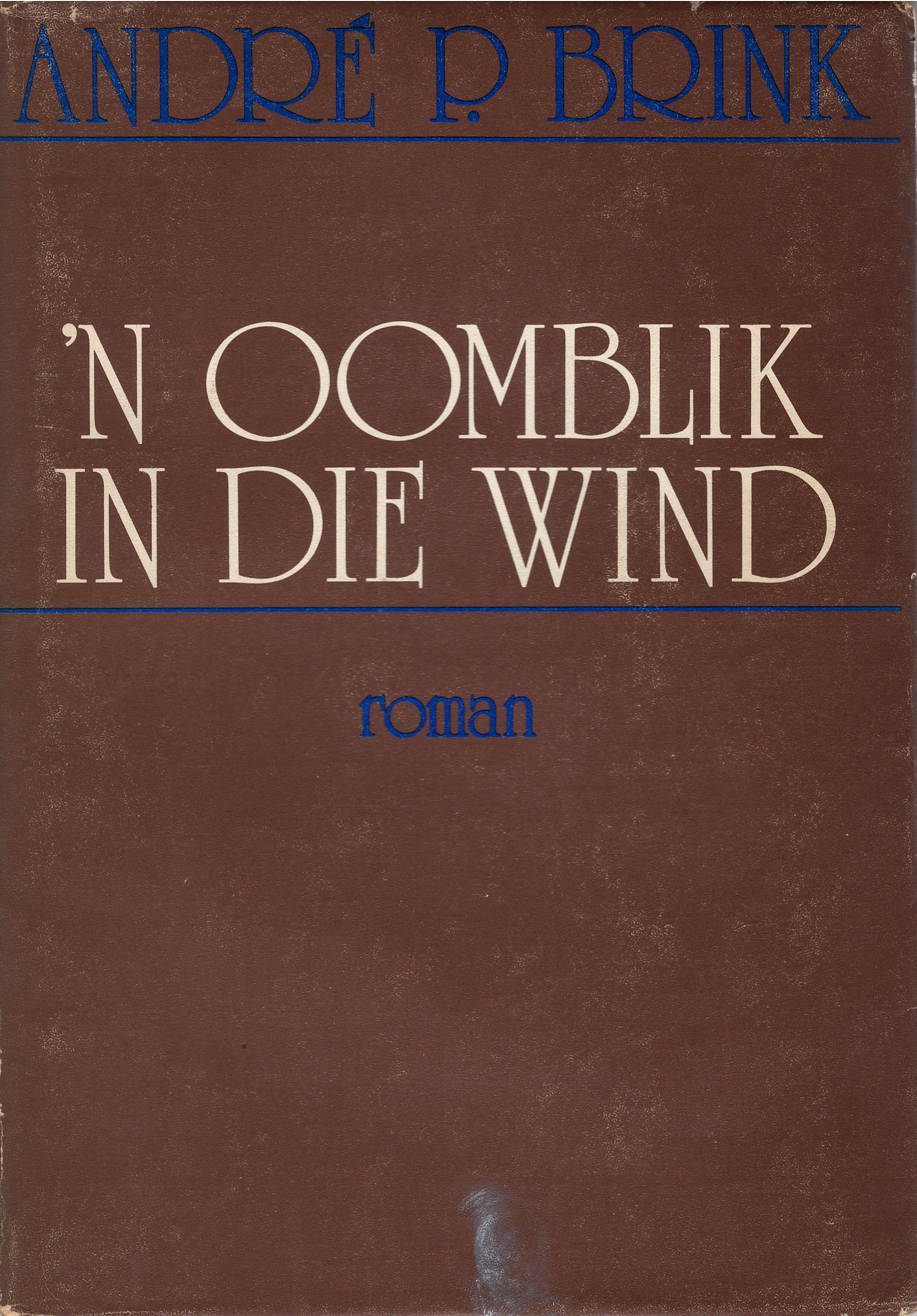

‘Oomblik’, 1st edition, published by Taurus. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

‘Oomblik’, 1st edition, published by Taurus. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

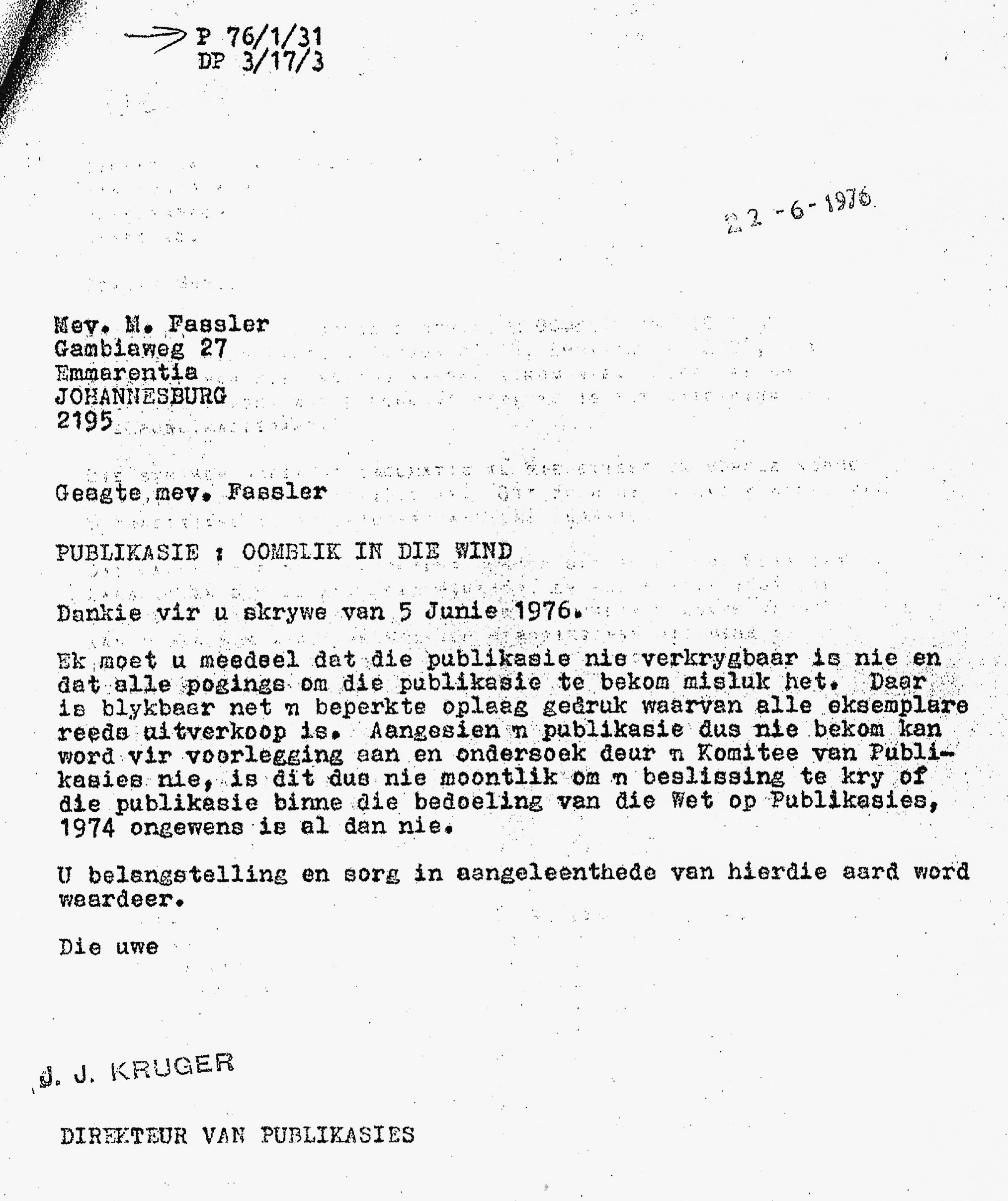

On 5 June 1976, the PCB received an indignant letter from a resident of Emmarentia in Johannesburg enquiring whether this novel — “a deliberate provocation to the PCB” — had been banned. In it, she went on to say the author attacked all the ethical and moral norms of the Afrikaner-Calvinist. In his reply, Mr Kruger said he valued her concern, but regretted to inform her that they’d not been able to get hold of a copy of the novel and were therefore not in a position to declare it undesirable. The complainant was Marianne Fassler. Yes, that Marianne Fassler who was, at the time, one of Ampie Coetzee’s star students and had written a letter to get the clarification they needed.

JJ Kruger to Marianne Fassler, June 1976. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

JJ Kruger to Marianne Fassler, June 1976. (Image: Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

This cleared the way to go ahead with the paperback edition and by August, the Ad Donker edition of Oomblik was in bookshops. André wrote that he hoped the profits could be “ploughed into publishing further titles endangered by censorship”. As soon as the paperback edition appeared, Die Vaderland ran a front-page story speculating on the likelihood of the novel being banned and the unintended consequence was that 3,000 of the 4,000 printed were sold in a week.

In October, this edition was examined by the committee of the PCB and found to be "not undesirable". Just to add salt to the PCB’s wounds, the English translation was shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

He may have outwitted the authorities, but they were unforgiving and he became the victim of a smear campaign in the press. In December, Die Vaderland published a leader in which the editor asked BJ Vorster to give the volk a Christmas present in the form of "André Brink se kop op ’n skinkbord" (André Brink’s head on a plate).

***

Although Skryt remained banned, the incarcerated Breytenbach’s ’n Seisoen in die paradys was published in 1976. A complaint was lodged against the book by Detective Sergeant JC Engelbrecht, but in February the following year the PCB decided not to ban it as that would “serve no purpose”. Etienne Leroux was not so lucky that year when Magersfontein, O Magersfontein! became the next Afrikaans literary work to be banned. The publisher appealed, but the ban was upheld by the Publications Appeal Board. The following year, John Miles’s satiric (blasphemous) novel Donderdag of Woensdag — published by Taurus — was also banned.

André’s ’n Droë wit seisoen was published by Taurus in August and in English as A Dry White Season by WH Allen in September 1979. In a letter on 2 November that year, he wrote, “With the ban on Gordimer’s latest book lifted very unexpectedly there is a slight chance of the reversal of the ban on mine too”.

He was referring to Burger’s Daughter and the ban on his own A Dry White Season, which had been banned on 9 September. Gordimer’s novel was banned on 11 July and — presumably, in part at least, because of the international outcry against the banning — on 1 August the Director of Publications appealed against his own censorship committee’s decision and the novel was subsequently unbanned.

The same procedure was followed with André’s A Dry White Season. The Directorate of Publications appealed against the decision taken by its own Committee of Publications on 21 September and on 11 November the appeal successfully set aside the ruling, unbanning the novel in both English and Afrikaans.

Both Gordimer and André were aware that this "special treatment" accorded to them would not be applied equally across the board and that nothing would have changed for less well-known black writers.

In 1980, Professor Kobus van Rooyen replaced Justice Lammie Snyman as chairman of the Publications Appeal Board and, when the publisher again appealed against the banning, Magersfontein, O Magersfontein! was unbanned.

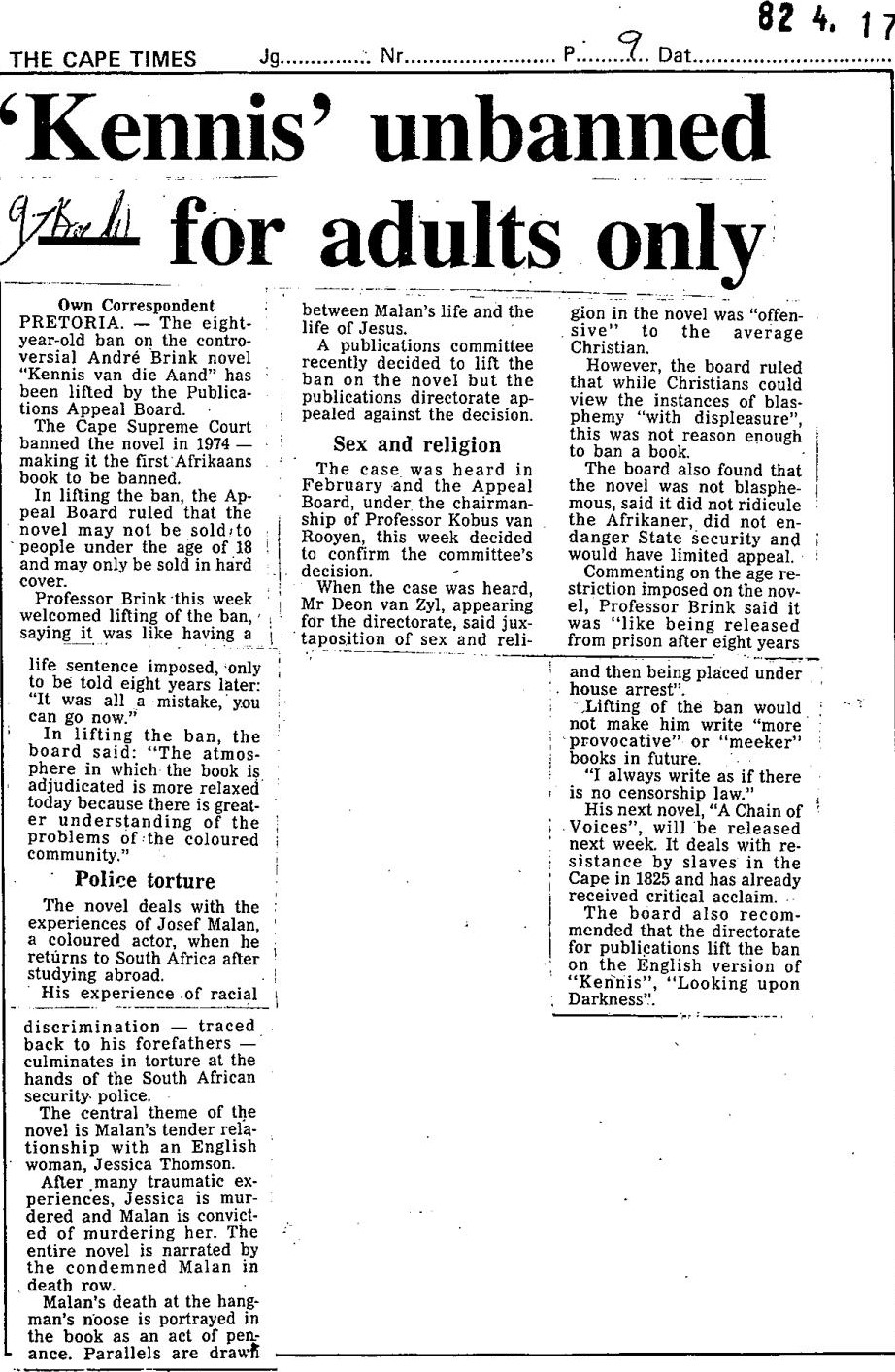

In November 1981, a committee of the PCB deliberated on Kennis, subsequent to a successful lifting of the ban on the English translation in 1980. After much convoluted discussion, they concluded that the novel was no longer undesirable. However, it was only on 17 April 1982 that The Cape Times ran the headline: “‘Kennis’ unbanned for adults only”.

From The Cape Times. (Image: Amazwi South African Museum of Literature / Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

From The Cape Times. (Image: Amazwi South African Museum of Literature / Supplied by Anthony Akerman)

Kennis van die aand was unbanned, although with terms and conditions: only hardcover editions could be sold and — although clearly problematic to enforce — no one under the age of 18 was allowed to read it. Presumably, once you were old enough to vote, drive a car and drink alcohol, you were resilient enough to withstand the novel’s onslaught on your worldview and moral fibre. DM

From The Cape Times - 'Kennis unbanned for adults only'. (Image: Anthony Akerman)

From The Cape Times - 'Kennis unbanned for adults only'. (Image: Anthony Akerman)